Before I get to my review of Susan Stewart's Painted Faces, I must disclose that I received a copy for free from the author. In no way, shape or form did getting it for free influence my review, nor was it intended as a bribe for a positive one – I believe I was given a copy in exchange for me lending photos of some of the Museum's collection to be included in the book. Not only did Dr. Stewart provide an autograph, she also included me in the acknowledgements, which was incredibly kind.

Again though, I'd like to reiterate that this did not sway my opinion of the book at all. Now that that's out of the way, I can dive into the review.

The goal of Painted Faces is much the same as Lisa Eldridge's Face Paint in that it strives to provide a history of makeup from ancient times to the present day. However, a trained scholar/historian approaches this vast topic in a markedly different way than a makeup artist such as Eldridge. Neither perspective is better or worse than the other; ways to tell the story of makeup are nearly as varied as the people who wear it. Nor do I believe one has to have a set of particular credentials to write accurately and compellingly about makeup history, as I believe it comes down to a matter of preference for a certain writing style. As we saw with her first book, Painted Faces is more academic than Face Paint and relies on highlighting the economic and sociological aspects behind various beauty practices, whereas Eldridge adopts a more artistic tone, choosing instead to communicate makeup's history by focusing on application and styles as they evolved.

Stewart begins with an introduction (which also serves as the first chapter) summarizing the need to study makeup and beauty practices as it gives valuable insight into history that we may not have considered before. "Because of its wider significance, researching makeup, its uses, ingredients, its context and application, can provide clues not only to the nature and circumstance of the individual but can also help us to interpret the social, economic and political condition of society as a whole in any given period. That is to say, studying cosmetics can further our understanding of history…they are a window into the past and can encapsulate the hopes and ideas of the future. In short, makeup matters" (p. 8 and 10). Can I get an amen?! Stewart also carefully sets the parameters for the book, outlining the sources used and why she is primarily writing about cosmetics in the Western world.

Chapter 2 is essentially a condensed version of Stewart's previous tome on cosmetics in the ancient world, which doesn't need to be rehashed here (you can check out my review of that one to peruse the content). That's no small feat, considering how thorough it was. The next chapter covers the Middle Ages, which is interesting in and of itself since so little information about makeup and beauty exist from this era. As Stewart points out, the rise of Christianity meant people were no longer being interred with their possessions as they were in ancient Greece and Rome – these artifacts provided a wealth of knowledge about beauty practices then. Thus, any time after the spread of Christianity and before the modern age historians must rely primarily on texts, such as surviving beauty recipes and classic literature, rather than objects to infer any information about the use of makeup and other beauty items. The dominance of this religion also meant even more impossible beauty standards for women and more shame for daring to participate in beauty rituals. "According to medieval religious ideology, wearing makeup was not only the deceitful and immoral – it was a crime against God" (p. 60). The other interesting, albeit twisted way Christianity affected beauty is the relentless belief that unblemished skin = moral person. Something as innocuous as freckles were the mark of the devil, and most women went to great lengths to get rid of them or cover them so as not be accused of being a witch. I shudder thinking about those who were affected by acne.

Chapter 4, which discusses beauty in the late 15th and early 16th centuries (i.e., approximately the Renaissance) presents the continuation of certain beauty standards – pale, unblemished skin on both the face and hands, a high forehead, barely there blush and a hint of natural color on the lips- as well as judgement of those who wore cosmetics. As we saw previously, it's the old "look perfect but don't use makeup to achieve said perfection" deal – women who wore makeup were viewed as dishonest, vain sinners. But one's looks mattered greatly in the acquisition of a husband, so many women didn't have a choice. "Clearly a woman had to get her makeup just right not simply for maximum effect but to avoid getting it wrong and spoiling the illusion of youth and beauty entirely, a fault that could cost her dearly in terms of wealth, status and security" (p. 94).

However, there were some notable differences between the Renaissance and medieval periods. For starters, due to inventions such as the printing press, beauty recipes were able to be much more widely disseminated than they were previously. Increased trade meant more people could get their hands on ingredients for these recipes. Both of these developments led to women below the higher rungs of society (i.e. the middle class) to start wearing cosmetics. So widespread was cosmetics usage at this point, Stewart notes, that the question became what kind of makeup to wear instead of whether to wear it at all.

This chapter was probably the most similar to those on Renaissance beauty in Sarah Jane Downing's book, Beauty and Cosmetics: 1550-1950. Given the lack of information regarding cosmetics during this time period, both authors had to draw on the same sources to describe beauty habits. However, as with Eldridge, the approaches Downing and Stewart take are slightly different. Once again, Stewart opts for a straighter historical approach whereas Downing looks more to paintings and literature of the time, and doesn't take quite as deep a dive into the larger social and economic forces at work. There's also not much overlap between the descriptions of recipes and techniques, as you'll find different ones in each book. For example, one that was mentioned only in passing in Downing's book was using egg white to set makeup. I'm thinking of it as a early version of an illuminating setting spray (although obviously it was brushed on, not sprayed in a bottle) as it lent a slightly luminous, glazed sheen. Stewart points out that it also caused one's face to crack, thereby eliminating the wearer's ability to make any sort of facial expression. It seems certain beauty treatments, whether egg white or Botox, occasionally come with the side effect of suppressing women's expression of emotion. Coincidence? I think not.

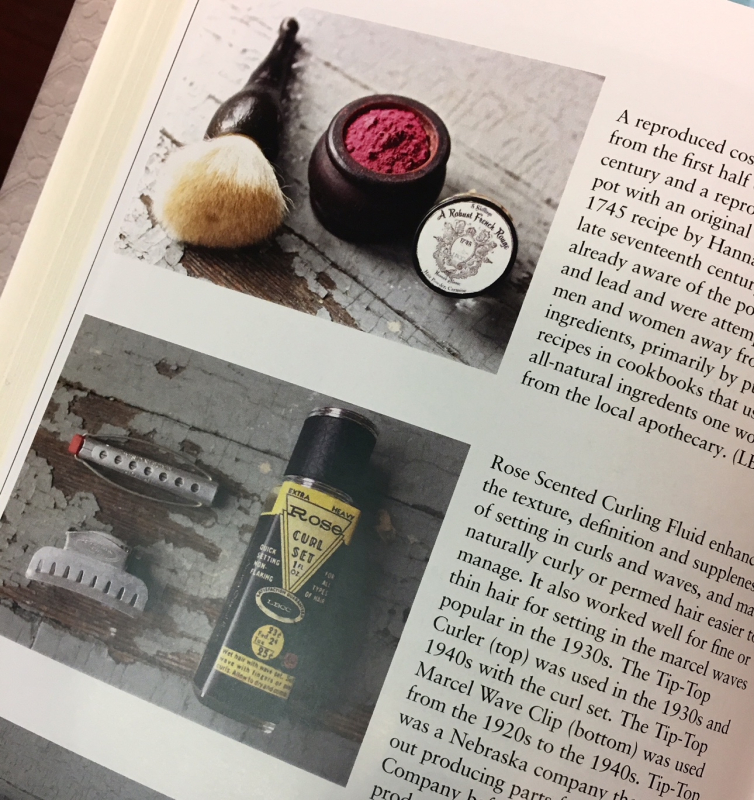

Chapters 5 and 6 are tidily sequential, discussing beauty during the the 17th and 18th centuries, respectively. As in the Renaissance, both eras witnessed significant growth in the number of women who wore makeup due to technological advances and increased trade. Growing literacy rates drove demand for the new medium of ladies' magazines. Pharmacies selling raw materials to make beauty treatments had started to crop up in the 17th century and their numbers increased dramatically by the beginning of the 18th century. Not only that, pharmacies and chemists started offering their own pre-made formulas, and these goods became commercially exported to other countries. The widespread sale of these products came with several undesirable effects: counterfeit cosmetics and downright false claims about the product's efficacy.

The 1700s also saw the rise of excessive, decidedly unnatural makeup being worn by members of the aristocracy in both France and England, followed by a post-French Revolution return to more subtle makeup in the early 1800s. This brings us to Chapter 7, which outlines the myriad changes leading to what would become the modern beauty industry, including department stores, industrialization and the new commercial market of the U.S. As for beauty standards, a natural look was still strongly preferred by both men and women, with the emphasis in terms of products on skincare rather than color cosmetics. Here's a literal lightbulb moment: despite my research on Shiseido's color-correcting powders, in which I learned some were meant to counterbalance the effects of harsh lighting, I had completely overlooked the influence of artificial light on the skyrocketing production of face powders. "Suffice it to say that in the early years of the twentieth century, the use of artificial light in homes of the wealthy as well as in public places such as theatres and concert halls would become more widespread, in the latter years of the nineteenth century there was already an understanding that to make the best impression, makeup needed adjusting to suit the light, whether it be natural or artificial" (p.198).

Chapter 8 leads us into the 20th century. While there are more detailed accounts of makeup during this time, Stewart does an excellent job describing the major cultural and technological influences that shaped modern beauty trends and the industry as a whole. I was very impressed with how she was able to narrow down the key points about 20th century beauty without regurgitating or simply summarizing other people's work. Some of the information presented is familiar, of course, but the manner in which it's arranged and categorized sets it apart. It just goes to show that everyone's individual background equals an infinite number of ways to tell the story of makeup.

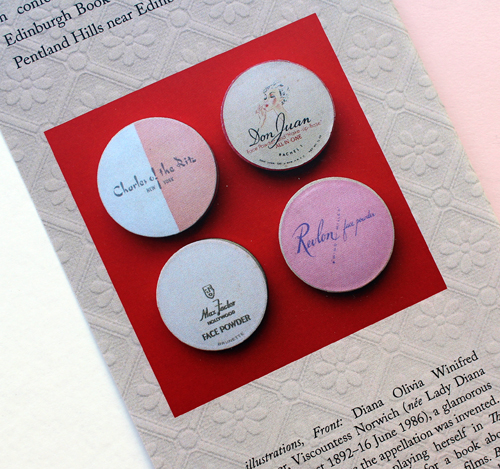

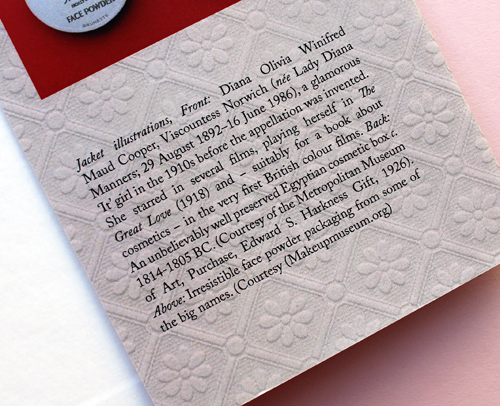

I'm partial to this chapter since the items I took photos of for the book are all from the 20th century. :)

Here are some powder boxes on the dust jacket.

While I was deliriously happy to see some of the Museum's items in a real published book and get credited for them, I was also pleased to see photos of other pieces as well. Their inclusion in addition to illustrations was a bit of an upgrade to Stewart's previous book. This is a minor issue to be sure, as I believe solid writing more than makes up for a lack of photos, but they are a nice touch if available.

The last chapter serves as an addendum in which Stewart reflects on how the past, present and future of beauty are linked, noting that while some things have stayed the same – the use of ancient ingredients in modern formulas, the connection between health and beauty – 21st century attitudes towards cosmetics represent a significant change from earlier times.

Overall, this is a more scholarly history of makeup than we've seen before, but by no means dry and boring. Stewart's gift for wading through hundreds of historical documents and neatly consolidating the major social, economic and cultural forces that shaped makeup's history, all while sharing fascinating snippets such as ancient beauty recipes and anecdotes from people who lived during the various eras she covered, makes for a thoroughly engaging read.

Will you be picking this one up?