Despite my art history background and general love of art, I am less than eloquent when writing about it. Nevertheless I will continue soldiering forward with the Museum's Makeup as Muse series, the latest installment of which focuses on the work of Gina Beavers in honor of her recent show at Marianne Boesky Gallery. Beavers' practice encompasses a variety of themes, but it's her paintings of makeup tutorials that I'll be exploring. Since I'm both tired and lazy this will be more of a summary of her work rather than offering any fresh insight and I'll be quoting the artist extensively along with some writers who have covered her art, so most of this will not be my own words.

Born in Athens and raised in Europe, Beavers is fascinated by the excess and consumerism of both American culture and social media. "I don't know how to talk about this existence without talking about consumption, and so I think that's the element in consuming other people's images. That's where that's embedded. We have to start with consumption if we're going to talk about who we are. That's the bedrock—especially as an American," she says. The purchase of a smart phone in 2010 is when Beavers' work began focusing on social media. "[Pre-smart phone] I would see things in the world and paint them! Post-smartphone my attention and observation seemed to go into my phone, into looking at and participating in social media apps, and all of the things that would arise there…Historically, painters have drawn inspiration from their world, for me it's just that a lot of my world is virtual [now]."

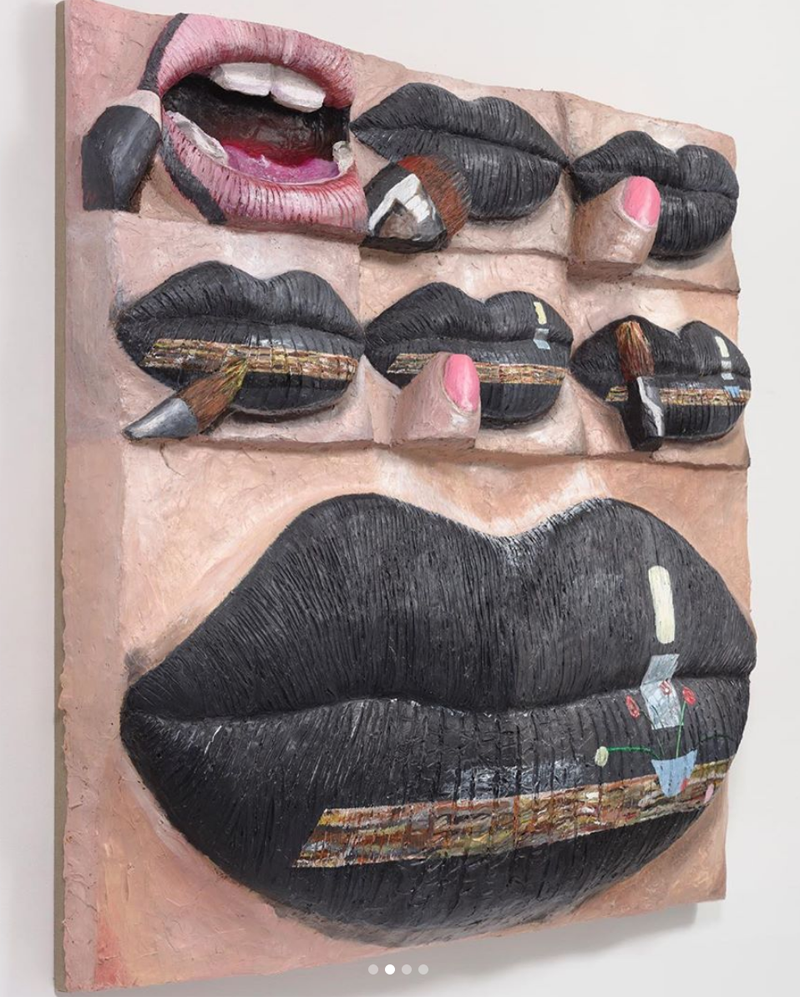

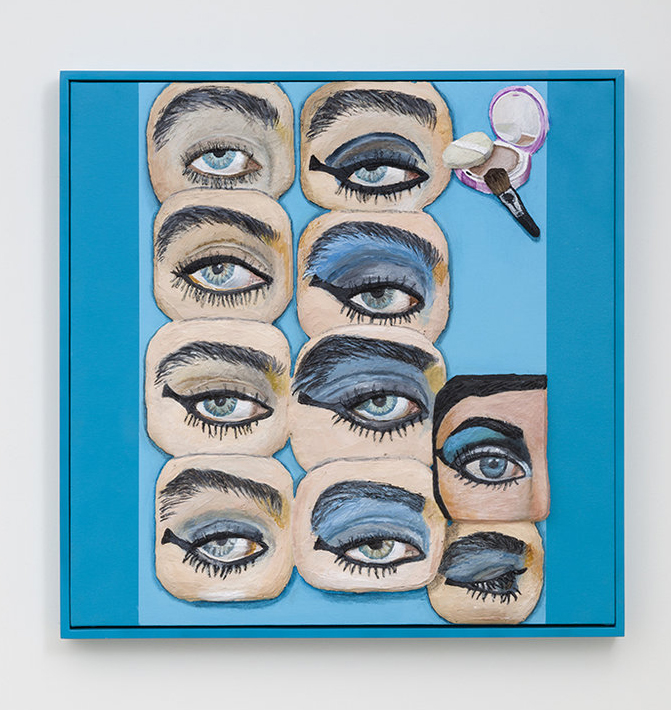

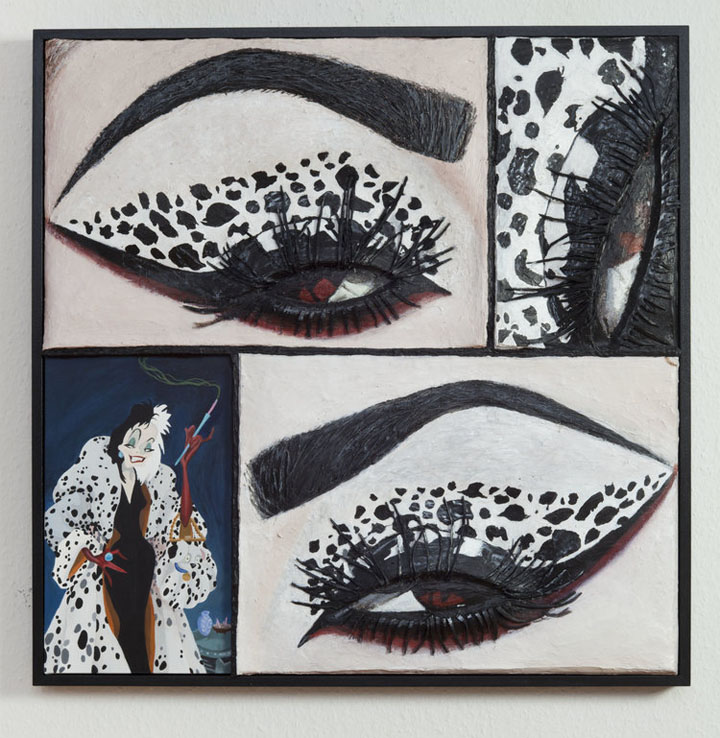

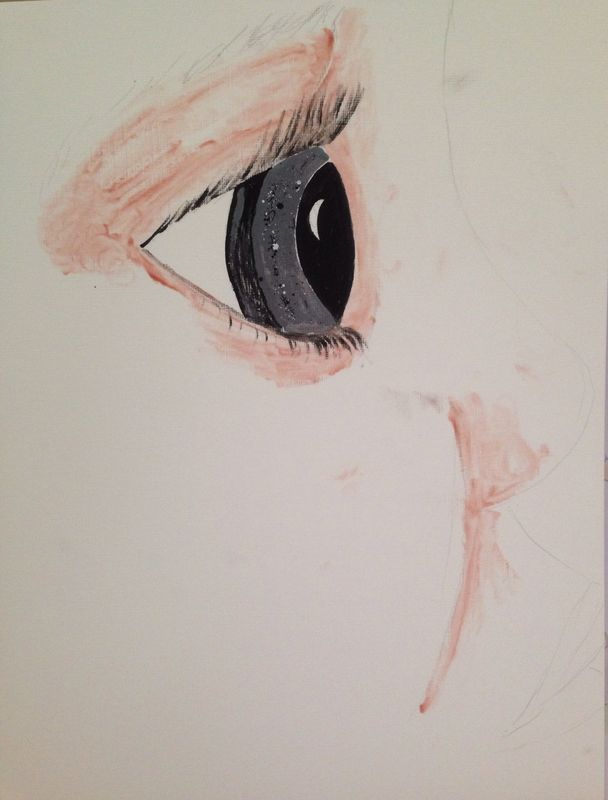

But why makeup, and specifically, makeup tutorials? There seem to be two main themes running through the artist's focus on these online instructions, the first being the relationship between painting and makeup. Beavers explains: "When I started with these paintings I was really thinking that this painting is looking at you while it is painting itself. It’s drawing and painting: it has pencils, it has brushes, and it’s trying to make itself appealing to the viewer. It’s about that parallel between a painting and what you expect from it as well as desire and attraction. It’s also interesting because the terms that makeup artists use on social media are painting terms. The way they talk about brushes or pigments sounds like painters talking shop." Makeup application as traditional painting is a theme that goes back centuries, but Beavers's work represents a fresh take on it. As Ellen Blumenstein wrote in an essay for Wall Street International: "Elements such as brushes, lipsticks or fingers, which are intended to reassure the viewers of the videos of the imitability of the make-up procedures, here allude to the active role of the painting – which does not just stare or make eyes at the viewer, but rather seems to paint itself with the accessories depicted – literally building a bridge extending out from the image…Beavers divests [the image] of its natural quality and uses painting as an analytical tool. The viewer is no longer looking at photographic tableaus composed of freeze-frames taken from make-up tutorials, but rather paintings about make-up tutorials, which present the aesthetic and formal parameters of this particular class of images, which exist exclusively on the net." The conflation of makeup and painting can also be perceived as a rumination on authorship and original sources. Beavers is remaking tutorials, but the tutorials themselves originated with individual bloggers and YouTubers. And given the viral, democratic nature of the Internet, it's nearly impossible to tell who did a particular tutorial first and whether tutorials covering the same material – say, lip art depicting Van Gogh's "Starry Night" – are direct copies of one artist's work or merely the phenomenon of many people having the same idea and sharing it online. Sometimes the online audience cannot distinguish between authentic content and advertising; Beavers's "Burger Eye" (2015), for example, is actually not recreated from a tutorial at all but an Instagram ad for Burger King (and the makeup artist who was hired to create it remains, as far as I know, uncredited).

Another theme is fashioning one's self through makeup, and how that self is projected online in multiple ways. Beavers explains: "I am interested in the ways existing online is performative, and the tremendous lengths people go to in constructing their online selves. Meme-makers, face-painters, people who make their hair into sculptures, are really a frontier of a new creative world…It’s interesting, as make-up has gotten bigger and bigger, I’ve realized what an important role it plays in helping people construct a self, particularly in trans and drag communities. I don’t normally wear a lot of make-up myself, but I like the idea of the process of applying make-up standing in for the process of self-determination, the idea of ‘making yourself’."

As for the artist's process, it's a laborious one. Beavers regularly combs Instagram, YouTube and other online sources and saves thousands of images on her phone. She then narrows down to a few based on both composition and the story they're trying to tell. "I'm arrested by images that have interesting formal qualities, color, composition but also a compelling narrative. I really like when an image is saying something that leaves me unsure of how it will translate to painting, like whether the meaning will change in the context of the history of painting," she says. "I always felt drawn to photos that had an interesting composition, whether for its color or depth or organization. But in order for me to want to paint it, it also had to have interesting content, like the image was communicating some reality beyond its composition that I related to in my life or that I thought spoke in some interesting way about culture." The act of painting for Beavers is physically demanding as well: she needs to start several series at the same time and go back and forth between paintings to allow the layers to dry. They have to lay flat to dry so she often ends up painting on the floor, and her recent switch to an even heavier acrylic caused a bout of carpal tunnel syndrome.

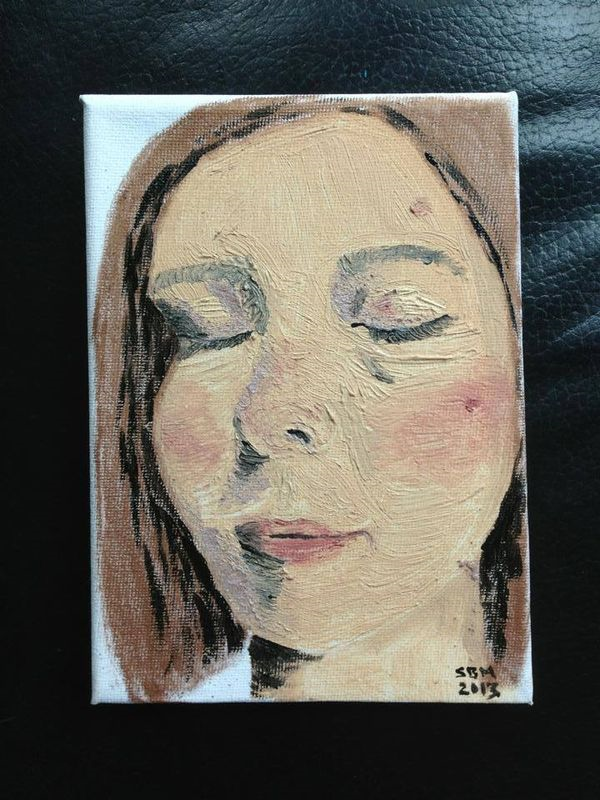

But it's precisely the thick quality of the paint that return some of the tactile nature of makeup application. This is not accidental; Beavers intentionally uses this technique as way to remind us of makeup's various textures and to ensure her paintings resemble paintings rather than a photorealistic recreation of the digital screen. "The depth of certain elements in the background of images has taught me a lot about seeing. I think I have learned that I enjoy setting up problems to solve, that it isn't enough for me to simply render a photo realistically, that I have to build up the acrylic deeply in order to interfere with the rendering of something too realistically," she explains. Sharon Mizota, writing for the LA Times, says it best: "Skin, lashes and lips are textured with rough, caked-on brushstrokes that mimic and exaggerate wrinkles and gloppy mascara. This treatment gives the subjects back some of the clunky physicality that the camera and the digital screen strip away. Beavers’ paintings, in some measure, undo the gloss of the photographic image."

Beavers also uses foam to further build up certain sections so that they bulge out towards the viewer, representing the desire to connect to others online. "Much of what people do online is to try to create connection, to reach out and meet people or talk to people. That is what the surfaces of my painting do in a really literal way, they are reaching off the linen into the viewer’s space," she says. This sculptural quality also points to the reality of the online world – it's not quite "real life" but it's not imaginary either, occupying a space in between. Beavers expands on her painting style representing the online space: "It’s interesting because flatness often comes up with screens, and I think historically the screen might have been read like that, reflecting a more passive relationship. That has changed with the advent of engagement and social media. What’s behind our screen is a whole living, breathing world, one that gives as much as it takes. I mean it is certainly as 'real' as anything else. I see the dimension as a way to reflect that world and the ways that world is reaching out to make a connection. Another aspect is that once these works are finished, they end up circulating back in the same online world and now have this heightened dimensionality – they cast their own shadow. They’re not a real person, or burger, or whatever, but they’re not a photo of it either, they’re something in between."

Let's dig a little more into what all this means in terms of makeup, the beauty industry and social media. Beavers' work can be viewed as a simultaneous critique and celebration of all three. Sharon Mizota again: "[The tutorial paintings] also pointedly mimic the act of putting on makeup, reminding us that it is something like sedimentation, built up layer by layer. There is no effortless glamour here, only sticky accretion. That quality itself feels like an indictment — of the beauty industry, of restrictive gender roles. But an element of playfulness and admiration lives in Beavers’ work. They speak of makeup as a site of creativity and self-transformation, and Instagram and other social media sites as democratizing forces in the spread of culture. To be sure, social media may be the spur for increasingly outré acts, which are often a form of bragging, but why shouldn’t a hamburger eye be as popular as a smoky eye? In translating these photographs into something more physical, Beavers asks us to consider these questions and exposes the duality of the makeup industry: The same business that strives to make us insecure also enables us to reinvent ourselves, not just in the image of the beautiful as it’s already defined, but in images of our own devising."

This ambiguity is particularly apparent in Beavers's 2015 exhibition, entitled Ambitchous, which incorporated beauty Instagrammers and YouTubers' makeup renditions of Disney villains alongside "good" characters. Blumenstein explains: "So it isn’t protagonists with positive connotations which are favoured by the artist, but unmistakably ambivalent characters who could undoubtedly lay claim to the neologism ambitchous, which is the name given to the exhibition. Like the original image material, this portmanteau of ‘ambitious’ and ‘bitchy’ is taken from social media and its creative vernacular, and is used, depending on the context, either in a derogatory fashion – for example for women who will do absolutely anything to get what they want – or positively re-interpreted as an expression of female self-affirmation. Beavers also applies this playful and strategic complication of seemingly unambiguous contexts of meaning to the statements contained in her paintings. It remains utterly impossible to determine whether they are critically exaggerating the conformist and consumerist beauty ideals of neo-capitalism, or ascribing emancipatory potential to the conscious and confident use of make-up."

More recently, Beavers has been using her own face as a canvas and making her own photos of them her source material, furthering her exploration of the self. "Staring at yourself or your lips for hours is pretty jarring. But I like it, because it creates this whole other level of self,” she says.

This shift also points to another dichotomy in Beavers's work: in recreating famous works of art on her face, she is both critiquing art history's traditional canon and appreciating it, referring to them as a sort of fan art. "I think a lot of the works that I have made that reference art history—like whether it's Van Gogh or whoever it is—have a duality where I really respect the artist and I'm influenced by them, and at the same time I'm making it my own and poking a little fun. And so, a lot of these pieces originated with the idea of fan art. You'll find all sorts of Starry Night images online that people have painted or sculpted or painted on their body. It comes out of that. And I just started to reach a point where I was searching things like 'Franz Kline body art,' and I wasn’t finding that, so I had to make my own. Then it started to get a little bit geekier. I have a piece in the show where I am painting a Lee Bontecou on my cheek, that's a kind of art world geeky thing—you have to really love art to get it."

Ultimately, Beavers perceives the intersection of makeup and social media as a force for good. While the specter of misinformation is always lurking, YouTube tutorials and the like allow anyone with internet access to learn how to do a smoky eye or a flawlessly lined lip. "I think for a lot of people social media is kind of like the weather. We don't have a lot of control of it, it just is. It gives and it takes away. There's no doubt that it has connected people in ways that are great and productive, allowing people to find communities and organize activism, it can also be a huge distraction…I approach looking at images there pretty distantly, more as a neutral documentarian, and I come down on the side of seeing social media as an incredibly useful, democratic tool in a lot of ways," she concludes.

On the other side of social media, Beavers is interested on how content creators help disseminate the idea of makeup as representing something larger and more meaningful than traditional notions of beauty. "I was super fascinated with makeup and all of the kinds of costume makeup and things you can find online that go away from a traditional beauty makeup and go towards something really wild and cool…I also had certain paintings in [a 2016] show that were much more about costume makeup, that were going away from beauty. That’s the thing that gives me hope. When I go through makeup hashtags on Instagram, there will be ten or twenty beauty eye makeup images and then one that’s painted with horror makeup. There are women out there doing completely weird things, right next to alluring ones." In the pandemic age, as people's relationships with makeup are changing, "weird" makeup is actually becoming less strange. Beavers' emphasis on experimental makeup is more timely than ever. I also think she's documenting the gradual way makeup is breaking free of the gender binary. She says: "I mean with makeup, and the whole conversation around femininity and makeup—I think for a long time when I was making makeup images, there were people that just thought, 'Oh, that's not for me,' because it's about makeup, it's feminine. But it’s interesting, the culture is shifting. I just saw the other day that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did a whole Instagram live where she was putting on her makeup and talking about how empowering makeup is for trans communities…some people see make-up as restrictive or frivolous, but drag performers show how it can be liberating and life-saving." Another point to consider in terms of gender is the close-up aspect of Beavers's paintings. With individual features (eyes, lips, nails) separated from the rest of the face and body and removed from their original context, they're neither masculine nor feminine, thereby reiterating that makeup is for any (or no) gender.

(images from Gina Beavers's website and Instagram)

All I can say is, I love these paintings. Stylistically, they're right up my alley – big, colorful and mimicking makeup's tactile nature so much that I have a similar reaction to them as I do when seeing makeup testers in a store: I just want to dip my hands in them and smear them everywhere! I also enjoy the multiple themes and levels in her work. Beavers isn't commenting just on makeup in the digital age, but also self-representation online, shifting attitudes towards makeup's meaning, the relationship between painting and makeup, and Western art history.

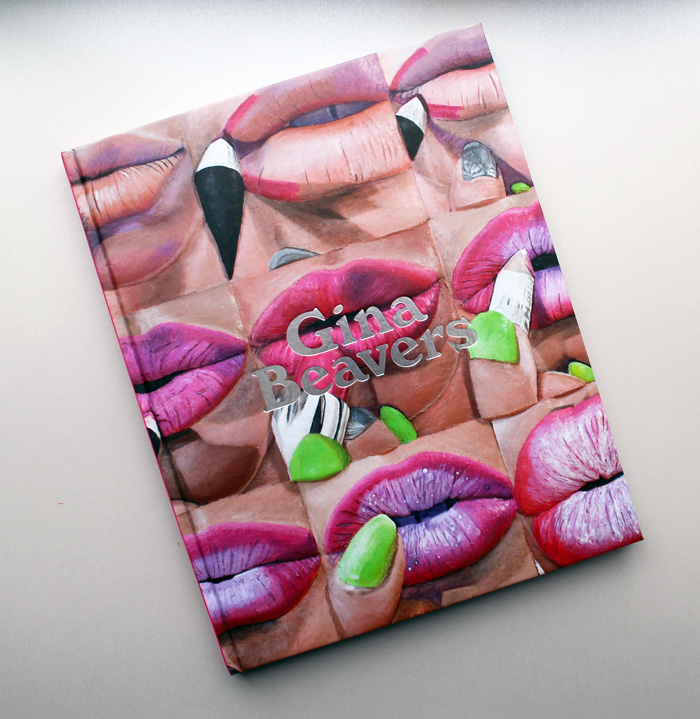

What do you think of Beavers's paintings? If you like it I would highly recommend the monograph, which is lovely and fairly affordable at $40.