I admit I purchased this object without fully understanding what it was.

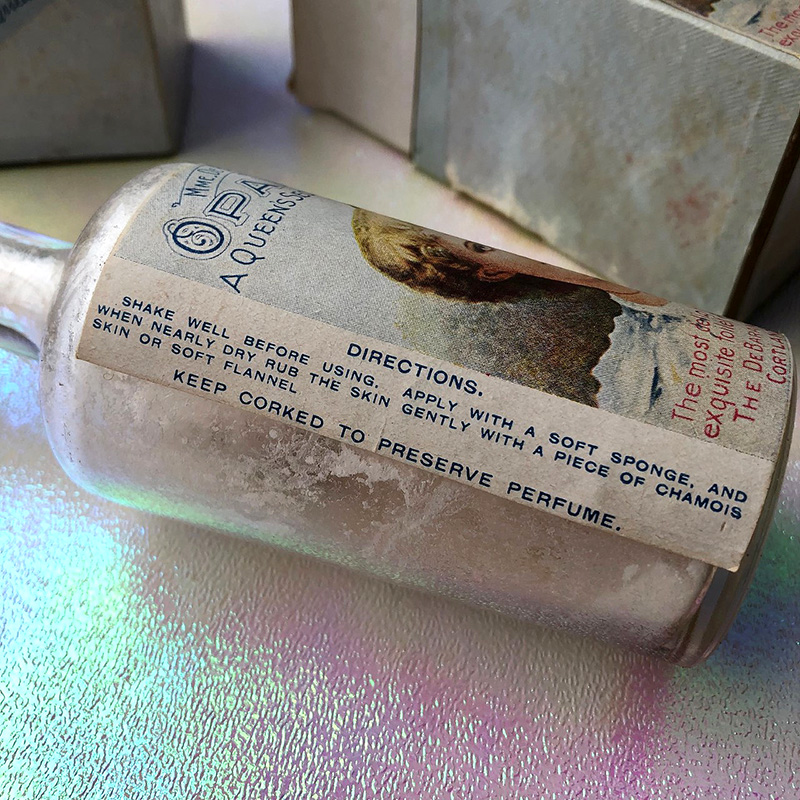

I couldn't unearth any ads for Opaline1 and very little exists about the company. There were a couple calls for De Baranta-Windsor salespeople in 1898 for totally different products – no mention of beauty preparations, so I had to rely on other clues to suss out what Opaline could possibly be. The substance appears to be a powder in the bottle, but there were a few reasons why I didn't believe it was a face powder upon closer inspection. Namely: 1. powders were normally packaged in boxes, not bottles; 2. the directions instructed the user to shake well and apply with a sponge, and powders did not usually require shaking and were applied with a puff; and 3. the directions also insinuated the product was a liquid by including the phrase "when nearly dry…".

So what exactly was Opaline? Certainly not perfume and most likely not a skincare treatment either. It was clearly some kind of liquid makeup (with the liquid obviously evaporating over time) but not quite foundation as we know it today. Thank goodness for Cosmetics and Skin, as I really didn't know what I was looking at until some frantic Googling led me to their website, which has an excellent summary of the three most common types of "liquid powders" popular at the turn of the 20th century: calamine, wet white and liquid pearl (not to be confused with pearl powder).

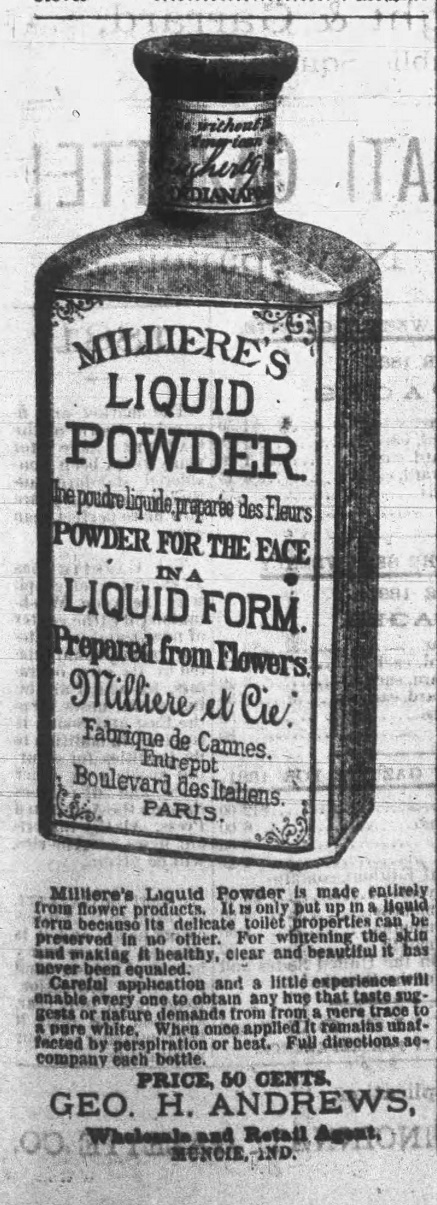

Liquid pearl was essentially white face powder mixed with water and glycerin. Despite its tendency to streak, it had several advantages over dry face powder, namely that it lasted longer and provided slightly more coverage. Although the powder component consisted of the same ingredients as face powder (usually zinc oxide or bismuth oxychloride), liquid pearl was used on the body in addition to the face, primarily for evening wear to impart an even, whitening effect on any exposed skin – ideal for the plunging necklines and short-sleeve styles of fin-de-siècle Europe and the U.S. It was also less frequently recommended as a sort of sunscreen for daytime due to the zinc. Sources detailing liquid pearl from the early 1900s align with Opaline. A 1904 recipe instructed the user to "Keep in a tightly corked bottle and apply with a sponge when required,"2 and in 1910 beauty columnist Margaret Mixter advised, "When bottled there will be a white sediment at the bottom, and the preparation must always be shaken before any is put on the face. In applying a piece of muslin or linen should be used."3 Opaline's name, color, packaging, and instructions perfectly match liquid pearl. Compare to others from the time, which were packaged in bottles and claimed to have a whitening effect.

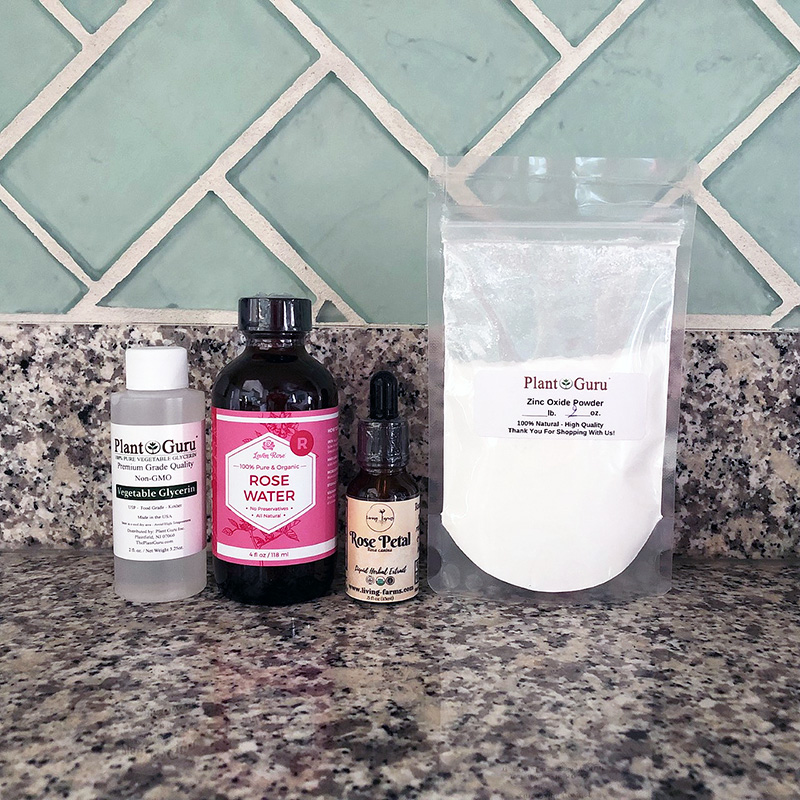

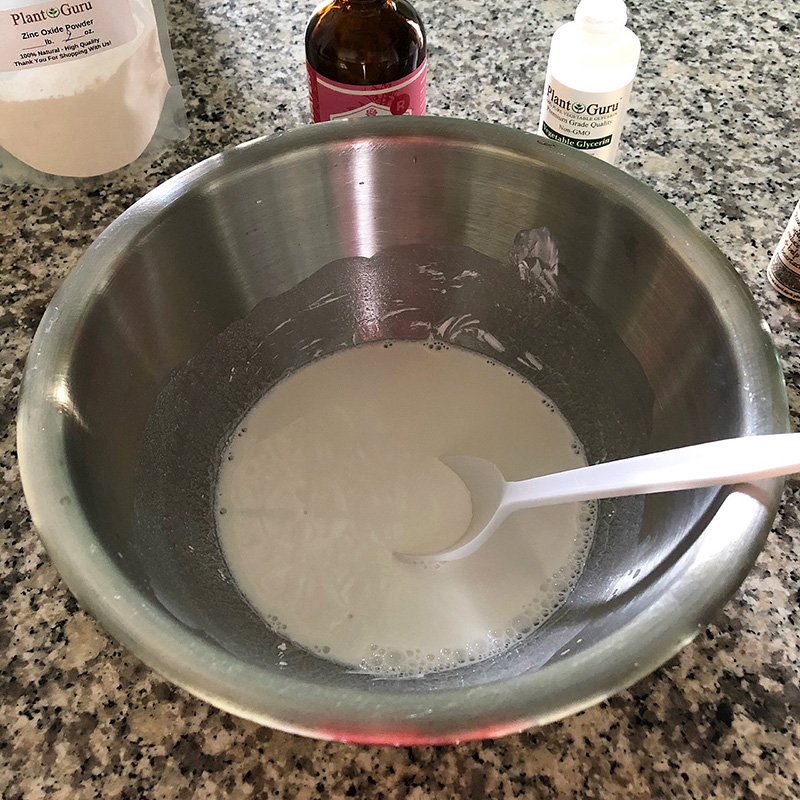

I can't uncork the Opaline bottle due to its fragility, but I was very tempted to try to sprinkle out some powder to get a sense of the texture and opacity. Instead of potentially damaging or breaking the bottle, to sate my curiosity I decided to whip up a batch of liquid pearl using a common recipe – this one appeared in a column by Harriet Hubbard Ayer4 in 1902 and was reprinted in several other beauty guides: "pure oxide of zinc, 1 ounce; glycerine, one dram; rosewater, four ounces; essence of rose, fifteen drops. Sift the zinc, dissolving it in just enough of the rosewater to cover it, then add the glycerin, next the remainder of the rosewater. Shake well and apply with a soft sponge or antiseptic gauze." All ingredients were procured via Etsy.

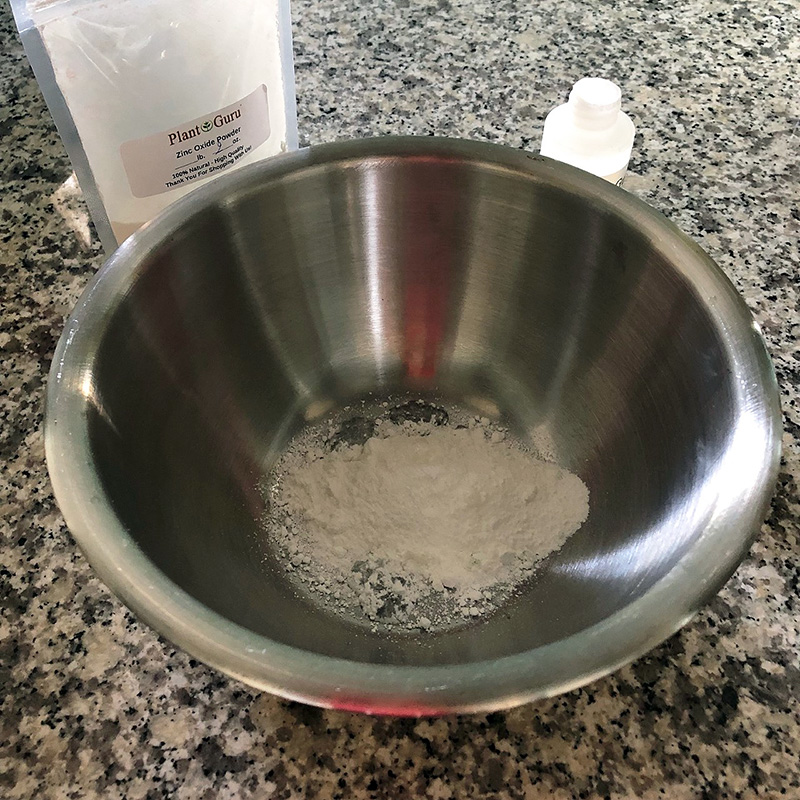

My measuring may have been off, but the mixture ended up being very thin and watery.

I didn't have any cheesecloth on hand to strain it nor a pretty little bottle to put it in, but I did have plenty of travel containers. After a good shake I used my trusty Beauty Blender sponge (dampened) to apply a thin layer – I was also short on linen, muslin and gauze.

Once applied, it's actually not too dissimilar from today's zinc-based sunscreen lotion in that it leaves a pretty noticeable white cast, even with just a small amount on my pasty skin. Smelled lovely though! And the texture was surprisingly smooth and comfortable. Not as emollient as a lotion, but it didn't feel dry or like it was just sitting on top of my skin. I'm sparing you a photo, but I did try it on my face and neck in addition to my inner arm…looked quite ghostly. I also neglected to take a photo of it in the bottle a few hours after, when it had separated with all the zinc on the bottom – the instructions to shake well were definitely necessary.

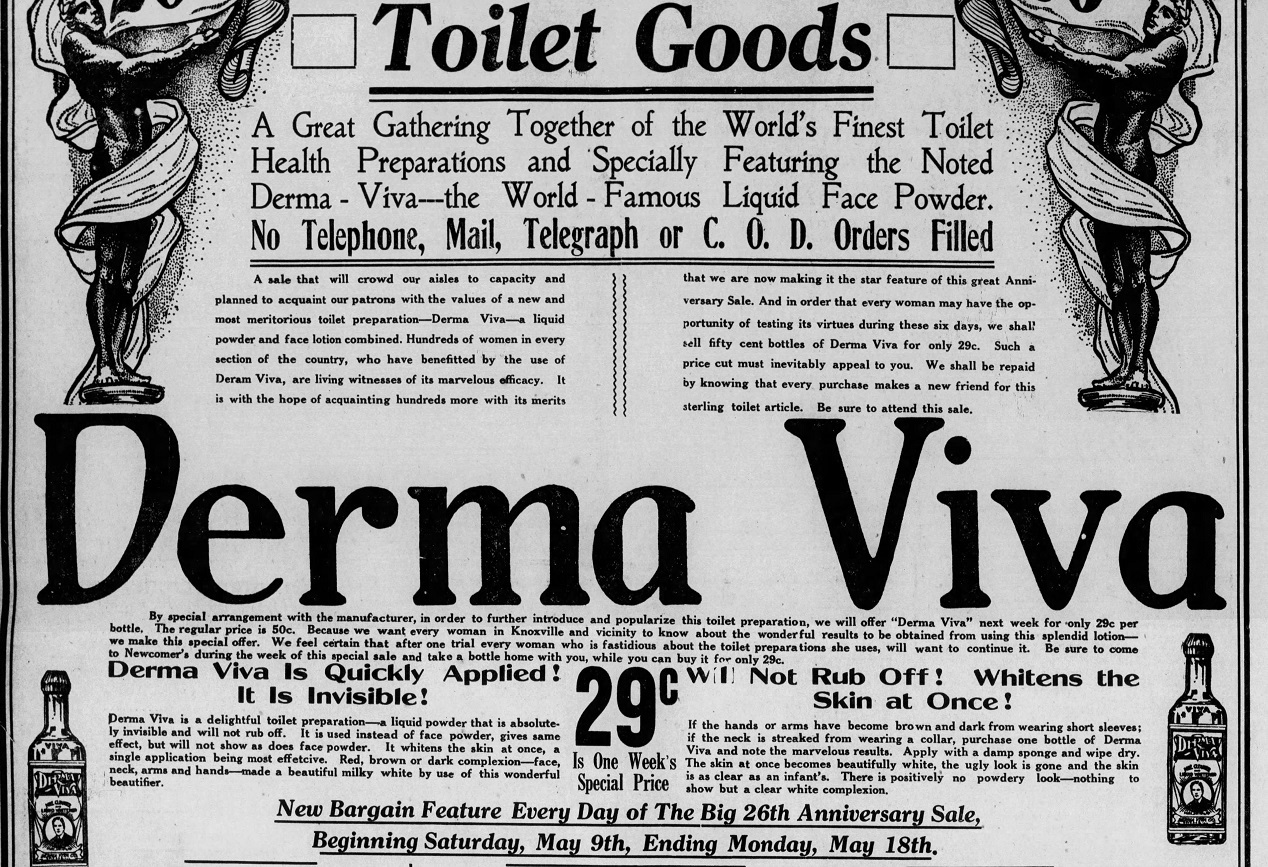

Given its unnatural appearance – I can't imagine putting on more layers – I found myself wondering if liquid pearl was commonly worn. Whiteness was (is) highly prized as a beauty standard, and liquid pearl was one way to achieve it, albeit temporarily. As was the case for centuries, the starkness of ultra-white skin wasn't an issue despite being at odds with the "undetectable" makeup that middle-class women were expected to adhere to; the whiter, the better, especially according to ads for liquid pearl. A 1914 ad for a liquid powder called Derma Viva states, "It whitens the skin at once, a single application being most effective. Red, brown or dark complexion – face, neck, arms, and hands – made a beautiful milky white by use of this wonderful beautifier."

Judging from my experiment, liquid pearl doesn't seem like it would look remotely natural on even the palest of skin tones, but it appears whiteness trumped any concerns about liquid pearl's obviousness. It could also be that as there were so few formulations, liquid pearl and other liquid powders were relatively natural-looking by fin-de-siècle standards, or at least, that's what companies wanted customers to believe. Derma Viva notes that it is "absolutely invisible" and "will not show as does face powder," while Mme. Gage's Imperial Japanese White Lily, "a delicate liquid powder for evening use" was also advertised as invisible. "A successfully made-up woman does not look in the least artificial," proclaimed Mrs. Henry Symes, who then followed up this statement by a recipe for liquid pearl.5 Another column from 1903 advises using one of the new "flesh" tinted liquid powders instead of white, but notes that white powders were still preferable to the harshness of theatrical makeup. "Only a few years ago Milady was forced to be content with just two colors of face powder, chalk white and rose. Both of these were easily discernible, for they made her either too red or too pale…Not only are there fifteen tints of complexion powders, but they are put up in different forms to suit different occasions. There are liquid powders, which are to be 'shaken before taken'…at any big entertainment the women may be seen with their faces chalked till they resemble nothing so much as a company of corpses. These women do not bother about preparing the chalk; they simply take a chalk pencil and rub it into the skin with unction, and the more ghastly the result the better they are pleased."6 Given that every liquid pearl recipe dictated careful application with a sponge or other piece of cloth, it seems that as long as women were using it primarily for nighttime and paying attention to how and where they applied it, liquid pearl was an acceptable cosmetic for the average (white) woman.

We also can't discount the fact that electric lighting wasn't totally ubiquitous at the time and liquid pearl was mostly recommended for evening wear, so perhaps it was less obvious in darkened settings. In any case, while some cosmetic recipes hold up today and all the ingredients in this particular concoction are still used in contemporary cosmetics, it appears quite crude by comparison and is best left in the 1900s.

To conclude, I'm 99.9% sure Opaline is liquid pearl, but less certain is whether Mme. De Baranta was a real person. I am skeptical! Perhaps the Cortland Historical Society, which also has this artifact in their collection, could shed some light on the company.

What do you think of Opaline and liquid pearl? And have you ever tried DIY'ing makeup? Believe it or not, this was my first experiment despite all of the recipes that have been printed in various makeup history books and seeing it done numerous times before. I think recreating old formulas would be pretty fun Makeup Museum events. 😉

1There were several instances of liquid powders named Opaline from the late 1800s/early 1900s including one by UK-based Crown perfumery and the Opaline Toilet Manufacturing Company in San Francisco, but no Opaline from the De Baranta company.

2Emily Lloyd, "The Skin: Its Care and Treatment," (Chicago: MacIntosh Battery and Optical Co) 1904, 104-105. The story of this book's author is fascinating by itself – apparently Emily Lloyd was an alias used by Ruth Maurer, who established the Marinello company. Once again, Cosmetics and Skin has all the details.

3Margaret Mixter, "Health and Beauty Hints," (New York: Cupples and Leon Company) 1910, 118.

4"Harriet Hubbard Ayer Responds to Many Inquiries Directed to the Sunday Post-Dispatch," The St. Louis Sunday Post Dispatch, May 25, 1902, 42.

5Mrs. Henry Symes, "How To Be Healthy and Beautiful: Use of Cosmetics for Improving the Complexion's Appearance – When It Is Justified," The Minneapolis Tribune, February 16, 1902. This entire column is a hoot – Symes basically calls out the hypocrisy of men judging women who wear makeup, and states that if they weren't so obsessed with certain beauty standards, women would not feel the need to wear makeup.

6"The True Uses of Powder for the Complexion," Evening Star (Washington, DC), Nov. 14, 1903, 32.