I had way too much fun at the traveling Museum of Failure pop-up, which is currently in Washington, D.C. until November 30. It's exactly what it sounds like: a monument to all the seemingly good ideas humans have had over the years that for one reason or another failed spectacularly. There wasn't too much information readily available – that required downloading the museum's app – and at times the scant label copy was presented far too flippantly for inventions that seriously injured or even killed people. Then there were the "inspirational" quotes from less than savory characters and a disproportionate amount of space devoted to debating whether Elon Musk is a genius (spoiler: he's not. But he is a fascist.) Despite these critiques I enjoyed the show. Plus, it inspired me to briefly discuss some of the biggest makeup fails of the modern era. While there are tons of failures across all beauty categories such as skincare, haircare, fragrance, bath and body products, etc., literally thousands of defunct brands, and a history of toxic ingredients that goes back to antiquity, I narrowed it down to just a handful of what I think are the most notable modern cosmetic fails. Here's the makeup edition of the Museum of Failure!

Kurlash Eyelash Curler

ca. 1923

It's fairly obvious why the first patented eyelash curler did not stick around long. Known as the "bear trap," Kurlash's instrument does not resemble anything one would want to get near their eyes. While it's actually not dangerous per se, as Lucy Jane Santos notes, the lack of cushioning meant an increased risk of tearing out the lashes, or at the very least resulted in a sharp right angle to the lashes instead of a soft upward curve. A new model was produced less than a year after the initial design and became the standard.

For more on Kurlash, also check out Cosmetics & Skin's excellent history.

Drug Detecting Nail Polish

2014-2018

In 2014 a group of 4 students from North Carolina State University proposed a nail polish that would change color upon detecting date rape drugs such as rohypnol in beverages. I'm not even sure where to start in terms of the many points on which this idea failed. The technology wasn't even available, yet the polish, named Undercover Colors, was touted as something that was ready to be put into production. It wasn't until 2018 the group ceded that the technology would not be available any time soon and presented instead the Sip Chip, a coin-sized disk that can detect certain drugs with 99.93% accuracy with just a couple drops of liquid. Still, the myth of the polish persists. Perhaps the biggest misstep is that, as usual, it placed the burden of prevention on the would-be victim. As a sort of epilogue to Undercover Colors, in 2022 a company named Esoes (pronounced S.O.S.) announced a drug detecting lipstick. Clearly undaunted by the backlash surrounding Undercover Colors, the company forged ahead with a liquid lipstick containing drug test strips hidden in the cap and equipped with a Bluetooth connection to call 911. Sigh.

(image from esoescosmetics.com)

Glamour Lips Lipstick Applicator

ca. 1940-50s

As we'll see later, lipstick, like mascara, is a fairly straightforward cosmetic to apply. A contraption like this applicator is exceedingly unnecessary and only complicates things. Users were instructed to put a coat of lipstick to the applicator – I'm guessing that was a rather messy process – and then press the applicator to the lips for a perfectly defined pout. I can't locate the one in the Museum's collection at the moment so here are photos from one on Etsy.

(images from etsy.com)

It's baffling that this company believed it could hoodwink women into thinking smearing lipstick on a piece of metal first was somehow easier than applying straight from the tube, or even using a lip pencil to line and/or a brush, especially as both lip pencils and brushes were readily available at the time. Heck, Tussy offered a product called the Stylip, a pen-like device which was obviously much less cumbersome to use. Then again, there is nothing businesses won't do if they think it'll make money.

Honorable mention: this (presumably) earlier version, which worked similarly.

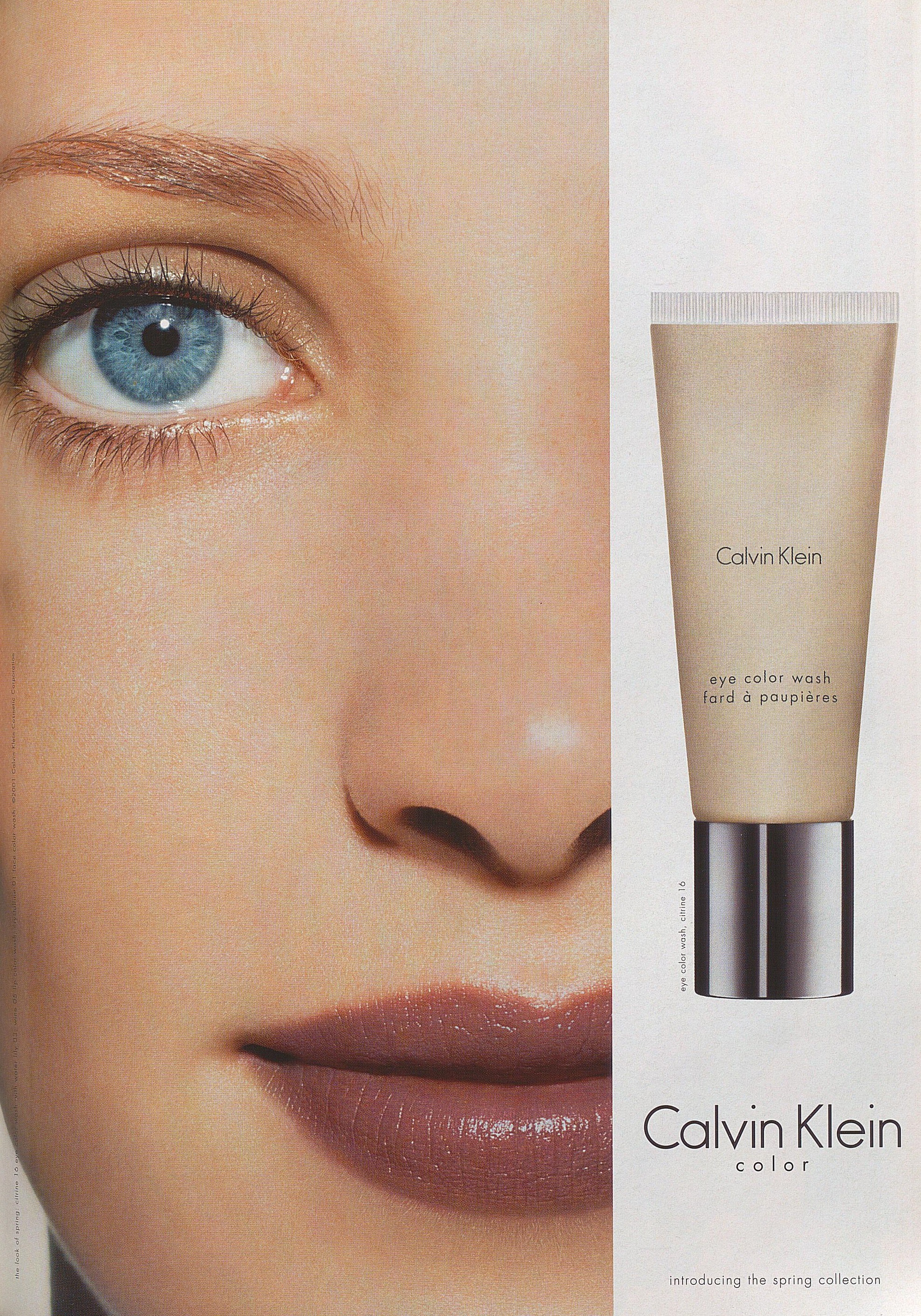

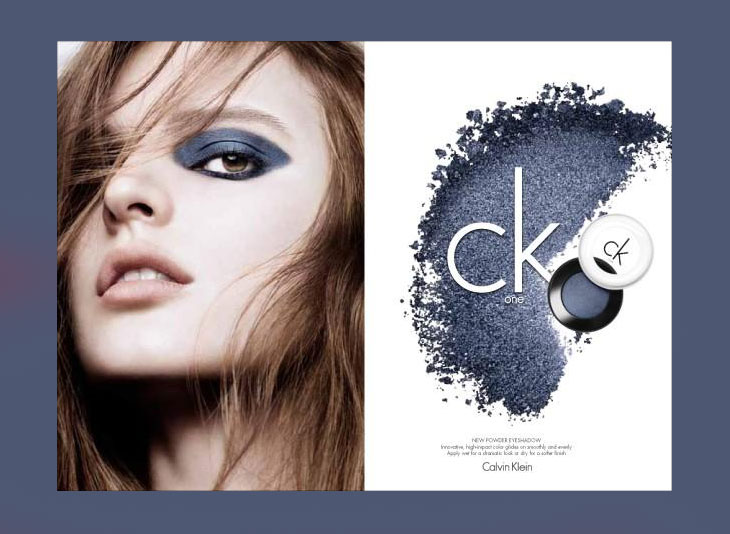

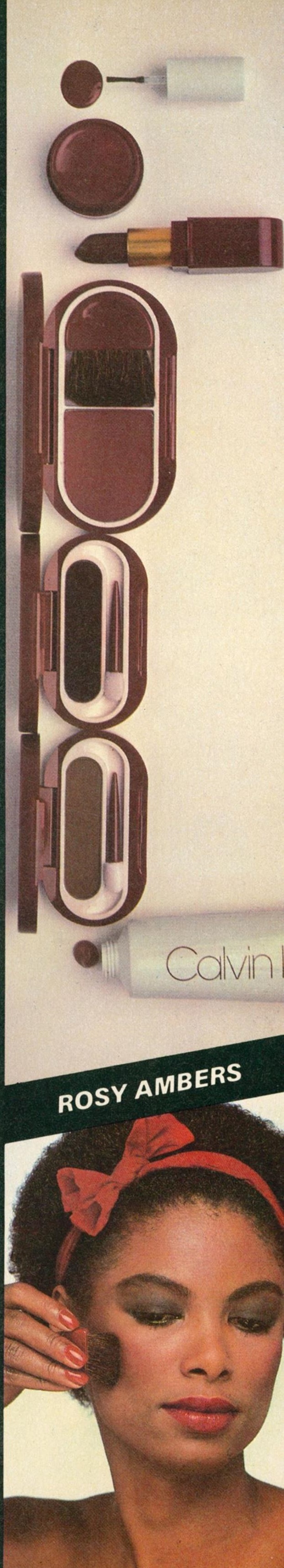

Calvin Klein Cosmetics

1978-1985

2000-2003

2007-2009(?)

2012-2015(?)

Since the 1920s, nearly every fashion house expands into beauty at some point as a relatively low-effort additional revenue stream. While most fashion designers are able to maintain their grip on fragrances, many struggle to keep a color cosmetics line afloat. The popularity of both fashion and celebrity-fronted makeup lines exploded in the '70s and '80s and many of them, including Halston, Diane von Furstenberg and Ralph Lauren, did not survive. However, I want to highlight Calvin Klein cosmetics, whose failure is interesting because the company tried not once, not twice, not thrice, but FOUR times to sell a color cosmetics line.

(image from cosmostore.org)

(images from designscene.net)

It's a long and muddled saga for which I hope to give the details someday, but in a nutshell, it seems the repeated failures were largely due to poor management rather than bad products. The cosmetics arm was sold numerous times and had a revolving door of executives. Without stable leadership and a clear, consistent vision for marketing and distribution, it's virtually impossible for any brand to last. Maybe 5th time's the charm?

Lash Lure Eyelash and Eyebrow Dye

1933-1934

The story of Lash Lure is a rather gory one so consider yourself warned. In 1933 a company named the Cosmetic Manufacturing Co. released an lash and brow dye that contained paraphenylenediamine (PPD), a chemical that can cause acute allergic reactions when used around the eyes due to the skin being thinner in those areas. Between 1933 and 1934 the Journal of the American Medical Association reported the cases of 5 women who went blind after using Lash Lure and one more who developed abscesses after using the product, contracted a severe bacterial infection and subsequently died. In 1938 the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act was finally passed, and the first product it removed from shelves was Lash Lure.

(image from the FDA on Flickr)

The FDA prohibited PPD from being used in cosmetics in the U.S., but it's still widely used in hair dyes; however, the risk of death is considerably lower than in the '30s. The scalp is thicker than the skin around the eyes and less prone to irritation, and if severe reactions like abscesses and infections did occur, there are treatments available. In the early 1930s allergy remedies and most antibiotics hadn't been invented. Having said that, PPD is derived from coal tar, which doesn't seem like a good thing to put near one's eyes in any case.

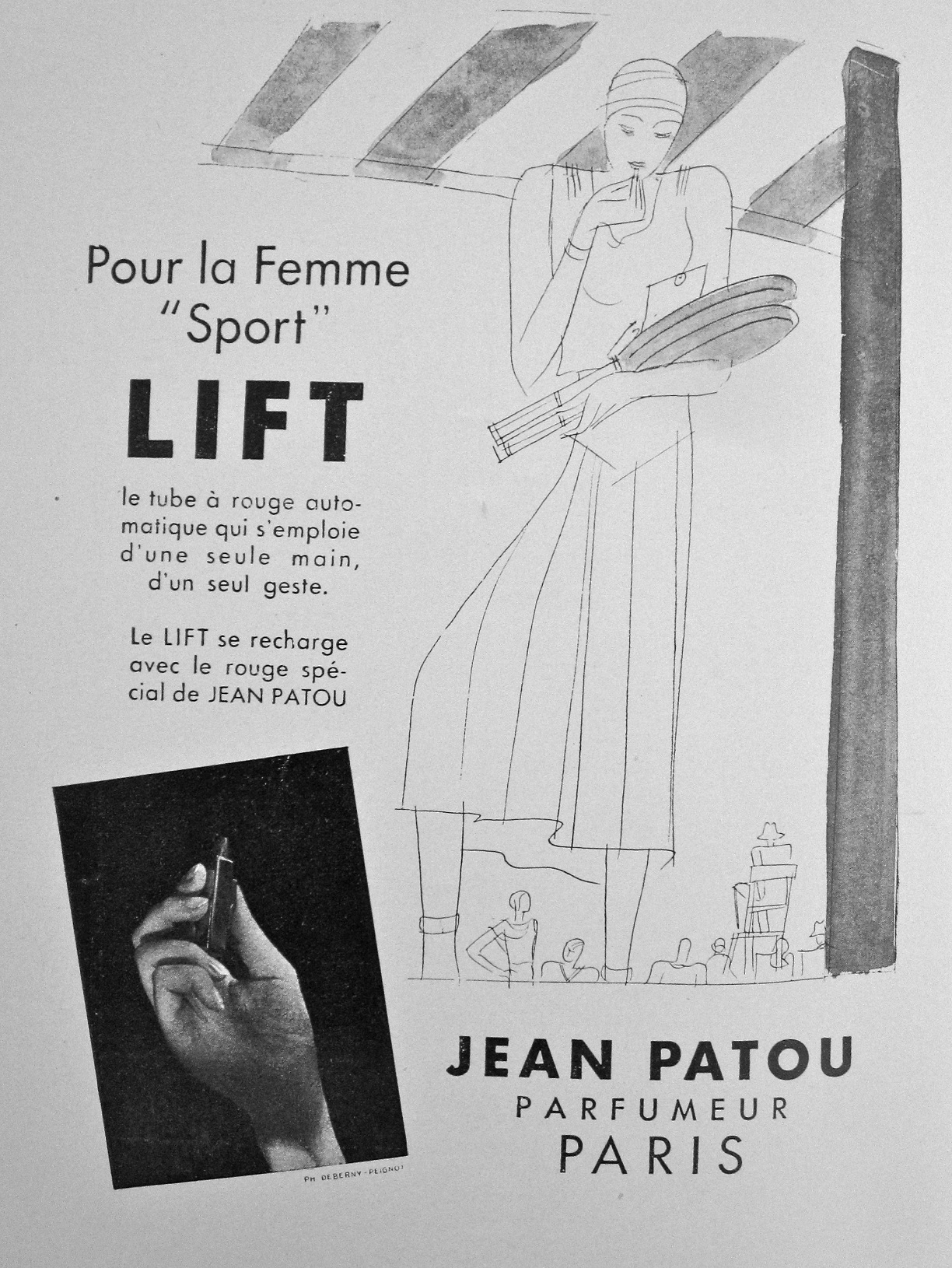

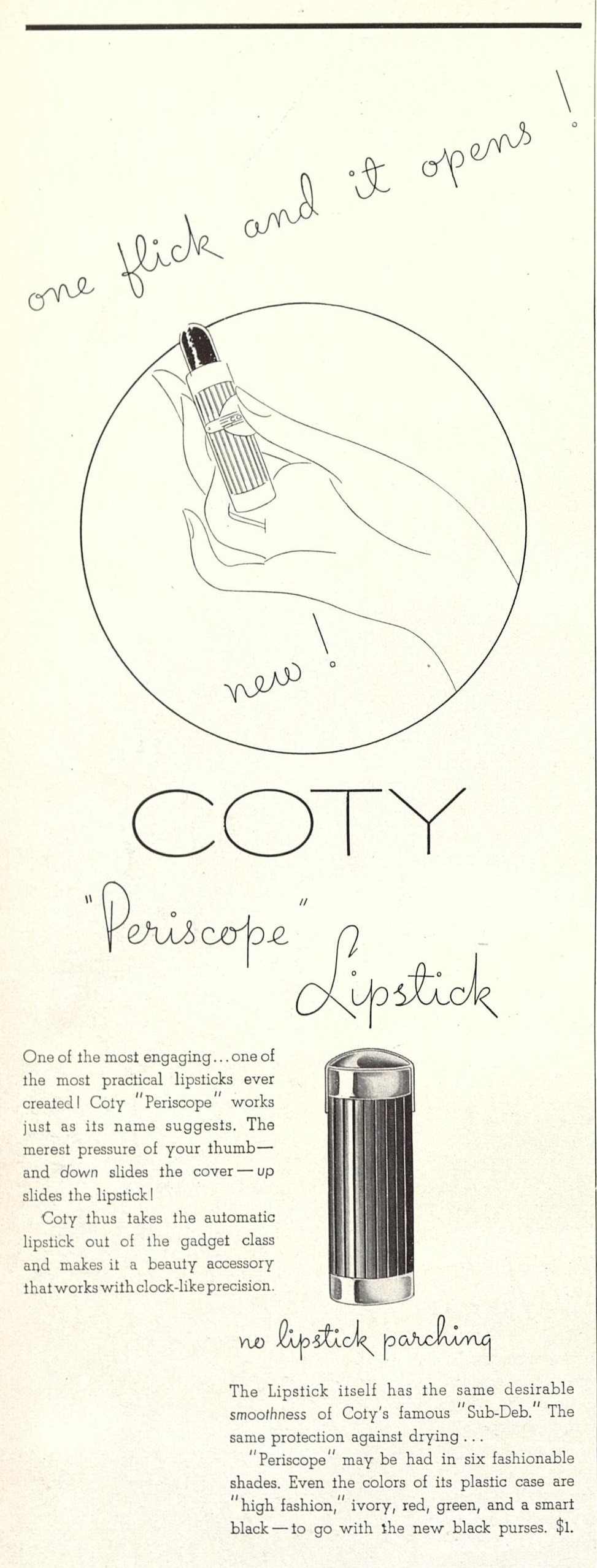

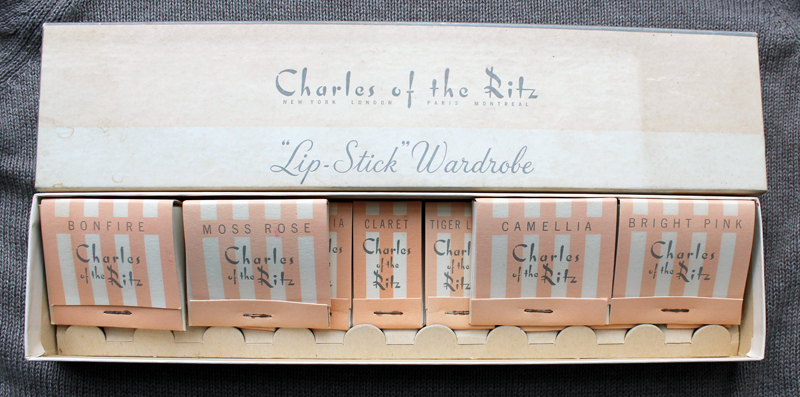

Automatic Lipsticks

1930s-2015(?)

In doing the research for the presentation I made for the Art Deco Society UK back in March of this year, I came across many fascinating so-called "automatic" lipsticks. They expressed the design proclivities of the time in that they were intended to be streamlined, cutting-edge devices that only took a fraction of a second to open for the busy modern woman. No need to use both hands turning a slow-moving swivel tube or one with a traditional cap – the new automatic lipstick was here to save the day!

I was hoping to get to an in-depth discussion of automatic lipsticks for National Lipstick Day back in July, but obviously that didn't happen. Maybe in 2024.

Anyway, I think there's a reason the swivel remains the most common lipstick mechanism. This is purely anecdotal based on the automatic lipsticks I've added to the Makeup Museum's collection, but they tend to get stuck easily. I noticed that vintage swivel lipsticks still work pretty well despite their age. The automatic ones, not so much; many of the ones available for sale are broken. Additionally, even when they do work as they should, they were really no quicker or easier – for the Coty Periscope and its copycats (Constance Bennett Flipstick and the So-Fis-Tik), for example, I found two hands were still necessary.

Vibrating Mascaras

2008-2009

Vibrating mascara wands existed at least as far back as 2005, but it was around 2008 that the major cosmetic companies began taking the gadget mainstream. Estée Lauder's Turbo Lash was introduced in July 2008, followed by Lancome's Oscillation (with 7,000 "micro-oscillations per second") that fall. Maybelline's Pulse Perfection arrived in spring 2009. Unlike, say, an electric toothbrush, which actually can help ensure a more thorough cleaning, most reviewers agreed that a vibrating mascara does not significantly improve application. It also seems users had to learn how to maneuver the wand carefully so as not to poke their eye or create a mess. As one PR exec explained, "[The customer] needs to understand how to use it." Some makeup techniques are worth putting the effort into figuring out, but mascara application should not require a learning curve – like lipstick, a basic level of application is intuitive. As I predicted, vibrating mascaras were indeed a flash in the pan.

Honorable mentions: Bourjois and Dior 360 Mascaras (2011), which rotated instead of vibrated, and MAC Rollerwheel eyeliner, a.k.a. the "pizza cutter" liner.

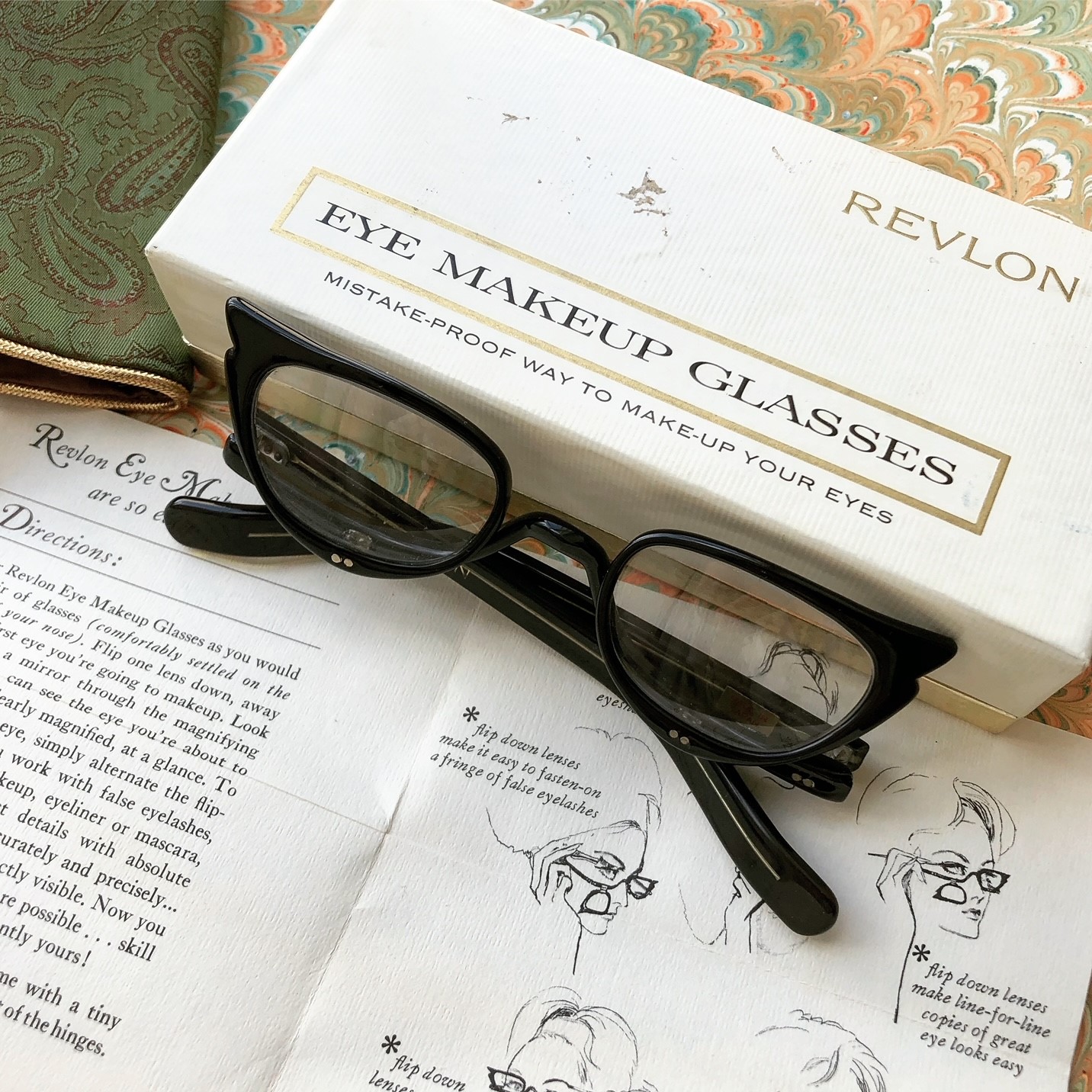

Revlon Eye Makeup Glasses

1966-1973

My appreciable nearsightedness greatly impedes my ability to apply makeup – a big reason for switching to contacts 30 years ago. Back in the 1960s, however, contacts were not as commonplace. So what was the gal with glasses to do? Enter Revlon's flip-up magnifying glasses, which were intended specifically for wearing during makeup application. Rest assured I have tried them out, along with magnifying mirrors and such, and nothing works quite like getting about 1-2 inches away from a regular mirror and applying with short-handled brushes and mini-sized pencils (regular sized products prevent you from getting close enough to see what you're doing as the handles keep poking the mirror.) Other companies make similar versions of these glasses today, so I guess maybe they're not a total fail, but trust me when I say there are much more efficient ways for nearsighted folks to apply makeup.

Lipstick Tissues

1930s-1960s

You can check out my post from 2017 for the full scoop on lipstick tissues, but suffice it to say they failed because they were largely useless. To pull in more dollars, in 1937 Kleenex, building on previous patents, invented a solution to a completely fictional problem: the social crime of leaving lipstick traces on linens and towels, or heaven forbid, a woman's (male) significant other. As I noted in my post, there was no reason why one couldn't use regular facial blotting sheets for lipstick as they work just as well – separate lipstick tissues were wholly unnecessary.

I'm a bit hypocritical, however, since I think it might be fun to bring them back. I even had the husband make a little mockup of Makeup Museum branded lipstick tissues. Would you buy these if you saw them in the museum's gift shop?

Honorable mention: Not makeup, but cigarettes with a red tip so as to disguise any lipstick smears.

The Estée Edit

2016

With much fanfare, in 2016 Estee Lauder unveiled a diffusion line targeted at the Millennial generation. Despite an extensive campaign starring the hugely influential Kendall Jenner and a whole brick-and-mortar store in London, the Estée Edit folded roughly a year after its initial launch.

So what went wrong? The official stance was that the Edit didn't sell because Estee Lauder already had Millennials buying their products, so a separate line wasn't necessary: "Estée Lauder created The Estée Edit collection for Sephora to recruit millennial consumers. Simultaneous efforts by the core Estée Lauder brand have recruited millennials via digital and makeup at an unprecedented rate. Therefore, after a year of valuable insights and learnings, we have decided that a separate brand in North America dedicated to recruiting millennials is no longer necessary."

(image from globalcosmeticsnews.com)

Sounds like Estee was just trying to save face. What really happened is that customers saw through their pathetic attempt at being "edgy" to court a younger demographic. Frankly, the Edit reeked of desperation to revamp Estee Lauder as a youth-oriented brand, and customers could smell it a mile away. Devoid of any real innovation or inspiration, the Edit was also out of touch with the needs and wants of Millennials – the whole shebang was basically this classic scene from 30 Rock.

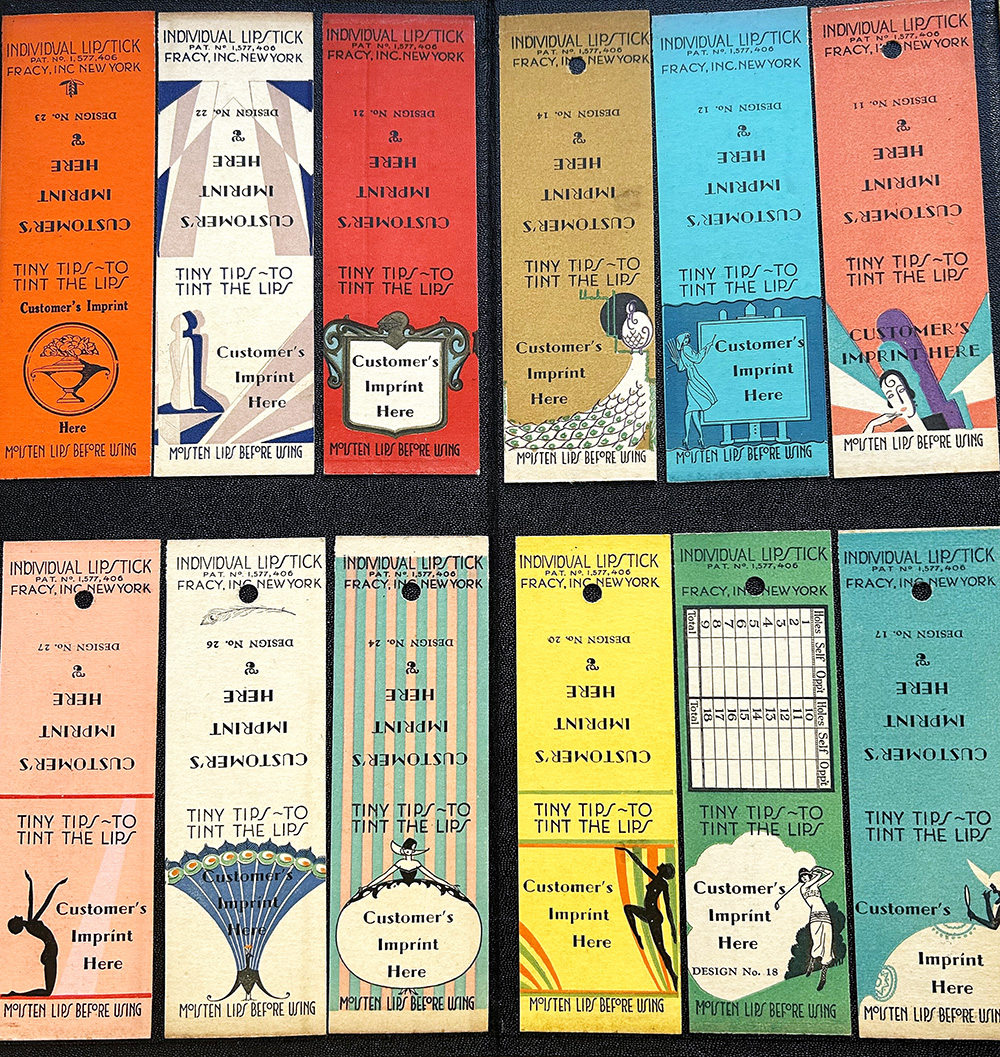

Lipstick Matches

1920s-1950s

As the makeup industry grew exponentially in the early 1920s, companies explored many different designs and packaging. The Parisian firm Fracy introduced "allumettes" lipstick matches around 1924. These single-use items were advertised as being more sanitary than regular tube lipsticks and portable due to their miniature stature. And, like lipstick tissues, they made great hostess gifts or customer freebies for businesses. But were they superior to regular lipsticks? Probably not. Water or saliva was needed to get the dry pigment to adhere so the formula probably wasn't the most comfortable, and the packs sold without a fancy mirrored case negated the "on-the-go" aspect. (I don't know about you, but I find it impossible to apply lip color without a mirror.)

By the 1950s, companies shifted to advertising lipstick matches not as more sanitary, but a fun way to try new lipstick shades without committing to a full tube.

Still, mini versions of products with the same or similar packaging as their full-sized counterparts proved much more popular for sampling makeup, and they were easier to produce. With all angles of promoting matchbook makeup as better than other designs exhausted, it quietly faded from the market.

Mainstream Men's Makeup Brands

ca. 2000-2008

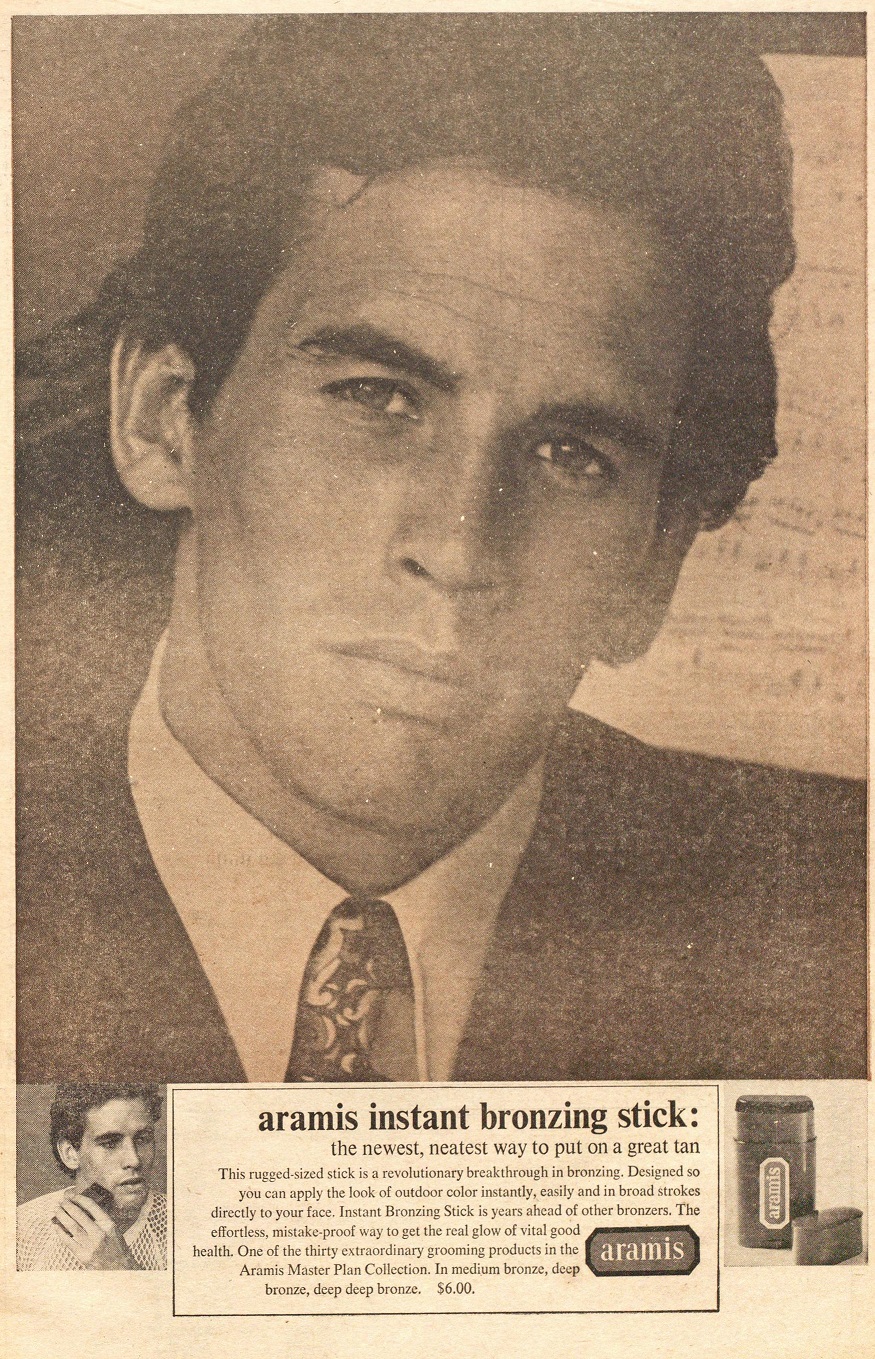

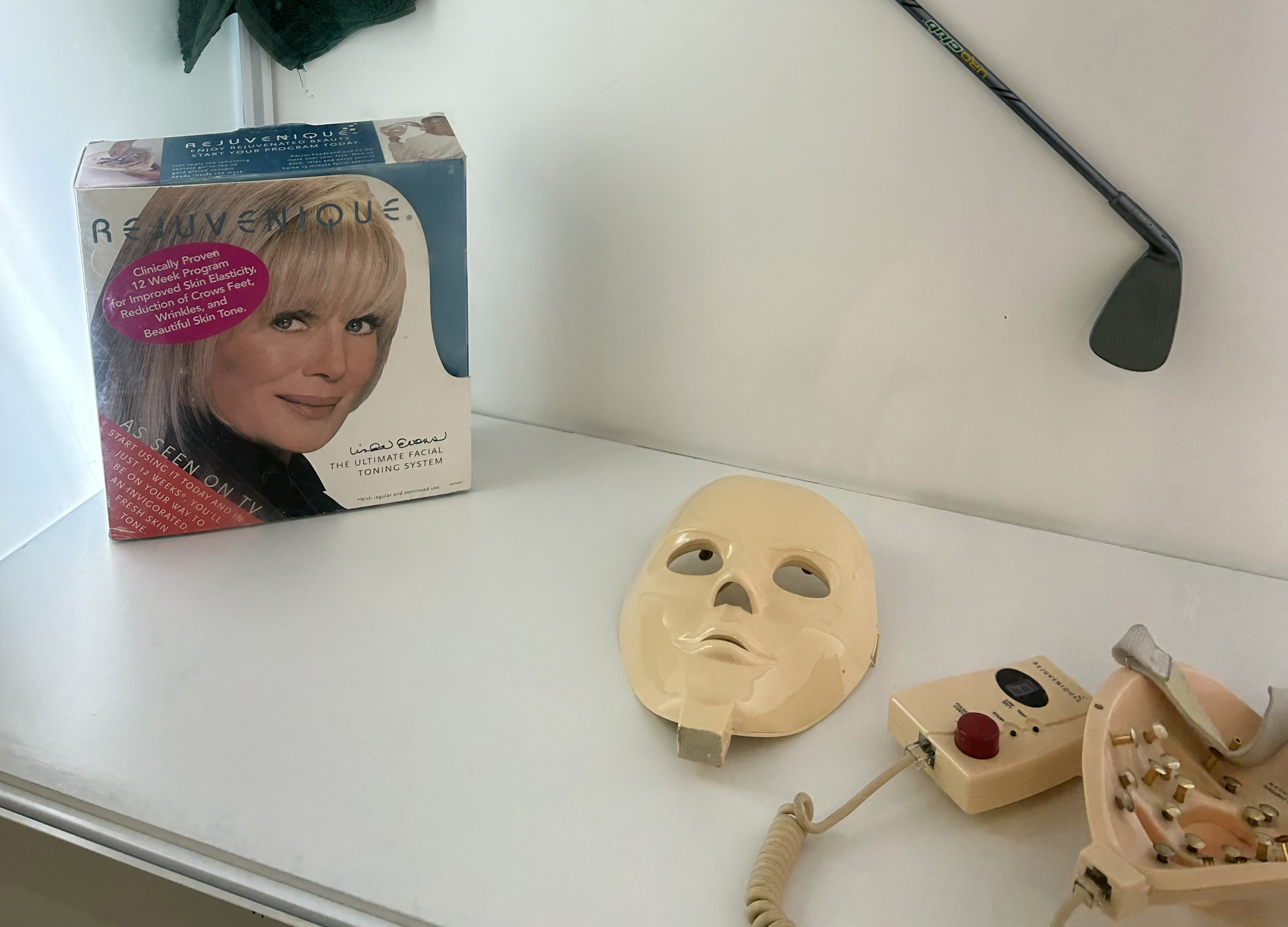

I'm not going into a whole history of men's makeup here – it's another topic the Makeup Museum will tackle eventually – but I did want to highlight the failure of men's makeup to become as ubiquitous as that for women. Makeup has been worn by all genders for millennia, but you would never know it looking at most 20th century cosmetics. Makeup was advertised as being strictly the domain of women. While it was acceptable for men to wear makeup for the stage and screen, it was largely frowned upon for the average cis-het man. Cosmetic companies managed to profit from men by introducing toiletries such as after-shave, hair gel and cologne and developed entire grooming brands exclusively for men, but color cosmetics were still a no-go. However, much like makeup for Black customers, some of the larger companies launched men's makeup to tap into what they thought could be an additional cash cow. For the most part, unlike other grooming products, big brands' attempts at makeup for men consistently failed. It's not clear when the first men's makeup brand on the commercial market was introduced; there were some individual products such as concealers to cover beard stubble and "after-shave talc" used as face powder as far back as the 1930s, and some brands added one-off men's makeup items to their regular lines – for example, Aramis Bronzing Stick and Mary Quant's Colouring Box in the '70s and Guerlain's Terracotta Pour Homme in the '80s. And there were companies like Biba and Manic Panic and later, MAC, that intended their products to be genderless.

But it seems the first complete lines of makeup for men by a mainstream, non-niche company did not appear until the 2000s in the U.S.* And neither of these are still around. Aramis released Surface in 2000, which contained "correctors" (concealers), a bronzing gel and mattifying gel, followed by Jean Paul Gaultier's Le Male Tout Beau in 2003. Tout Beau was discontinued and relaunched as Monsieur in 2008.

Indie brands that were started around the same time such as 4Voo somehow managed to outlast their big league competitors. With so many more resources than small companies, why did Aramis and Le Male/Monsieur fail? I think the industry shot itself in the foot, so to speak. Perhaps if it hadn't spent roughly 100 years and billions of dollars enforcing makeup usage along a rigid binary and making it socially acceptable only for women, more mainstream brands for men would be successful. The modern industry really entrenched the ancient notion of everyday makeup as solely a feminine pursuit, and it's going to take a long time to undo that sort of brainwashing on a mass scale.

So that's just the tip of the makeup failure iceberg. These were interesting, but it's equally fascinating to see what has actually stuck around.

What do you think? And did you ever experience a makeup fail?

*Japan's Kose had introduced a line in Tokyo in 1985, and this hunky gentleman prepared to launch a small brand in 1993, which never came to fruition. Other niche brands included Male Man Unlimited (1980), Marcos for Men (1996), Menaji (1997) and Hard Candy's short-lived nail polish line for men called Candy Man (1997).