Makeup Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning. I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

A while back the excellent fashion blog Worn Through had a post questioning whether fashion curators needed to also be designers, or at the very least, know how to sew. It got me thinking whether the same conundrum would face a beauty curator, i.e., does one need to be a professional makeup artist to oversee a beauty museum?

A while back the excellent fashion blog Worn Through had a post questioning whether fashion curators needed to also be designers, or at the very least, know how to sew. It got me thinking whether the same conundrum would face a beauty curator, i.e., does one need to be a professional makeup artist to oversee a beauty museum?

My gut reaction, naturally, is no. The curators at most art museums are not artists themselves. And as Jill points out in her Worn Through post, a background in art history and museum studies and/or cultural studies is more crucial for fashion historians and curators than being able to construct a garment. Seeing as how I have degrees in art history and cultural studies, plus work experience at several museums, I think I'm very qualified to be a beauty curator. Moreover, I'd argue that just because one is a professional makeup artist doesn't necessarily mean they're any more knowledgeable than I am about beauty history.

However, besides the fact that in recent years there's been a growing interest in the idea of the artist as curator, it is undeniable that a professional makeup artist would possess an abundance of knowledge that would prove useful in a museum or academic environment. An artist working at a department store counter, for example, understands the cosmetic needs of the average woman, which would be a valuable topic to contribute towards a book or exhibition on contemporary culture. Meanwhile, celebrity makeup artists and beauty directors for fashion houses offer a unique perspective on the relationship between fashion and makeup. They themselves are setting the trends – in effect, helping to create beauty history. Then there are the artists who do it all, from showing non-makeup pros how to easily achieve a certain look to providing their services for magazine photo shoots and runway shows. Case in point: Lisa Eldridge, a makeup artist whose enormously popular YouTube videos shot her to fame, is releasing a beauty history book this fall entitled Face Paint: the Story of Makeup. As Alex at I Heart Beauty says, "if anyone's qualified to tell the story of makeup it's Lisa Eldridge."

So where does that leave us? While I believe professional makeup artists could also make good beauty historians or curators, I still don't think being a pro is an absolute necessity. If you look the beauty history books that I've reviewed or recommended, many of them are not authored by pro makeup artists. It's a mixed bunch of historians, independent authors and collectors. I was also thinking of other fashion curatorial and history luminaries – do you think Valerie Steele or Tim Gunn could make a garment? Highly doubtful. While my application skills are nowhere near the level of a professional's (I still can't do winged eyeliner to save my life), I at least know which colors and looks are flattering on me, and I continue to experiment with the latest products and techniques. And given my art history background, I can also both appreciate and analyze the work of pros that I see in magazines and runway shows and on blogs. Combined with my passion for art, design, history and fashion in general, I think this is more than enough to run a beauty museum.

Having said all that, I do think it's necessary to have some knowledge of basic application and an interest in fashion. Makeup doesn't exist in a vacuum, and I think it may be difficult to curate a beauty museum without having at least some sense of which product goes where on one's face, how makeup artists use these products to create various looks, and a cursory knowledge of high-end fashion brands. How else would you come up with exhibition themes or know what's worth purchasing for the museum's collection? Additionally, it wouldn't hurt to familiarize yourself with vintage cosmetics objects in order to gain a better understanding of product design and how it's evolved over the years, not to mention the cultural history these objects reflect.

What do you think? Do you think would-be makeup museum curators need to go to beauty school or are the other skills and knowledge I've mentioned sufficient?

Makeup Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning. I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

The idea of fundraising makes me very uncomfortable, so much so that I've always avoided the topic. However, I came across this article over at Gawker about sad Kickstarter projects that received zero money and decided this would be a good time to address fundraising; specifically, a new way of raising money known as crowdfunding. The article captures why I'm not doing anything of this sort at the moment, so I thought today I'd explore the idea of crowdfunding for museums and why I don't want to engage in it for the Makeup Museum.

The idea of fundraising makes me very uncomfortable, so much so that I've always avoided the topic. However, I came across this article over at Gawker about sad Kickstarter projects that received zero money and decided this would be a good time to address fundraising; specifically, a new way of raising money known as crowdfunding. The article captures why I'm not doing anything of this sort at the moment, so I thought today I'd explore the idea of crowdfunding for museums and why I don't want to engage in it for the Makeup Museum.

Museums can certainly benefit by using crowdfunding, especially since, as this post over the Center for the Future of Museums blog points out, Kickstarter and the like reduce funders' risk (you only pay what you pledged if the full goal is reached) and also have the ability to go viral via social media, something that doesn't happen with the more traditional fundraising methods. The social media aspect also helps target the all-important youth demographic.

Indeed, some campaigns are wildly successful, like the one for the Tesla Museum run by The Oatmeal artist Matt Inman.* Smaller projects exceed funding goals as well, like the Chicago Design Museum, the Hollywood Science Fiction Museum or the Museum of Food and Drink. Like the Makeup Museum, these were the long-term projects of a few dedicated people that were finally able to have a permanent physical space thanks to Kickstarter. On an even smaller scale money-wise, various exhibitions hosted by existing museums, on subjects ranging from burlesque costumes to the work of cartoonist Al Jaffee and costing just a few thousand dollars, regularly meet their fundraising goals. This isn't surprising, as the founders of Kickstarter publicly announced in 2013 that they are looking to help fund museum exhibitions and other projects. The funds cannot be used for operational costs, but go towards "specific programming or ventures".

So it would seem as long as you aim low and keep the total goal below $20,000 (unlike these unsuccessful campaigns – they went big and failed), your museum, or at least an exhibition, would have a good shot at getting funded. However, there's really no predicting what will get the cash rolling in. Even smaller projects that ask for $20,000 and under – and that also seem pretty cool to me – got next to nothing. Why do people not want to fund toy museums? Or an exhibition on queer fashion at the Fashion Institute of Technology? The results are even more dismal at Indiegogo – my museum search there yielded literally hundreds of museums and exhibitions that didn't earn a single cent. (Note: This is partially due to Kickstarter completely dominating its crowdsourcing platform competition.)

Additionally, the overall rates are not great either. In 2012 only 50% of crowdfunding campaigns got funded. On the Kickstarter stats page, as of today the success rate for the categories of design and art were 36% and 45%, respectively, with fashion coming in at the second lowest of all categories (27%). I'm guessing the Makeup Museum would fit somewhere in one of those three, and those are even less than the 2012 global average of 50%. I'm a glass half-empty kind of person so I'm not willing to do the amount of work required to develop and launch a campaign – the odds of my museum getting funded would have to be drastically higher. Moreover, the most successful campaigns are ones that are backed by a massive social media presence, something the Museum sorely lacks. I hate Facebook, I only have a handful of followers on Twitter and Pinterest, and only just yesterday did I reach an average of 100 page views. (Sometimes blogging is a lot like high school, i.e. a popularity contest, something I never win.) And unlike most beauty bloggers, I have zero connections to the beauty industry. If an influential beauty blogger who is regularly in touch with PR reps from a big cosmetics company decided to start a Kickstarter campaign for a makeup museum, they'd have no trouble at all – I could absolutely see L'Oreal or Estée Lauder doling out the cash pretty easily. No one, especially a huge company, is going to want to back something that doesn't have a significant following on social media.

Then there's the matter of asking friends, family and strangers for money via social media, an idea that makes me very uneasy, especially when it comes to the first two categories of people (see the some e-card above). I would never ask them to contribute to the museum face-to-face, so why would a crowdfunding campaign be acceptable? I'd be fine applying for a grant from a foundation because dispensing funds is what a foundation does, but crowdfunding just seems like standing there with my virtual hand out begging for money.

Finally, the emotional risk is too great. I wouldn't lose anything financially, but I would be so crushed at not reaching even a small goal. The only thing I'd even consider using Kickstarter for would be my oft-mentioned coffee table book that I never get around to working on (or my '90s beauty book). That seems like a worthwhile, tangible item that people may be willing to pay for and it's small enough that it could be feasible, but I'd be so sad if people didn't want to pay even for a book. Anyway, the museum is a reflection of me and I absolutely would take it personally that the campaign failed. Unsuccessful blogging is one thing – I enjoy blogging for its own sake so a lack of readers and page views doesn't bother me that much – but a failed crowdfunding campaign would really sting.

Speaking of which, there's the matter of the logistics of developing a good campaign that would make this seem like a legitimate museum and not just a pet project that some crazy lady with a lot of makeup dreamed up. I know if I don't do a perfectly on-point campaign, there's no way people are going to give their hard-earned dollars for something they perceive as another vanity project. With no background in fundraising and no real creative skills, I couldn't fathom designing an appealing campaign that people would see as worthwhile. Also, not only would I be sad and embarrassed, I'd also be enraged people were willing to pay $55,000 for some guy to make potato salad while my idea went nowhere.** A beauty museum may not be brilliant but it's better than potato salad! Overall I'm already disappointed and frustrated about the direction my "career" took, so I simply cannot tolerate another failure involving something else I hold so close to me.

There is another crowdfunding platform that deviates slightly from the Kickstarter/Indiegogo models, but I don't want to use that either. Patreon is a way for people to pay on an per-project basis, i.e. you can "commission" an artist to create something, be it a song, a painting, or a movie. But many bloggers use it as a way offset some of the costs that come with providing quality content, or to get paid for blogging in the hopes of transitioning into their projects full-time. One Tumblr I follow, Medieval POC, uses Patreon to help pay for costs such as academic database membership fees as well as projects like a print shop and "theme weeks", i.e. posts on a specific topic.

Plus, Patreon doesn't seem quite as obligatory as a typical crowdfunding campaign. People can still access any content on your website for free, and you can just sneak up a donation link somewhere on your site – no fancy campaign and networking required (although I guess if you want more people to give you'd have to make some kind of announcement). They only donate if they choose and to whatever project they want. I imagine that if I implemented it for the Makeup Museum, I'd have an option for someone to donate every time I post an exhibition. It would be sort of like online "suggested donation" box, something that I'm not totally averse to having if the museum occupied a physical space. Or I could use it for membership fees like the $895 annual cost for access to Women's Wear Daily and its archives. WWD is a tremendously valuable resource that I could use when writing cosmetics history posts.

However (you knew there was a "however" coming), as with Kickstarter, Patreon isn't something I feel comfortable doing. I already put my exhibitions up completely for free, so why would I start asking for money now? If I lost my job and wanted to keep the blog going maybe then I'd consider it, but given that my exhibitions are in my house at the moment it would probably come off as "buy expensive makeup for me so I can take pictures of it and put it on a shelf in my bedroom."

The TL;DR version: I don't have the time, connections or social media presence to run a crowdfunding campaign right now and the success rate isn't high enough to be worth the crushing sadness I'll experience if my project isn't funded. Thus I am not attempting it.

What do you think of crowdfunding? What projects have you given to, if any? And just out of curiosity, would you contribute to a Makeup Museum fund or towards a book on contemporary cosmetics?

*I'm still bitter that with a single Tweet and one phone call, Inman was handed a check for $1 million by Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk in addition to the $1.3 million his project had already earned through Indiegogo. I guarantee there's no way the CEO of Sephora or L'Oreal would throw that kind of cash at me for my museum.

**I know I've mentioned it before and that the project was originally conceived as a silly prank, but it really burns my toast nevertheless.

Makeup Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning. I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

Since my last MM Musings post on what a permanent collection display might look like in an actual beauty museum, I've been thinking about ideas for special exhibitions. But I kept getting overwhelmed with the details of a specific exhibition's themes. After a while I realized my usual musings style wasn't going to work for a post on special exhibitions, so I changed tactics to bring you something much more interesting and enlightening than my usual reflections: an interview with Ashley Boycher, Associate Exhibition Designer at the Walters Art Museum here in Baltimore. Yes, I got to chat (email) with a real-life exhibition designer at one of the top museums in the country! Enjoy.

Since my last MM Musings post on what a permanent collection display might look like in an actual beauty museum, I've been thinking about ideas for special exhibitions. But I kept getting overwhelmed with the details of a specific exhibition's themes. After a while I realized my usual musings style wasn't going to work for a post on special exhibitions, so I changed tactics to bring you something much more interesting and enlightening than my usual reflections: an interview with Ashley Boycher, Associate Exhibition Designer at the Walters Art Museum here in Baltimore. Yes, I got to chat (email) with a real-life exhibition designer at one of the top museums in the country! Enjoy.

MM: What is the basic process of exhibition design? Does the curator tell you which pieces they want and you go from there? Who else do you work with besides the curator?

AB: Although sometimes exhibition ideas come from the public, certain museum trends, conservators, and/or museum educators, the seed of an exhibition is almost always planted by the curator, and the curator is academically responsible for the exhibition throughout the process. Once the seed is planted, the curator writes an exhibition narrative and begins to make a list of objects that s/he believes will best illustrate that narrative. Then there are lost of talks with conservators about which of the objects are in good enough shape and/or can be made into good enough shape for the exhibition given the timeframe. Also, when applicable, there are talks with registrars, who are responsible for the handling and logistics of moving and storing objects, and other institutions' representatives about the feasibility of bringing objects to our institution for the exhibition from other places. This happens with almost all large scale exhibitions and the negotiations with the other institutions often includes logistics about traveling the exhibitions to those institutions as well. In fact, grant funding is often dependent on the ability to collaborate with other institutions and travel the show domestically and/or internationally. Once many of these things are worked out, the curator and I begin conversations. This is usually about 18 months out from the exhibition opening. We do some preliminary ideation about object groupings and the look and feel of the show. During that time, the curator is also talking in a preliminary way with a museum educator about different didactic and interactive elements that might enhance the exhibition experience. At about a year out, the three of us come together and begin to really hash out the meat of the show. We also bring in representatives from the other museum divisions: IT, marketing, development, security, etc, when we need to collaborate on things like how we will advertise the show and what technology, if any, will benefit the exhibition message, both outwardly and inside the exhibition itself. All of the details come together in about 8 months, and for the last 4 months of the development process we are in production mode – labels being edited, graphics being printed, cases being built, walls being painted, etc – along with any straggler details that we miss beforehand, which always happens.

MM: Do you do some kind of prototype before the exhibition opens?

AB: It depends. Sometimes we're not exactly sure how a paint color will look in the space, so we'll slap it up on the wall and look at it for a few days and adjust where necessary. That is, if we have time. Often art is coming out of a space only a week before other art is supposed to go in, which means we don't always have the opportunity to do this. Other prototyping sometimes happens when we are trying out a weird or new display type. And we almost always prototype interactives, both low tech and high tech.

MM: Do you have experience with designing decorative object-based exhibitions and if so, how does it differ from designing exhibitions for other types of art?

AB: I've never designed a show that was purely dec arts objects, but they have been a part of shows i've designed. The new installation that opens here in October has lots of dec arts in it. I would say that in my experience one of the main differences is that many dec arts objects are heartier than other art, in better shape, and often made of less than precious materials, which means that conservation does not always make us put them under a vitrine. In this way they can help to create the look and feel of a space rather than just being purely on display. I suppose that was their original function anyway. 🙂

MM: What are some of the latest, cutting-edge developments in exhibition design?

AB: Well, unfortunately the latest cutting-edge development design aren't really happening at many art museums. Science museums and natural history museums are the ones that are usually on the cutting edge when it comes to design and technology. This summer I visited the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and one of their exhibitions had this amazing custom theatre system. It was made using custom craft carpentry, crazy projectors, and bit mapping. You can see a cool video about the making of it.

MM: What was your favorite exhibition you designed and why?

AB: That's a really hard question! The reason I got into exhibition design was because I was interested in too many different things to pick one thing to continue studying (I'm also just not that much of an academic eve though I really loved school). Working on exhibitions awards me the opportunity to learn about another fascinating different thing with each new project. So I guess my favorite is always whatever the latest project is. I suppose I have shiny thing syndrome.

MM: If money wasn't a factor, what would your “dream” exhibition be?

AB: When I was in graduate school, one of my big solo projects was an exhibition about the art, science, and history of tattooing throughout time and across the globe. I am fascinated by tattoos because they have so many different facets: cultural heritage, technology, biology, taboo, straight up beautiful artistry, the list goes on and on. I think a well planned and designed exhibition about tattooing could be interesting to just about everyone for one or more of these reasons. I'd love to be on a project like that.

MM: Do you have any ideas or suggestions regarding exhibitions that would have lots of small objects, i.e. makeup? I promise I'm not asking you to work for free – I'm just looking for any sort of general advice or tips off the top of your head!

AB: The hard thing about showing a bunch of small things is that the displays always want to look like retail rather than museum quality. My biggest advice would be to make sure you single out your best pieces. Put them on their own pedestals, maybe give them a bigger brighter pop of color, or a few more inches in height. Just make sure they actually stand out in a way that tells your visitor, "hey, you want to make sure you look at me and only me for a sec." If you want to do a display of a bunch of things together for impact or to get a certain point across, especially if it's several examples of one type of thing, make sure you save your 2nd and 3rd tier objects for those displays.

Thank you so much, Ashley, both for the peek into the life of an exhibition designer and for the invaluable advice!! (And I think we both have "shiny thing syndrome" – more literally for me).

Makeup Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning. I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

Today I'll be discussing what the permanent collection might look like if the Makeup Museum occupied a physical space (special exhibitions will be covered in the next installment of MM Musings.) Exhibition design is, of course, a behemoth topic and I don't expect to thoroughly describe every aspect of it as it applies to a beauty museum, but I thought I'd at least scratch the surface.

In looking at various museums and exhibitions online, it occurred to me that it's easier to start with what I don't want rather than what would be ideal. The following pictures are examples of displays that I personally don't find appropriate for beauty objects. I'm not slighting the hard work that went into these whatsoever, it's just that they will help me remember specifically what I hope to avoid in setting up a permanent display.

First up is labeling. I have discovered I'm a little very picky when it comes to communicating the information about each object. For the first example, while I love how neatly arranged all the objects are in rows in this 2008 robot exhibition, I can't see any labels. I can only assume they're in at the feet of each robot, but what about the ones on the top shelf? How is a visitor supposed to know what they're looking at? Obviously robots but I would want to know the name, year, and any other interesting facts.

(images from new.pentagram.com)

Even worse would be tons of objects crammed into one case with no labels. At least the above exhibition was arranged in an orderly fashion.

(image from whitehotmagazine.com)

I also don't belive that tiny numbers corresponding to the objects really count as labels. I loathe having to hunt for information. This labeling system doesn't engage visitors, it just frustrates them (or at least me). I'm more likely to walk away from a display if I can't readily view the information about each object. I know it doesn't require a lot of thought to match up the objects to the number. But it is an extra step, and given that I'm anxious to see as much as possible when I go to a museum, I hate wasting even one precious second having to look up an object I want to know more about.

(image from photos.hodgman.org)

(image from fairyfiligree.blogspot.com)

Even if the numbers are a good size, like in this 2012 Louis Vuitton Marc Jacobs exhibition, I still don't like not having all the information right near the object. It needs to be front and center.

(image from ibtimes.co.uk)

Second, I don't want a repetitive display. Below is a special exhibition devoted to Marilyn Monroe at the Salvatore Ferragamo Museum in Italy (Monroe was quite a loyal Ferragamo customer). This is a subject I'm definitely interested in, but I can already feel my eyes glazing over looking at that very long row of vitrines all set up exactly the same.

(image from dazeddigital.com)

Similarly, I like a good collection of (African?) masks as well as anyone, but I find this layout doesn't do them justice. One after the other against clear glass atop a concrete base strips them of their individuality.

(image from archdaily.com)

Now that I've shown some examples of what I don't want, let's look at some that I could see working for a beauty museum. I adore the design of Harrod's Perfume Diaries exhibition from 2010 and would love to have something similar as a permanent display. Everything is arranged chronologically, and the well-lit cases have niches for each item as well as individual labels. The white curved walls provide a modern, open airiness – something else I don't want is for the Makeup Museum is for visitors to feel like they're in some creepy old weirdo's cramped basement.

(image from thewomensroom.typepad.com)

Along those lines, I liked how the ads and objects were arranged in this perfume bottle exhibition. As you know, I frequently include ads in my exhibitions and I think this is a great way to do it. Again, I thought the crisp white backdrop worked really well – white would be a very effective surrounding for colorful makeup items.

(image from belepok.com)

It's no surprise that the exhibition displays that appeal most to me are for perfumes, since, after all, makeup objects aren't all that far off either in theme or size.

While this was a shallow dive into the vasts depths of collections display, I think it was very helpful for me to weed through and determine the basic aspects that I would want in permanent displays at the Makeup Museum, which are: 1. clear, easy-to-find labeling for every object; 2. differentiated areas or displays so that the objects' uniqueness can be emphasized; and 3. an open floor plan with lots of light.

Can you envision something similar to the perfume displays shown here for a physical Makeup Museum? And more generally, do you have any museum display pet peeves?

Makeup Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning. I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

"I dare you, I double dare you motherf*cker! Say curation one more goddammed time!"

Today I want to talk about curating and whether a beauty museum could have a curator in the traditional sense of the word.

The definition of curating has significantly shifted in recent years. Curating in the digital age takes on a vastly different meaning than that of one whose job it is to look after objects and arrange exhibitions exclusively in art museums and galleries. Nowadays it seems that everyone's a curator. From boutique owners to DJs to bloggers, curating has become synonymous with selecting or aggregating. There are even guides on how to curate web content. As the volume of information available online grew exponentially, there came the rise are self-appointed "curators" of websites and blogs who edit and select content for their readers. And as retailers struggle to compete, many of them turn to using "curated" to describe their selected merchandise.

Is there a problem with this? For some, particularly those who have been bona fide curators in the art world, yes. The backlash against the use of "curation" outside of an art context has been steadily growing. "You're not a curator, you're actually just a filthy blogger" is the title of an article by Awl editor Choire Sicha. According to Sicha, the use of the term is "a way for bloggers to distance themselves from the dirty blogging masses." He adds: "You are no different from some teen in Indiana with a LiveJournal about cutting. Sorry folks! You're in this nasty fray with the rest of us…you're a low-grade collector, not a curator…you're nothing but a secondary market for someone else's work." Indeed, Pete Martin, an author at the now-defunct arts journal New Curator rails, "You are, at best, a filter. You may make a name for yourself by excelling at some kind of selection process, but you are not a curator." And: "You should not equate yourself to an art exhibition curator just because you have a Pinterest account," writes Alex Ahn, co-founder of NYC art gallery Temp. As for the retail side, in an article for Macleans, vice-president of exhibitions and marketing at the Royal Ontario Museum Kelvin Browne stated: “The concept of ‘curating’ your life is just an excuse for high-end consumption…It’s pretending that buying stuff and putting it together is meaningful, but it’s not.” Back to Martin, who goes so far as to claim that "anyone calling themselves a 'curator' when it is clear that they are dealing in merchandise should have their thumbs removed." Yikes.

Given all of this, how wrong is it that I refer to myself as a "curator"? To clarify, I have never once meant the term to be serious as it applies to me. I mean it purely tongue-in-cheek, as a playful homage to real museum curators, who are what I aspire to be. In the "About the Curator" section I give myself a fancy faux title that uses the name of the founder of one of my favorite makeup lines – I'm just making a joke about the notion of endowed curatorships. Whenever I discuss curating an exhibition or myself as a curator, I hope it's clear that I'm kidding. I don't think I could be considered a real curator for a number of reasons. One is that I don't have formal training in the field. There are no official scholarly programs in cosmetics history, and while I'm flirting with the idea of going back to school for a degree in curatorial studies (this program is particularly tempting), I'm merely another self-proclaimed expert on the subject of makeup. Second, the fact that the Museum resides solely online and in blog form means that I am, indeed, just a "filthy blogger". Finally, it's…makeup. The items are not necessarily original or valuable, which is quite different than the one-of-a-kind objects a curator normally takes care of. (Of course, I still maintain that makeup belongs in a museum – see my very first MM Musings to read more about that topic.)

However, some believe that the two concepts of curating – the long-established, art museum meaning and the newer, social media-based approach – can peacefully co-exist, and that the democratization of the term is a good thing. "Ultimately, I think it’s fantastic for museums that museum words are making their way into the vernacular–it has the potential to give more familiarity to art museums for people who aren’t walking through galleries every day, which is of course a great thing," writes Chelsea Emelie Kelly, Manager of Digital Learning at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Online arts magazine Hyperallergic covered a panel at MoMA on the topic of curation and concludes, "It would be easy to argue that the significance and power of the museum curator has been undermined by the overuse of the word, but in reality it’s more true that the application of 'curating' to other disciplines has encouraged everyone to be more mindful of just what material they choose to pass on to their audiences, whatever the size or sector."

So…while I have officially disavowed myself of the notion that I'm a real curator, there are some signs that point to the contrary. Since "curate" comes from the Latin "curare" meaning to "care for", I might, just might, be able to pass as a curator. After all, I do lovingly care for all of the objects in the collection and oversee their preservation. In an interview for NPR, George Shackelford, the deputy director of the Kimball Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, says that curators "take responsibility for things…not just 'like' them." Secondly, while I don't have a formal degree in either curatorial studies or cosmetics history (the latter doesn't even exist), I'm just about as qualified as anyone else to run a beauty museum. I've worked for several major museums, have degrees in art history and cultural studies, and have been an avid user of makeup for over 20 years. Third,

I manage all of the museum's activities, from writing the exhibition labels to overseeing communications to organizing the collection. The ability to be involved in almost all aspects of museum administration is the hallmark of the modern curator. "They don’t simply organize exhibitions, they also have a hand in fund-raising and public relations, catalog production and installation," notes a 2010 New York Times article. This article also quotes a young curator from the Whitney Museum of American Art, who states, "The old-fashioned notion of a curator was that of a connoisseur who made discoveries and attributions…a lot of that work has already been done. The younger generation is trained to think differently, to think more about ideas.”

Finally, I arrange exhibitions. Now they might just be in my home and limited design-wise because of the space, but I do try to create an experience of some kind, something more meaningful and eye-opening than the objects would be if they were presented individually. This is also part and parcel of what modern curators do. According to Serpentine Gallery director Hans Ulrich Obrist, curating exhibitions today is much different. "Before 1800, few people went to exhibitions. Now hundreds of millions of people visit them every year. It's a mass medium and a ritual. The curator sets it up so that it becomes an extraordinary experience and not just illustrations or spatialised books," he writes in an article for the Guardian. He adds, "Exhibitions need not only take place in galleries, need not only involve displaying objects. Art can appear where we expect it least." I find these last two sentences to be particularly inspiring. If that's true, then perhaps I can consider myself a curator of sorts.

To conclude: I'm still not sure whether I'm a curator. My hunch is that most museum professionals would declare me an impostor, and I would be inclined to agree. But with all the new ideas surrounding curation today, it's plausible that the term used to best describe what I do could be curating.

If you made it this far, what do you think? Do you think managing this blog is, in fact, curating? How about if the Museum was a designated nonprofit and occupied a public, brick-and-mortar space?

Makeup Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning. I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

(image from someecards.com)

One of the issues that's foremost in my mind is finding a suitable location for the Makeup Museum, as I only have so much room at home. While I'm still nowhere near establishing a physical space for it, I love brainstorming possible places. There are plenty of galleries and other smaller venues where I might be able to do a temporary exhibition, but securing a permanent space is trickier. Ideally I'd have it in my adopted hometown of Baltimore. B'more is known for its quirkiness so I think a Makeup Museum would be a perfect fit. I've narrowed it down to several possible areas: Mt. Vernon (my hood, which would be very convenient for me and is also home of the Walters Art Museum), near the Inner Harbor (lots of tourist traffic), or somewhere in Station North. But rather than starting from scratch and renting or buying a stand-alone space, tacking on the museum to an existing one may be another avenue to consider. It may be easier to get funding for space for a new collection that will be attached to an already-established institution, plus since there are visitors I wouldn't necessarily have to lure them away to a whole different location – they're already in a museum they wanted to see, so why not stop by a little makeup-themed addition tucked away in the building?

In terms of these existing museums, I don't think it would jive well with the collections at either the Baltimore Museum of Art or the Walters (which is a shame as I live a block away from the latter.) However, I do see it possibly fitting into the American Visionary Art Museum, an institution that features "outsider" art and non-traditional art genres – work by prison inmates, exhibitions devoted to themes like "What makes us smile?", etc. A gallery devoted to cosmetics may be right at home there.

Finally, I was quite inspired by this post at Museum of the Future in which the author suggests alternative museum locations. It got me thinking that the Makeup Museum doesn't necessarily need to be housed in a traditional stand-alone space or as an afterthought to an existing museum. While it's already in a unconventional space (my home), it's obviously not available for the public to see in person, so it has to be accessible. Some of the venues the author came up with include train stations and airports, but I was most taken with the idea of having the collection, or at least an exhibition, on view in a mall or store. In fact, this notion has already happened in the form of Keiichi Tanaami's installation at Sephora. Could you imagine walking into a store and seeing an exhibition, similar to the ones I "curate", and then also be able to buy some of the collectibles you saw on display? Another possibility is also one that's been done with success – have an exhibition at a makeup expo, like the Makeup in New York show I visited back in September, or the Makeup Show LA's upcoming exhibition on Kevyn Aucoin.

I'm not sure how I would even begin to approach people at these various places, especially since it would be a most unusual conversation and I'm not particularly adept at networking (or at any human interaction, really). Any suggestions are highly welcome.

Would you rather see the Makeup Museum in a space by itself, as part of another museum or in another venue altogether (like Sephora or a department store?)

Makeup Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning. I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

image from museumheygirl.tumblr.com

Taking into account the storage issues I discussed in the last installment of MM Musings, today's post will focus on the recent notion of "visual" storage, in which some or most of a museum's stored pieces are accessible to visitors, and how this concept could be applied to the Makeup Museum. Typically, only about 5%-10% of a museum's entire collection is on display at any given time. (This is certainly true of the Makeup Museum as well.) Visual storage allows visitors to see much more of the collection, and without being directed to follow a certain path the way they would in an official exhibition. Several museums have adopted this practice, including the Brooklyn Museum, the Clyfford Still Museum, LACMA and the Met.

Visible storage allows museums to "democratize" their collection by moving previously unseen items out in the open and making them available to the public. In this way curatorial and director opinions about what should be displayed are somewhat overruled. Says art blogger Lindsey Davis, "If the works aren’t being used in a particular themed gallery, that doesn’t mean your visitors should be kept from them, especially since it’s just museum management’s decision to hide them away." Additionally, it's beneficial for museums to offer visible storage to provide a more transparent, open relationship with their audience instead of having visitors believe museums are "hoarding objects in a dark room", as LACMA Director Michael Govan puts it. Adds Joanne Heyler, director and chief curator of the Broad Museum, "How in a building can we make it clear to visitors that storage and conservation are a core part of the museum's function?" In this way visitors get a glimpse of how objects are stored and can understand that they are not actually shoved haphazardly in a dark basement, which might foster a better sense of trust in the institution – helpful for securing those all-important donations.

(image from brooklynmuseum.org)

But why is visible storage also popular with visitors? It goes back to the idea of democratization – people can look at objects that speak to them, rather than being told what pieces they "should" be looking at. There's a freedom in exploring visible storage that's somewhat lacking in a curated exhibition. "One of the major appeals of the visual storage concept, [LA Times reporter Jori] Finkel suggests, is its open-ended, choose-your-own-adventure style of presentation, which allows visitors to seek out objects they find interesting and compelling with relatively little curatorial direction, which she likens to the process of searching for images online. 'What we’ve found is that people love visible storage,' [Brooklyn Museum Director] Arnold Lehman said. 'They feel like they’re on their own, not as directed as they would be in galleries, and they get to discover things. It’s like a treasure hunt.'" In other words, it functions quite similarly to the Internet (or perhaps more closely, Pinterest) where one can freely wade through hundreds of thousands of images and select those that appeal to them.

Indeed, this fits the experience of Hoarded Ordinaries author Lorianne DiSabato, who shared her thoughts on stumbling across the visible storage section at the Met. "Had I but world enough and time—had my feet not been aching from an entire day of Museum-rambles—I could have easily spent hours looking at this stunning array of objects—an embarrassment of riches—with only curiosity rather than curatorial captions to guide me. Without the narrative storyline of an curated exhibit to tell viewers what they 'should' get out of these objects, museum goers are left to sift through the troves on their own, picking and choosing their own masterpieces from the aisles."

(images from metmuseum.org)

The above pictures from the Met, I think, are similar to what the Makeup Museum's visible storage would look like if there was a public location. There's no question that I would have visible storage; the only reason I don't keep more things out on display currently is lack of space! I would love for visitors to see all the wonderful objects in the collection outside of permanent or special exhibitions. Visible storage, where items tend to be stored more closely together than in the regular galleries, would be especially appealing to cosmetics junkies. "Haul" and "stash" pictures are quite popular in the makeup world (as of this morning, googling "makeup haul pic" yielded 8,440,000 results!), and the visible storage in the Makeup Museum would resemble these photos in that it would feature large groups of makeup items in individual cases, organized either by brand or by type (similar to what I do for my "group portraits" but with labels.) Basically, it would much more aesthetically pleasing than the current storage situation, which is dire.

What do you think of visible storage in general? And would you like it if the Makeup Museum offered it?

Makeup

Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum

topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my

vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me

think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual

organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning.

I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a

museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

I bet you're wondering where the Curator keeps the Makeup Museum's collection. (At least, I hope all two of my readers are curious.) So today's installment of MM Musings is devoted to the topic of storage.

No museum can really escape the issue of where to store its collection; it's not as though curators and directors can simply toss pieces into the garbage if they don't want them anymore. While museums do regularly deaccession some of their works, this is not the most efficient way to make room for more items. However, the bigger storage issues museums face relate to organization and security, not so much lack of space. When a public institution such as a museum is planned, obviously the people behind it ensure the location they choose has enough room for a growing collection. Some museums also are able to obtain grants for either off-site storage spaces or additions to the current location should their collection outgrow the existing storage space.

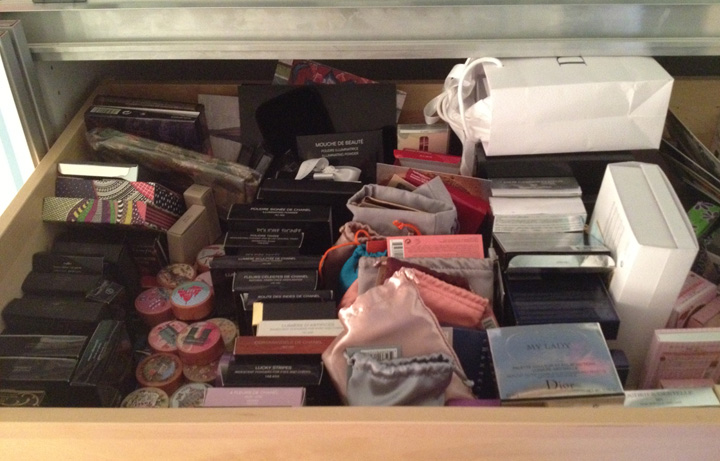

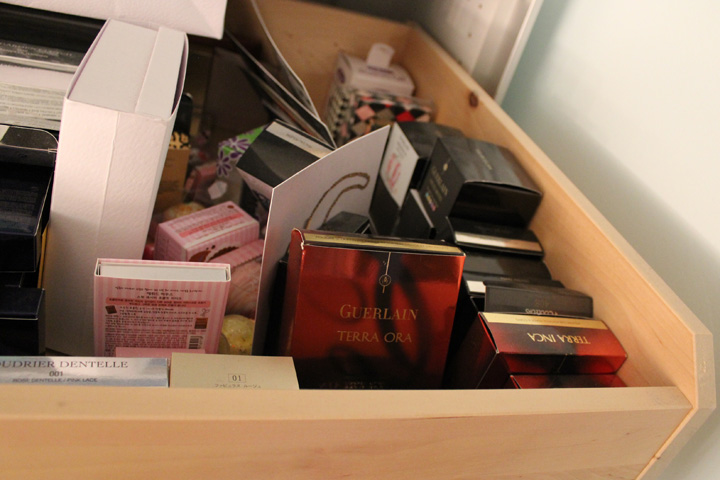

But for a private collection that grows quickly such as the Makeup Museum's, finding enough space is definitely a challenge. While makeup items tend to be small, I'm adding things at a very fast pace so my designated storage spaces fill up rapidly. And since the Museum does not yet occupy a public space, I can't exactly jump on the "visual storage" bandwagon that's so popular these days (my next MM Musings post will cover that.) Everything is stored at home in several different spots.

Now I will take you through the dark underbelly of the Makeup Museum and see if you can help me come up with a storage solution that doesn't involve off-site space or deaccessioning some of the collection (the horror!).

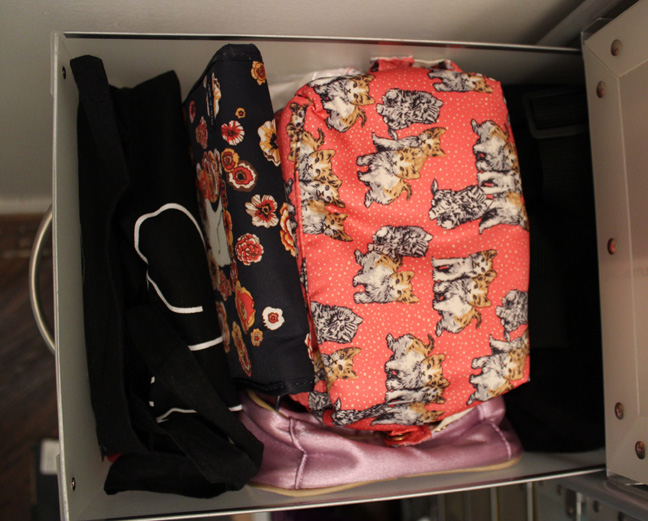

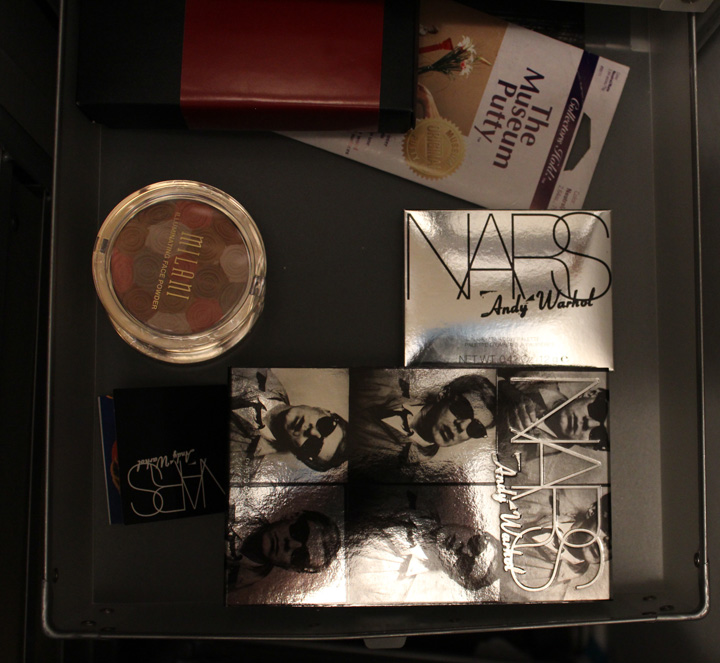

First I'll take you through the makeup room. Actually it's technically a master closet, but since most of my makeup is stored there, including the stuff I actually use, I refer to it as the makeup room. (This is also the room the husband built to convince me to move in…he had NO idea what he was in for.)

The closet and drawers are from Ikea, the Stila poster is from the kind salespeople at the Columbia Mall who let me take it. I was upset at the thought of it being destroyed after it was taken down so I asked if I could have it when they were done with it.

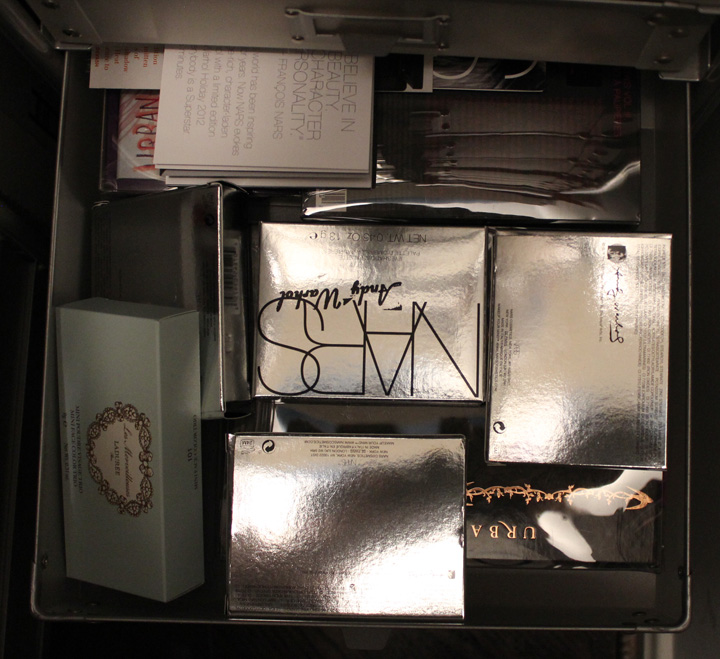

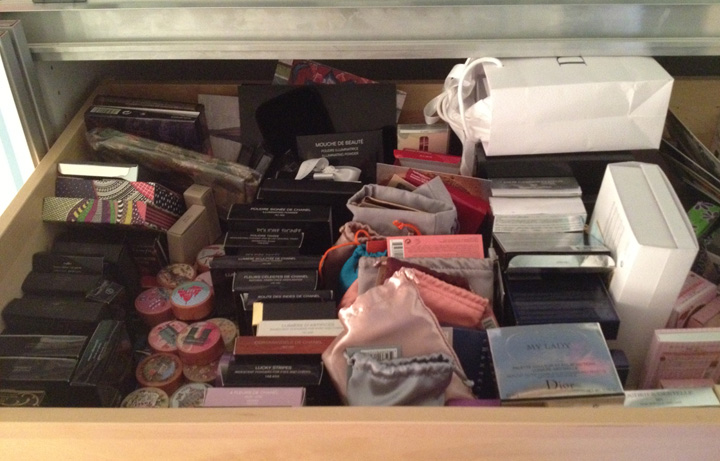

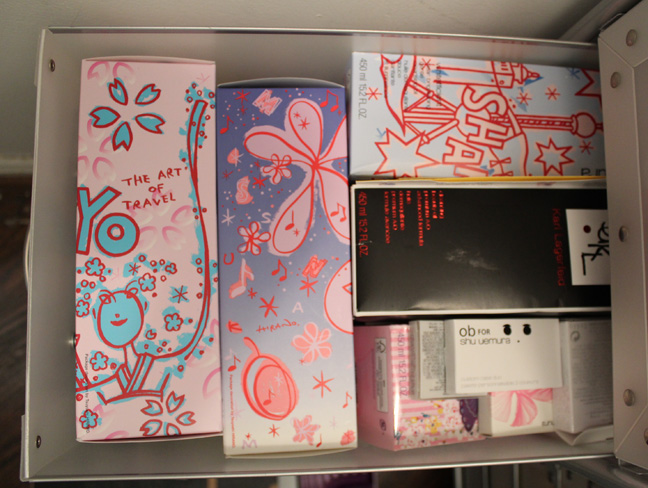

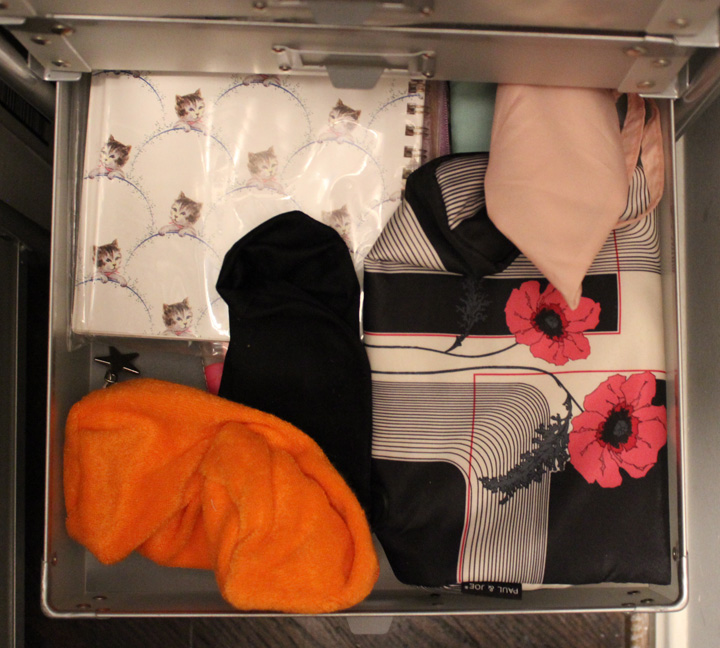

Here's the drawer where I store Paul & Joe and Stila. I store these brands here because they fit better here than they do in other drawers – you'll see why shortly.

Hey, Mummy Babo! Get out of there! I guess the little scamp couldn't resist photobombing my storage pics.

The very top drawer stores makeup from brands A-K. This was nearly impossible to photograph because it's up so high – even on a ladder I couldn't get a good picture.

It starts with A's (Anna Sui, Armani) on the left and continues to the right.

The rest of the drawers hold clothes as well as my stash (the makeup I wear rather than display), and on top of the closet are storage tubs holding miscellaneous seasonal items – summer shoes, mini Christmas tree, etc. So unfortunately I think the rest of that closet is off limits in terms of making more storage for the Museum.

The rest of the collection is stored in another closet, although this one is much smaller and regrettably, probably the ugliest space in our home. It's in a weird little niche off a hallway near the bedroom and we keep all kinds of random stuff in there – flashlights and other tools, cleaning supplies, physical therapy/fitness items, etc.

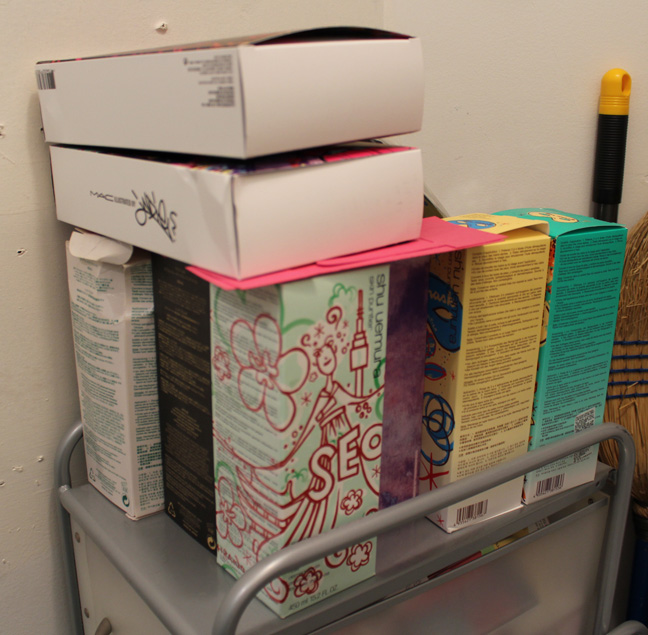

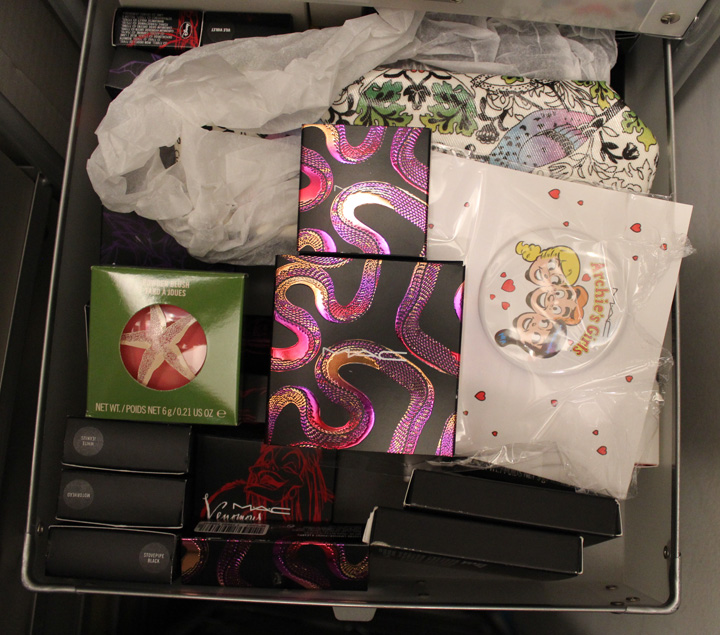

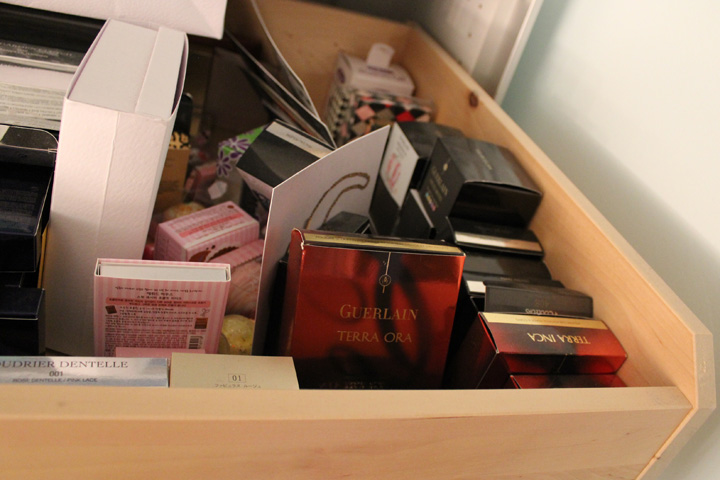

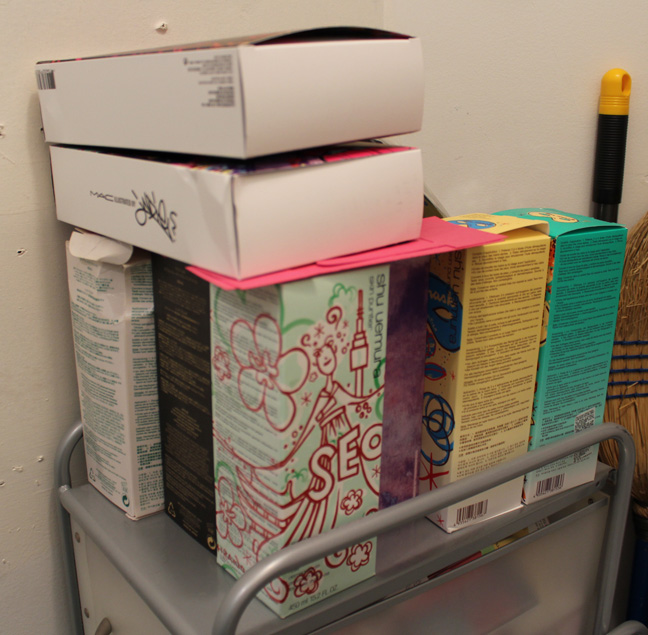

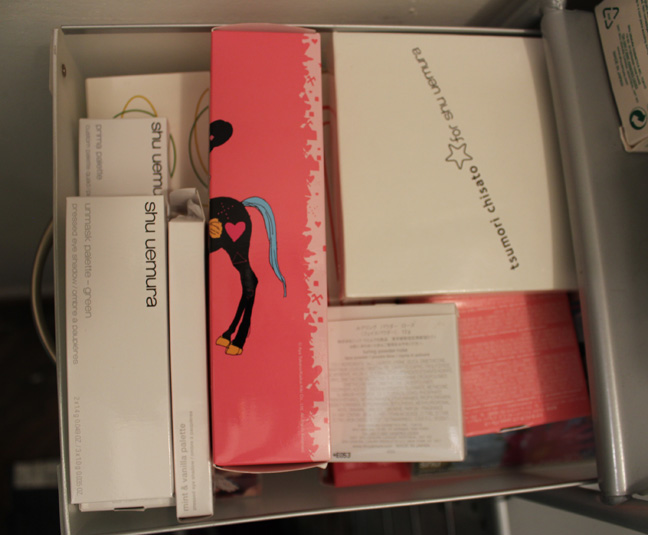

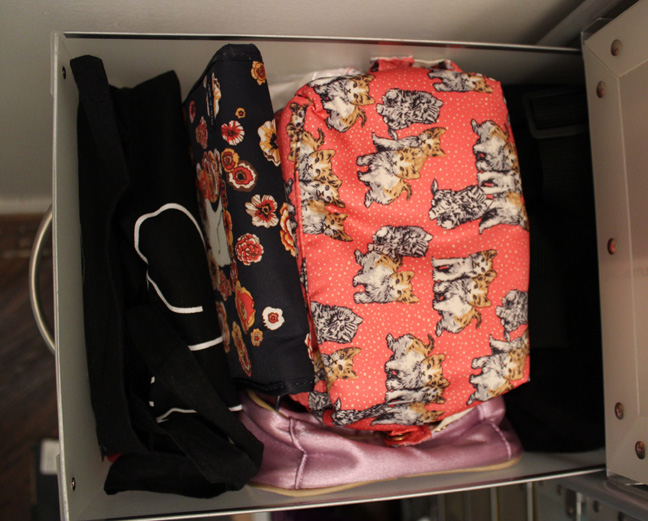

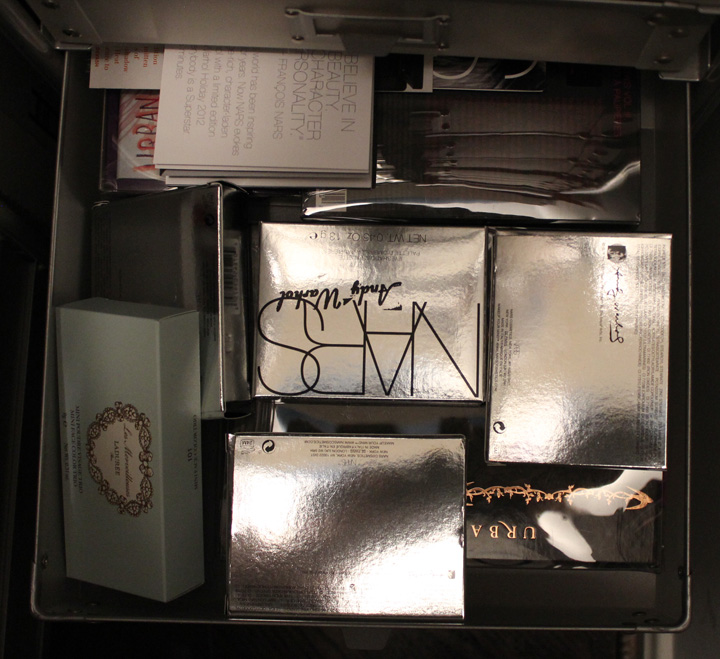

I think these drawers are also from Ikea. Originally the drawers were designated just for Shu Uemura, but I had to stack some MAC bags on top.

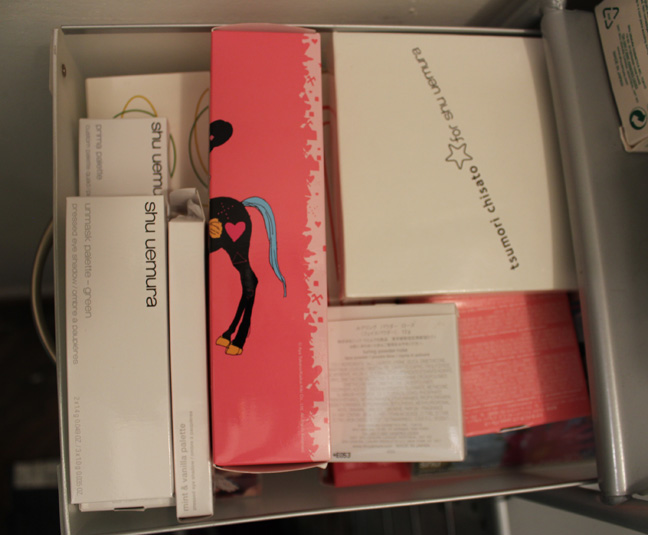

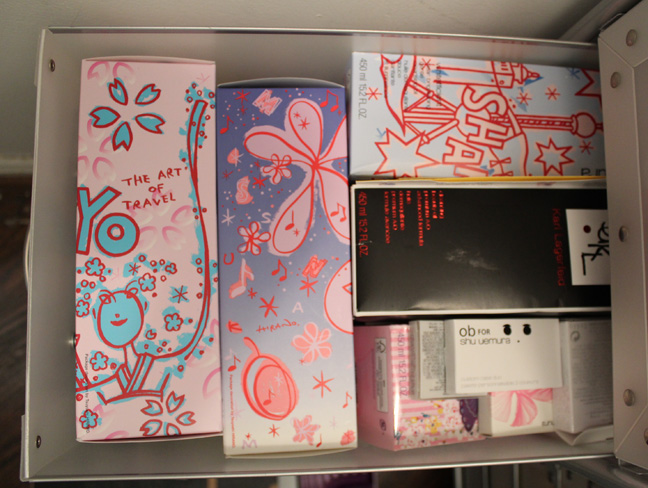

Now the individual drawers, which as you can see, are pretty full.

This drawer has some Paul & Joe bags that couldn't fit in with the other Paul & Joe stuff, along with some other makeup bags. The black one in the front of the drawer (on the left in the pic) is a tote from the NARS Melrose boutique, while the purple one next to the red Paul & Joe kitty bag is from Chantecaille.

The last drawer contains postcards.

Another set of drawers sits to the right of that set. I cleared off the top but normally we have workout stuff (weights, etc.) sitting on it. Why, hello Swiffer!

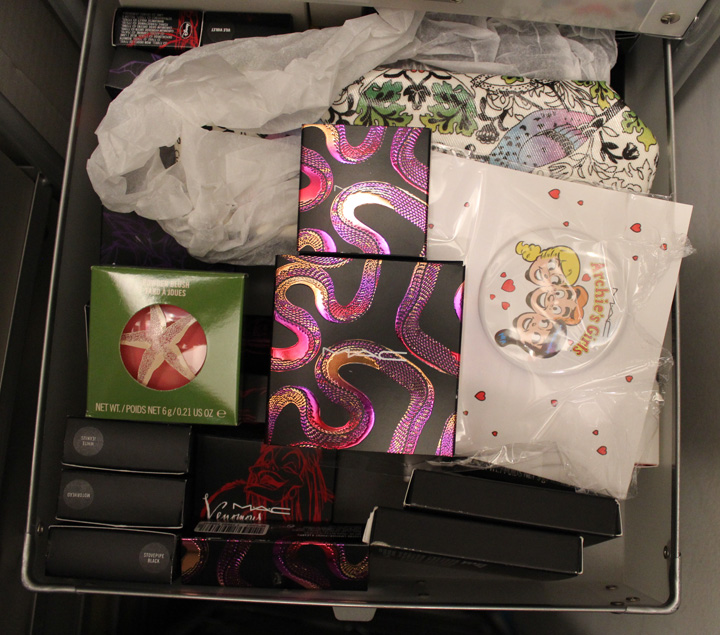

The first drawer has totally random stuff from all different brands – brands that aren't well represented in the Museum's collection so far, i.e., ones that I don't need entire drawers for yet.

The rest of the drawers contain all my LUSH bath goodies.

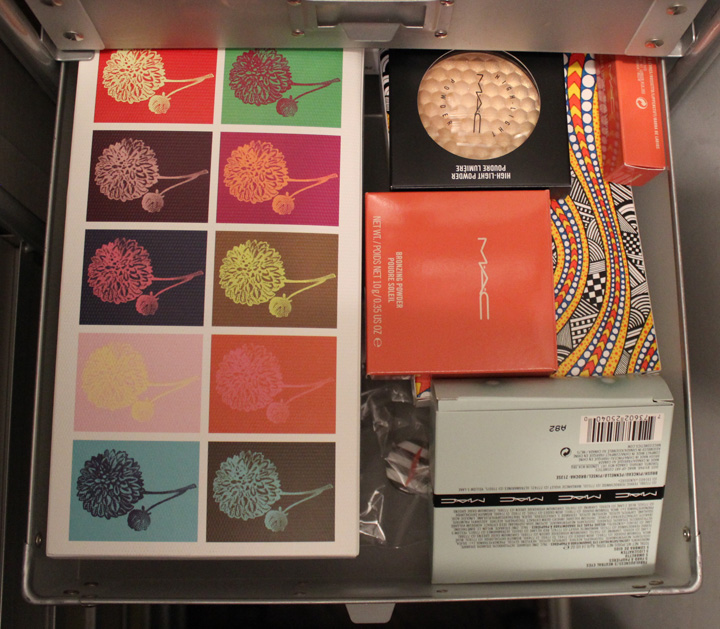

Finally, there's another cart of drawers all the way in the back. I've resorted to putting more Paul & Joe stuff on top.

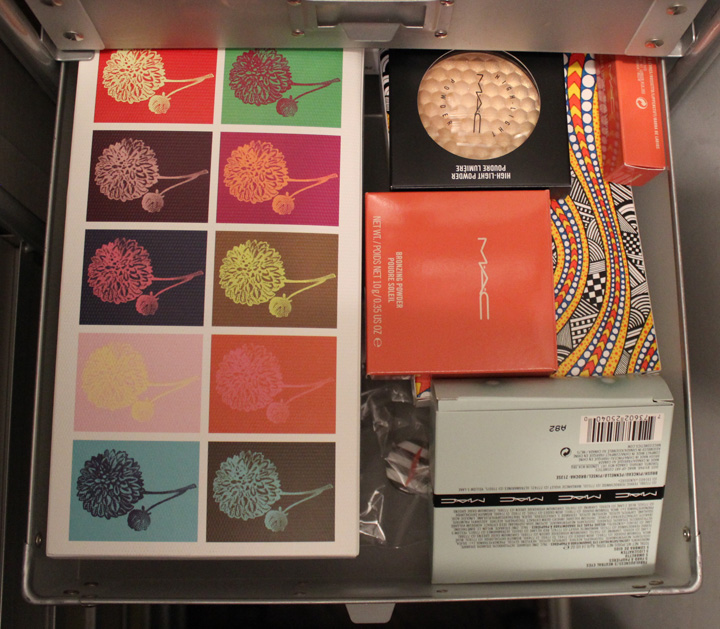

First drawer contains the L's – Lancome and Laura Mercier.

Then we move into MAC.

Here's where the organization really falls apart. I think this drawer originally just had Too-Faced palettes, but with MAC's constant limited-edition offerings I had to put MAC stuff in here too.

The rest of the Too-Faced collection and some Tokidoki:

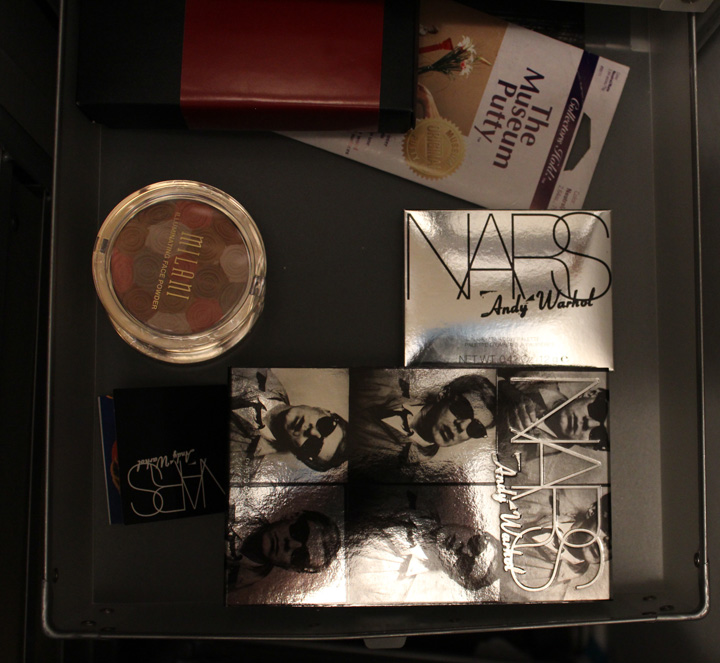

Then, the bottom-most drawers, which I have trouble reaching because this cart sits behind another cart where we keep home repair stuff, I ended up shoving NARS stuff in there, along with more random items (Milani, Laduree, Urban Decay). Clearly this is no longer alphabetical. I think I did it this way because I wasn't expecting NARS to ever have LE items, so I just went straight from MAC to Too-Faced and instead of moving NARS up one drawer and the Too-Faced stuff down, I just put them in here. Lazy I know.

Then, finally, more bags and other memorabilia.

So…any suggestions how to make more room besides getting rid of things or moving them off-site? In looking at that second cart, I think I may have to strip it of the LUSH items and move them somewhere else – I can probably put them in one larger bag somewhere, there's no need for them to be spread out in the drawers. Another option is to attempt to put some things into the storage tubs on top the of the closet in the makeup room, but that really isn't easily accessible. The stuff that's up there now are all things I need only once or twice a year, but with the Museum's exhibitions happening at least 4 times a year and me constantly putting away things that aren't on display I need easier access.

Unfortunately that's all I can think of at the moment. We either need to move to a bigger house or I need to get a public space!

Thoughts? (Other than "you have too much makeup")?

Makeup

Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum

topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my

vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me

think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual

organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning.

I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a

museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

In this installment of MM Musings, I want to discuss how the Museum might be able to attract a broad audience.

In this installment of MM Musings, I want to discuss how the Museum might be able to attract a broad audience.

Generally speaking, museums aim to reach the widest audience possible. Not only is it a part of their mission to provide educational and cultural opportunities and information to all citizens, a bigger audience translates to more revenue. For museums with large, more general collections, getting people from all walks of life is a challenge, but not nearly as difficult as it is for a small-sized museum with a collection that appeals to only a tiny segment of the population, i.e. the Makeup Museum. How do I get people who aren't really interested in cosmetics in the door? Should I even care about attracting a wide audience or simply cater to beauty addicts?

I'm going to answer the second question first. On the one hand, I feel like I should care about getting through to those who have little to no interest in makeup. I feel as though museums, even niche ones, have a duty to educate and provide intellectually stimulating experiences to everyone. I would hate to see women dragging their incredibly bored husbands/boyfriends around – there needs to be something for them too.* And of course, there's the financial standpoint – more visitors equals more funding.

On the other hand, dreamer that I am, if the Makeup Museum has even one fulfilled visitor I'd be happy. Mission accomplished! I admit there's a selfish angle to this too. I want to show off my collection because I personally find it to be fantastic, and because I like it so much, I sort of don't care how others feel about it. It's cool to ME and that's all that matters. Which is awful and I feel guilty for writing that. Plus, no foundations would provide grants for "pet projects" which, I guess the Museum would be if I'm not willing to prove that it performs an educational or cultural service for the public. "Give me money because I think my collection is awesome" isn't the best approach.

Therefore, if the Museum ever does occupy a physical space, I will endeavor to get anyone and everyone to visit. As I said previously, this can be hard for even large museums with huge collections that would appeal to a broad range of people. So audience diversity would be particularly tricky for a niche museum.

However, the plethora of niche museums makes me think that it is possible to provide programming for all audiences. This article profiling the recently opened ABBA Museum in Sweden particularly gave me hope. "[We] think the new ABBA museum could withstand the test of time even

with its highly specific subject matter. It would have been easy to

treat the band as a curiosity of the past and merely showcase old

costumes and videos while the band’s comprehensive music catalogue

filtered through the loudspeakers. But the museum designers have made

what could have been a kitschy nostalgic relic of a space into something

modern and fresh, thanks to interactive elements and high-tech

showpieces that will appeal to even kids and casual fans." The article then highlights the museum's cutting-edge interactive features. My vision for the Makeup Museum is exactly this. While I plan on some room for vintage items, it won't have that musty, "cabinet of curiosities" feel – I will link them to contemporary cosmetics via specially-themed exhibitions and/or create some highly advanced interactive components of my own.

Additionally, I think cosmetics just might be an odd enough topic to reach a wide audience even if they're not usually interested in makeup. For example, I'm not a dog person at all, but would I go see Foof (The Museum of the Dog) in Italy? Of course!

(image from details.com)

I'm terrified of surgery and the unconsciousness that's a result of anesthesia, but I would totally visit the Anesthesia Heritage Centre in London.

(image from visitlondon.com)

It's the sheer novelty of these places that draws people in, and if I may toot my own horn, I think I'm creative enough to make cosmetics into an appealing theme for a museum. As long as it's got a modern, dynamic feel vs. a static one (which, admittedly, how it is now – the objects just sit on shelves), I think it would be successful at reaching a wide audience. The biggest hurdle as I see it would be how to handle the gender issue. Other niche museums, while devoted to a an odd topic that may not attract everyone, have the advantage of not being quite as gender-specific as a cosmetics museum. By and large makeup is still viewed as a women's sphere, so the challenge is to draw in the guys without making them feel like they're out of place (or for the really macho dude-bros, losing their masculinity – heaven forbid!). This is where creative programming and exhibitions come in. I would have a permanent exhibition of men's grooming and yes, even cosmetics (more on that in a later post), along with gender-neutral exhibitions – say, makeup used in film.

Given how much I struggle just to get people to visit the Makeup Museum online, perhaps I shouldn't be so optimistic that a public space would engage a diverse audience. Having said that, the Museum in its current form is pretty different from how I would manage it in real life, and I think even overhauling the website to make it more museum-like and less of a blog would go a long way in attracting visitors outside of those who are makeup-obsessed.

Thoughts?

*I realize that's a rather sexist way of looking at things – there are guys who are interested in makeup and women who couldn't care less. I was just trying to give an obvious, relatable example of who would be more likely to enjoy their visit and who would rather gouge out their own eyes than go to a museum devoted to makeup.

Makeup

Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum

topics as they relate to the collecting of cosmetics, along with my

vision for a "real", physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me

think through how I'd run things if the Museum was an actual

organization, as well as examine the ways it's currently functioning.

I also hope that these posts make everyone see that the idea of a

museum devoted to cosmetics isn't so crazy after all – it can be done!

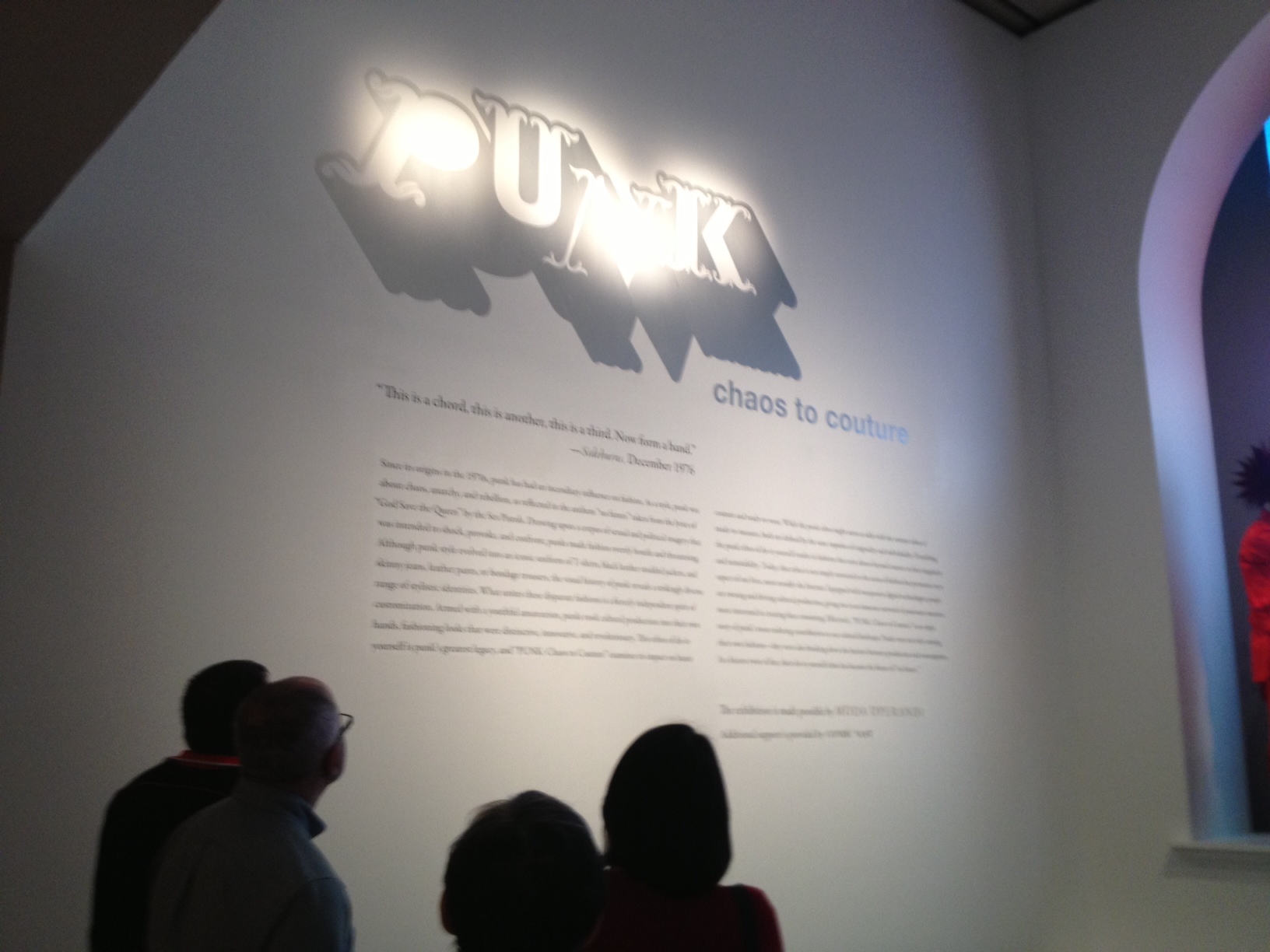

Above are two pictures I snapped with my phone (flash off, of course) at the Metropolitan Museum's "From Chaos to Couture" show back in May. Promptly after I took the second one, a guard came up and yelled that no photography was allowed. He literally raised his voice at me, his face turning purple, nostrils flaring. I was not a happy camper, as 1. there wasn't a sign posted at the beginning of the exhibition stating that pictures were prohibited; 2. I paid the full "recommended" donation AND bought the exhibition catalog AND a t-shirt, not to mention I took time off work specifically to travel up to NYC to see the show – after I spent that much money at their museum, I think I'm entitled to take a few cell phone pics for personal use; and 3. There was no reason for the guard to get so furious and make a scene – he could have just quietly, politely informed me that photos weren't allowed. From his reaction, you might have thought I was snatching the clothes off the mannequins and trying them on myself.

This anecdote raises not only my blood pressure but the question of whether I would allow photos in the Makeup Museum if it occupied a physical space. Obviously I'm leaning towards the affirmative, but I will explore both sides of the argument.

First, let's take a look at why some museums prohibit photography of any kind. In the "old" days, i.e., when I was a wee lass studying art history in college over a decade ago, most museums allowed photography as long as you took the flash off your camera. The bursts of bright light and heat damage the pigments of a painting, helping them fade and deteriorate much more rapidly than they would otherwise. However, in recent years I feel as though there's been a significant shift in museums' photography policy. It seems that most museums now ban all photography. Their top reasons:

1. Taking photos creates even more congestion than there normally would be. With the ubiquitousness of smartphones, it's so much easier than it was previously to take a quick picture of something that catches your eye, which in turn equals more people stopping to take pictures.

2. Visitors are "stealing" from the museum by taking their own pictures rather than buying a postcard or exhibition catalog from the museum store. Picture-taking also reduces income because people will post these pictures online and this will result in fewer visitors – the rationale is that if people can access the image online, they won't have a reason to visit the museum in person.

3. Legal matters. Most museums don't own every piece of artwork that's on display. If there's a special exhibition that has works on loan, the museum who loaned the works may not allow photographs of them. Additionally, there's the issue of copyright infringement (read this balanced article on museums and photographing copyrighted pieces.)

4. It's easier than saying "no flash photography". I have no evidence to back this up, but my hunch is that museum directors simply decided to ban all photography due to people not knowing how to turn the flash off their camera or ignoring the rule of no flash.

Some bloggers, rather pretentiously, I might say, add their own ludicrous reasons: it's "tacky" and turns museums into tourist traps; the clicking of the camera is distracting to those trying to quietly appreciate the art; it cheapens the museum experience by turning the works of art into mere photo props – people aren't looking at the art but rather only an opportunity for a picture.

Now, I want to counter these arguments and explain why photos in museums should be allowed. (I still agree that the flash needs to be off – the camera sound isn't distracting but the light definitely is, and it could hurt the art).

1. Rooms with popular works of art and exhibitions will always be crowded. The taking of pictures is the least of the problems with trying to get a glimpse of, say, the Mona Lisa. I visited the Louvre and let me tell you, there were just as many people crowding around to view it as there were people taking pictures. During the same trip when I went to the Musée d'Orsay, which strictly enforces its no-photography rule, I could barely see the work I was most excited about (Manet's Le déjeuner sur l’herbe) because of all the people. They were surprisingly well-behaved – no one was attempting to break the photography ban – but the sheer volume of people meant you just had to wait until there was a small clearing to actually get a decent look at the painting. Prohibiting photography is not going to lessen congestion.

2. Museum store merchandise doesn't always meet the needs of visitors. During my Met visit, I bought the catalog but still took pictures of the exhibition. You know why? Because I wanted to remember the layout of the rooms and re-read the exhibition label text on the walls – things that aren't included in the catalog. Also, people might want a shot of a particular piece that has meaning to them but because it's not a hugely popular work, there is no postcard or book with the picture available, and even the museum's website doesn't provide an online image. Another example I can provide is when I went to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. I fell in love with all the stunning artifacts in the jewelry cases but did not take pictures, since there was a sign at the front of the gallery saying they were prohibited. Oh well, I thought, I'm sure all this amazing stuff is in a book at their store. But when I went to the store there was no jewelry collection book. This point is especially important to keep in mind for the so-called "tacky tourists" – I can't get on a plane and visit that jewelry exhibit whenever I please, so I would appreciate having a nice big book to remember it by, and if they don't sell one, I would at least like some crappy pictures I took with my phone. It's better than nothing! Finally, a postcard of the work of art you're interested in doesn't have you or your loved ones in it, nor does it fully capture a visitor's memory. The reason people take pictures of themselves or their families and friends standing with a piece of art is because they want a reminder of that moment, of being able to look back and say, "Hey, I saw my favorite work in person! There I am standing next to it. How cool!" Books, posters, postcards, etc. that you can buy in a store just don't do that. I also suspect that most museum-goers will still buy store merchandise even if they have their own pictures. It's meaningful to have pics you took yourself, but many visitors also love the high-quality, glossy images that only store merchandise provides.

3. Legal matters. Okay, I can't really argue with this. If a museum allows photography of a work that's on loan by a museum that doesn't permit photos of that work, the borrowing museum could get in a lot of trouble. A lawsuit could shut it down in one fell swoop. So I understand museums need to err on the side of caution. However, they need to make it very clear to visitors that some pieces or exhibitions are off-limits for photography. In the case of my experience at the Met, would it have killed them to put some signage up indicating that taking pictures of that particular exhibition was forbidden? If they had done that, most people, myself included, wouldn't attempt to take pictures. Thus the guards wouldn't have to spend all their energy yelling at people taking pictures – they could protect the art from real damage, like the attack that recently occurred at the National Gallery in the UK. I don't think it's coincidence that this museum doesn't allow pictures – the guards were probably too busy screaming at hapless tourists to notice a man trying to deface Constable's The Hay Wain.

4. The times, they are a-changin'. We are rapidly heading in the direction of an image-based culture. While I don't think text will ever be fully replaced by images, it's important to accept the how much sway social media platforms like Instagram and Tumblr have both in the art world and society at large. From ArtNews: "As a culture, we increasingly communicate in images. Twenty years

ago, a museumgoer might have discussed an interesting work of art with

friends over dinner. Today, that person is more likely to take a picture

of it and upload it to Facebook…or perhaps that museumgoer might

remix his or her photo with other visual elements and transform it into

something new. Every day, users on image-sharing sites such as Tumblr

create their own diptychs, collages, and themed galleries devoted to

everything from ugly Renaissance babies to Brutalist architecture. This transformation in the way in which people digest visual

stimuli—not to mention the rest of the world around them—is something

that Harvard theoretician Lawrence Lessig has described as a shift from 'read-only' culture (in which a passive viewer looks upon a work of art)

to 'read-write' culture (in which the viewer actively participates in a

recreation of it). The first step toward recreating a work of art, for

most people, is to photograph it, which, ultimately, isn’t all that

different from the time-honored tradition of sketching." Basically, museum directors can't ignore the impact of modern-day picture-sharing. Instead of trying to fight it and eliminate picture-taking completely, museums need to use new social media and technology to their advantage. One blogger sums it up best with his experience visiting the Grammy Museum, which bans picture-taking:

"I snapped some photos when nobody was looking. And I’m hardly

alone – a Flickr or Google search will confirm that hundreds of pics of

this place are online, despite their photo ban. The lesson is this: With all the tiny digital cameras these days and even cell phone cameras, people will take photos in your establishment and they will end up on the Internet, whether you like it or not. There’s no use trying to fight it. To me, museums that still ban photography are like record companies

in the late ‘90s that opposed downloading. Instead of embracing the

technology and using that free publicity to their advantage, they

stubbornly stick to an antiquated view that winds up being a lose-lose

scenario for everyone involved."

Finally, I've already countered most of the concerns various bloggers have regarding museum photography, but I will address a couple more here. I don't think allowing pictures "cheapens" the museum experience at all, nor does it prevent people from fully engaging with the art. The author at the Everywhereist asks, "If everyone was snapping photos all around him, do you think Cameron [in the film Ferris Bueller's Day Off] could have had his moment in front of Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grand Jatte?" The scene she is referring to is from a movie. I'm sure the museum closed the gallery to the public that day in order for the camera crew to get the scene without anyone interfering. Plus Cameron Frye is a totally fictional character and thus, so are his "moments". Bottom line: it's a moot point.

The Grumpy Art Historian says that "People taking photographs in museums is distracting. Even non-flash

photography can be a distraction, with those annoying electronic shutter

sounds." If that's the most annoying thing about visiting a museum to you, consider yourself lucky. Personally, I find the hordes of hyperactive schoolchildren who don't understand why they're there, the occasionally inane comments loudly expressed by other museum-goers, or *shudder* people who actually try to TOUCH the artwork, to be far more irritating than the tiny click of a camera. Eliminating cameras will not, unfortunately, cut down on other obnoxious behavior.

The last article I want to address is one that appeared at the Guardian. The author writes, "I was being jostled and pushed not by people anxious to get a better view of the art on show in one of the world's great museums, but by mobile phone owners rudely trying to ensure no one blocked their

desired camera angle. They were there not to see and be inspired by

artists of genius, but to take snaps to prove they were there." First of all, for really popular works of art, people get jostled all the time – and not just by other people taking pictures. Once again, prohibiting photography will not reduce crowds or rude behavior. Secondly, who cares if they wanted a picture just to prove they were there? Personally, I'd be flattered if people visited the Makeup Museum only to brag about it but not appreciate any of the items. At least I got them in the door, and that's what matters.

My rough plan for the Makeup Museum's photography policy consists of the following:

1. Allow photography for the general public for non-commercial use, but no flash or tripods will be permitted. Additionally, a "one and done" policy will be in place, where if someone takes a picture

with their flash on, they get a warning, and if they do it again they

get thrown out of the museum. While it's still debated as to whether today's cameras have as damaging a flash as the flashbulbs used in older cameras, I don't want to take any chances. Most of the Makeup Museum's collection consists of delicate powders whose colors can fade quickly without being hastened by flash photography.

2. Allow professional photography for bloggers and other members of the press, but they will need to pay for a press/photographers' pass. This idea has been implemented with great success at the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

3. As for copyright and intellectual property, those are non-issues. All of the objects in the collection are owned by me at the moment and were purchased when they were for sale to the public. None are on loan from another person or institution.

What do you think both of my proposed outline for photography and non-flash photography in museums in general? Have you ever gotten yelled at by a hostile guard for taking a picture, not knowing they were banned?

A while back the excellent fashion blog Worn Through had a post questioning whether fashion curators needed to also be designers, or at the very least, know how to sew. It got me thinking whether the same conundrum would face a beauty curator, i.e., does one need to be a professional makeup artist to oversee a beauty museum?

A while back the excellent fashion blog Worn Through had a post questioning whether fashion curators needed to also be designers, or at the very least, know how to sew. It got me thinking whether the same conundrum would face a beauty curator, i.e., does one need to be a professional makeup artist to oversee a beauty museum?