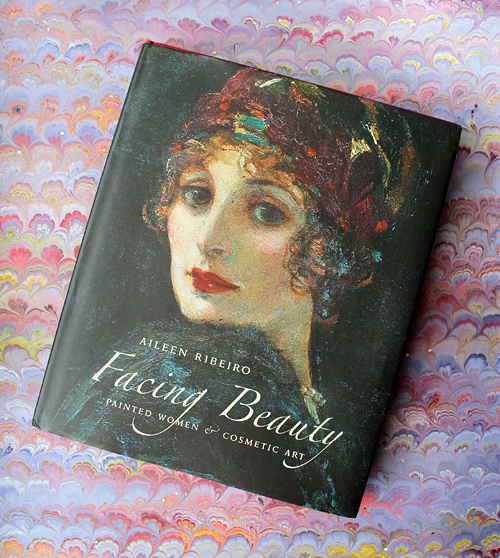

I'm embarrassed to say that Facing Beauty: Painted Women and Cosmetic Art has been in my possession for well over a year (along with many others). As usual, it's not due to lack of interest that I hadn't gotten around to reading and reviewing it but rather the relentless lack of time. I was more than excited to dive into Facing Beauty, as it's written by Aileen Ribeiro, a renowned fashion/art historian (ahem!) and I always welcome an examination of makeup through an art history lens.

Ribeiro's premise is the exploration of Western beauty ideals from the Renaissance through the early 20th century (roughly 1500-1940) as portrayed in painting and literature, and how cosmetics both helped create and achieve these ideals. Facing Beauty is not intended as a fairly straightforward history of makeup nor is it strictly art history with a dash of cosmetics; rather, the book seeks to trace the evolution of what the Western world considered beautiful in particular points in time using art from those eras, and along the way, identifies makeup's role the formation and realization of beauty standards.

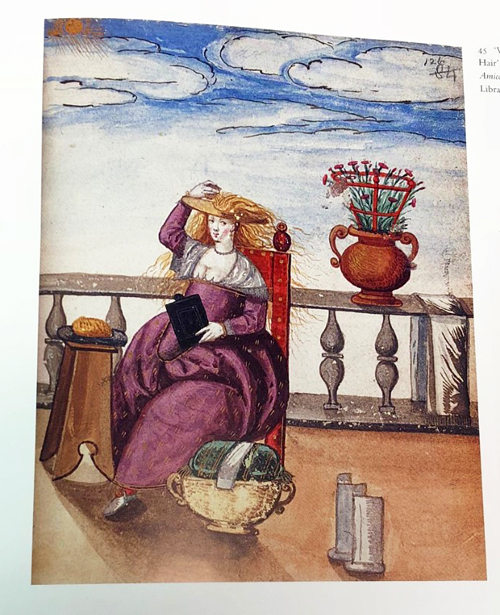

Chapter 1 covers the Renaissance period and appropriately begins in Italy, as the country served as the primary locus for Europe's cultural rebirth. Ribeiro reminds us that it was a time of lively cultural debate, and the topic of what constituted beauty was fervently discussed. Renaissance thinkers pondered beauty in all its forms, including the ideal female face and body. By and large, the ideal Renaissance woman possessed pale, flawless skin, sparkling yet dark eyes (sometimes achieved with the essence of the deadly nightshade plant, a.k.a. belladonna), a long straight nose, and a small mouth. Tidbit: did you know that blonde hair was preferred throughout the Renaissance? I didn't, nor did I know of the ridiculous lengths women would go to in order to acquire it, such as using this crownless hat (known as a solana) combined with a thorough application of various dyeing potions (some made with dangerous ingredients such as alum, some with harmless ones such as lemon juice) via a small sponge (sponzetta), along with a hefty dose of sunshine.

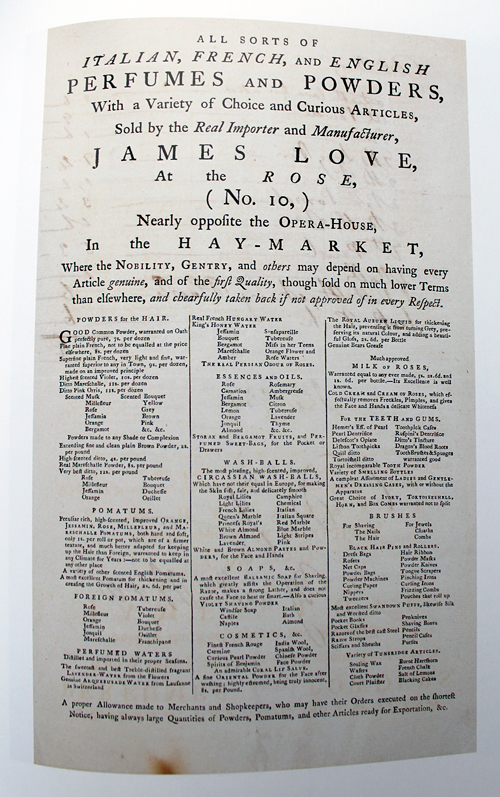

In painting and literature, women were still viewed as mostly decorative objects, existing only to be admired. Women's attempts to adhere to the established beauty standards, including the use of makeup, were actually expected and encouraged: it was their duty to appear pleasant to look at. "It was important for a woman to be physically beautiful (or try to be so), as a courtesy to others, and thus cosmetics were allowable as long as they were used in moderation. These themes appear over and over again throughout the [16th] century, as the idea of dress and appearance being pleasing to others began (unevenly at times) to replace the traditional Biblical belief that such things were indicative of pride and vanity." (p. 71) But as the Renaissance spread to Northern Europe, in the early 1600s cosmetics were becoming increasingly criticized for allegedly inciting vanity among women. Indeed, the debate over whether women should or shouldn't wear "auxiliary beauty" reached a fever pitch by the middle of the 17th century. By the late 1600s, with flourishing trade leading to an increase in the number of beauty products available to the average woman, the pendulum had swung back towards a mostly positive view of makeup. This in turn set the stage for the fashion excess so emblematic of the 1700s, as well as the establishment of a woman's "toilette" (formal beauty routine).

This brings us to Chapter 2, an overview of beauty ideals during the Enlightenment, which spanned approximately from 1700 through the early 1800s. Ribeiro explores how the era's leading philosophers continued the Renaissance's debate on beauty. Theoretically it represented a departure from Renaissance thinking in that writers and artists of the time no longer believed that a woman's face and body had to be perfectly proportional or symmetrical in order to be beautiful. Beauty was now in the eye of (male) beholder and also took a woman's personality into consideration. However, Enlightenment thinkers still clung to the usual standards of fair, clear skin, a high forehead, straight nose, and rosy lips and cheeks. One of the highlights of this chapter was the author's discussion of excess in fashion and beauty, including the fabulously elaborate toilette. I mean, look at this set from around 1755. How opulent! Wouldn't you love to get ready with this on your vanity? It's currently housed in the Dallas Museum of Art, but obviously I think its rightful home is the Makeup Museum. 🙂

(image from the Dallas Museum of Art)

Another fun little nugget of information: I knew a bit about how beauty patches were all the rage during this era and that their placement symbolized certain things from Sarah Jane Downing's Beauty and Cosmetics: 1550-1950, but I did not know that each area of the face corresponded to a zodiac sign – put a patch on your chin to show you were a Capricorn, or one over the left eye to signify your Aquarius sign. I'm astonished that the notion of matching beauty products to your zodiac sign goes all the way back to the 1700s! Of course, the heavy makeup worn by royalty and other upper-class women was not without its critics, especially artists. Ribeiro thoughtfully points out another connection between makeup and art: The excess caused painters to question whether they could capture a woman's true likeness and what exactly they were painting – the sitter or her makeup. "How much face painting was there meant to be in the painting of a face?" (p. 184) It also moved the age-old question of how one could determine a woman's "real" beauty if she was wearing layers of makeup to the forefront once again. But as we know, the passion for over-the-top fashion and makeup quickly died out as heads rolled in the late 1700s. Thus Chapter 2 concludes with a discussion of the return to a more natural look, in keeping with the Neoclassical style that permeated every aspect of post-revolution French culture. Makeup was still used to achieve what was thought of as ancient Greek or Roman beauty (think LM Ladurée and Madame Recamier), but the days of wearing thick layers of white paint (the ever-deadly ceruse), heavily rouged cheeks and patches were over. Nevertheless the market for makeup and skincare products continued to grow despite the even more austere approach to makeup following the decline of the Neoclassical style during the 1820s.

The last chapter was my favorite, as it outlines the development of modern beauty ideals from the 1830s through the early 20th century as well as how the beauty industry both shaped and was shaped by these notions – a topic I'm endlessly fascinated by due to its complexity and the fact that it serves as the foundation (haha!) of the makeup styles and looks we've come to rely on in the new millennium. Ribeiro's take on the rapid developments during this time, which represented a sea change in beauty culture, is quite different from other modern beauty histories such as Kathy Peiss's Hope in a Jar and Madeleine Marsh's Compacts and Cosmetics. As I noted earlier, Facing Beauty isn't meant to be a fairly straightforward history of cosmetics, and the last chapter describes some parallels between art and makeup that, in my opinion, are even more insightful than those in the previous chapters.

Earlier in the 1800s, beauty was more prominently linked to health and hygiene than in previous eras, hence the rise of historic soap companies like Pears, and remained that way till the early 1900s. The middle of the century also witnessed the birth of the societal norm of less makeup on "proper" (i.e. upper and middle-class) women; a noticeably painted face became associated with prostitutes, or at least the lower classes. This is more or less a twist on the long-standing association between beauty and virtue. Ribeiro notes that improvements in sanitation and medicine had largely eradicated the need for heavy makeup anyway. Shops were now promoting mostly skincare, light face powder and blush, eyeliner and brow powder. The author also points out how beauty became synonymous with cosmetics, perhaps rendering traditional ideas of beauty obsolete. In 1904 Australian artist Rupert Bunny depicted a modern-day version of the Three Graces applying powder and lip color, which, according to the author, is most likely the first time in the Western world that ideal beauty is directly associated with makeup.

In the 1910s makeup became more visible, both on the women wearing it and its widespread commercial availability. Ribeiro identifies another interesting connection between art and makeup during this time: bolder, more colorful abstract art inspired vibrant makeup. As an example the author uses the painting Maquillage by Natalia Goncharova, which "shows the bright primary colors and abrupt angular lines that [Goncharova] saw in contemporary makeup, a startling contrast to the soft and tender, 'ultra-feminine' beauty of the turn of the century. Cosmetics as art were influenced by art – the vivid colors seen in the work of the Fauves and in the clashing and barbaric beauty of the designs for the Ballet Ruses." (p. 298).

(image from the Dallas Museum of Art)

At this point makeup was also seen as essential for a woman's professional success in addition to landing a husband. Nevertheless, the free-spirited flapper era might be the first instance of women wearing makeup solely for themselves, as a symbol of their independence. The 1930s, a decade in which movie stars captured the hearts of audiences across the globe, is when cosmetics became inextricably linked to glamour and the ultimate symbol of femininity. And by the end of the second World War, makeup "was no longer associated with deceit, with disguising the real woman, and it had largely (if not completely) become free from association with immorality and sexual temptation. Most of all, beauty was regarded as something achieved by cosmetics, by science, rather than inherited; it was a commodity, no longer elitist but democratised," Ribeiro concludes (p. 325). The epilogue summarizes the attempts made from the mid-20th century until roughly now to define beauty and where cosmetics fit into a discussion about modern-day beauty ideals. It was well-written, but obviously I think another entire book on that time frame would make an amazing sequel.

Overall, I'd say Facing Beauty is a more in-depth version of the aforementioned book by Sarah Jane Downing, as they cover the same time periods and draw on many of the same sources. While it was an excellent read, I remember my dismay regarding the brevity of Downing's book. Facing Beauty expands on Downing's work by offering a lengthier analysis of art and literature to help tell the story of makeup and beauty, as well more information on beauty recipes and ingredients. The latter reminds me a bit of Susan Stewart's wonderful Painted Faces. However, Facing Beauty does not delve much into the societal role of cosmetics, an aspect that makes Stewart's book stand out from other cosmetics history tomes. In any case, it's a thoroughly enjoyable and well-researched read, and a must-have for anyone who wants to learn more about the intersection of art and makeup. As compared to other books in the same vein, Facing Beauty provides the quintessential overview of Western beauty ideals as seen through an art historian's perspective and thoroughly covers how makeup corresponds to them.

Have you read this one? If not, are you interested in checking it out?