I was trying in vain to catch up on some beauty news many moons ago and came across this article at Who What Wear – yet another on the history of red lipstick. There were a lot of things that bothered me about it, but the number one offense was the doubling down on the myth of Elizabeth Arden handing out lipstick to suffragettes during a 1912 march in New York City. After recognizing this claim’s veracity was murky at best, the article’s author stated, “I wanted to know more, so I went straight to the source: Elizabeth Arden, the very same global beauty brand founded by the namesake cosmetics maven.” A brand can certainly be used as a source, provided there are legitimate historical records that serve as evidence for their claims. However, in this piece there were many statements made by Janet Curmi, VP of global education and development at Elizabeth Arden, without anything to back them up. “On November 9, 1912, 20,000 women took to the streets of New York to advocate for the right to vote. Elizabeth Arden, a dedicated suffragette herself, opened the doors of her New York spa to hand out her Venetian Lip Paste and Venetian Arden Lip Pencil, before joining the suffragettes marching down Fifth Avenue as a sign of solidarity. The most striking sight was the bold red color on the women’s lips.” The accompanying photo shows suffragettes marching at the May 4, 1912 event (not November)…with nary a one wearing visible lip color. Just for funsies I reviewed some news coverage on the November march.* As with the May march, they describe quite a few details, including the exact route and the women’s clothing, but lipstick is not among any of them.

I am very interested to know where Curmi got this information. Arden wasn’t, in fact, particularly known as a “dedicated suffragist.” The legend of her providing lipsticks to marching suffragettes goes back to at least 1999 and names the May 4 rally (see Lucy Jane Santos’s outstanding effort to unravel its history, along with my findings), so November 9 appears to be a new twist on the mythos. Another addition is the reference to Venetian Lip Paste and Pencil specifically being given to suffragettes. As far as I can tell, no particular products were mentioned in the Arden suffragette story until 2021, when author Louise Claire Johnson published a book entitled Behind the Red Door: How Elizabeth Arden’s Legacy Inspired My Coming-of-Age Story in the Beauty Industry. Johnson states that Arden provided Venetian Lip Paste and pencil to the crowds at the November march, but does not cite an exact source: “However, six months later, on November 9, 1012, Elizabeth could no longer sit idly by in silence. Shuttering the salon for the day, she took to the streets and joined 20,000 women, double the size of the previous parade, and advocated for the right to vote. The most striking sight was the bold red color on the women’s lips, as they vibrantly spoke their truth. Elizabeth weaved among the masses handing out her Venetian Lip Paste and Venetian Arden lip pencil in deep red – the original ‘lip kit’. In history, it is often the slightest gestures that become revolutionary. The red lip kits were small, yet mighty weapons – a red pout in place of a middle finger against the patriarchy. Red lips were still considered illicit and immoral, so the women wore them in unison as a rebellious emblem of emancipation. Makeup was no longer a sign of sin but of sovereignty.” (p. 63-64)

While it’s been confirmed that Arden had a line of “Venetian” skincare products by 1912, her lip makeup products were still in development. There was a Venetian Lip Salve advertised in Vogue, but I’m guessing it was a clear or slightly tinted balm and not “paint”, and I could not find any mention of Venetian Lip Paste/Pencil until 1919. Additionally, 2 pages after her claim of the paste and pencil being being handed out, Johnson seems to contradict herself by stating that “after the suffrage parade, [Arden] started introducing makeup products into her Venetian skincare line.” So if the makeup was not introduced until after the parade, how was it handed out? It’s entirely possible Arden was making a prototype of these lip items available through her salons – most likely she was mixing up limited, small batches of makeup to select clients who requested it – but no ads, trademark, etc. for Venetian Lip Paste and Lip Pencil prior to 1919 seem to exist, which leads one to believe that they were not being mass produced and able to be distributed to thousands of people. Perhaps any records relating to the origins of Venetian Lip Paste and Lip Pencil and for that matter, any records of Arden giving them out at a rally are in the mysterious “Elizabeth Arden papers”, which, as one historian explains, are scattered about across the U.S. and not readily available. Still, I find it curious that the company has never provided any documentation that Arden handed out lipstick, and specific products at that. I also reached out to Behind the Red Door’s author – twice – asking for her to clarify where she came across the story of the Venetian lip products and did not receive a reply.

Curmi further embellishes the tale by remarking that mostly because of Arden, suffragette leaders began to wear red lipstick as well. “While turn-of-the-century actresses like Sarah Bernhardt and Mary Pickford helped to bring red lipstick into vogue in 1912, it was Elizabeth Arden who gave it political power, elevating it to a symbol of rebellion and female empowerment…red lips were still considered illicit and immoral at the time, so the women wore them in unison as a rebellious emblem of emancipation and defiance. [Leaders] of feminist movements such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman began sporting red lips as a symbol of female empowerment. Since then, red lipstick has mirrored resilient femininity.” Once again, I’m going to direct you to Lucy’s article on the subject, where she points out that Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in 1902. Continuing to wear lipstick 10 years after one’s death would be quite an impressive feat, no?

Finally, anyone who has researched makeup’s rise in the early 20th century understands there were many other factors at play in terms of how lipstick and other makeup became socially acceptable. Yes, wearing obvious makeup was certainly a seismic cultural shift and viewed as rebellious, but it cannot be credited to any one person or movement. “One of the first female entrepreneurs in 20th century America, Arden remarkably turned a $6000 investment into a billion-dollar brand. She opened the Red Door Spa on Fifth Avenue in New York City in 1910 at a time when makeup and cosmetics were considered improper. She was instrumental in changing how the world thought about beauty—the ultimate influencer,” Curmi says. These statements demonstrate the pitfalls of letting a company executive guide the narrative instead of an actual historian, as a brand employee has a vested interest in presenting their business as groundbreaking rather than telling the truth. In this case, not only does Curmi offer no hard proof for the suffragette-related claim, she conveniently leaves out the contributions of other major “influencers” of the time, i.e. Helena Rubinstein, Max Factor and Madam C.J. Walker, to say nothing of smaller brands and figures, technological advances, and economic and political factors other than suffrage. Obviously these omissions make sense as her role is to promote the Arden brand and because the reporter reached out to Arden specifically and not other companies for this article, but they also make for a rather incomplete and biased snapshot of lipstick’s history.

Finally, the subject of makeup and political power is one for another time, but for the record, most early advertising marketed it as a way to better meet white supremacist beauty standards and continue enforcing compulsory heterosexuality rather than for any “empowering” purpose. Once again, nuance is wholly neglected in favor of pushing a feel-good story that serves primarily to buoy a company’s reputation.

I’m ending this post with several requests. For journalists, one: if you must interview brand representatives, please do not rely on them as a credible source for the stories you’re trying to get to the bottom of, unless they furnish documentation from the company’s archives or other legitimate pieces of evidence. Otherwise your article runs the risk of resembling a glorified ad rather than journalism. Two: please choose another makeup topic to cover besides red lipstick (or at least, an angle not focused on cis-het white women’s history). Maybe red lipstick’s fame and status as a “classic” means stories about it get more clicks, but makeup history is so incredibly varied and rich, many other subjects would be of interest to the general public. The last plea I’m making is for the Elizabeth Arden company to show the world a shred of historical evidence that their founder provided lipsticks to suffragettes. We’re still waiting.

*These were all from the New York Times: “400,000 Cheer Suffrage March,” Nov. 10 1912, p. 1; “New States to Lead in Suffrage Parade: Army of 20,000 Expected to Participate in Fifth Avenue Procession,” Nov. 9 1912, p. 22; “Torches in Hair to Guide Parade: Electric Novelties Planned for Tomorrow’s Big Suffrage Demonstration,” Nov. 8 1912, p. 7.

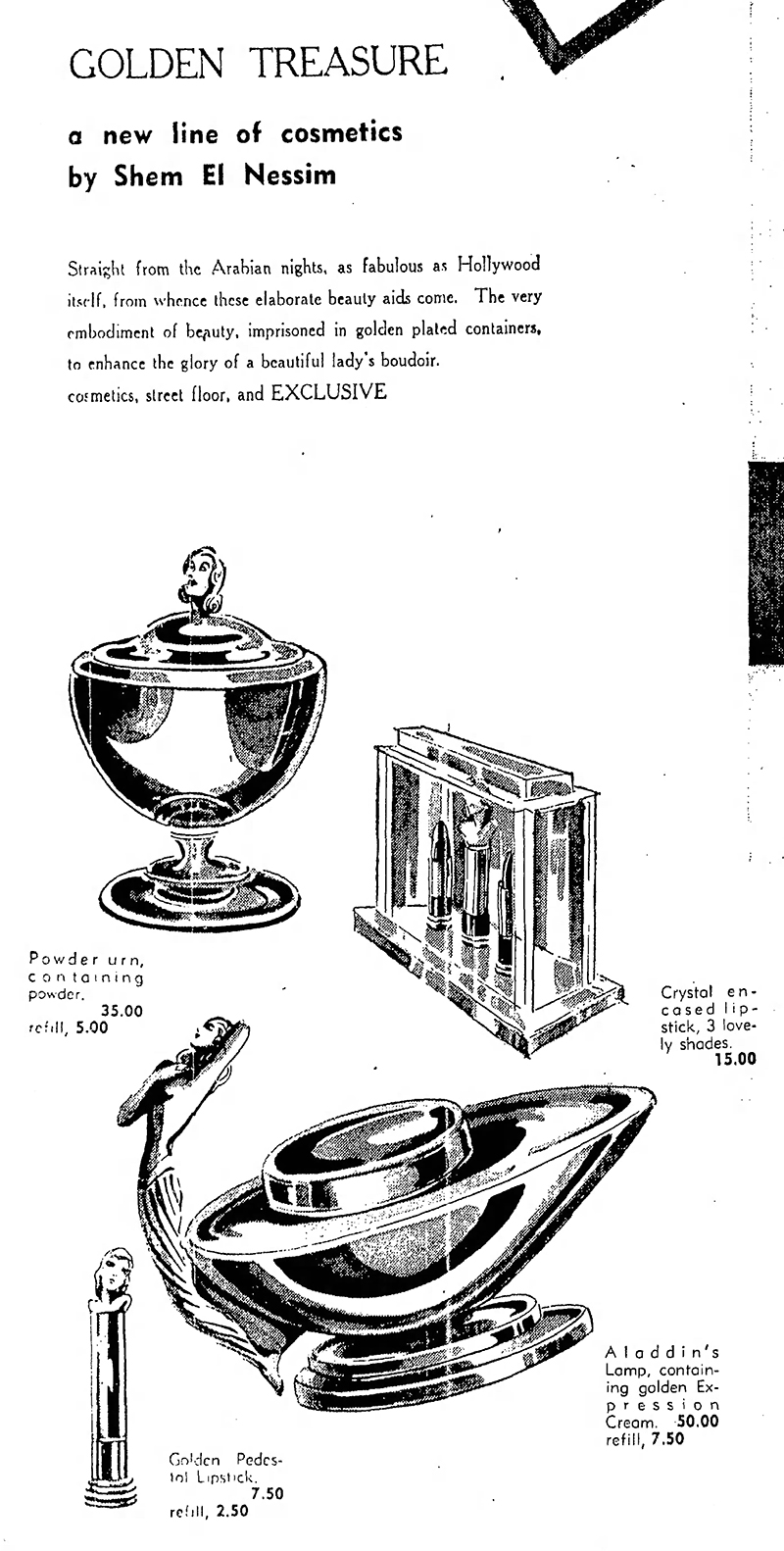

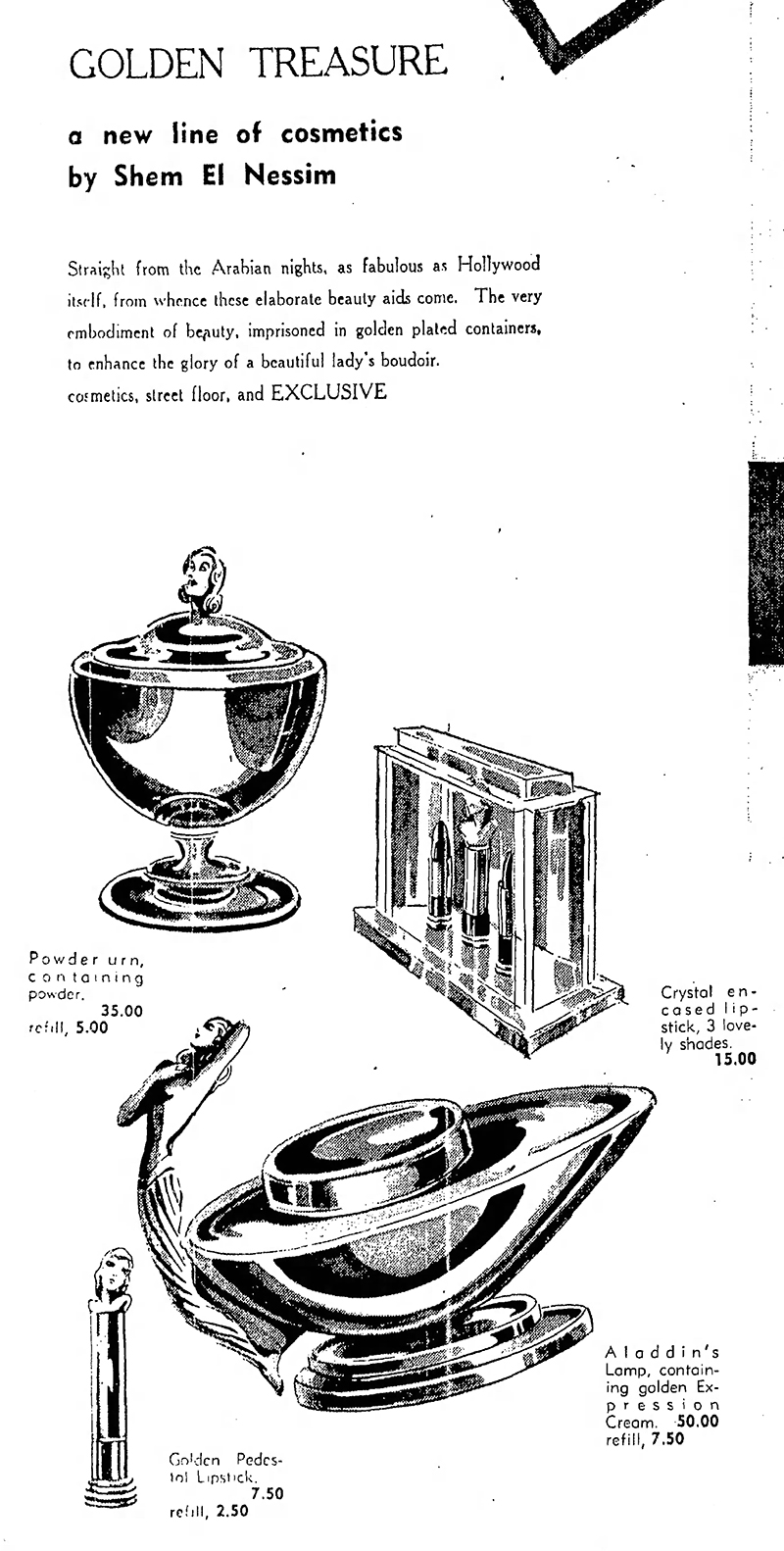

Today the Museum is featuring a flash-in-the-pan brand from the 1940s. Shem el Nessim was a very short-lived line, lasting only about 6 months during the second half of 1946. I couldn’t find much info, but one thing I can say is that it’s not related to the fragrance of the same name by British perfumer Grossmith. The collection consisted of a lipstick (six shades), lipstick set with 2 refills, face powder, and a face cream. All were advertised as being plated in 14kt gold.

Let’s talk about the cultural appropriation aspects first. Shem el Nessim appears to be an incorrect, or at least outdated, spelling of Sham el Nessim, a roughly 5,000 year old Egyptian festival/holiday that is celebrated the day after Orthodox Easter (which, this year is today…yes, I’ve been planning this post for a while). The day marks the beginning of spring and is accompanied by several traditions, including dyeing eggs and enjoying picnics and other outdoor activities. Shem el Nessim loosely translates to “smelling the breeze”. Why Grossmith spelled Shem with an “e” is beyond me, but it seems this new brand did too. And while Grossmith engaged in cultural appropriation to market this fragrance and others, they came relatively close to understanding the holiday and translating it correctly. The Shem el Nessim cosmetics line, meanwhile, claimed it was Arabic for “bloom of youth,” which is totally off. Also, the name of one of the three lipstick shades appears to be nonsense. “Garfoz” does not seem to be an actual word in any language.

Next, the face cream container is shaped like an “Aladdin lamp”?! No information turned up about the brand’s founder, but I’m going to go out on a limb and say that Shem el Nessim was started by a white American who wanted to capitalize on Western fantasies of the “exotic” Middle East. It’s certainly an eye-catching design for a face cream , but completely inappropriate for a brand with no roots in or discernible connection to Egyptian or Middle Eastern heritage. Not to mention that if the entire jar was filled, it would be cumbersome to dig out product from the pointy front part of it. What’s even weirder is the attempt to connect the ancient Middle East to modern-day Hollywood, where the company was headquartered (8874 Sunset Blvd, to be precise.)

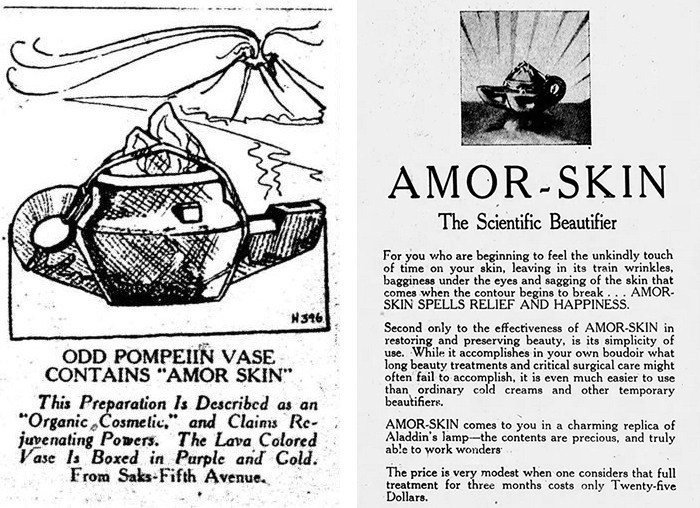

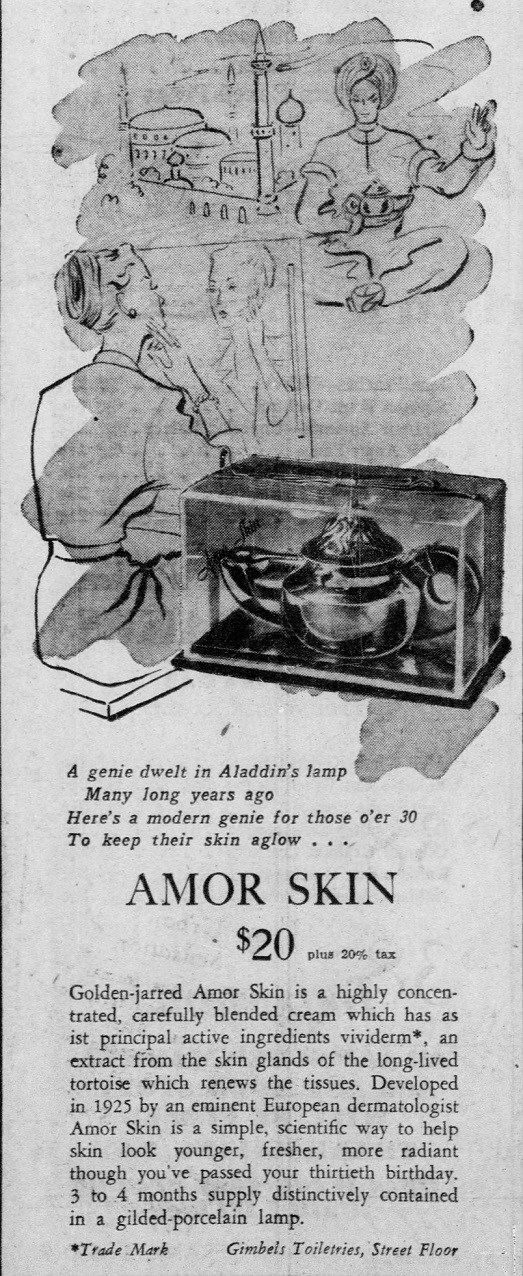

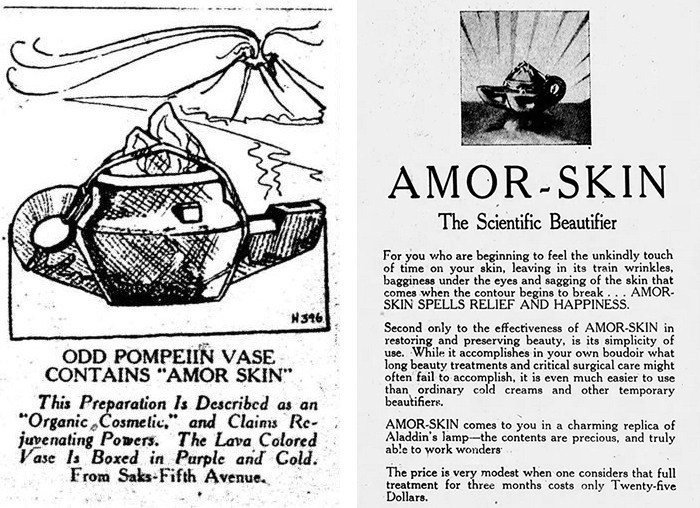

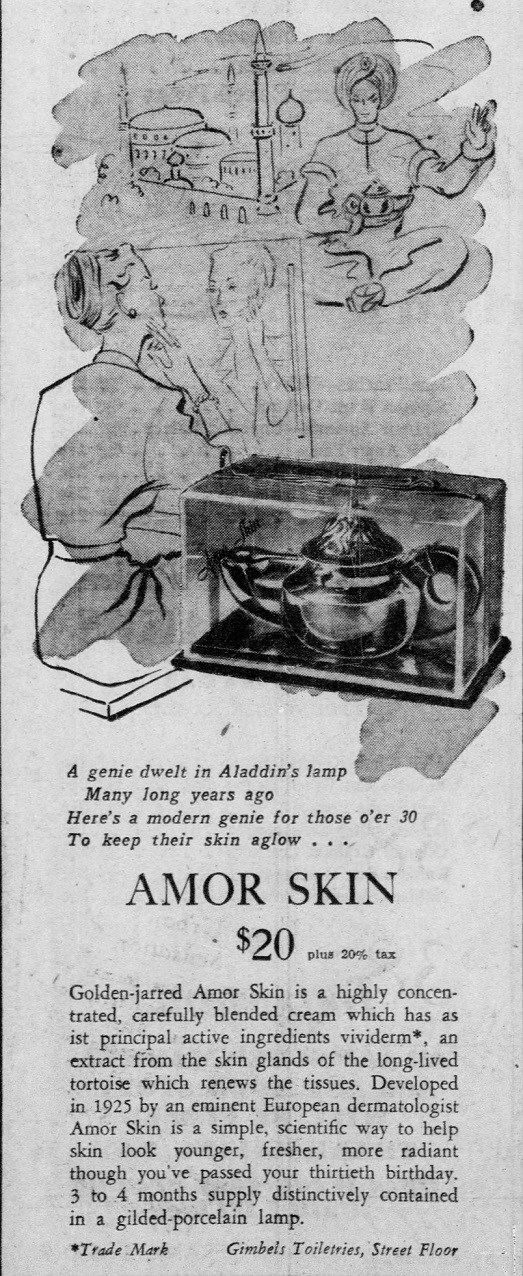

In addition to using an existing product name, Shem el Nessim may have been looking at Amor Skin’s lamp-shaped face cream, which debuted in 1927. It seems Amor Skin’s lamp was originally a “Pompeiian” design, but by 1929 they were largely marketing it as an Aladdin Lamp.* Additionally, in the fall of 1946 Amor Skin heavily increased their advertising for the lamp and emphasized the Aladdin aspect, perhaps as a direct response to Shem el Nessim. Of course, the uptick in advertising may have been a simple coincidence, as Amor Skin had just returned to the market in the fall of 1946 after temporarily shutting down production during the war.

According to an October 1946 article in WWD, the collection, or at least the lamp, was allegedly designed by a “Viennese sculptor” named Peticolas. After a fairly exhaustive search, it seems this artist did not exist. There was a Sherry (Sherman) Peticolas who lived in L.A. and was active in the 1930s-40s, but as far as I know he was American, not Austrian. Additionally, his style was markedly different from the pieces in the Shem el Nessim line, and I couldn’t find a record of Peticolas designing cosmetics.

(image from commons.wikimedia.org)

So while it’s certainly possible Peticolas was involved in the design, there’s no concrete evidence to confirm. As of July 1946 Shem el Nessim had hired advertising agency Klitten and Thomas, so I’m wondering if the claims about the meaning of Shem el Nessim and the Peticolas design in the ad copy were entirely their doing. In any case, there doesn’t seem to be any mention of Shem el Nessim after December 1946. I’m guessing Grossmith put a stop to the company very quickly, as the Shem el Nessim fragrance was most likely trademarked, and perhaps Amor Skin also told them to back off. Or it could have happened in the reverse: Shem el Nessim’s owner(s) were unaware of either the Grossmith fragrance or Amor Skin lamp when creating the line, quickly realized their missteps and abandoned the business. What’s interesting is that the Shem el Nessim Sales Co. did not seem to change names, they simply disappeared. Oh, if only all businesses that ripped off existing brand names (knowingly or not) would go away forever…the world would be much better off, yes? I also suspect the price points for a fledgling brand that was not an offshoot of a fashion/perfume house or other well-known entity were too high. A more established brand, or one started by a big fashion name or celebrity might have had better luck charging the 2022 equivalent of $110 for a lipstick. Per the ad copy, Shem el Nessim was intended to be “exclusive” and not mass market, but that may not have been a profitable tactic to start with.

Cultural appropriation and unoriginal name aside, the Shem el Nessim lipstick case remains a unique specimen of makeup design. The style recalls both classical busts and Surrealist art, with a dash of Camille Claudel in the graceful tilt of the head, dreamy, far-away expression and rendering of the hair. It could also be considered a more sophisticated and artistic precursor to the doll-shaped lipsticks that would prove popular some 15-20 years later.

Finally, while I haven’t seen actual photos of the other items, the lipstick looks to be the most elegant, albeit impractical, design – certainly more visually appealing than the powder urn (the poor woman looks decapitated) and lamp (overtly culturally appropriative and the figure’s silhouette and pose are a bit tacky).

Thoughts? If anyone can contribute any other information on this brand I’m all ears. 🙂

*While nearly all of the newspaper ads between 1946 and 1950 referred to the Amor Skin lamp as Aladdin’s, a handful of them along with the November 1946 issue of Drug and Cosmetic Industry used the previous Pompeiian description.

I have so many other books I'd like to review but so little time, and this tome had been sadly collecting dust on my nightstand for ages, so here's a quick review for a quick read.* Lipstick: A Celebration of the World's Favorite Cosmetic by Jessica Pallingston was released in 1998, just a few months prior to Meg Cohen's Read My Lips: A Cultural History of Lipstick which I reviewed in 2015 and vowed to compare it to Pallingston's book shortly thereafter (in other words, I'm a mere 5 years overdue for that task. Sigh.) Anyway, I found the two books to be more or less the same in terms of content. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but I think if you were looking for a basic history of lipstick you could choose one or the other and not feel like you're missing out.

The introduction left a bit to be desired, as it placed emphasis on lipstick as a tool to either "empower" women or lure men; there was no mention of playing with color as a means of self-expression. I also think, as I did with Cohen's intro, that the fetishization of lipstick and the overblown description of its alleged power were a bit much. Lipstick can be life-changing, yes, but proclamations like "Lipstick is a primal need" made me roll my eyes.

Like Cohen's book, the first chapter is a brief overview of the cultural significance of lipstick throughout history, starting with ancient times and ending with the 1990s. Not a bad summary, but since I've been doing this a long time there was little earth-shattering news. This isn't the author's fault, however, as the book was released over 20 years ago so this sort of information wasn't as ubiquitous as it is now. Containing the standard tidbits about ancient Greek prostitutes and the patriotic duty lipstick served during World War II, the chapter is a tidy summation of how lipstick was worn through the ages. But the section on the '90s penchant for brown lipstick nearly made my eyes pop out of my head, as I had never come across theories about why brown lipstick (and brown in general) was so popular. This will definitely inform my research for my '90s beauty history book!

Chapter 2 presents no fewer than 14 theories outlining why lipstick wields more impact than other cosmetics. I found them to be slightly lacking, as I believe the "lipstick as phallic object" or "painted lips mimicking sexual arousal" theories rather tired at this point, not to mention sexist. Ditto for the idea that children feel more protected if their mother leaves a lipstick print as they kiss them goodbye before school, lipstick application as oral fixation, or as a rite of passage for teenage girls. There was some truth to the theory about lipstick as a sort of armor or camouflage, but seeing no mention of how lipstick fits into the larger notion of makeup as a means of self-expression was disappointing. And I would have liked to see more about makeup's transformational power, but the only theory about lipstick as metamorphosis came in the form of fairy tales, i.e. one's wildest dreams come true through makeup and one will magically become "pretty" if they wear it: "When I put on lipstick I am as pretty as Cinderella" was one of the quotes included. (Why is the author quoting a literal 5 year-old?)

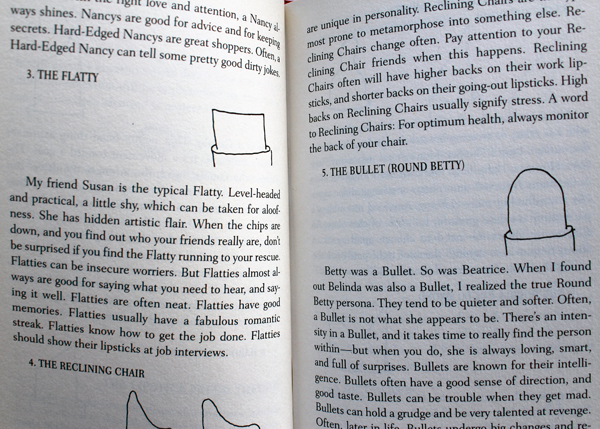

Chapter 3, appropriately titled Lipstick Freud, delves into pop psychology as Pallingston takes us through the various lipstick shapes that are the result of one's unique wear pattern (which obviously also depends on the shape of one's lips), along with what various application methods say about the user and something called lip reading. Much like astrology and palm reading, they're fun but not necessarily accurate or based on hard scientific data.

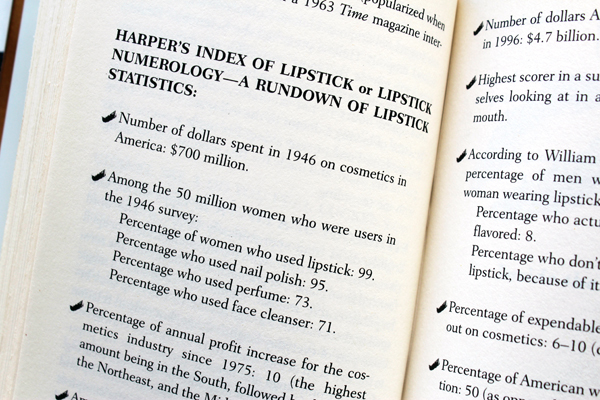

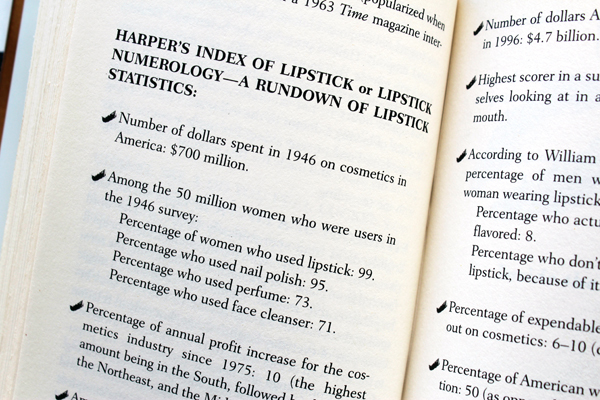

Chapter 4 was my favorite, as it provided a list of bite-sized anecdotes about lipstick as well as a lipstick-by-the-numbers section. I miss Allure's by-the-numbers feature tremendously and am dying to include something similar in exhibitions.

Chapter 5 gets into the nitty gritty of lipstick – the complete process of how it's produced and a lengthy list of ingredients, which is good information to have on hand. This chapter also includes sections on colors and names, both of which I believe warrant their own books. (There is actually an entire book on red lipstick, which I hope to review sometime this year.) You can definitely see how times have changed, since black and grey aren't mentioned at all and blue and green are discussed as having solely negative connotations of illness or death. These can be accurate, mind you, but as someone who has now fully embraced non-traditional lipstick colors (especially grey – I own no fewer than 9 shades), I found myself chuckling at the idea that blue or green lip colors used to be mostly associated with bad health. There are incredibly vibrant blue and green shades on the market these days – what could possibly be more a reminder of rebirth and growth than something like Menagerie's Juniper lipstick, for example, or capture the vitality of a hot summer day like MAC's Blue Bang? Anyway, while it was a nice read, it may have been good to include a section on different lipstick finishes and textures. But once again, this is really just part and parcel of this book being released in 1998, when liquid and glitter lipsticks weren't absolutely everywhere.

The naming section was notable for its inclusion of shade names from Renaissance England: apparently Beggar's Grey, Rat and Horseflesh were all listed as lipstick colors.

Chapter 6 gives some tips on how to navigate choosing and buying a lipstick in-store. With the advent of online shopping and swatches, this is largely obsolete and the advice itself was pretty basic. One unusual tip was to try swatching a lipstick on the inner wrist. I'm personally a fan of trying colors on fingertips since they are allegedly closer to your natural lip color, but if you want to find out how the color will look next to your overall facial skintone, the wrist is the place to swatch. Chapter 7 was more of the same, a list of lipstick application and color-coordination techniques that aren't anything you couldn't find online or in any beauty magazine.

Chapter 8 is probably the only chapter that is not in need of a major update, as it provides recipes for making your own lipstick that are still totally doable today. Even as technology and customization options evolve, there will always be a subset of the population who like to DIY their lipstick for various reasons – ingredient preferences, cost, or just because they like experimenting. Chapter 9 continued with recipes, but they were really intended more as a joke to show what people did throughout history to make lipstick. "From the medieval glamour guides, here's a recipe for making lipstick at home: Go outside. Get a root. Dry it. Pulverize it. Add some sheep fat and whiteners to get desired color. If you are upper class, go for a bright pink. If lower class, use a cheaper earth red. If you are having trouble being pale, and have the money to pay for it, get yourself bled. If you're alive during the Crusades, wait for the Crusaders to come back, as they'll bring some glamorous and exotic dyes, ointments and spices, and you'll be able to experience the makeup golden age of the Middle Ages." LOL.

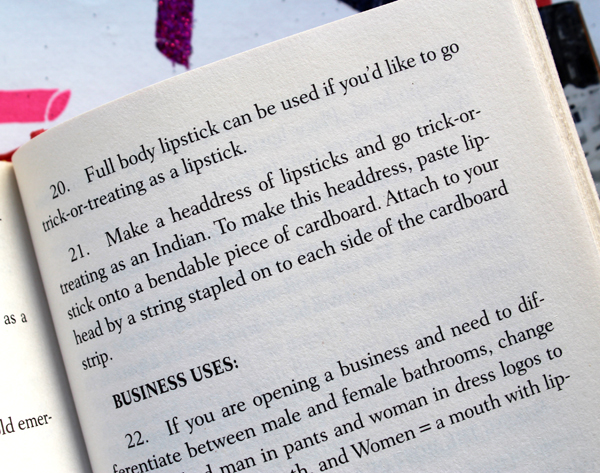

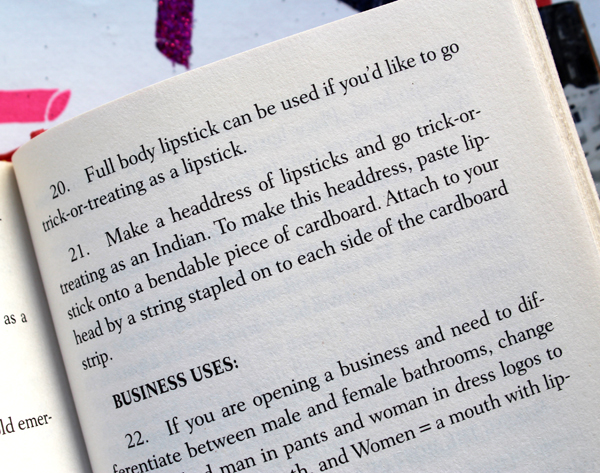

Chapter 10 was a mishmash of suggestions for alternative uses of lipstick and a list of famous art history and pop culture lipstick moments. Most of the suggestions were good ideas, but some, like no. 21, made me cringe. Yikes.

But I did love all the artist references, for they included two I plan on writing about for Makeup as Muse (Rachel Lachowitz and Sylvie Fleury) and Claes Oldenburg's Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks which I covered back in October. The final chapter (if you can even call it that, as it's only a page and a half) sings the praises of lipstick yet again, and honestly, probably wasn't necessary.

Overall, Lipstick is a nice book for those in need of a primer on lipstick, but if you're in the mood for something more academic or a thorough feminist analysis of lipstick, this is not it. As noted previously, if you're looking to purchase a book on lipstick history I would go with either this or Read My Lips, but I don't think both are necessary for a beauty library (unless you're like me, who obsessively hoards makeup books in addition to makeup itself). Lipstick has sound sources, although by now they are a bit dated and I believe are mostly the same as Cohen's. I will say that the advantage of Cohen's book over Pallington's is the inclusion of photos, which were non-existent in Lipstick. So it just depends on whether you want a glossier tome with more eye candy or one with less visual frills and more anecdotes, as the information in both is basically identical.

Have you read this one? I'm really hoping someone will write an updated cultural history of lipstick, as after reading this I think one is sorely needed.

*Another reason I chose to review this book first instead of the others I have planned is that I was recently interviewed by a journalist who is writing a brand spankin' new cultural history of lipstick, so hopefully in the next year or so we will have an updated version (and hopefully I will be quoted!) Stay tuned. 😉