Tooting my own horn again, apologies. But I was so excited to be interviewed for an article on the history of blush and its current resurgence (and in which I was referred to as an "expert"!) In case you haven't noticed, blush is back with a vengeance. You can click over to Hypebae for the article, but given how much time I spent answering the journalist's questions I thought I'd post my full answers here. Plus, more Museum photos! Enjoy…and please let me know any and all thoughts on blush in the comments. 🙂

Tooting my own horn again, apologies. But I was so excited to be interviewed for an article on the history of blush and its current resurgence (and in which I was referred to as an "expert"!) In case you haven't noticed, blush is back with a vengeance. You can click over to Hypebae for the article, but given how much time I spent answering the journalist's questions I thought I'd post my full answers here. Plus, more Museum photos! Enjoy…and please let me know any and all thoughts on blush in the comments. 🙂

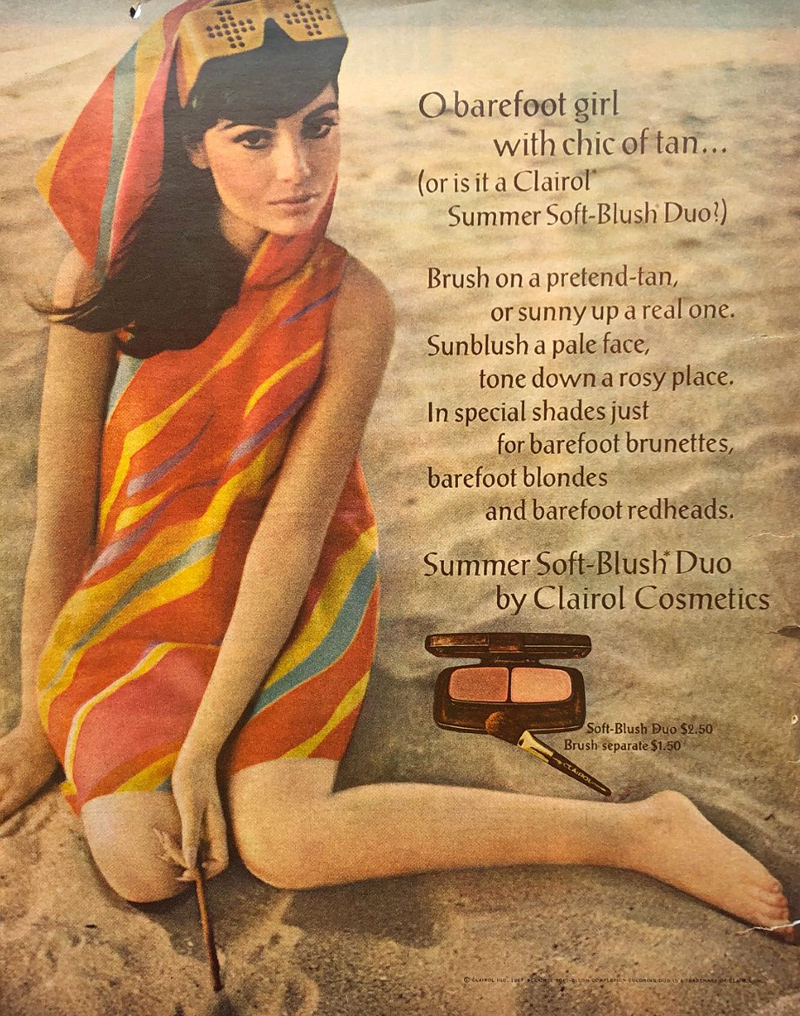

Blush has been used in ancient cultures across Egypt, Greece and more. Can you walk us through the origins of blush and explain how it was used in different areas of the world? (Please feel free to include as much detail as possible.) The ancient Egyptians were most likely the first to use blush as a cosmetic aid. A fresco in Santorini from the Bronze Age depicts women with red cheeks, the rest of their faces unadorned. In China, blush was used as early as the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE). Later, during the Tang Dynasty reign, imperial concubine Yang Guifei (719-746 AD) regularly wore heavy blush at court. In Greece and Rome, blush was primarily used by upper class women and applied in a subtle way; noticeable check color was frowned upon. Blush also crossed gender lines throughout some early civilizations and up through the 18th Over time, as white supremacy grew ever more powerful, blush became part of an “ideal” complexion that signified wealth and high status – blush was used in part as a way to make pale skin stand out more, which was desirable as white skin represented a life free from toiling outside. At the same time, for the most part blush was supposed to be undetectable. It wasn’t until the 20th century that blush became socially acceptable.

Why do you think blush has endured as a widely used makeup product?

Blush has endured primarily because it’s a critical element of meeting two long-standing beauty ideals: health and youth. Cheek color signifies vitality; while I don’t think any live person not wearing blush would be mistaken for a corpse, blush heightens one’s natural color, further emphasizing a healthy flow of oxygenated blood (i.e., a literal life force) to the face. Cheek color became associated with markers of health such as physical fitness, good nutrition and rest. Cheek color is also associated with youth, which has been a pillar in beauty standards for millennia and one that persists today. (Note: I can expand on the link between health, youth and beauty but it would take forever as there are quite complex psychological and scientific explanations).

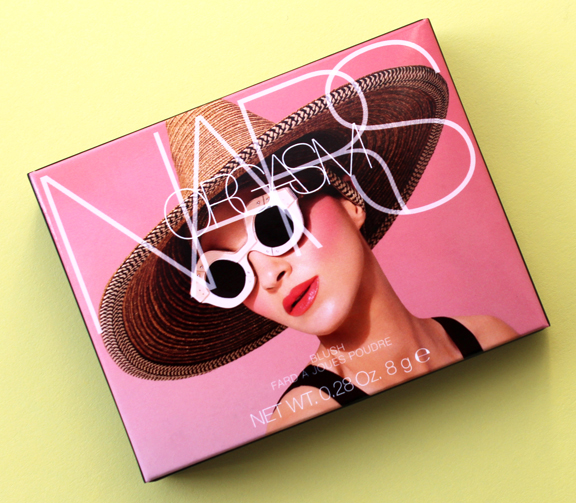

Some historians claim that blush’s universal appeal, much like lip color, is due to its mimicking of sexual arousal or a post-coital flush. While I personally find that theory dubious – I’m just not a fan of the sexualization of makeup – it’s important to remember that the most famous and possibly best-selling blush in modern times is NARS’ Orgasm. Additionally, for centuries in the Western world, with a few exceptions here and there (such as mid-late 18th century France), excessive makeup, including noticeable rouge, was considered the domain of prostitutes, so that’s another connection between blush and sexuality. Along those lines, one could even argue that the traditional virgin-whore dichotomy is a factor in blush’s longevity. Looking flushed could point to embarrassment at the notion of intimate relations, signaling a dainty, demure and virtuous woman, or it could be overtly sexual. Either way, blush’s sexual connotations helped solidify its status as an essential cosmetic. Finally, a simplistic reason for blush enduring through the years was that it was as easy to obtain ingredient-wise as lip color. There were readily available materials across the world. Whether it was the ochre of ancient Egyptians, poisonous cinnabar of the Romans, safflower used in parts of Asia or a basic mixture of berries and water, raw ingredients could be found virtually anywhere.

Blush sales are increasing. In your opinion, what could be contributing to that rise? First, I believe there’s a psychological component involved. Most of us have been privileged enough to work from home, see friends and family via video conference, and were able to adjust our routines, but that all of that has taken a toll on our mental health. Being trapped behind a screen far more than we’re used to, with little in-person contact, struggling to work and interact and essentially function in a completely different way for over a year can lead to feeling drab and lifeless, despite being physically healthy. As noted earlier, cheek color represents vigor and liveliness. This is why every spring fashion and beauty magazines have features on banishing the “winter blahs”, with the number one tip inevitably being the purchase of a new shade of blush to look and feel rejuvenated. Thus, with its promise of restoring a youthful, rested glow, blush may help combat the dullness experienced as a result of having to curtail so many activities that are essential to one’s well-being as well as general pandemic-related exhaustion. As one beauty writer notes, she applied “a generous helping of blush to help me look alive even though on most days I felt dead inside.” I also think that now since the pandemic is on the verge of ending, we are collectively dreaming about fresh starts and enjoying life more fully again. More so than other makeup categories, on a spiritual level the application of blush may help us awaken from the trauma and upheaval unleashed by the pandemic, a way to feel more vibrant and a reminder that our health is relatively intact. On related note, a healthy flush is associated with being outdoors, which many of us haven’t been able to do. If you can’t enjoy a reinvigorating jaunt through nature, you can at least pretend you got the blood flowing with some blush.

Secondly, even though we are optimistically looking towards the end of the age of COVID-19, life has not returned to how it was pre-pandemic for most. Many people are still reconsidering and adjusting all of their makeup, including blush, in light of continuing Zoom calls. Depending on one’s camera and lighting, a person may need to increase the amount of color so as to not appear washed out; in other cases, they’re finding that their regular application is too heavy-handed. Thus, in addition to adapting their current products, they’re seeking either new shades or new formulas that are effortless and “goof-proof” for video.

Finally, I think at the moment the market is so saturated with every other form of makeup – highlighters, (especially!) eye products, lip colors, even base makeup, companies figured it was time to swing the pendulum back to blush. It’s a product category that’s been relatively neglected due to the popularity of contouring and the no-makeup look. But these two trends were already waning, with consumers wanting a simpler approach to cheek color than the skill and time required by contouring as well as a look that was more than the bare minimum of the no-makeup face. Another trend that’s been gaining traction the past few years is the notion of wellness. Consumers are increasingly interested in cosmetic options that might also have benefits for their physical and mental well-being. The pandemic engendered a renewed focus on health, making wellness and self-care more important to consumers than before. It follows that blush, and its long-standing association with health, would be more in demand. In short, a return to blush was brewing for a while and was accelerated by the pandemic, hence the rise in sales now.

During the 19th century, symptoms of tuberculosis including pale skin and red, feverish cheeks became fashionable, leading women to recreate a sickly appearance using makeup. Can you explain the link between beauty and illness, as well as how that relationship might manifest into the age of coronavirus? The mimicking of TB wasn’t a widespread or long-lasting trend because historically there is a much stronger link between beauty and health than illness. Having said that, what the recreation of tuberculosis did was simply exaggerate the already entrenched notions of beauty – pallid skin and flushed cheeks. No one was feigning smallpox, for example, because the effects of that disease were viewed as ugly and disfiguring. (And as soon as TB began to be associated with the lower classes, it quickly became unfashionable to fake it…but that’s a whole other story.) Today there are some trends such as Igari (the “hangover” look) and Byojaku (“sickly”), but they are intended to achieve a distinct kawaii aesthetic. Again, no one is doing a tutorial on getting the coronavirus look using makeup because the symptoms are viewed as unappealing (plus I’d like to think with so many lives lost people would be a little more sensitive than to pull a stunt like that.) There is a link between beauty and illness, but only so far as the illness’s effects align with current beauty standards. Overall, blush is primarily used to look healthy. For every one “hangover” or other similar trend piece, there are at least 10 articles emphasizing the importance of wearing blush while ill to counteract the symptoms that are perceived as unattractive. Sometimes a warm-toned blush or even bronzer is recommended to distract from redness or other discoloration around the nose and eyes, as that symptom is viewed as aesthetically undesirable.

Over the past year, have you noticed a shift at all in how people are wearing blush? What I’ve been observing in beauty publications and on social media is that people are perceiving blush as more than an afterthought or a basic necessity in tying a look together. Blush is becoming exciting in its own right again; cheeks are no longer playing third fiddle to eyes and lips or serving just as a canvas for contour and highlight. On a basic level, unlike the lips, at least part of the cheeks is still visible while wearing a mask. Some have adapted the ‘80s trend of taking blush up past the temples, closer to the eyes, so that it’s more noticeable behind a mask – as with eye makeup, the emphasis is on what can still be seen in a mask.

More significantly, how people are wearing blush is just one part of the pandemic’s larger impact on makeup routines more generally. People found their normal beauty routine disrupted, and they’ve been questioning it: why am I wearing makeup, who am I wearing it for, and do I really want to be wearing a full face every day? From my perspective, people seem to have gone in several directions or a combination thereof: some kept up with their usual makeup routine to retain a sense of normalcy, others began experimenting with makeup in ways they wouldn’t normally otherwise, and still others greatly pared down their routine. It’s this last path, I think, that has caused the biggest shift in how people are wearing blush. Many are finding they don’t want or feel the need to do a full face for virtual meetings and staying at home, so they’re embracing a more relaxed approach that includes a quick swipe of blush rather than combining it with contour and highlight. Sculpted cheekbones are being pushed aside in favor of a less “done”, more carefree look that is easily achieved with blush. Whether or not low-maintenance makeup sticks around as quarantine life fades away is anybody’s guess; I think it might, but I also think in some instances people will be piling on the makeup as a way to celebrate the end of the pandemic – now that our faces aren’t obscured we can wear as much as we like without a mask rubbing it off. In fact, while the average makeup wearer may be rediscovering the joys of basic blush application, over the top blush is already trending on the editorial side. If the usual amount of cheek color signifies physical well-being, in the age of COVID-19, perhaps an excessive application will reinforce the notion of health. The super flushed look may end up as an exuberant symbol of survival.