In an effort to condense a few posts I'm doing some quick reviews of recent additions to the Museum's library. Hopefully they'll be of use…I mean, they can't be any worse than my usual long-form reviews, right?

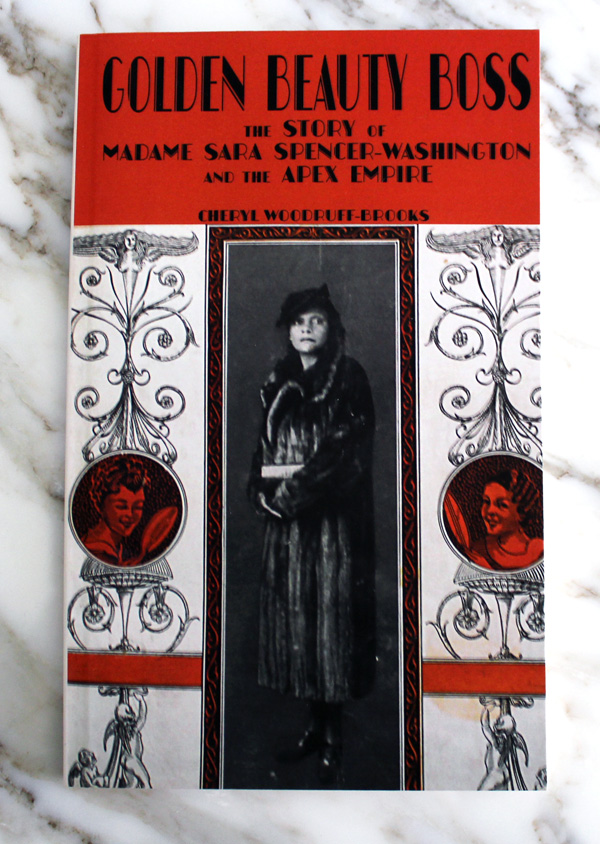

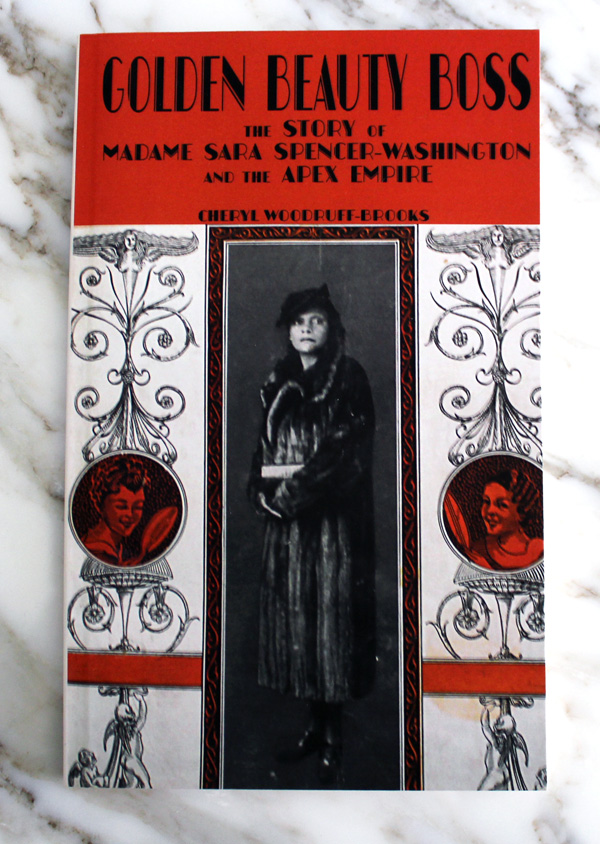

Up first is historian Cheryl Woodruff-Brooks's biography of Sara Spencer Washington, who established the Apex News and Hair Company in 1919. Over the years the company expanded to include 11 Apex Beauty Colleges in the U.S. (including one right here in Baltimore – more on that later!) and abroad, Apex Laboratories to manufacture hair care, cosmetics and even household goods, and Apex News, which produced publications for her estheticians and sales agents. The Apex empire, as it came to be known, employed roughly 45,000 sales agents at its peak. Madame Washington wasn’t just a savvy entrepreneur; she regularly gave back to the Black community by offering scholarships to Apex schools, establishing a golf course that welcomed people of all races and economic status, and even founded a nursing home, Apex Rest. Golden Beauty Boss: The Story of Madame Sara Spencer-Washington and the Apex Empire is relatively short but incredibly informative. I can only imagine how many hours the author spent digging through various archives.

Quality research and an intriguing story about one of the most successful Black entrepreneurs in history is a must-have for well, anyone! You can buy it here.

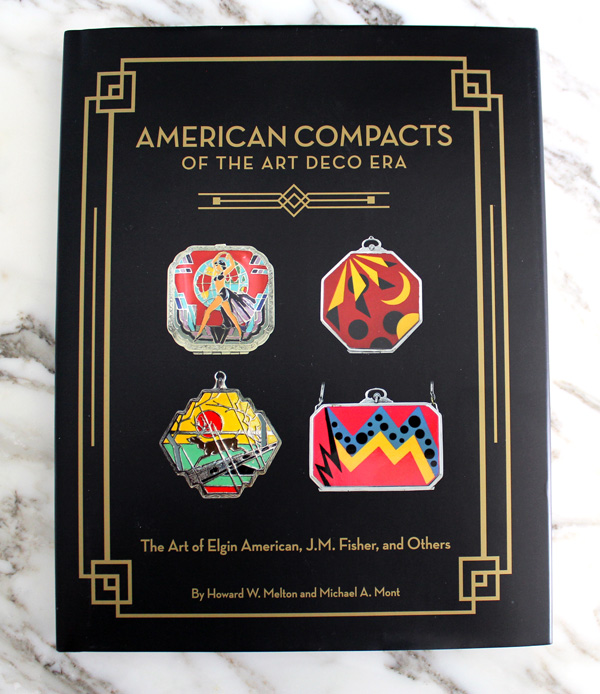

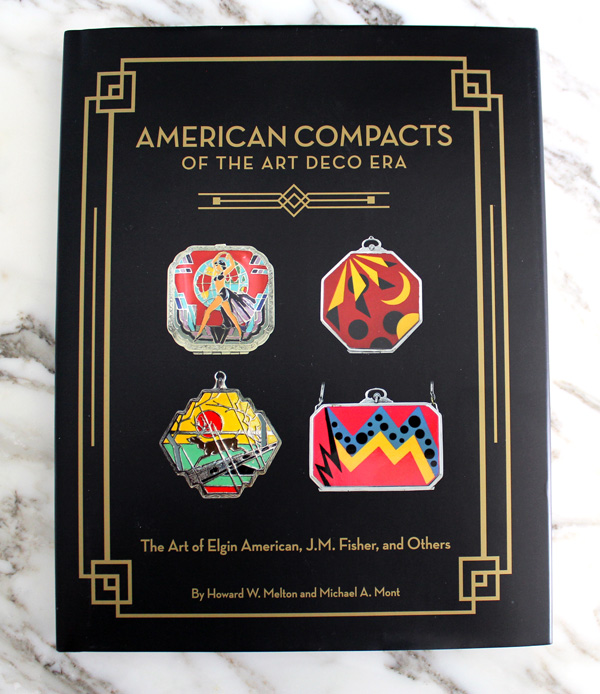

Next we have Howard Melton's and Michael Mont's American Compacts of the Art Deco Era: The Art of Elgin American, J.M. Fisher, and Others. This isn't a collector's guide; it's more along the lines of Jean-Marie Martin Hattemberg's tomes on powder boxes and lipsticks in that there are many images of beautiful objects to drool over with some wonderful history along the way. It also includes a good amount of ads, which are very helpful in identifying compacts – of course, you can also see some Elgin compact catalogs over at the Elgin History Museum archives.

What I love about American Compacts is that it focuses on the compacts of a particular era and country so it's not overwhelming, yet still provides useful information throughout. The story of Elgin's Bird in Hand compact is a particularly great highlight. Overall, American Compacts is a necessity for the vintage makeup collector or anyone with an interest in Art Deco design. As for purchasing, you remember my interview with Andra of Lady-A Antiques, right? Well, she's offering this book at a reduced price at her store, so be sure to buy it there!

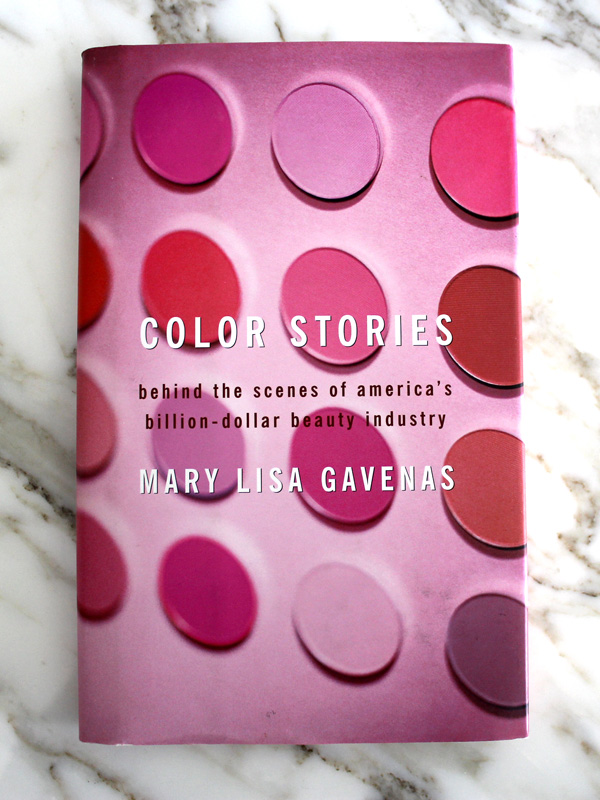

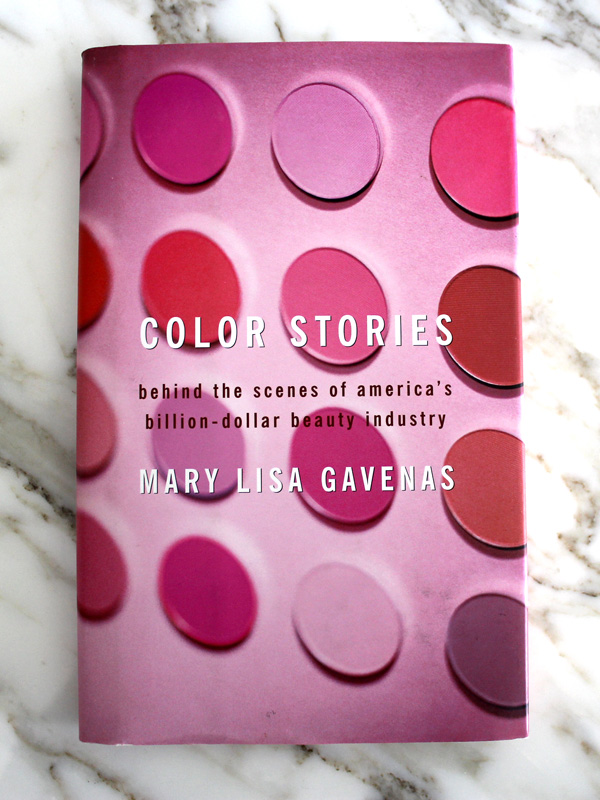

Moving along, I read Color Stories: Behind the Scenes of America's Billion Dollar Beauty Industry by journalist Mary Lisa Gavenas. It's a bit dated at this point since it was published in 2002, but still a good read as it provides a very fascinating behind-the-scenes, soup-to-nuts description of how makeup color stories were selected and marketed each season during the 1990s and early 2000s – essentially a full, unbiased story of the process.

It's very useful for anyone looking for cosmetic marketing history as well as '90s makeup history (ahem), but I think it would also be interesting for fashion or business historians more generally. I would dearly love to see an update for the age of social media, Millennials/Gen Z'ers and the increased demand for diversity and inclusion among beauty consumers. So much has changed in 20 years!

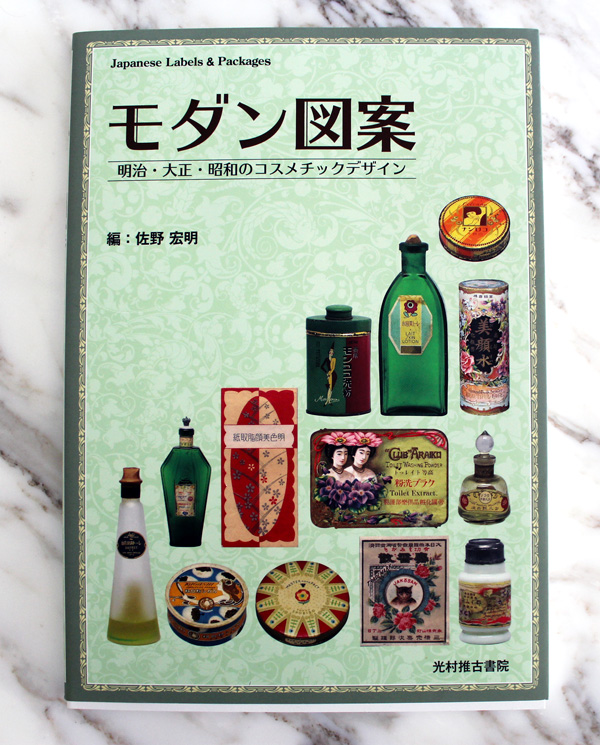

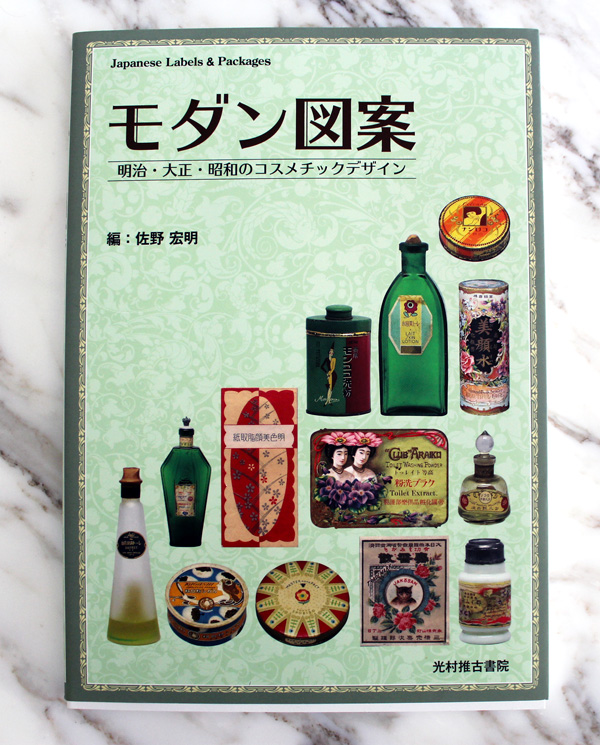

Next up is another drool-worthy book I found on ebay. It's in Japanese so I can't actually read any of the text, but the photos are more than worth it. You'll find lots of vintage Shiseido and other Japanese brands along with a sprinkling of Western lines such as L.T. Piver packaged for the Japanese market. While powder boxes, skincare and perfume comprise most of the objects, there's also personal hygiene products like deodorant and tooth powder.

If you love vintage powder boxes, vintage design and typography, or Japanese culture in general, this belongs on your book shelf. I'm keeping my fingers crossed for an English version so I can read the history behind some of the brands that are covered.

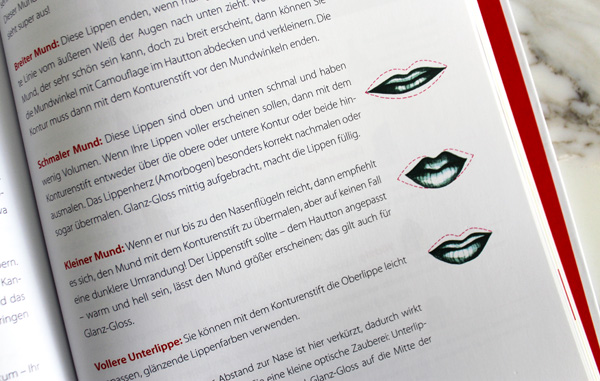

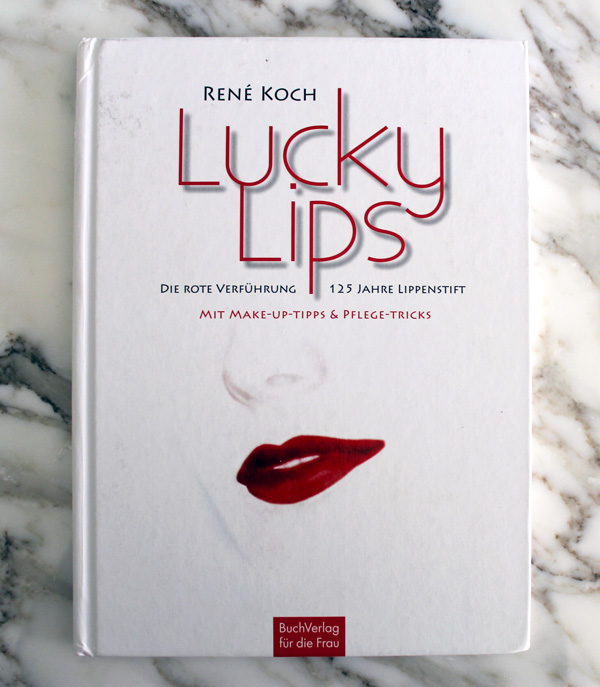

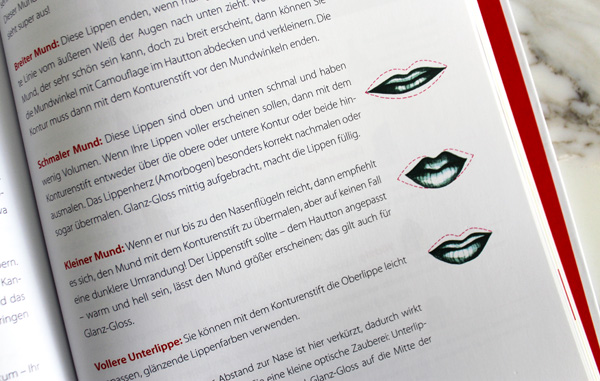

Finally, there's Lucky Lips: Stories About Lipstick, written by René Koch (a.k.a. the founder of the Lipstick Museum.) When I purchased the book I mistakenly thought it had English text alongside the German. Oops. Still, it's a nice supplement to Jean-Marie Martin-Hattemberg's Lips of Luxury as it contains different vintage lipsticks, some of which I hadn't seen before.

I wish I could compare the information offered in both books, but at the very least I can tell that Lucky Lips has some tips on lipstick application and 20th century lipstick history organized by decade. Overall, it's good to have on hand and a quality addition to the vintage makeup collector's library, especially if you can read German. (I've said this before, but if I could have any superpower it would be fluency in all languages within a matter of minutes.) If you had to choose between this one and Lips of Luxury, however, I'd go with the latter as it's a bit more extensive.

Are you interested in any of these? What books, beauty-related or otherwise, have you finished recently?

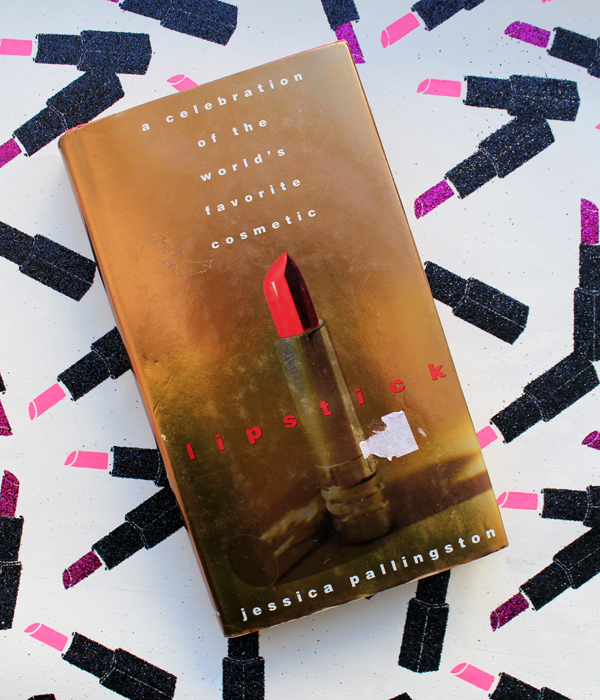

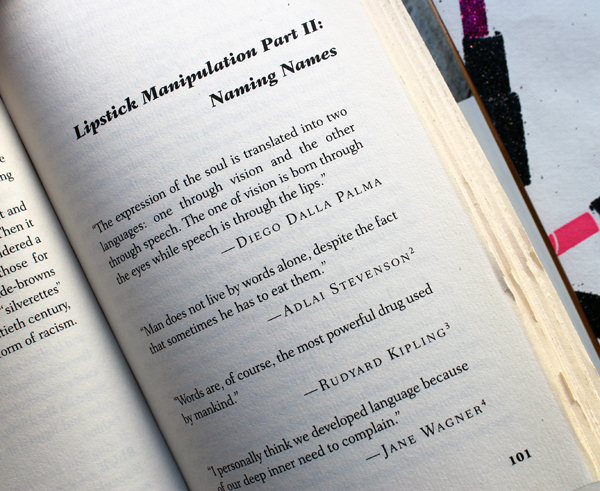

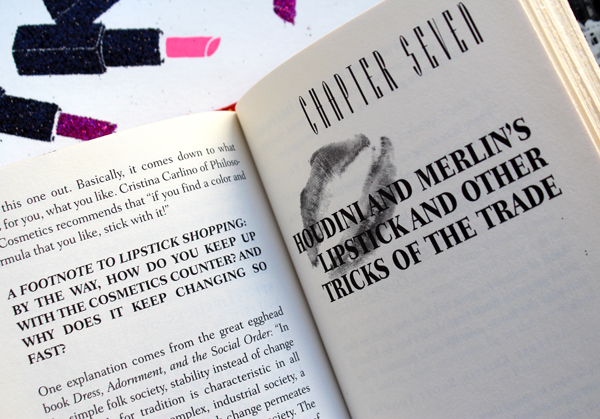

I have so many other books I'd like to review but so little time, and this tome had been sadly collecting dust on my nightstand for ages, so here's a quick review for a quick read.* Lipstick: A Celebration of the World's Favorite Cosmetic by Jessica Pallingston was released in 1998, just a few months prior to Meg Cohen's Read My Lips: A Cultural History of Lipstick which I reviewed in 2015 and vowed to compare it to Pallingston's book shortly thereafter (in other words, I'm a mere 5 years overdue for that task. Sigh.) Anyway, I found the two books to be more or less the same in terms of content. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but I think if you were looking for a basic history of lipstick you could choose one or the other and not feel like you're missing out.

The introduction left a bit to be desired, as it placed emphasis on lipstick as a tool to either "empower" women or lure men; there was no mention of playing with color as a means of self-expression. I also think, as I did with Cohen's intro, that the fetishization of lipstick and the overblown description of its alleged power were a bit much. Lipstick can be life-changing, yes, but proclamations like "Lipstick is a primal need" made me roll my eyes.

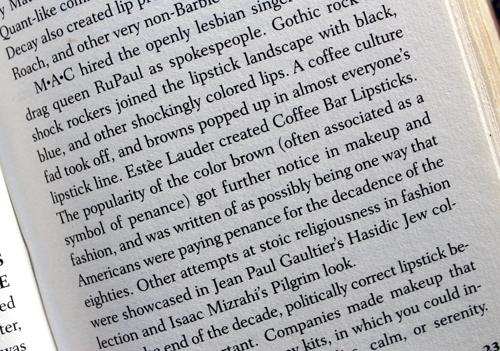

Like Cohen's book, the first chapter is a brief overview of the cultural significance of lipstick throughout history, starting with ancient times and ending with the 1990s. Not a bad summary, but since I've been doing this a long time there was little earth-shattering news. This isn't the author's fault, however, as the book was released over 20 years ago so this sort of information wasn't as ubiquitous as it is now. Containing the standard tidbits about ancient Greek prostitutes and the patriotic duty lipstick served during World War II, the chapter is a tidy summation of how lipstick was worn through the ages. But the section on the '90s penchant for brown lipstick nearly made my eyes pop out of my head, as I had never come across theories about why brown lipstick (and brown in general) was so popular. This will definitely inform my research for my '90s beauty history book!

Chapter 2 presents no fewer than 14 theories outlining why lipstick wields more impact than other cosmetics. I found them to be slightly lacking, as I believe the "lipstick as phallic object" or "painted lips mimicking sexual arousal" theories rather tired at this point, not to mention sexist. Ditto for the idea that children feel more protected if their mother leaves a lipstick print as they kiss them goodbye before school, lipstick application as oral fixation, or as a rite of passage for teenage girls. There was some truth to the theory about lipstick as a sort of armor or camouflage, but seeing no mention of how lipstick fits into the larger notion of makeup as a means of self-expression was disappointing. And I would have liked to see more about makeup's transformational power, but the only theory about lipstick as metamorphosis came in the form of fairy tales, i.e. one's wildest dreams come true through makeup and one will magically become "pretty" if they wear it: "When I put on lipstick I am as pretty as Cinderella" was one of the quotes included. (Why is the author quoting a literal 5 year-old?)

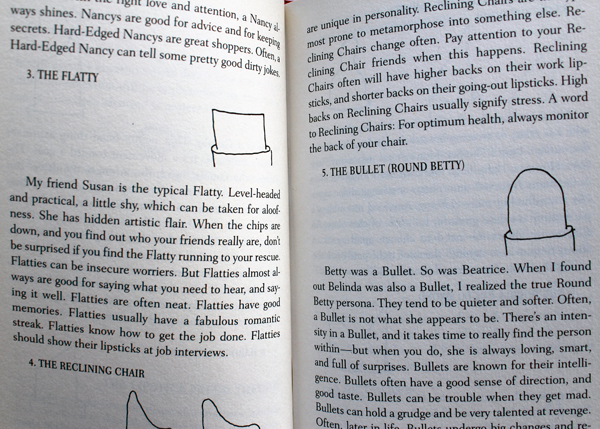

Chapter 3, appropriately titled Lipstick Freud, delves into pop psychology as Pallingston takes us through the various lipstick shapes that are the result of one's unique wear pattern (which obviously also depends on the shape of one's lips), along with what various application methods say about the user and something called lip reading. Much like astrology and palm reading, they're fun but not necessarily accurate or based on hard scientific data.

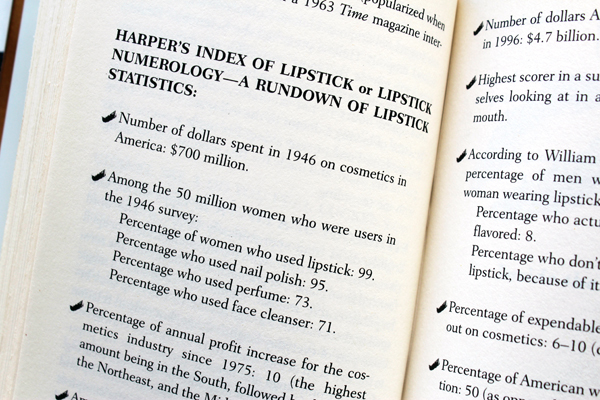

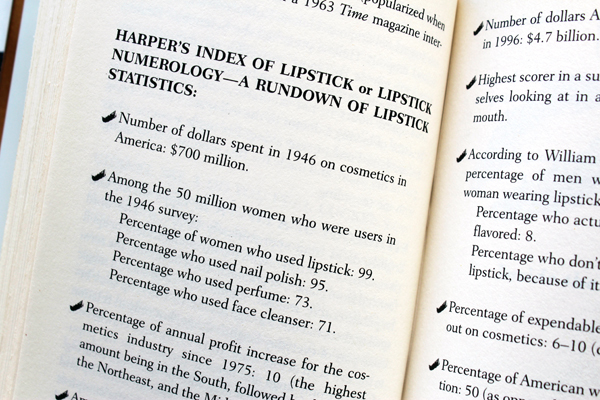

Chapter 4 was my favorite, as it provided a list of bite-sized anecdotes about lipstick as well as a lipstick-by-the-numbers section. I miss Allure's by-the-numbers feature tremendously and am dying to include something similar in exhibitions.

Chapter 5 gets into the nitty gritty of lipstick – the complete process of how it's produced and a lengthy list of ingredients, which is good information to have on hand. This chapter also includes sections on colors and names, both of which I believe warrant their own books. (There is actually an entire book on red lipstick, which I hope to review sometime this year.) You can definitely see how times have changed, since black and grey aren't mentioned at all and blue and green are discussed as having solely negative connotations of illness or death. These can be accurate, mind you, but as someone who has now fully embraced non-traditional lipstick colors (especially grey – I own no fewer than 9 shades), I found myself chuckling at the idea that blue or green lip colors used to be mostly associated with bad health. There are incredibly vibrant blue and green shades on the market these days – what could possibly be more a reminder of rebirth and growth than something like Menagerie's Juniper lipstick, for example, or capture the vitality of a hot summer day like MAC's Blue Bang? Anyway, while it was a nice read, it may have been good to include a section on different lipstick finishes and textures. But once again, this is really just part and parcel of this book being released in 1998, when liquid and glitter lipsticks weren't absolutely everywhere.

The naming section was notable for its inclusion of shade names from Renaissance England: apparently Beggar's Grey, Rat and Horseflesh were all listed as lipstick colors.

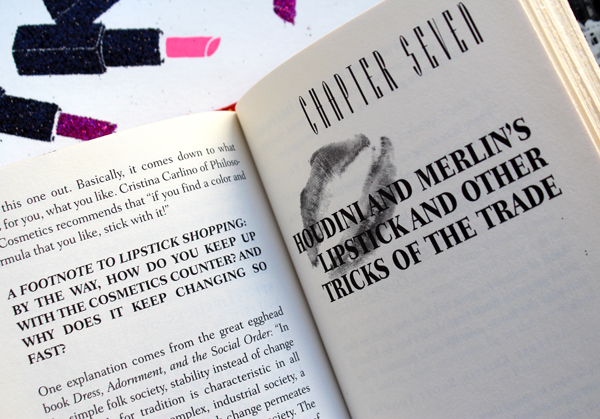

Chapter 6 gives some tips on how to navigate choosing and buying a lipstick in-store. With the advent of online shopping and swatches, this is largely obsolete and the advice itself was pretty basic. One unusual tip was to try swatching a lipstick on the inner wrist. I'm personally a fan of trying colors on fingertips since they are allegedly closer to your natural lip color, but if you want to find out how the color will look next to your overall facial skintone, the wrist is the place to swatch. Chapter 7 was more of the same, a list of lipstick application and color-coordination techniques that aren't anything you couldn't find online or in any beauty magazine.

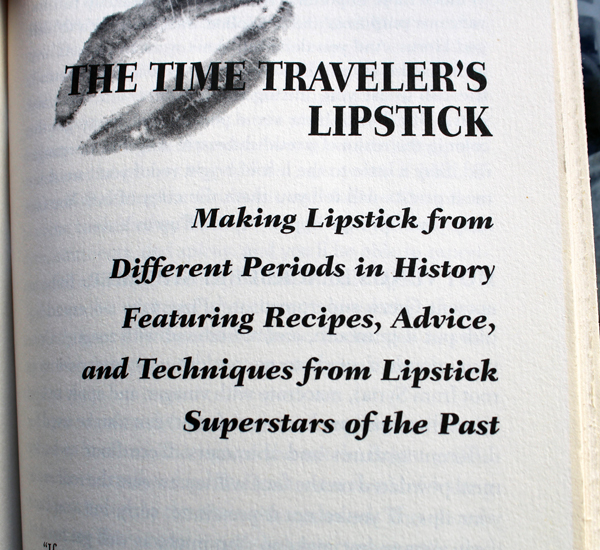

Chapter 8 is probably the only chapter that is not in need of a major update, as it provides recipes for making your own lipstick that are still totally doable today. Even as technology and customization options evolve, there will always be a subset of the population who like to DIY their lipstick for various reasons – ingredient preferences, cost, or just because they like experimenting. Chapter 9 continued with recipes, but they were really intended more as a joke to show what people did throughout history to make lipstick. "From the medieval glamour guides, here's a recipe for making lipstick at home: Go outside. Get a root. Dry it. Pulverize it. Add some sheep fat and whiteners to get desired color. If you are upper class, go for a bright pink. If lower class, use a cheaper earth red. If you are having trouble being pale, and have the money to pay for it, get yourself bled. If you're alive during the Crusades, wait for the Crusaders to come back, as they'll bring some glamorous and exotic dyes, ointments and spices, and you'll be able to experience the makeup golden age of the Middle Ages." LOL.

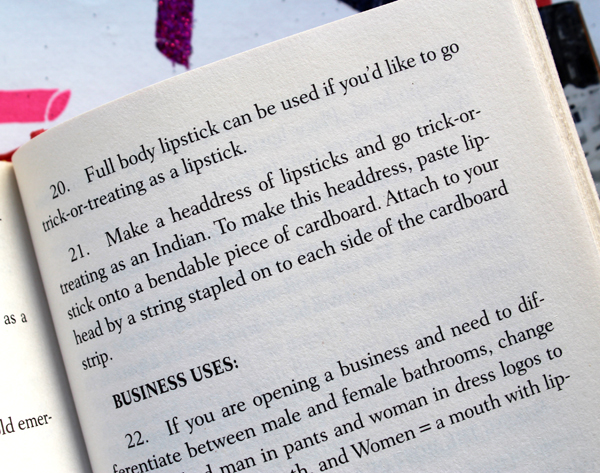

Chapter 10 was a mishmash of suggestions for alternative uses of lipstick and a list of famous art history and pop culture lipstick moments. Most of the suggestions were good ideas, but some, like no. 21, made me cringe. Yikes.

But I did love all the artist references, for they included two I plan on writing about for Makeup as Muse (Rachel Lachowitz and Sylvie Fleury) and Claes Oldenburg's Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks which I covered back in October. The final chapter (if you can even call it that, as it's only a page and a half) sings the praises of lipstick yet again, and honestly, probably wasn't necessary.

Overall, Lipstick is a nice book for those in need of a primer on lipstick, but if you're in the mood for something more academic or a thorough feminist analysis of lipstick, this is not it. As noted previously, if you're looking to purchase a book on lipstick history I would go with either this or Read My Lips, but I don't think both are necessary for a beauty library (unless you're like me, who obsessively hoards makeup books in addition to makeup itself). Lipstick has sound sources, although by now they are a bit dated and I believe are mostly the same as Cohen's. I will say that the advantage of Cohen's book over Pallington's is the inclusion of photos, which were non-existent in Lipstick. So it just depends on whether you want a glossier tome with more eye candy or one with less visual frills and more anecdotes, as the information in both is basically identical.

Have you read this one? I'm really hoping someone will write an updated cultural history of lipstick, as after reading this I think one is sorely needed.

*Another reason I chose to review this book first instead of the others I have planned is that I was recently interviewed by a journalist who is writing a brand spankin' new cultural history of lipstick, so hopefully in the next year or so we will have an updated version (and hopefully I will be quoted!) Stay tuned. 😉

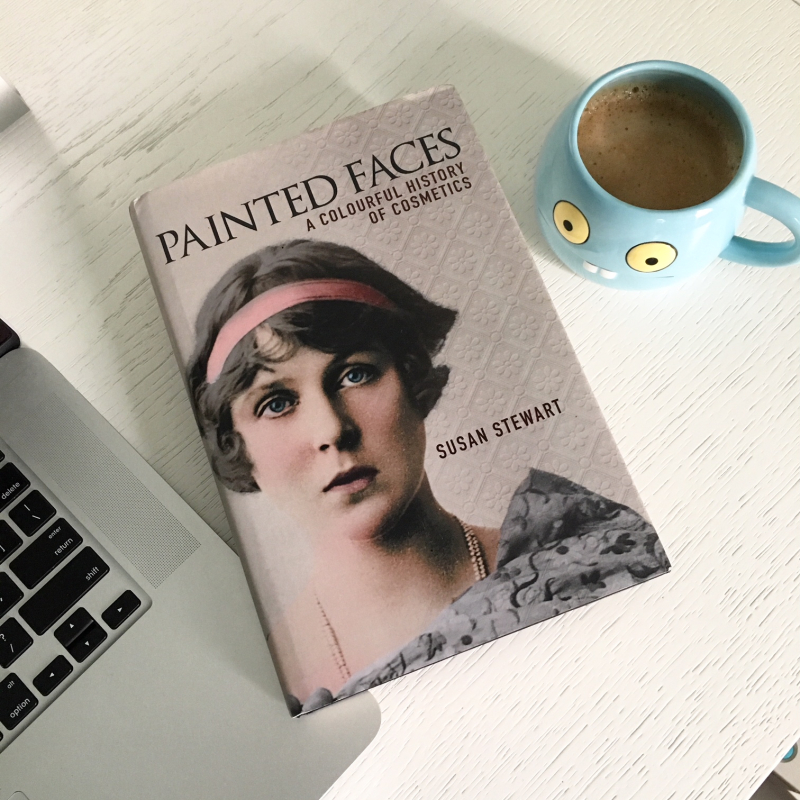

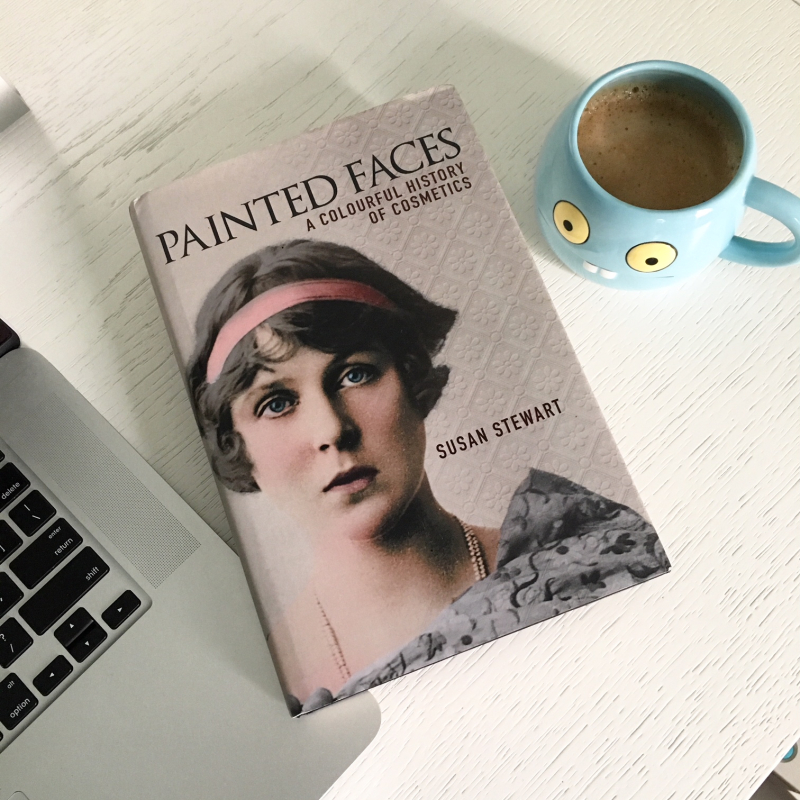

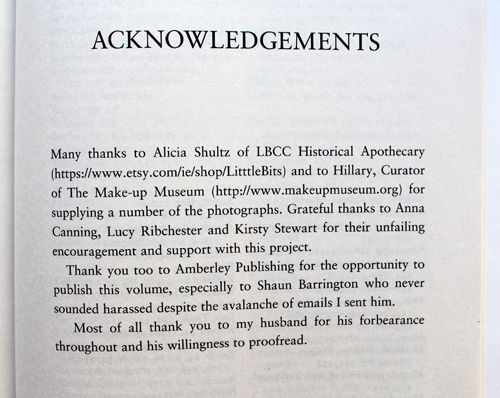

Before I get to my review of Susan Stewart's Painted Faces, I must disclose that I received a copy for free from the author. In no way, shape or form did getting it for free influence my review, nor was it intended as a bribe for a positive one – I believe I was given a copy in exchange for me lending photos of some of the Museum's collection to be included in the book. Not only did Dr. Stewart provide an autograph, she also included me in the acknowledgements, which was incredibly kind.

Again though, I'd like to reiterate that this did not sway my opinion of the book at all. Now that that's out of the way, I can dive into the review.

The goal of Painted Faces is much the same as Lisa Eldridge's Face Paint in that it strives to provide a history of makeup from ancient times to the present day. However, a trained scholar/historian approaches this vast topic in a markedly different way than a makeup artist such as Eldridge. Neither perspective is better or worse than the other; ways to tell the story of makeup are nearly as varied as the people who wear it. Nor do I believe one has to have a set of particular credentials to write accurately and compellingly about makeup history, as I believe it comes down to a matter of preference for a certain writing style. As we saw with her first book, Painted Faces is more academic than Face Paint and relies on highlighting the economic and sociological aspects behind various beauty practices, whereas Eldridge adopts a more artistic tone, choosing instead to communicate makeup's history by focusing on application and styles as they evolved.

Stewart begins with an introduction (which also serves as the first chapter) summarizing the need to study makeup and beauty practices as it gives valuable insight into history that we may not have considered before. "Because of its wider significance, researching makeup, its uses, ingredients, its context and application, can provide clues not only to the nature and circumstance of the individual but can also help us to interpret the social, economic and political condition of society as a whole in any given period. That is to say, studying cosmetics can further our understanding of history…they are a window into the past and can encapsulate the hopes and ideas of the future. In short, makeup matters" (p. 8 and 10). Can I get an amen?! Stewart also carefully sets the parameters for the book, outlining the sources used and why she is primarily writing about cosmetics in the Western world.

Chapter 2 is essentially a condensed version of Stewart's previous tome on cosmetics in the ancient world, which doesn't need to be rehashed here (you can check out my review of that one to peruse the content). That's no small feat, considering how thorough it was. The next chapter covers the Middle Ages, which is interesting in and of itself since so little information about makeup and beauty exist from this era. As Stewart points out, the rise of Christianity meant people were no longer being interred with their possessions as they were in ancient Greece and Rome – these artifacts provided a wealth of knowledge about beauty practices then. Thus, any time after the spread of Christianity and before the modern age historians must rely primarily on texts, such as surviving beauty recipes and classic literature, rather than objects to infer any information about the use of makeup and other beauty items. The dominance of this religion also meant even more impossible beauty standards for women and more shame for daring to participate in beauty rituals. "According to medieval religious ideology, wearing makeup was not only the deceitful and immoral – it was a crime against God" (p. 60). The other interesting, albeit twisted way Christianity affected beauty is the relentless belief that unblemished skin = moral person. Something as innocuous as freckles were the mark of the devil, and most women went to great lengths to get rid of them or cover them so as not be accused of being a witch. I shudder thinking about those who were affected by acne.

Chapter 4, which discusses beauty in the late 15th and early 16th centuries (i.e., approximately the Renaissance) presents the continuation of certain beauty standards – pale, unblemished skin on both the face and hands, a high forehead, barely there blush and a hint of natural color on the lips- as well as judgement of those who wore cosmetics. As we saw previously, it's the old "look perfect but don't use makeup to achieve said perfection" deal – women who wore makeup were viewed as dishonest, vain sinners. But one's looks mattered greatly in the acquisition of a husband, so many women didn't have a choice. "Clearly a woman had to get her makeup just right not simply for maximum effect but to avoid getting it wrong and spoiling the illusion of youth and beauty entirely, a fault that could cost her dearly in terms of wealth, status and security" (p. 94).

However, there were some notable differences between the Renaissance and medieval periods. For starters, due to inventions such as the printing press, beauty recipes were able to be much more widely disseminated than they were previously. Increased trade meant more people could get their hands on ingredients for these recipes. Both of these developments led to women below the higher rungs of society (i.e. the middle class) to start wearing cosmetics. So widespread was cosmetics usage at this point, Stewart notes, that the question became what kind of makeup to wear instead of whether to wear it at all.

This chapter was probably the most similar to those on Renaissance beauty in Sarah Jane Downing's book, Beauty and Cosmetics: 1550-1950. Given the lack of information regarding cosmetics during this time period, both authors had to draw on the same sources to describe beauty habits. However, as with Eldridge, the approaches Downing and Stewart take are slightly different. Once again, Stewart opts for a straighter historical approach whereas Downing looks more to paintings and literature of the time, and doesn't take quite as deep a dive into the larger social and economic forces at work. There's also not much overlap between the descriptions of recipes and techniques, as you'll find different ones in each book. For example, one that was mentioned only in passing in Downing's book was using egg white to set makeup. I'm thinking of it as a early version of an illuminating setting spray (although obviously it was brushed on, not sprayed in a bottle) as it lent a slightly luminous, glazed sheen. Stewart points out that it also caused one's face to crack, thereby eliminating the wearer's ability to make any sort of facial expression. It seems certain beauty treatments, whether egg white or Botox, occasionally come with the side effect of suppressing women's expression of emotion. Coincidence? I think not.

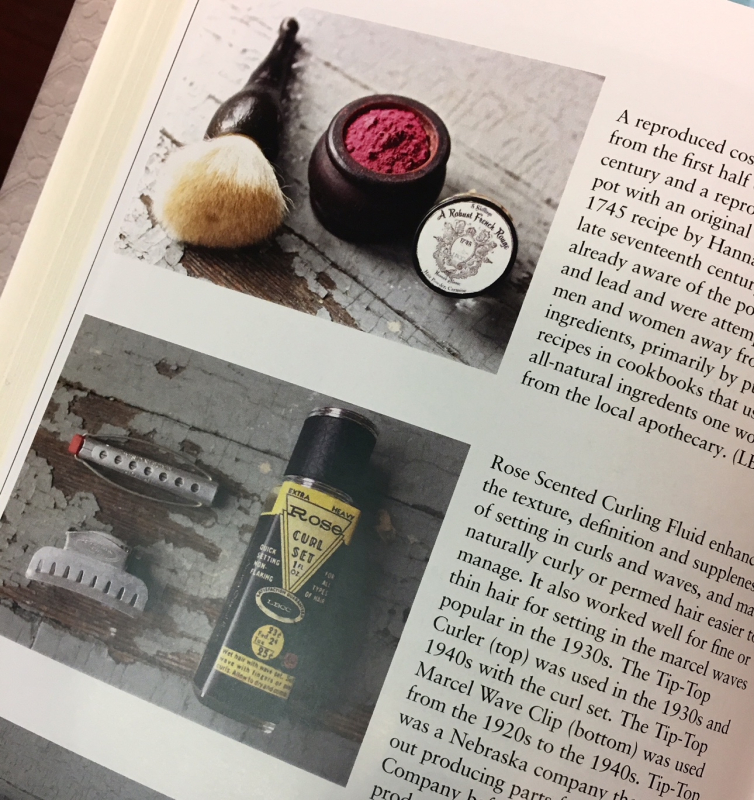

Chapters 5 and 6 are tidily sequential, discussing beauty during the the 17th and 18th centuries, respectively. As in the Renaissance, both eras witnessed significant growth in the number of women who wore makeup due to technological advances and increased trade. Growing literacy rates drove demand for the new medium of ladies' magazines. Pharmacies selling raw materials to make beauty treatments had started to crop up in the 17th century and their numbers increased dramatically by the beginning of the 18th century. Not only that, pharmacies and chemists started offering their own pre-made formulas, and these goods became commercially exported to other countries. The widespread sale of these products came with several undesirable effects: counterfeit cosmetics and downright false claims about the product's efficacy.

The 1700s also saw the rise of excessive, decidedly unnatural makeup being worn by members of the aristocracy in both France and England, followed by a post-French Revolution return to more subtle makeup in the early 1800s. This brings us to Chapter 7, which outlines the myriad changes leading to what would become the modern beauty industry, including department stores, industrialization and the new commercial market of the U.S. As for beauty standards, a natural look was still strongly preferred by both men and women, with the emphasis in terms of products on skincare rather than color cosmetics. Here's a literal lightbulb moment: despite my research on Shiseido's color-correcting powders, in which I learned some were meant to counterbalance the effects of harsh lighting, I had completely overlooked the influence of artificial light on the skyrocketing production of face powders. "Suffice it to say that in the early years of the twentieth century, the use of artificial light in homes of the wealthy as well as in public places such as theatres and concert halls would become more widespread, in the latter years of the nineteenth century there was already an understanding that to make the best impression, makeup needed adjusting to suit the light, whether it be natural or artificial" (p.198).

Chapter 8 leads us into the 20th century. While there are more detailed accounts of makeup during this time, Stewart does an excellent job describing the major cultural and technological influences that shaped modern beauty trends and the industry as a whole. I was very impressed with how she was able to narrow down the key points about 20th century beauty without regurgitating or simply summarizing other people's work. Some of the information presented is familiar, of course, but the manner in which it's arranged and categorized sets it apart. It just goes to show that everyone's individual background equals an infinite number of ways to tell the story of makeup.

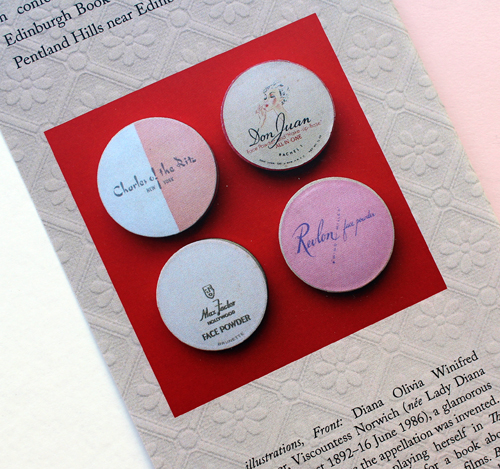

I'm partial to this chapter since the items I took photos of for the book are all from the 20th century. :)

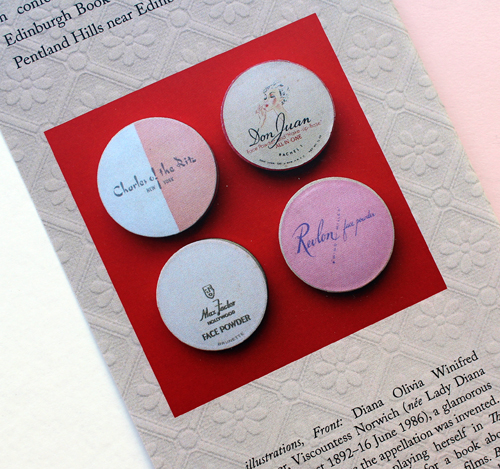

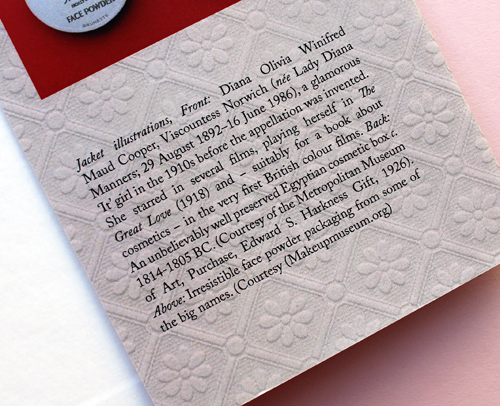

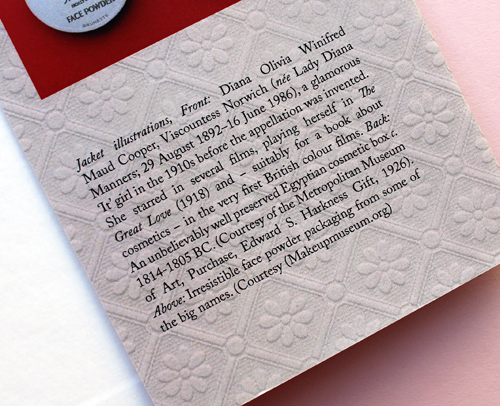

Here are some powder boxes on the dust jacket.

While I was deliriously happy to see some of the Museum's items in a real published book and get credited for them, I was also pleased to see photos of other pieces as well. Their inclusion in addition to illustrations was a bit of an upgrade to Stewart's previous book. This is a minor issue to be sure, as I believe solid writing more than makes up for a lack of photos, but they are a nice touch if available.

The last chapter serves as an addendum in which Stewart reflects on how the past, present and future of beauty are linked, noting that while some things have stayed the same – the use of ancient ingredients in modern formulas, the connection between health and beauty – 21st century attitudes towards cosmetics represent a significant change from earlier times.

Overall, this is a more scholarly history of makeup than we've seen before, but by no means dry and boring. Stewart's gift for wading through hundreds of historical documents and neatly consolidating the major social, economic and cultural forces that shaped makeup's history, all while sharing fascinating snippets such as ancient beauty recipes and anecdotes from people who lived during the various eras she covered, makes for a thoroughly engaging read.

Will you be picking this one up?

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save