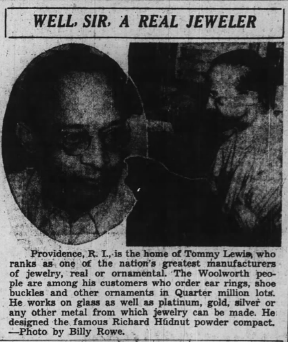

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

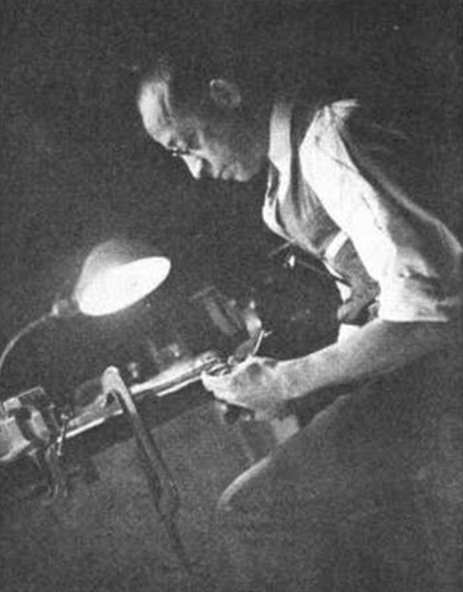

According to another article written in 1935 that I found online, Lewis was born into an impoverished family in Providence, Rhode Island. Undaunted by his circumstances and without the support of his parents or siblings, he attended RISD with the hopes of becoming a jeweler, earning a scholarship in the process. After graduating he worked for a leading jewelry manufacturer in Providence for several years, then struck out on his own.

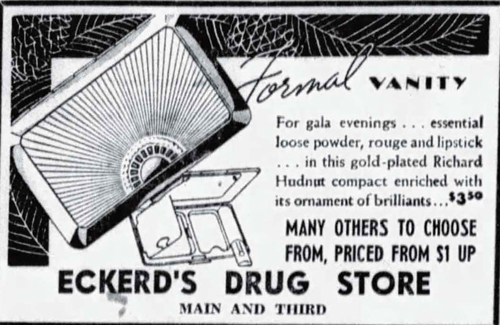

I was unable to find the date he started his company or much other information besides what was in these two articles. The 1935 online article says that he started his business 27 years prior, so I’m assuming he established it in 1908; however, the 1938 article says that he had been in business for 26 years, so maybe it was 1912. And there’s no information on his relationship with Hudnut other than what was in that article, so when he started making compacts for them is unclear. The only (rather patronizing) mention is as follows:1 “Visit the cosmetics department in any first class store, ask the clerk to show you a Richard Hudnut powder compact and then surprise him by telling him that he is looking at the work of a [Black] man. Everyone of those compacts was designed and produced here in a plant at 19 Calendar Street, the home of the Lewis Jewelry Manufacturing Firm. The same is true of their perfume bottles, for Mr. Lewis works on glass as well as platinum, gold, silver or any other metal from which jewelry or ornaments can be made. The Richard Hudnut people are among his biggest customers, but not his most consistent. That honor is reserved for other jewelry manufacturers who regularly send in their commissions for original designs in bracelets, watch chains and other novelty jewelry.” So it seems that while Hudnut was not the biggest source of business for Lewis’s company, we know that he was designing all of their compacts by 1938, and presumably earlier. When I purchased these compacts for the Museum I made sure to select ones that I could get specific dates for, i.e. compacts that were plausibly produced by Lewis given the approximate timeline, and also ones that seemed to be the most jewelry-inspired.

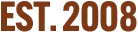

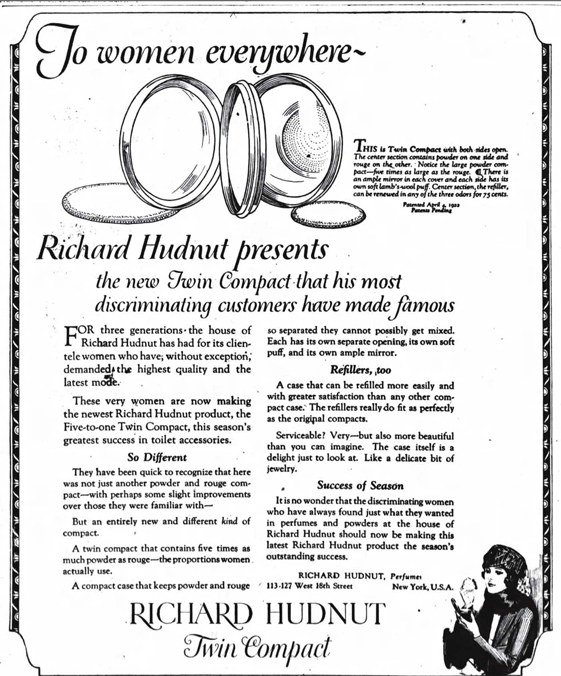

First up is the original “twin” compact, which was introduced in late 1922. I didn’t realize this until after I bought it, but this double case was designed by a man named Ralph Wilson in 1921 and patented in early 1922. Wilson was the New York representative for Theodore W. Foster and Bro. Company, a prominent compact and jewelry manufacturer. Foster, like Lewis, was also based in Providence, so maybe there might be some connection between this company and Lewis’s – perhaps this is the company Lewis worked for after graduating from RISD? In any case, we have proof that the twin compact was created by a company other than Lewis’s, so this is not his work. I still like to think, though, that Lewis may have apprenticed with Foster, grew familiar with Hudnut’s aesthetic and went on to earn the company’s favor over Foster.

How cool is this? You flip over the blush and there’s powder on the other side. Genius.

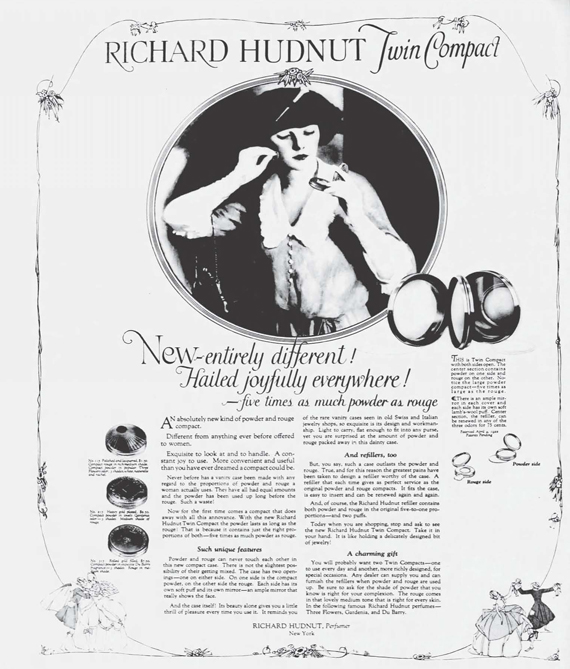

Hudnut’s Deauville fragrance was introduced in 1924. Again, no telling whether this was done by Lewis, but probably not given that it’s basically the same interior mechanism as the earlier twin compact.

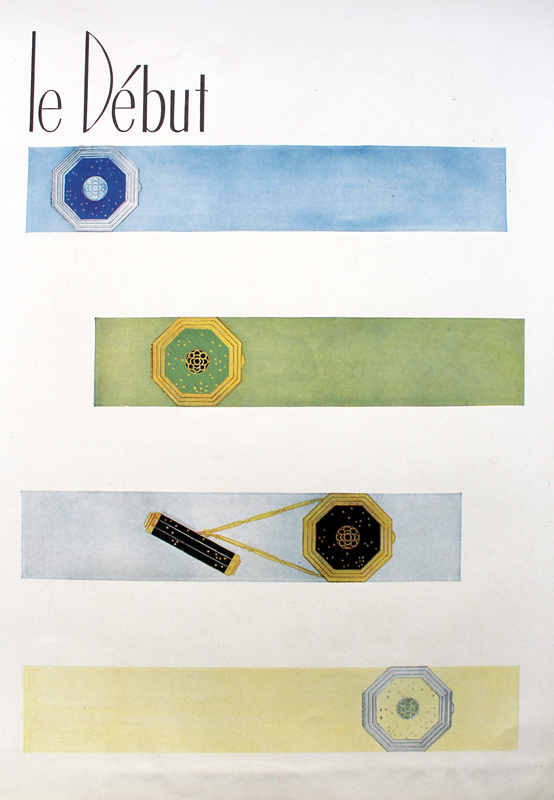

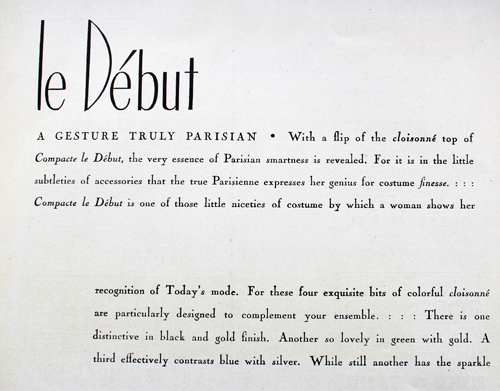

Le Début, a fragrance available in 5 different variants that were color-coordinated to their bottles and powder compacts, well, debuted in 1927. I was fortunate enough to track down an original ad for these beauties. They’re actually pretty common – I was able to find all the colors shown in the ad – but in the end I thought the black one was the most elegant. (Okay, I really love the silver one too!)

In the 1938 photo below it states that Lewis designed the “famous Richard Hudnut compact”, but I really have no idea which one they’re referring to. It could be Le Début, or it could be the “triple vanity” compacts designed in the mid ’30s.

This enameled, oh-so-Deco case came out in 1936, according to the newspaper ads I found, and the last mention of it was in 1938. Again, it’s funny how certain objects call to you. This one was also available in a variety of colors, but I just knew the red belonged in the Museum.

The triple vanities had three compartments for powder, blush and lipstick.

The ad also mentions jewelry several times, so I’m hopeful it was made by Lewis’s hand.

Lastly, I picked up this stunner, which dates to about 1939. Evidently between this one, the Three Flowers compact and the silver Evans compacts I have a thing for sunburst patterns, probably because they remind me of glorious sunny days.

How exquisite is this jewel detail? And in such impeccable shape for a nearly 80 year-old compact – it’s mind-boggling that none of the stones are missing.

To give you a sense of how dainty and small these triple vanities are, here they are with one of NARS’ highlighting trios.

Getting back to Lewis, I can’t say for sure whether his company was responsible for any of these compacts; I can only hope at least some of these jewelry-inspired designs were his. The fact that the 1935 article doesn’t specifically mention Richard Hudnut makes me think that perhaps Lewis wasn’t designing compacts for Hudnut until somewhere between 1936-1938. But it’s also entirely possible he had been producing compacts for them for years. In any case, I want to highlight just how difficult it was for a Black man in the 1900s to not only get out of poverty, but graduate from one of the top design schools in the country AND start his own business that eventually employed up to 60 workers in the busy seasons. As the 1935 profile states: “But jeweler, designer, silversmith? What chance would he have? Where could he work? Who ever heard of a [Black] man, a designer, a master craftsman in the jewelry trade of all trades! One can imagine what would have been Lewis’s fate if his ambitions had been left in the hands of some of the so-called vocational guidance counselors who are at the present time shaping the lifework of many [Black] students in the public schools of our large cities. According to the formula which they use, there are no [Black] jewelers now in existence, hence no future; it would be impossible for a [Black] silversmith to get a job since he cannot belong to the union, and the white jewelers would not employ him anyhow.” Through incredibly hard work and innate talent, Lewis persevered, not only becoming a success himself but also helping others do the same. Most of his employees were Black, and Lewis provided them with better wages than other jewelry firms in Providence as well as training.

I just wish I could have found more information and photos to make for a somewhat complete biography. Searching online for Lewis’s company yielded nothing, as did basic searches for Lewis himself. I ended up contacting the Rhode Island Historical Society and they kindly provided census records indicating his year of birth (1880), but said they didn’t have any business records related to Lewis’s company, which I think is bizarre. If it was as prolific as the articles claim it was, and if it really did provide hundreds of thousands of pieces of costume jewelry to the likes of Saks and Woolworth’s and compacts for Hudnut, I find it very strange that there are absolutely zero traces of his company left save for these two profiles. Especially since the 1938 article even gives the address of his workshop – with that specific type of information there should be historic maps or architectural records listing it. He also apparently had over 200 patents to his name, none of which I was able to find. I guess the saddest part is that there are tons of other stories like Lewis’s, and we simply don’t hear about them. So many histories for non-white people are erased or buried, and I really wanted to bring Lewis’s story to the surface because it was truly outstanding (and not only because it’s Black History Month…I just so happened to find the newspaper article around a month ago and thought the timing worked out nicely). I really hope this post didn’t come across as patronizing or me highlighting a “token” Black person.2 I find Lewis’s story impressive not because I can’t believe a Black man could ever be creative and intelligent enough to start a jewelry firm, but because of all he had to overcome to achieve his goals. “Perhaps it is the memory of a [Black] boy with a dream to become a jeweler, a silversmith, a designer, a [Black] boy who kept his dream despite the doubts of his family from within and racial prejudice from without. For Thomas Lewis is an artist and so he believes in young men and young women with dreams.”

Thoughts?

Update, 11/24/2022: One of the Museum’s Instagram followers alerted me to a video made by a vintage compact collector who mentioned Tommy Lewis while showing some of her Hudnut collection. It got me thinking whether anything else on Lewis had been discovered and lo and behold, two students from Rhode Island College were able to unearth some more information, including a map showing where his store and factory were! While it didn’t shed any light on Lewis’s relationship with the Hudnut company, their article surely adds more to this important piece of history. Lewis was born on April 5, 1880 and graduated from RISD in 1902. In 1925 a lacquer explosion caused a fire at Lewis’s shop located at 171 Eddy Street, which damaged much of the building. I’m wondering if some of the early business records were lost in that fire. Throughout his life, in addition to providing training and employment for Black workers, he was a philanthropist and active in the YMCA and other community organizations. Lewis passed away in 1958. I can only hope someone writes a full biography of this exceptionally talented man, but in the meantime sure to check out the article at rhodetour.org. Oh, and they even included the Makeup Museum’s original article as a “related resource”. I’m so honored!

1 I spent several hours googling whether it was acceptable to type the word “c*lored” if I was quoting from an old newspaper article. In the end I realized I personally didn’t feel comfortable using it even if it was a quote, so I replaced it with “black”.

2 I rarely, if ever, highlight makeup histories featuring people of color, i.e. Madam C.J. Walker, Annie Turnbo Malone, etc. because I’m not sure whether it’s okay for a white person to do that – while I think their stories absolutely need to be heard and recorded, once again I fear that it would come off as whitesplaining or tokenizing if I attempted to write about them. In the case of Tommy Lewis, there was such scant information available I’d figure I’d make an exception in order to at least introduce him and his work.