My heart skipped a beat when I spotted what Sulwhasoo had up their sleeve for this year's ShineClassic compacts. Every year the company collaborates with an artist who represents an aspect of Korean artisan culture to create a design for two compacts, a tradition Sulwhasoo began in 2003. Master craftswoman Hong Jeong Sil was selected to produce the ShineClassic compacts for the 2018 holiday season. We'll delve more into the traditional metal inlay technique known as ipsa that Hong used to create these stunning pieces, but first, let's take a look at them in all their glory. Unlike last year's release (another that I never got around to writing about, sigh), this year I was so smitten with the design I got both compacts, steep price tag be damned. I really try to only buy one since the designs are the same, just with different color schemes, but I simply couldn't resist these!

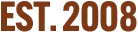

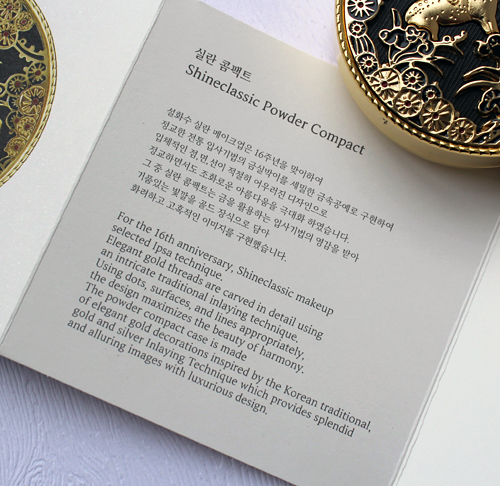

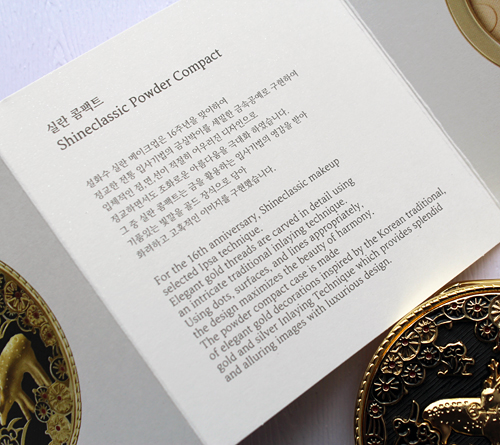

Even the boxes are works of art inside and out.

So luxurious!

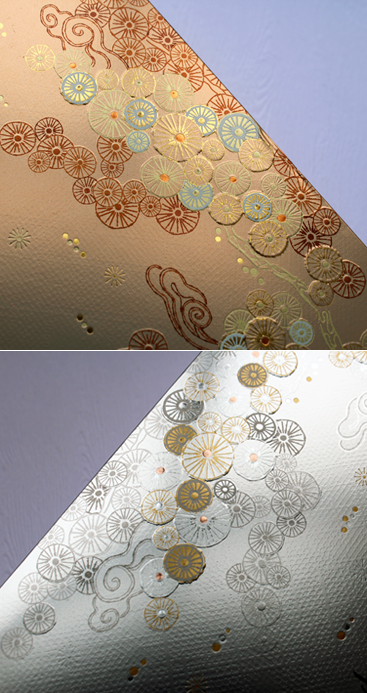

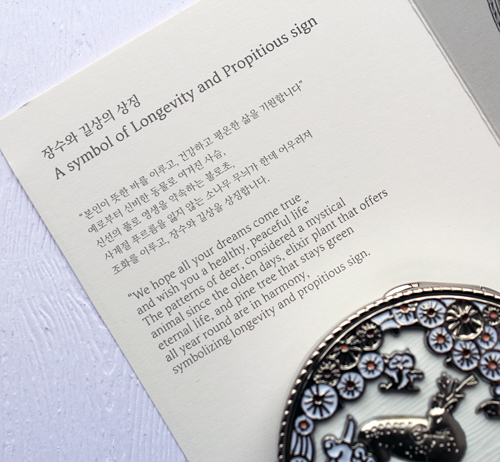

The inside of the lids are etched in a metallic finish depicting a charming nature scene with trees, waterfalls, birds, deer and even a turtle. According to the Sulwhasoo website, these "symbolize longevity and great fortune, carry the message 'One can achieve his or her purposes and lead a healthy, peaceful life.'" As it turns out, the inclusion of these motifs is not accidental. Like many Korean artists, Hong is inspired by a traditional group of ten symbols of longevity collectively known as Ship-jangsaeng: Sun, mountains, water, cranes, turtles, pine trees, bamboo, mushrooms, deer and clouds. I thought the whole scene was merely cute and whimsical and that Hong just personally found these images enjoyable – I had no idea how culturally significant these motifs are.

The intricacy of the compacts themselves is exquisite.

Of course, I managed to nick the powder on this one…I must learn to control my excitement when handling Museum objects.

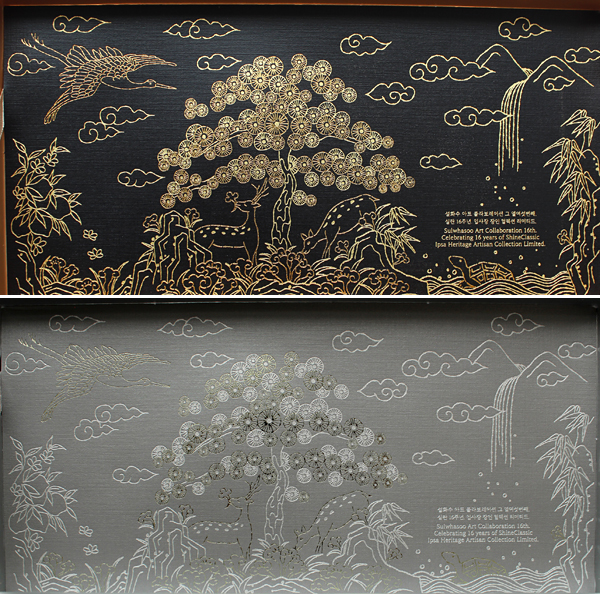

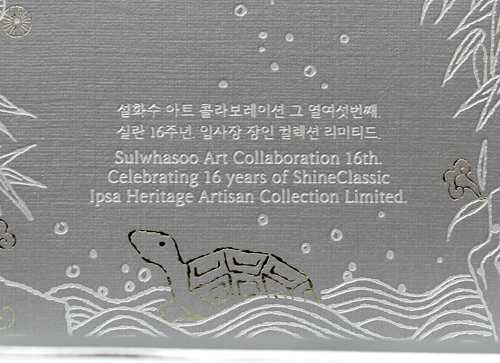

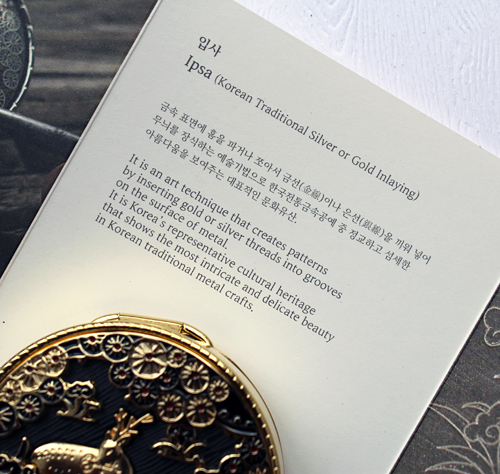

Here's some of the pamphlet that tells a little bit about the ipsa tradition.

So what exactly is ipsa? I'm afraid I can't go into too much detail since I completely didn't see this entire book on it until it was too late, but hopefully what I was able to gather online will suffice for now. (I plan on ordering the book and updating this post accordingly, if I remember.) Basically ipsa is the art of inlaying thin, delicate strands of silver, copper or gold onto a metal surface. It's similar to damascene and other metal inlay techniques found around the globe, but two elements make ipsa uniquely Korean: the focus on graceful lines and the preference for silver over other metals. This very helpful article from Koreana magazine explains the history and general style of ipsa. "During the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) and the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), it was developed into a brilliant art form, representing the epitome of metal craft. Still, Korean metal inlay is unique for its emphasis on the 'art of lines.' The designs made with lines of a consistent width are simple yet artistic, basic yet whimsical. Designs expressing wishes for good fortune and prosperity, health and longevity, abundance and fertility, or images of the ten symbols of longevity (including birds and flowers, grass and insects, and landscape scenes with ducks in a stream under weeping willows), were crafted onto incense burners, braziers, tobacco cases, clasps, and stationery items, which were always kept close at hand and appreciated for their refined appearance…Though gold was rarer, silver was the preferred choice…Silver is rather plain by itself but radiates brilliance when combined with other materials. It has a subtle elegance that endures over time, rather than something fancy that can quickly fade. These qualities of silver appeal to the inherent nature of the Korean people, which is why silver was most commonly used for metal inlay work." Hong's work for the Sulwhasoo compacts definitely represents the traditional ipsa style through the "basic yet whimsical" lines and symbols of longevity.

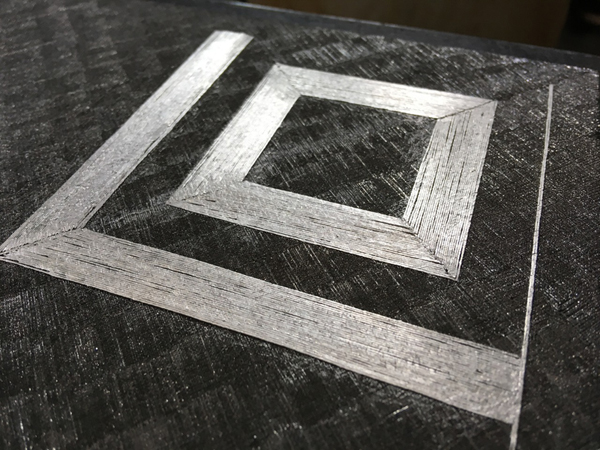

Like the other holiday collabs we've seen so far, ipsa requires precision and painstaking labor. The patterns must be carefully drawn out on the surface before the inlay is applied. Each strand of metal, some as thin as .25 millimeters, must be formed by hand and then attached to the surface individually. This means even a very simple line takes hours. Over 30 types of tools are used – everything from pliers and hammers to tweezers and chisels. As Hong says, it's essentially "embroidery with metal." Sulwhasoo provided a few snapshots of the process, but I would have loved to see a video showing Hong creating the original design.

Additionally, there are two main types of ipsa. I'll let Koreana take over again: "The first, called kkium-ipsa, involves incising a decorative design onto the surface of a metal object using a burin, and inlaying the threads of silver into the incisions. This technique was widely used during the Goryeo Dynasty. Because Goryeo had adopted Buddhism as its official religion and ideology, the metalworks that were produced primarily included bronze Buddhist implements, such as incense burners, incense cases, and kundikas. During the subsequent Joseon Dynasty, Buddhism was suppressed and supplanted by Confucianism. The production of bronze Buddhist implements thus diminished, while large quantities of ironware items were supplied to the royal palace and the homes of the elite class. Since the major material for metalworks was now iron instead of bronze, it was necessary for the metal inlay techniques to be adjusted accordingly. This led to a second technique, jjoum-ipsa, in which the entire surface of a metal item is uniformly incised and then silver thread hammered into the incisions. This is the technique that Hong learned and applies in her works today. The surface has to be engraved four times, each time in a different direction, which calls for painstaking patience and perseverance." There was only one design for Sulwhasoo intended for a small surface so it may not have taken that long, but the shapes clearly require a lifetime of skill. I might be able to inlay a single pre-made strand of silver onto a surface in a straight line, but could I form many strands into deer and trees? No way!

(images from sulwhasoo.com)

(images from sulwhasoo.com)

In addition to the Sulwhasoo compacts, another impressive example of the labor involved to produce an ipsa piece is this vase by Hong. I can't even imagine how long it took, since it appears to use three different kinds of metal of varying lengths to form a pattern. There must be hundreds of individual strands.

I also wanted to share this image from Hong's protege, who is taking ipsa in a very futuristic direction by creating a QR code that can be scanned and connected online. The code is made with very thin strands of silver inlaid on an iron plate. Again, each strand is handmade and applied individually. It must take hours to get them to perfectly line up; otherwise, I suspect the code might not work.

(image from ipsajangproject.tumblr.com)

The final element of the ipsa technique is making a black background (historically from burnt pine soot) or leaving it unfinished. "Those parts of the surface not inlaid with silver thread are colored black, using traditional techniques, or left unfinished to emphasize the natural color and texture of the metal. The black background surface contrasts with the sheen of the silver thread and highlights its brilliance. In the past, the soot of burnt pine was mixed with vegetable oil to make the black coloring, but these days powdered graphite is used. After applying the black coloring, the surface is rubbed with vegetable oil and then polished to a lustrous finish." I'm not sure how the background for the original design of the gold ShineClassic compact was created, but it's truly striking. I am a bit puzzled as to why the silver toned compact is on a white background, however.

As did Yang Huazhen and Zhang Xiaodong, a Qiang embroiderer and kite maker, respectively, who collaborated with Shu Uemura, Hong answered the call of reviving a dying cultural tradition and more or less single-handedly brought it back from the verge of extinction. Born in 1947, she graduated in 1969 from Seoul Women's University with a degree in crafts, followed by a graduate degree at Seoul National University in 1971. While studying there, she came across an old ipsa piece in an antiques district and it was "love at first sight": "'The silver thread embroidery of the old metal artifact seemed to reveal the purity of the artist's heart and spirit. I was spellbound by the beauty and started to ask around about learning metal inlay. But I was surprised to find that it was a disappearing art. In a book, Human Cultural Treasures, that I had come across by chance, it said that 'traditional metal inlay is no longer practiced,' which bothered me so much I couldn't sleep that night.'" Hong was struck by the fact that there were so few artisans left, and took it upon herself to learn ipsa in order to preserve Korea's cultural history. "It was almost like the book was assigning me a mission," she says. After five years of searching, she found one of the few remaining ipsa artists, Lee Hak-eung, who took her on as an apprentice. Even though Lee was nearing 80 years old and hadn't actively practiced ipsa in over 10 years, he agreed to be Hong's instructor. At first he was reluctant to teach her ("Why do you want to learn this? It is a difficult road paved with poverty," he told her) but knowing that ipsa was nearly wiped out, coupled with Hong's dedication and talent, eventually he relented. There was a steep learning curve, as Hong soon found out. "The hardest part about learning everything was the lack of ‘curriculum,’ so to speak, because there was so little information available about ipsa at the time. Nobody had really researched it because hardly anyone even knew about it. It had basically been abandoned," she says.

(image from magazine.seoulselection.com)

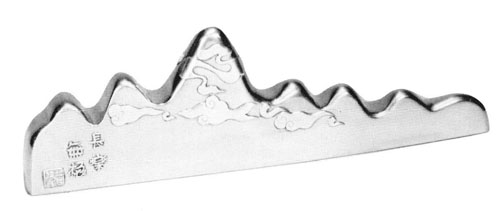

Under Lee's tutelage, Hong quickly realized that ipsa needed to be officially recognized by the Korean government in order to not disappear completely. For her, getting ipsa on the government's radar, along with educating a new generation about it, were just as important as learning its technique in terms of preservation. “If people don’t know about it, then it won’t stay alive. You can’t keep something alive simply by being very good at it, because then it ends with you. You have to let people know; you have to show them." Hong submitted a comprehensive report documenting every ipsa piece she could find, and because of this effort, the craft was registered as an "important intangible cultural property" in 1983. Hong went on to establish her own school, the Gilgeum Handicraft Research Institute, and in 1996 she was awarded the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea No. 78, making her the official holder of ipsa (Lee was the previous holder and had passed away in 1988). Making ipsa modern was also an important lesson. "I learned that metal inlay could not be done if the hands did not follow the heart. I also realized that although I was learning a traditional art I would have to develop it to fit modern times," Hong says. While the Sulwhasoo compacts depict fairly traditional Korea motifs, Hong's other work expresses a more modern sensibility. Take, for example, this sculptural paperweight/brush rest from 1980 that resembles a post-modern mountain range.

(image from ganoskin.com)

And the painterly flourishes on this vase from 2013 merge a classic silhouette with 21st century abstraction. As Hong notes, "Tradition and modernity, past and present, aren’t separated by some boundary like some people think. They are inevitably linked. The past isn’t over; it illuminates the present and helps reveal the future."

(image from constancychange.kr)

While Hong has made a career out of rescuing ipsa, she doesn't think Korea's modernization necessarily caused it to be almost completely erased from history. In fact, she believes the modern era helped Korea reflect on its cultural heritage. Explains Hong, “Some people despair at the disposal of traditional culture that occurred throughout Korea’s often rushed modernization, but I think it couldn’t have been any other way. Only now can we afford to look back and reflect on what can be learned from our past, on what can be salvaged. Only now do we have the economic status that affords us the ability to value our traditional culture…Korea’s culture and traditional arts are getting more attention these days, not because they’ve gotten better or more beautiful – they’ve always been beautiful – but because people’s perceptions have changed. Korea’s original sense of beauty, something only we can intuitively know, is finally getting some attention." I'd add that it's far easier to connect with aspiring artisans and reach the public at large nowadays. While educating new generations via the usual methods (schools, museums, etc.) is critical, a beauty collaboration is a wonderful way of bringing people's attention to an otherwise little-known art form and in this way, helps preserve it.

In conclusion, I thought Hong's work translated beautifully to the compacts. While perhaps not as intricate as the original ipsa design they're based on, the engraving captures the essence of the technique and ipsa's overall style. Ipsa is heavily focused on lines, and the beauty and grace of Hong's shapes remained intact on the compacts (i.e. they didn't get out of proportion or distorted). Elaborate metal compacts such as Sulwshasoo's ShineClassics are obviously the perfect vehicle to showcase a historical metal inlay technique. And as with all artist collabs, I'm happy to have learned about such a historic part of Korea's culture, and I appreciate people like Hong keeping it alive. Hong is equally pleased to share her work: "I want to make Korean-style beauty known to the world. I want people to exclaim: 'So this is what Korea is about. This is the beauty of Korean silver inlay.'" Mission accomplished!

What do you think of these? Have you ever heard of ipsa?