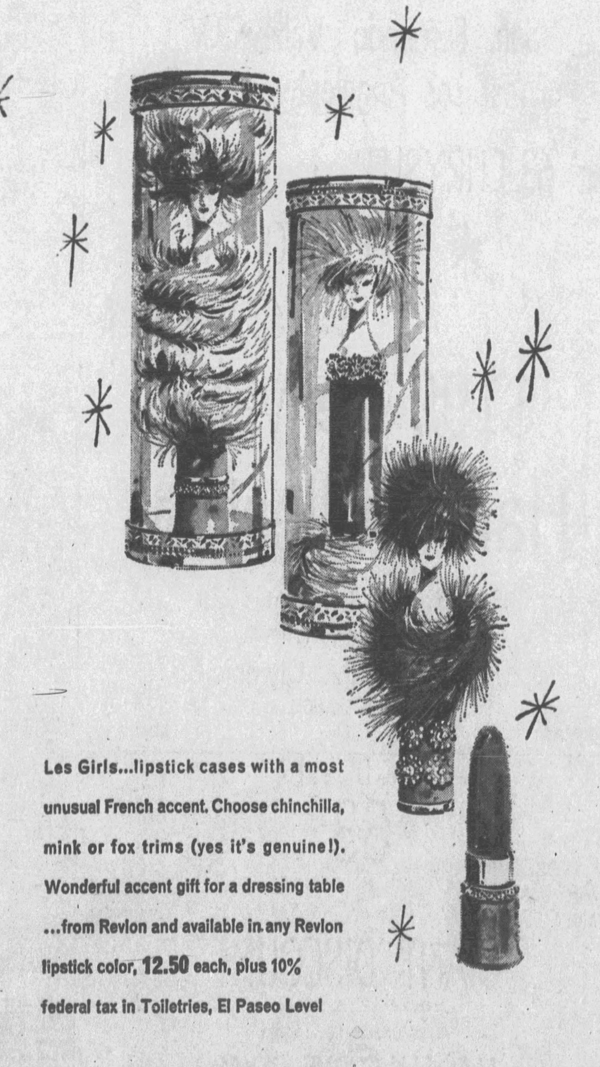

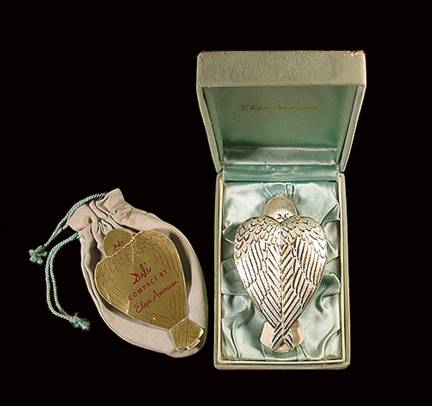

I love when I get an inquiry to which I can actually give a solid response. A gentleman sent in this picture he had of an old lipstick and asked if I could identify it and provide any sense of its monetary value.

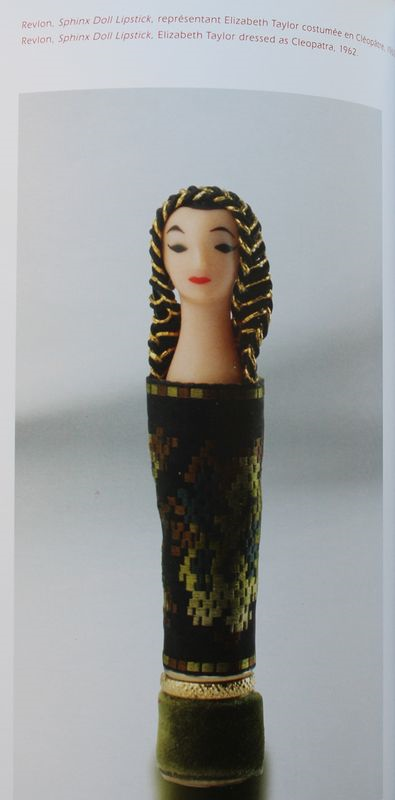

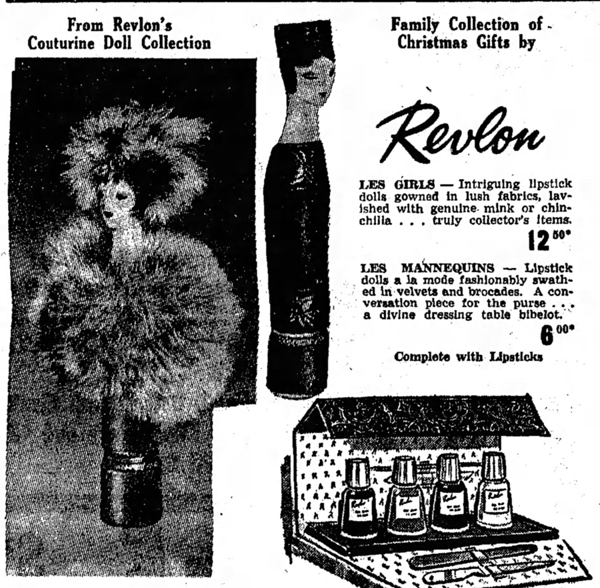

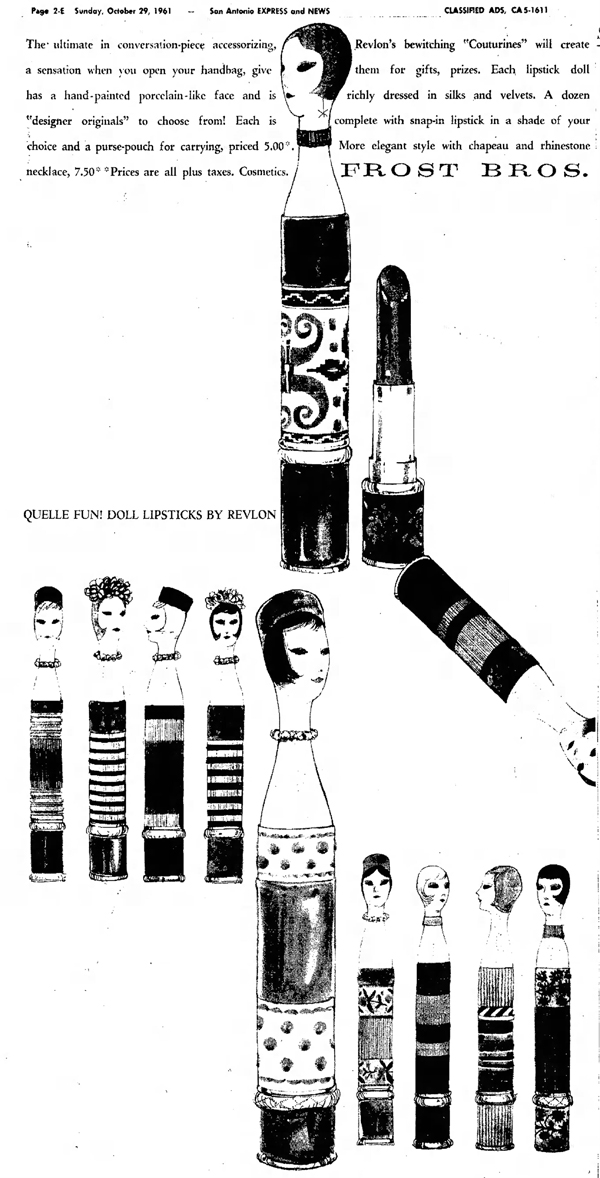

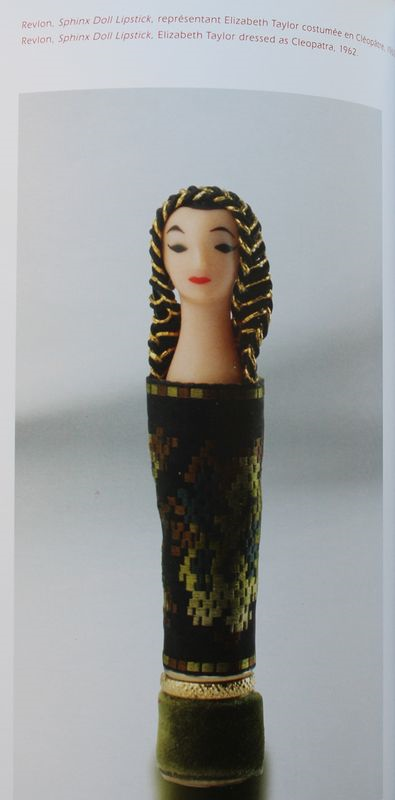

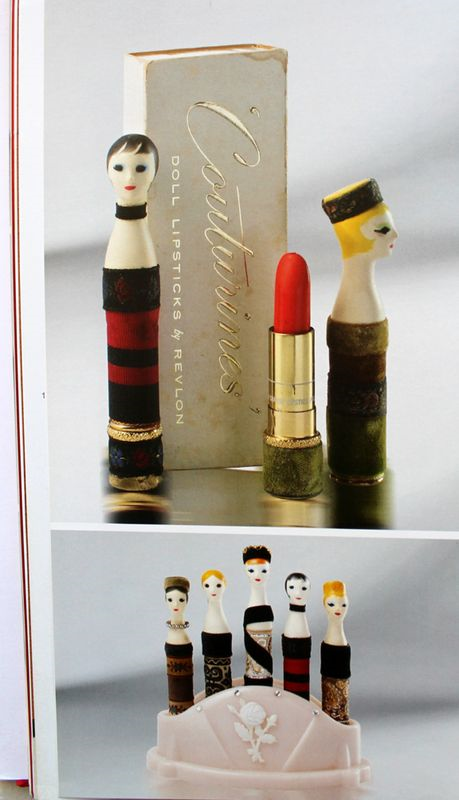

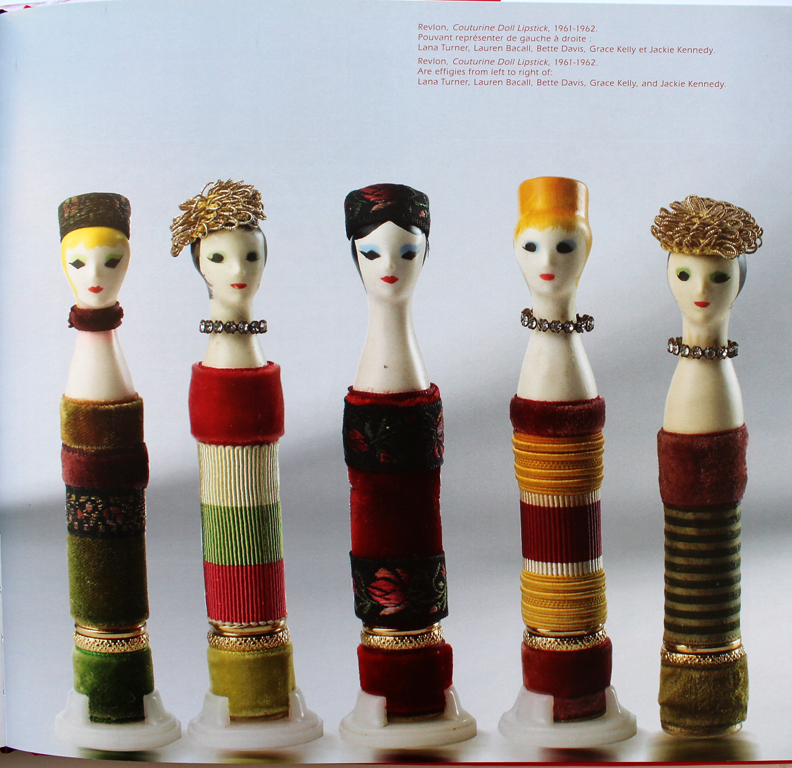

I recognized it immediately as one of the Revlon Couturines doll lipsticks released between 1961 and 1963. But which one? The only one I recognize off the top of my head is Liz Taylor as Cleopatra, since it's pretty obvious.

Fortunately the Revlon Couturines appear in Lips of Luxury (which I highly recommend for any beauty aficionado – check out my review here and in-person pics here.) According to the photos in the book it's not Marilyn Monroe.

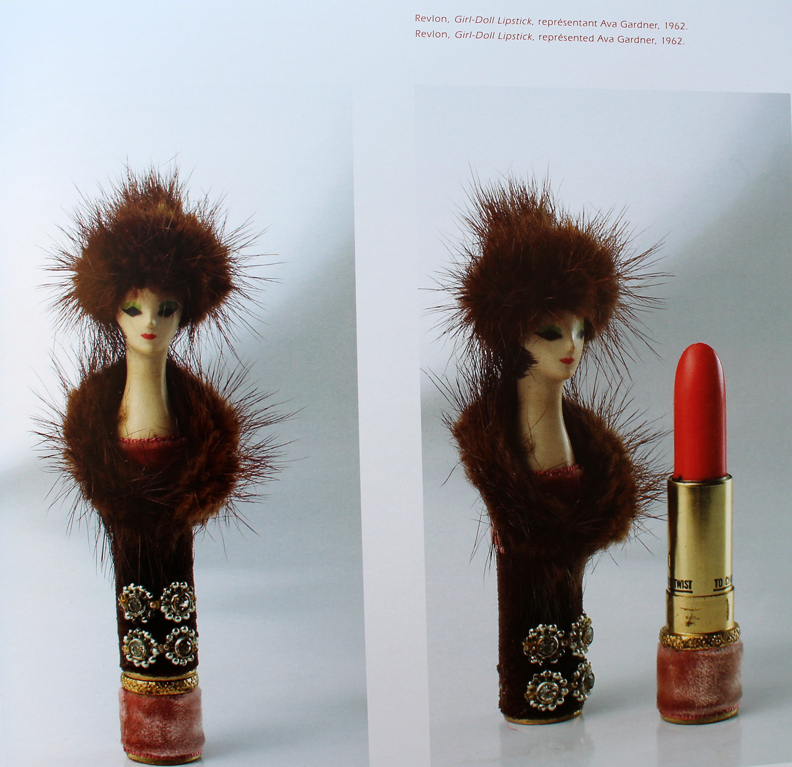

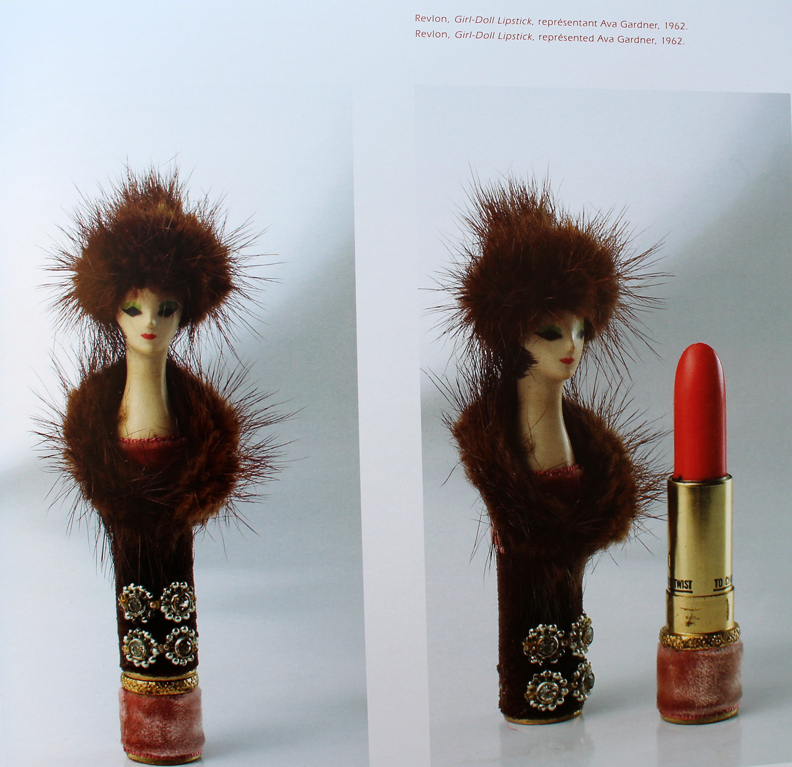

Or Ava Gardner.

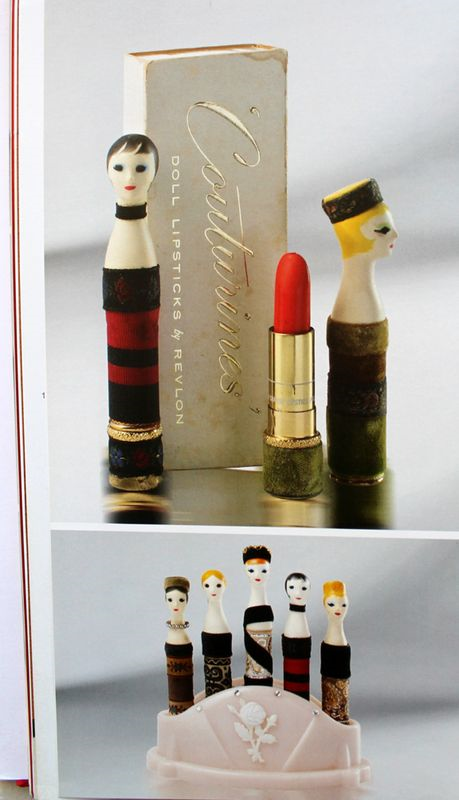

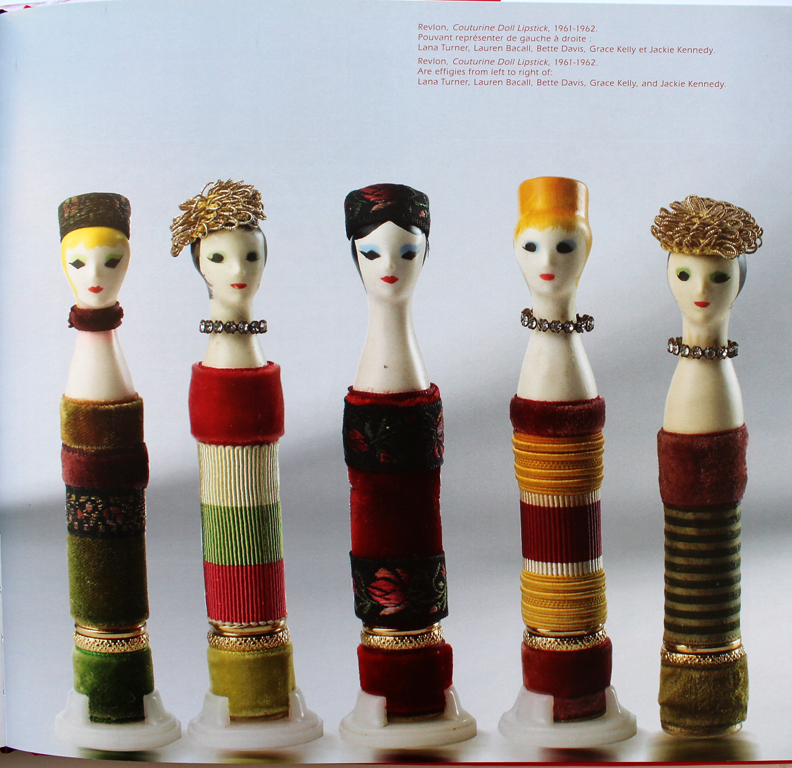

So it must be one of these ladies.

Aha! Looks like it's Jackie Kennedy (last one on the right.)

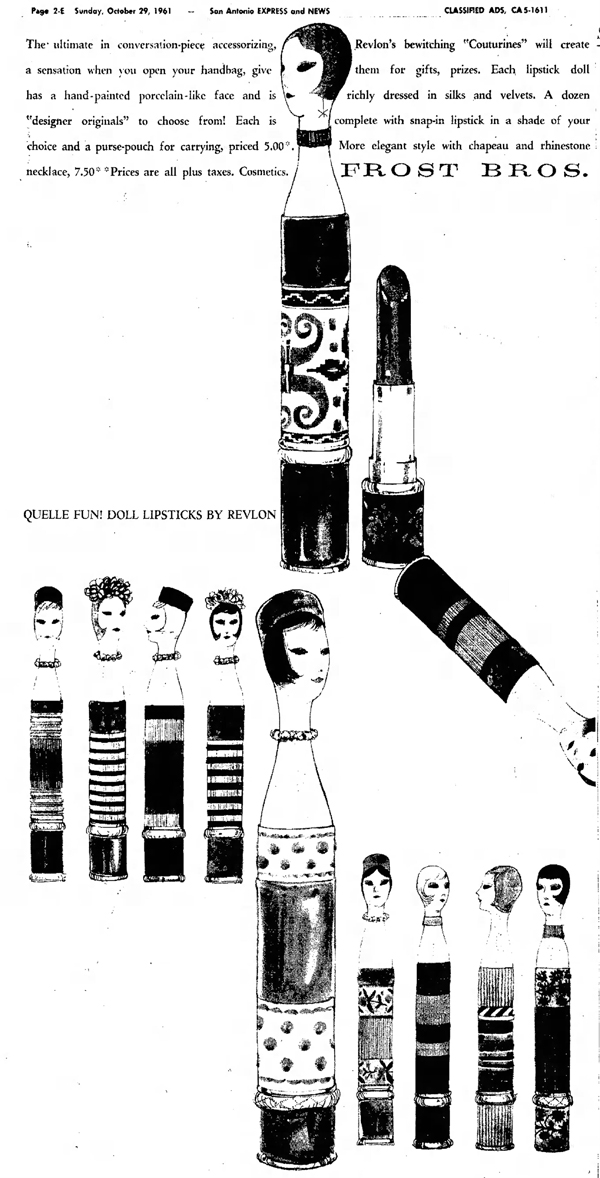

What's fascinating to me about the submitter's photo is that his doll appears to be wearing a little fur stole around her neck, whereas in the photo from the book she doesn't have one. As for the value, Revlon Couturines can fetch a pretty hefty price. Even though the photo is blurry, the one submitted to me looks to be in excellent condition. And given that she has a stole, which I'm assuming is original (the original Marilyn Monroe figurine has neckwear as well, which isn't shown in the picture in Lips of Luxury), that would probably increase the value. I think a fair asking price would be $150-$250. At the moment I don't even see any Jackie figurines for sale.

What do you think of these? This post reminds me that I really need to track down at least one for the Museum – I can't believe I don't own any. Another one (or 8) to add to the old wishlist.

Update, 2/6/2020: It only took 5.5 years, but I finally procured a few of these lovely ladies for the Museum!

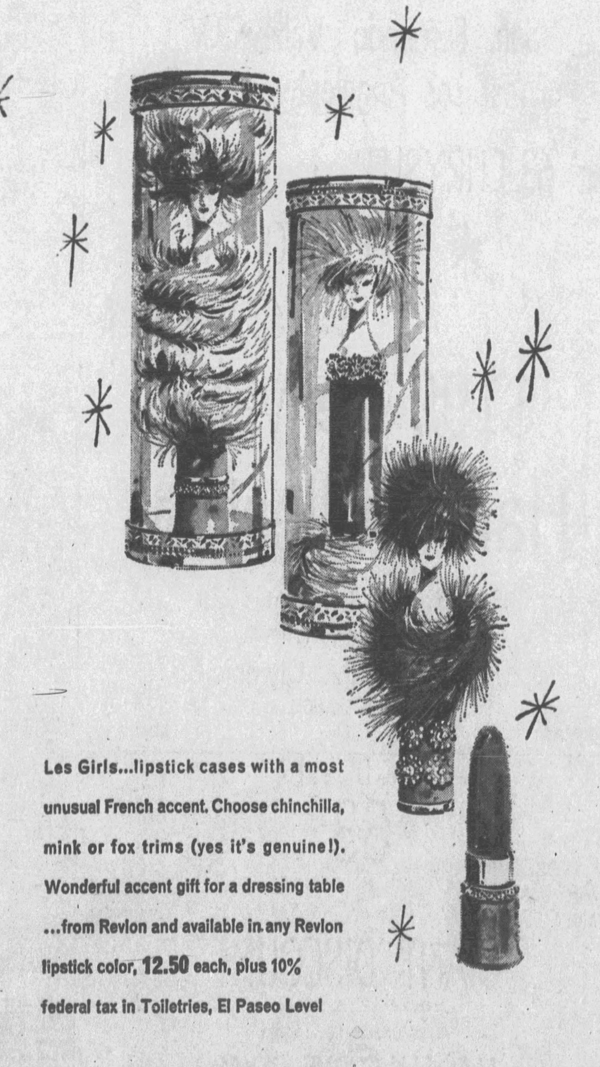

I am sorry to say that I can confirm these are not cruelty-free. As a matter of fact, Revlon made it a point to highlight the "genuine" mink, fox and chinchilla used. How times have changed. I'm also wondering whether all the ones listed for sale over the years as having brown mink are actually fox fur, as indicated in the ad below. Then again, this was the only ad I saw that referenced fox fur, so maybe the brown ones are mink as well.

The white mink one is not in the best shape – there's a little bit of wear on the paint on her lips and discoloration around her "waist" – but she does have the original box. I'm suspecting the black mark is remnants of a belt, as shown here. (Apologies for changing the background in these photos but I was shooting across several days and was too lazy to retrieve the paper I had used originally.)

The chinchilla-clad lady, however, is basically new in the box. One hundred percent museum quality!

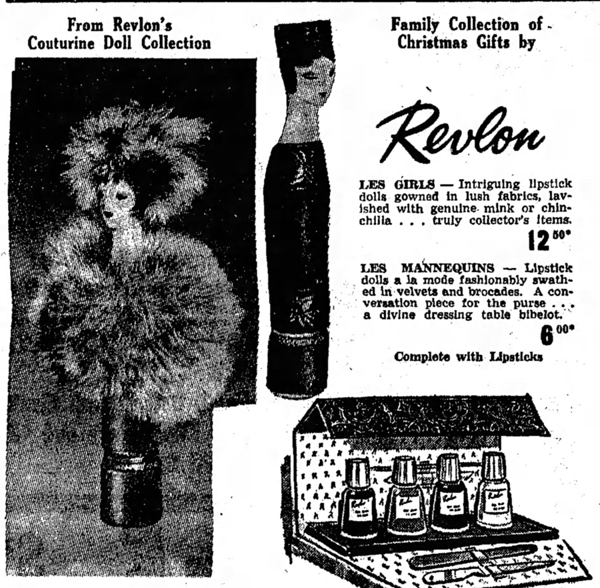

From what I was able to piece together from newspaper ads, the ones without animal fur were advertised as "mannequins" and originally released in 1961, while the chinchilla, fox and mink ones were referred to as "girls" and debuted during the holiday season of 1962. Both series fell under the Couturine name.

There were originally 12 designs, according to this ad. Of course, you paid a little more for the Mannequins with hats and jewelry.

Most of them were similar but had a few details switched up. This is especially true for the Girls series. For example, the brown mink/fox one I procured has the same color velvet at the bottom and one pair of rhinestones, but the one in Lips of Luxury has pink velvet and 4 rhinestones. The colors of the velvet and type of fur were also mixed and matched.

(images from Sun Shine)

But one question remains. I'm wondering where Jean-Marie Martin Hattemberg, whose book Lips of Luxury I referenced earlier, retrieved his information. Obviously I don't think he just made up the idea that each Couturine was intended to be a replica of an actress or other famous woman. But I'm so curious to know how he came to that conclusion since I've never seen them advertised or referred to that way anywhere other than his book. Perhaps he knew someone at Revlon who designed them? Or maybe they were marketed differently outside of the U.S.? In any case, there's no mention of the chinchilla Couturine and several other of the original 12 dolls in Lips of Luxury, so I'm not sure who they're supposed to be. Hopefully one of these days I'll solve another makeup mystery. 😉

Save

I'm so very excited to announce the Makeup Museum's special exhibition in honor of Stila's 25th anniversary! I was too overwhelmed to do a full history of the brand, so I decided to just focus on the famous Stila girl illustrations. If you've been following me for a while you know that the Stila girls were sort of the gateway drug for my interest in collecting makeup and seeing cosmetics packaging as art. For such a milestone anniversary I knew I wanted to pay tribute to them, even though the year is almost over (thankfully – it's been miserable for a number of reasons), especially given that I've been itching to put together a special exhibition for them since at least 2016. I also wanted to try something totally new for the Museum in terms of exhibitions. Technically all of them are online, but instead of putting things on shelves and taking photos, I wanted it to have a more "real" online exhibition feel. I've been doing a lot of thinking the past year or so about how to improve the exhibitions even though I'm so limited in what I can do, and I was really inspired by the Kanebo Compact Museum website, and once the husband showed me Squarespace I was sold. Well that, and the fact that he kindly offered to design the entire exhibition site for me. ;) So I set up a domain there which, if this exhibition is well-received, will serve as the space for the Museum's special exhibitions going forward. The seasonal ones will remain here if I decide to keep going with them. Looking ahead, I think I'd rather focus on more specific topics than general seasonal trends. Not that I can delve too deeply into particular themes given the never-ending lack of resources, but I still want to at least try to do slightly more in-depth exhibitions even though they won't be exactly how I want them. I'm looking at them as a starting point for bigger things.

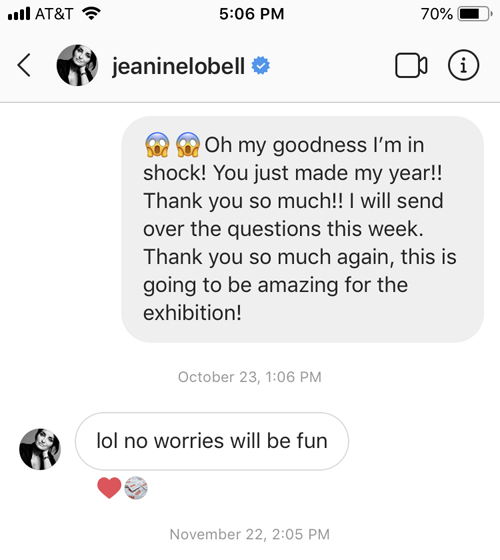

Enough of my blabbing about the basic stuff, I want to give some more details about the exhibition itself. It came together nicely, or at least, it was the one I worked most on with the possible exception of Sweet Tooth (still want to revisit that one!) I really wanted to get interviews with the key people behind the illustrations, so I put my crippling fear of rejection aside and boldly contacted Jeffrey Fulvimari (Stila's original illustrator), Caitlin Dinkins (illustrator during Stila's early aughts heyday) and Naoko Matsunaga (who took over for Dinkins in 2009). While I was disappointed at not hearing back from two of the three, if only one responded, I was glad it was Jeffrey since I've been following him for a while on Instagram and I love his approach to art and his personality. He is quite the character! It ended up giving me so much confidence I reached out to the grand poobah herself and my curatorship namesake, Jeanine Lobell. Yes, I actually DM'ed the founder of Stila on Instagram and asked if she'd be up for an interview. And…and…are you sitting down?? You really need to. Okay, now that you're sitting and won't have far to fall in case you faint, I can tell you that she agreed to do it!!

Not only that, she actually answered all of my interview questions!! You have no idea how ecstatic I was to finally be heard by a major industry figure. Took over a decade but I finally made contact with a big name! So that was most exciting, easily one of the most exciting things to happen in the Museum's 11-year history. And her answers were really good too, I've incorporated them throughout the exhibition so make sure to read through.

As for the items, I didn't take photos of everything in my collection because again, too overwhelming. The Museum has over 130 Stila items, nearly all of which feature the girls. I mean…

The photos I did take have purposely plain backgrounds because I wanted the emphasis to be on the illustrations. I tried to have a good mix of memorabilia and the makeup itself. I even had to iron a few items.

I also included a couple photos of things that I don't actually own but are important in getting a full picture (haha) of the illustrations. I'm pleased with how the sections are arranged, and I must thank my husband for organizing them so perfectly in addition to designing the whole site. I'm thinking of adding a section called Soundbites, a repository of quotes from the both the beauty community and general public telling me why they like the Stila girls or really anything related to the brand, so be sure to email me or comment here. I really wish I could have an app that would "Stila girl-ize" the user, i.e. you upload a picture of yourself and it would automatically generate a Stila girl style illustration of you, just like this. And of course, if the Museum occupied a physical space I'd definitely hire an artist to do live drawings at the exhibition opening – how fun would that be?

So that about wraps it up! Please take a look and tell me what you think of the new exhibition format!

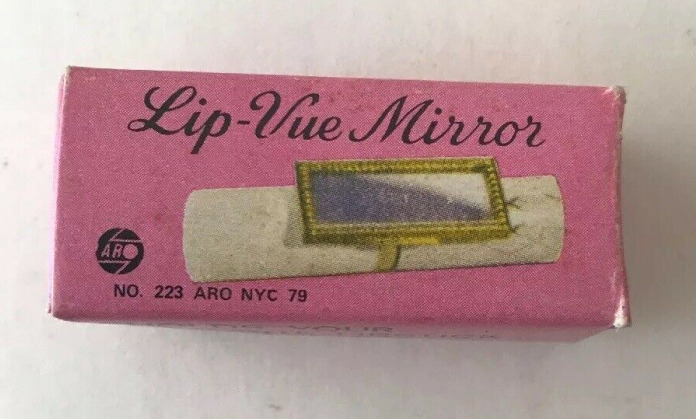

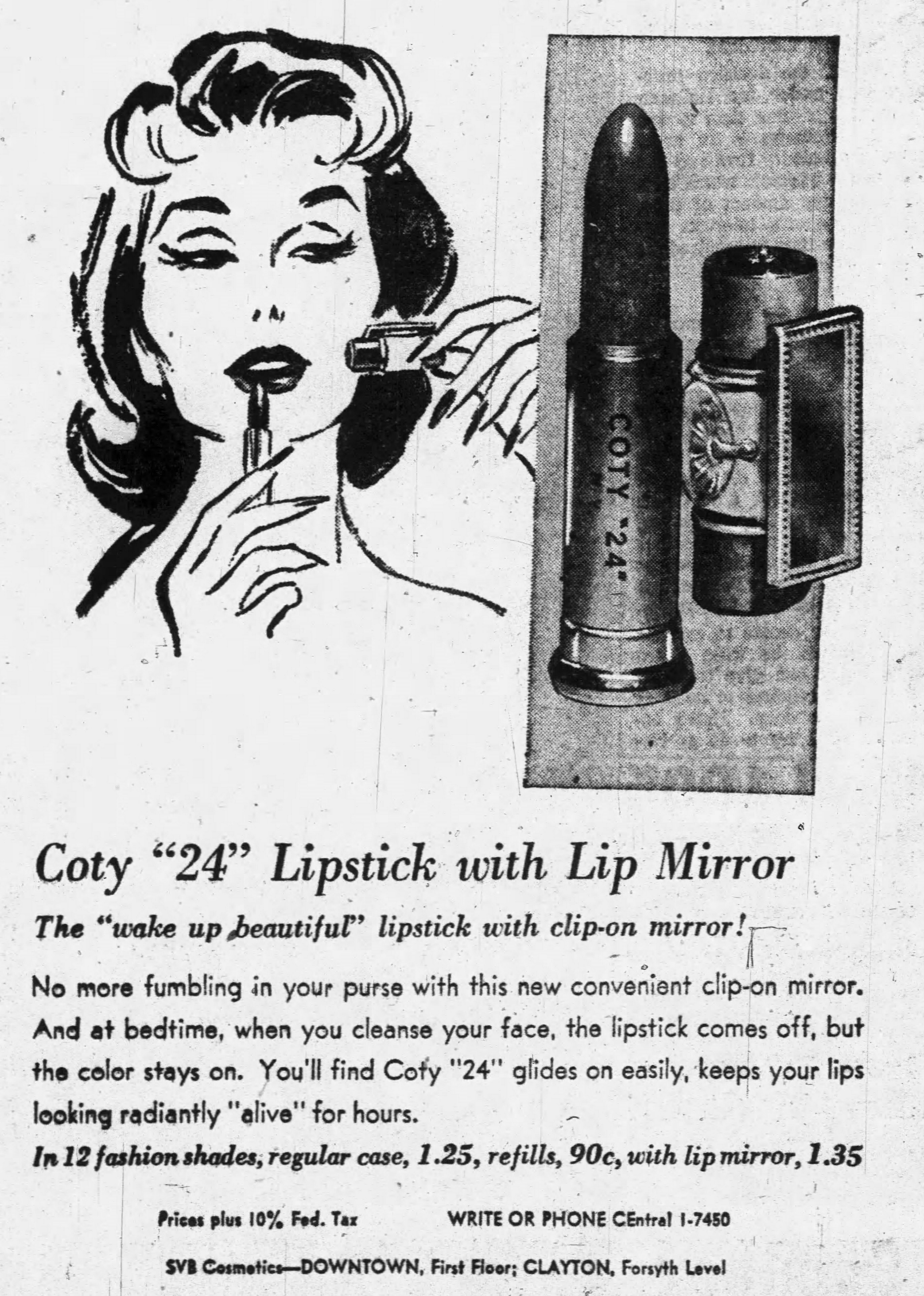

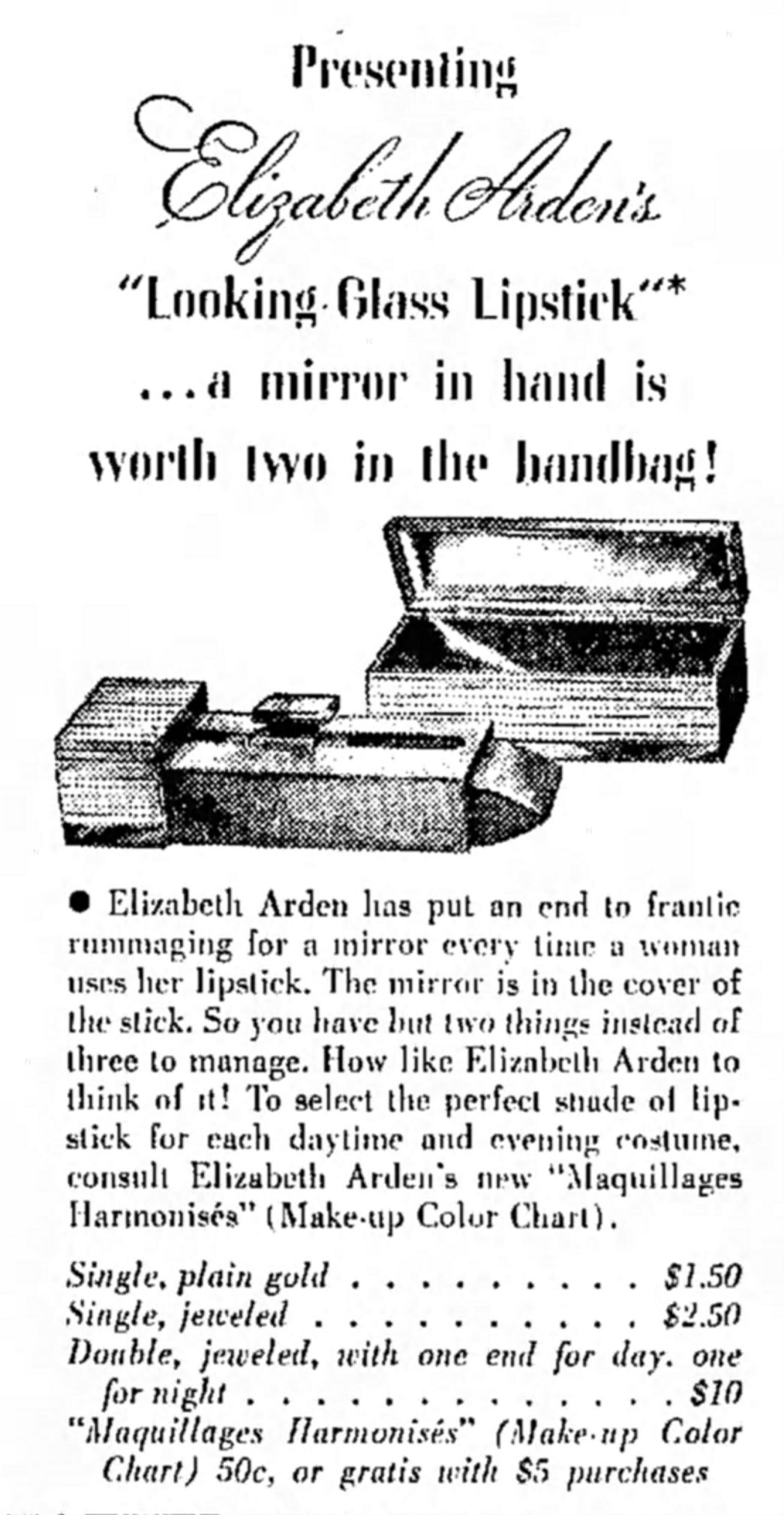

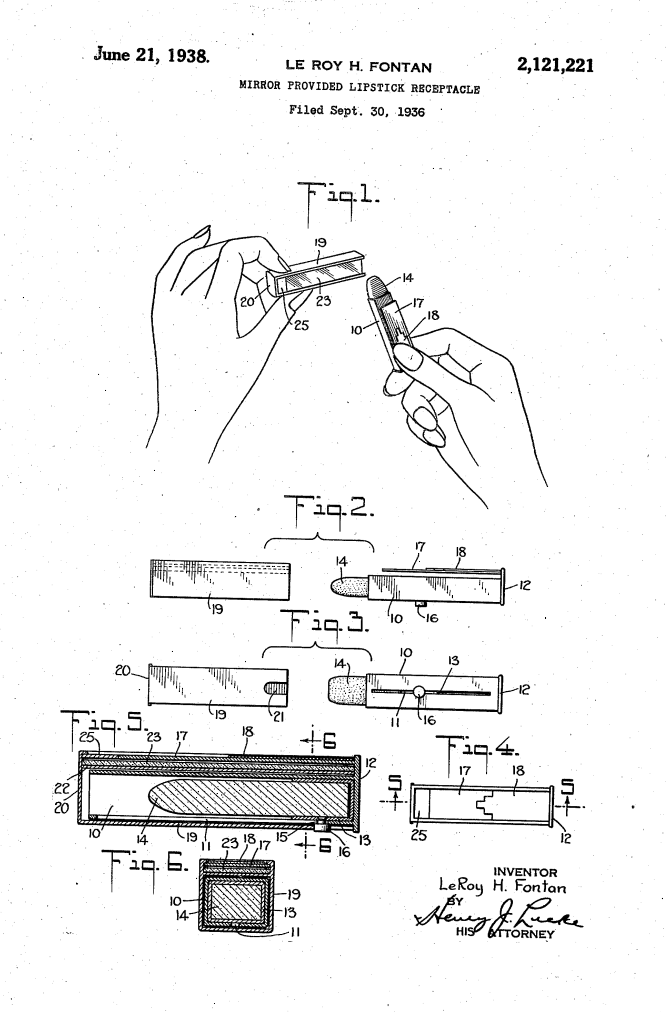

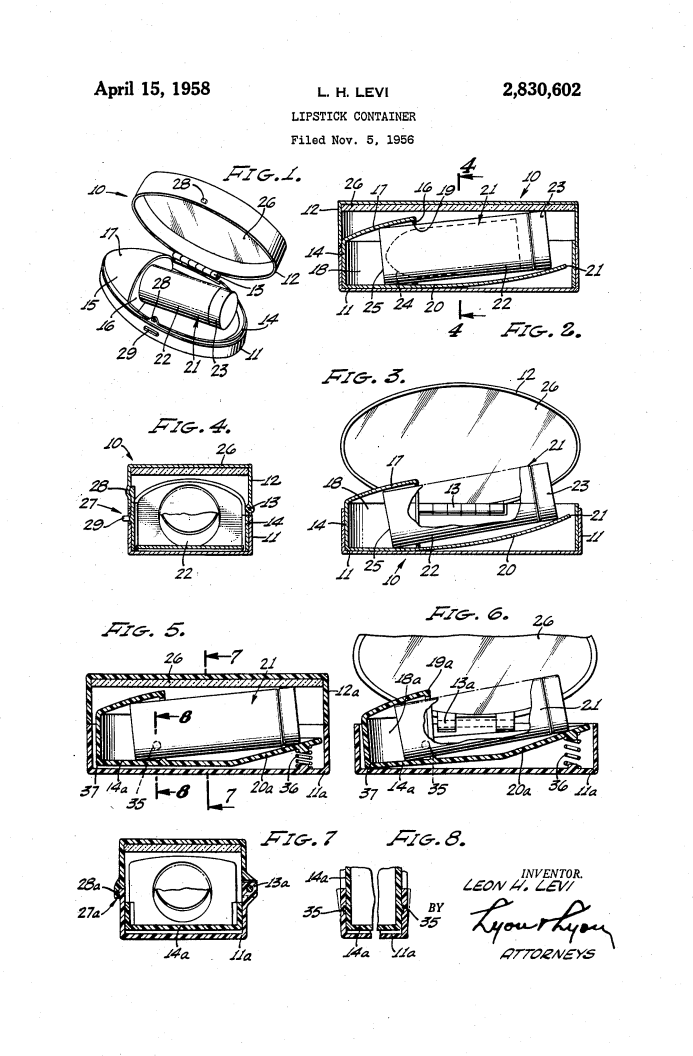

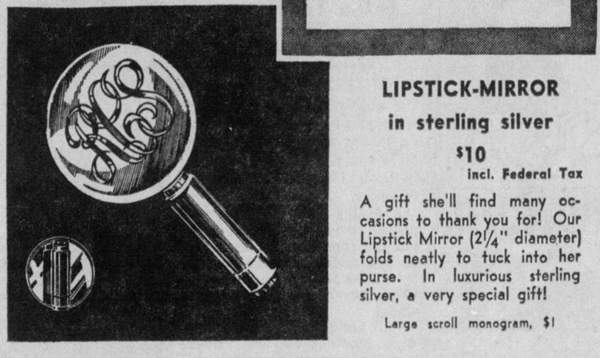

As with lipstick holders and tissues, another piece of makeup ephemera has seem to gone nearly extinct: the built-in lipstick mirror. Sure, there are still some run-of-the-mill fabric and leather lipstick cases with mirrors inside, and some contemporary companies have recycled the basic designs, but no current lipstick mirrors are as novel as their vintage counterparts. Today I’ll take a look (haha) at the various vintage contraptions and mechanisms that allowed for a quick lipstick touch-up. As usual this exploration is not intended to be a comprehensive history of lipstick mirrors, but a brief overview and theories as to why they have mostly disappeared from the beauty milieu as well as the reasons they were even produced in the first place.

The simplest design consisted of a mirrored tube, favored by the likes of Avon and Flame-Glo.

(image from etsy.com)

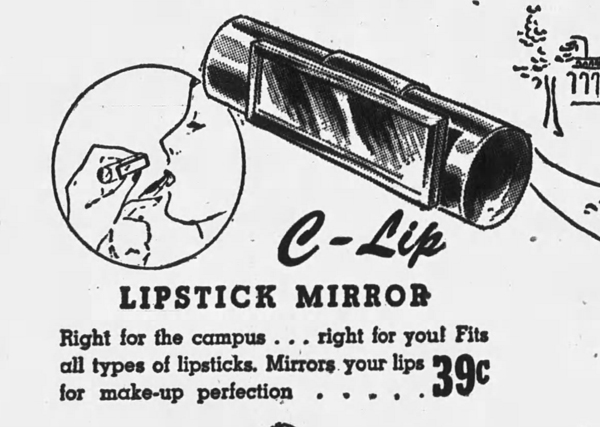

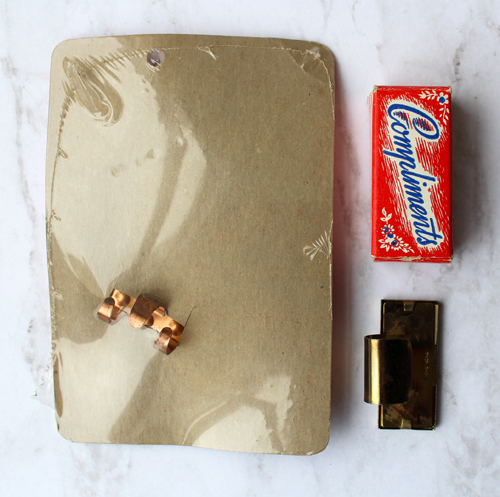

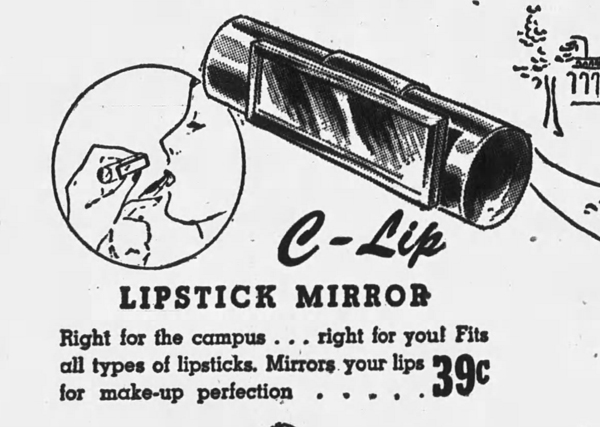

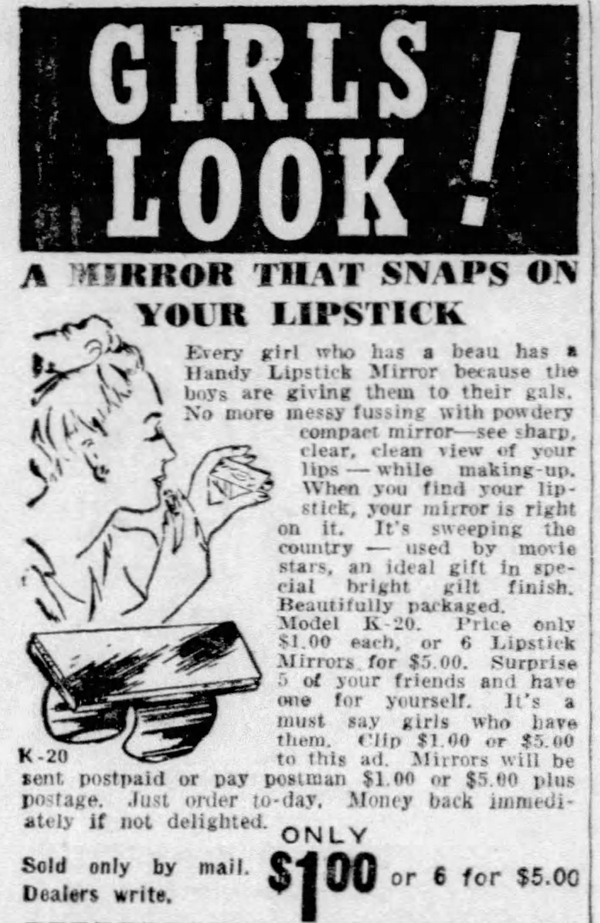

The second most basic and inexpensive option was the humble lipstick clip, which attached directly to the lipstick tube. The adjustable design meant that it could fit virtually any tube and was easily removable.

(image from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

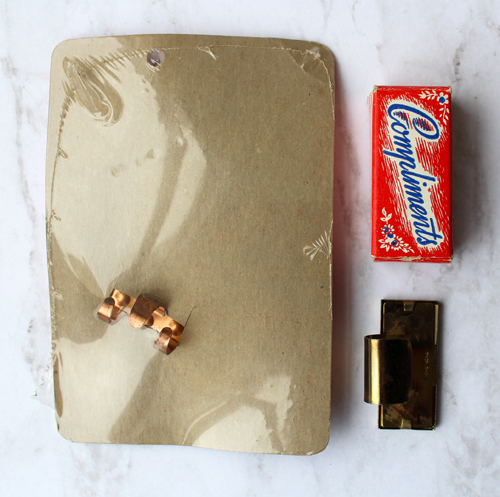

I purchased a couple of these clips for the Museum’s collection. Here we have the “Looky” mirror, which was patented in 1957, and Compliments, which most likely dates to around the same time.

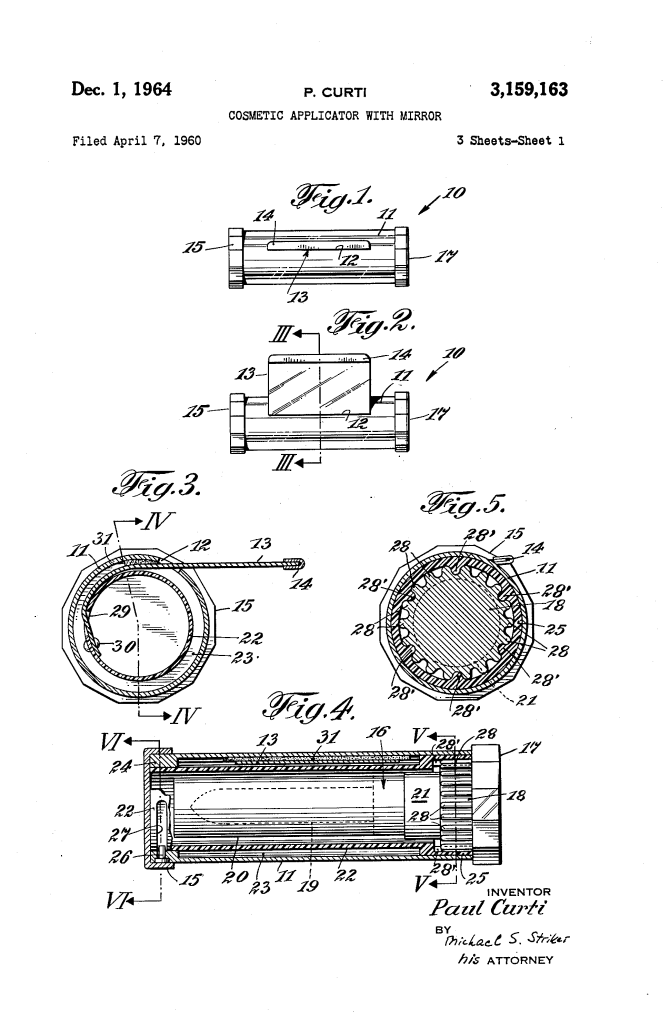

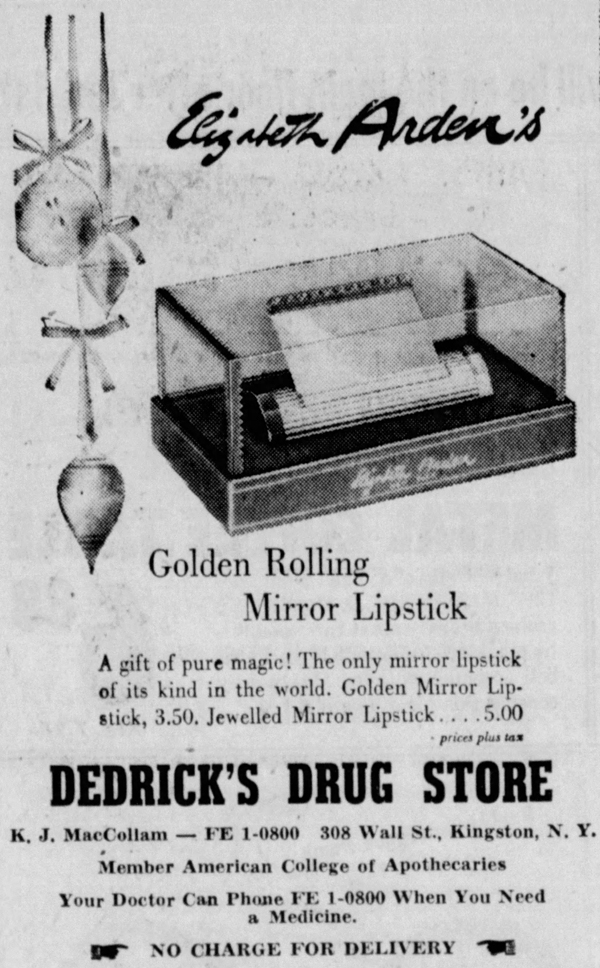

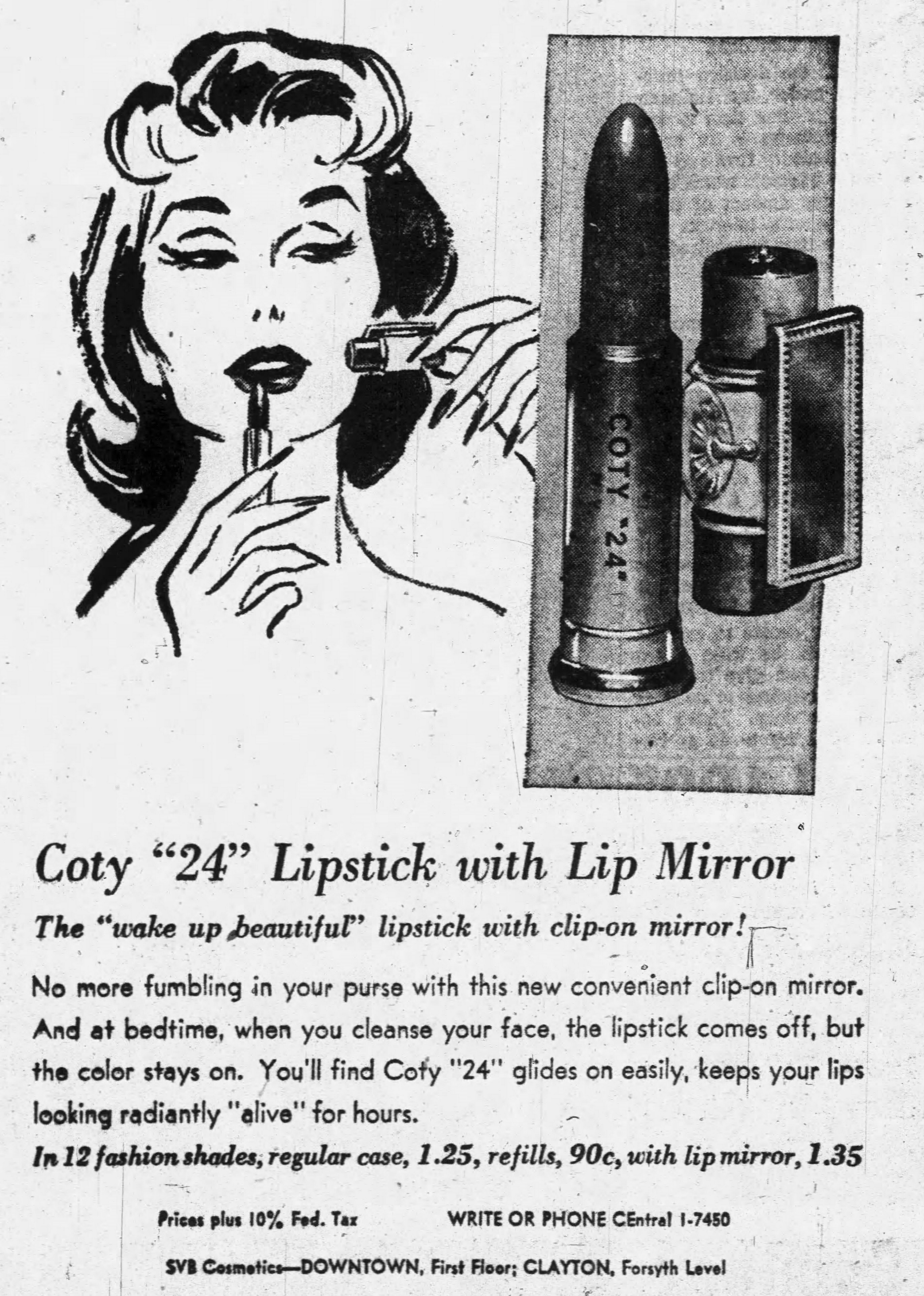

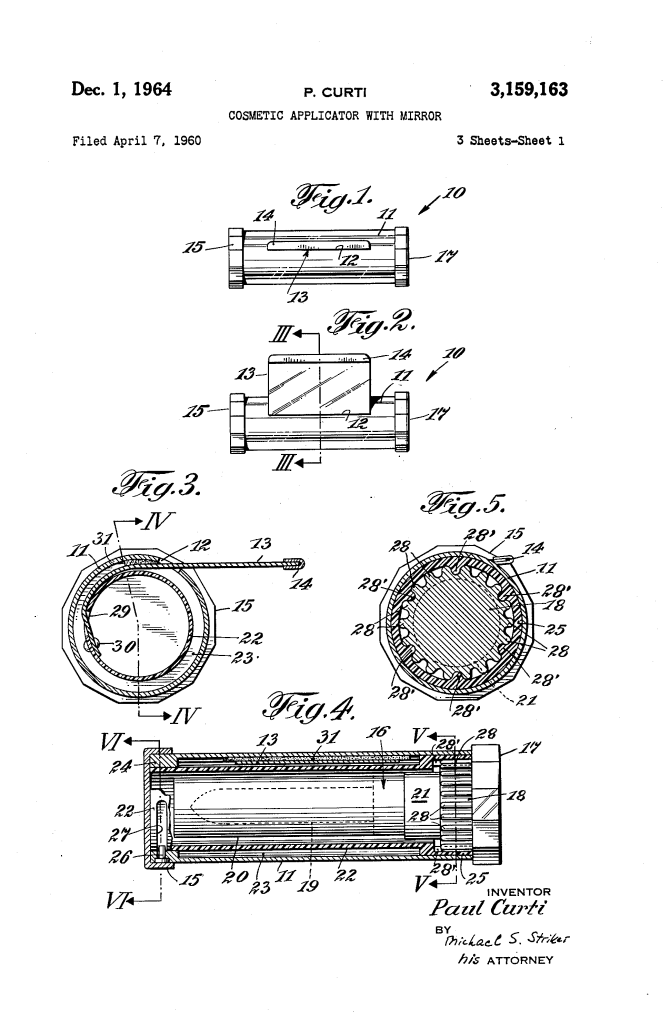

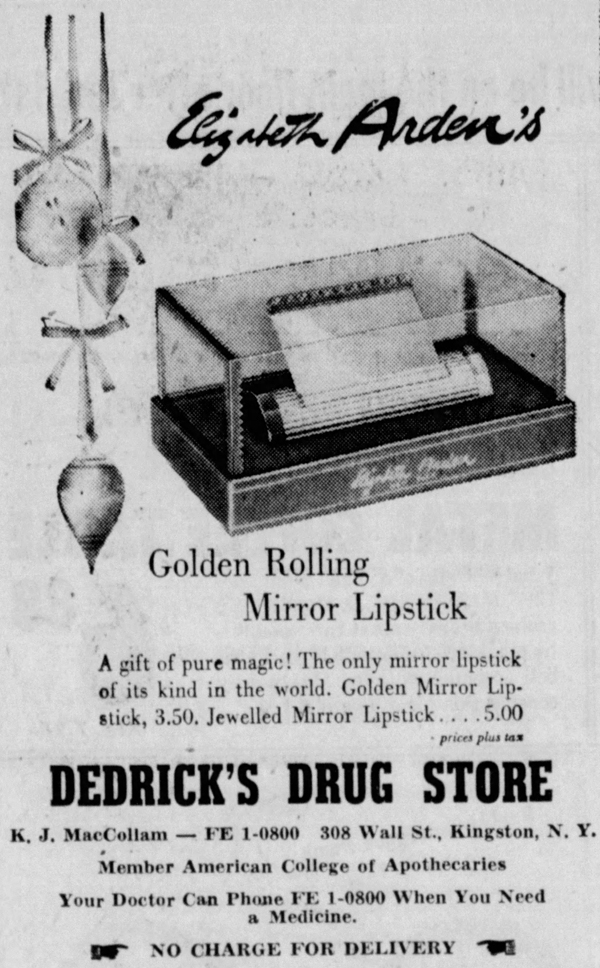

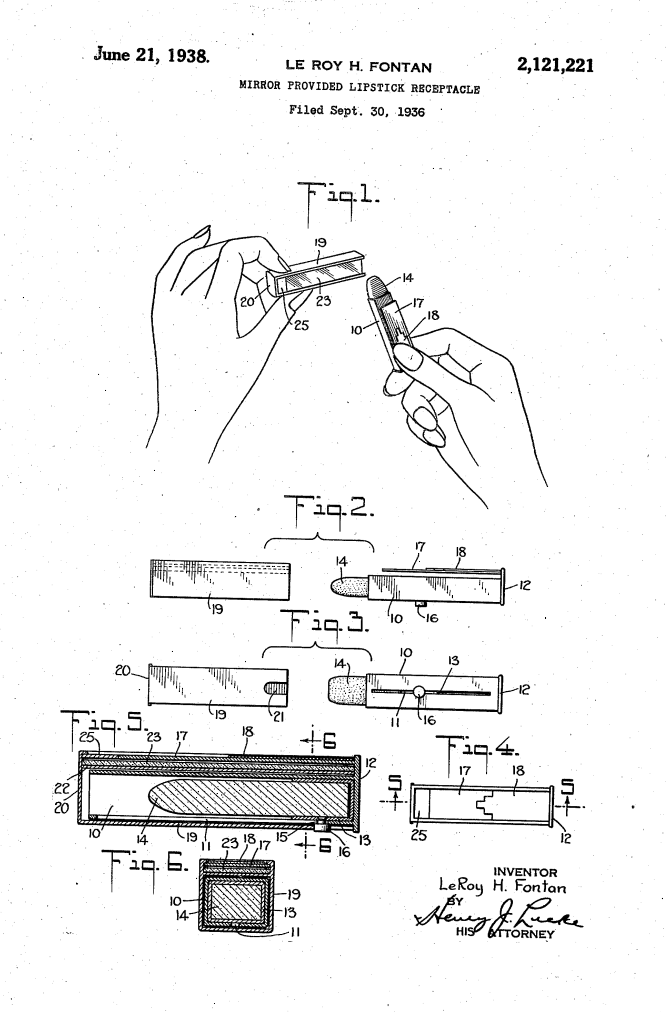

The only design flaw with these types of mirrored tubes and clip-on mirrors was that they would be easily smudged since the mirror was exposed. Enter the folding lipstick mirror and clip! Elizabeth Arden’s Rolling Mirror lipstick debuted in 1959, and while I couldn’t find an exact date for Stratton LipViews, they probably were released around the same time and continued to be sold until the early ’90s.

(images from etsy.com)

Avon also made a far less elegant plastic version.

The mirror could also be protected from smudges and scratches via a sliding mechanism instead of a folding one, as shown in this fan-shaped Stratton lipstick holder.

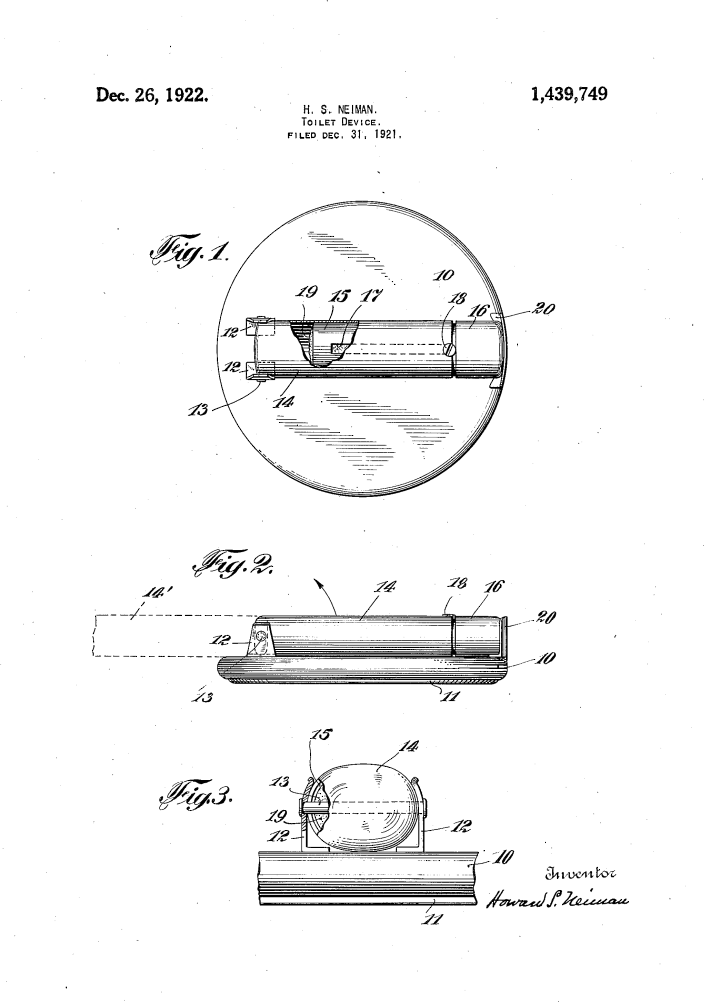

These next few will put a spring in your step. Spring-loaded, sliding cases in which the mirror popped up when the lipstick was opened were also quite popular. Shown here is Volupté’s Lip Look, which dates to 1949-1950. Elgin, Elizabeth Arden and Kotler and Kolpit offered similar cases.

Given how many came up in my search for lipstick mirrors at Ebay and Etsy, it appears that the most widely available model of the spring-loaded variety of lipstick mirrors was a silver carved case accented by gemstones. They’re unmarked, meaning no particular company patented the design and choice of metal. I believe they were mostly sold in department and jewelry stores.

(images from etsy.com)

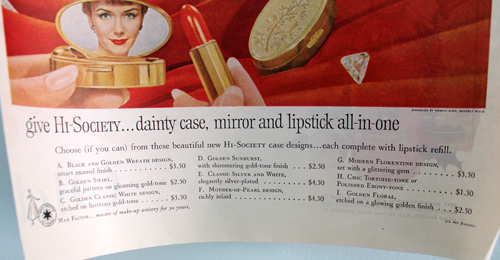

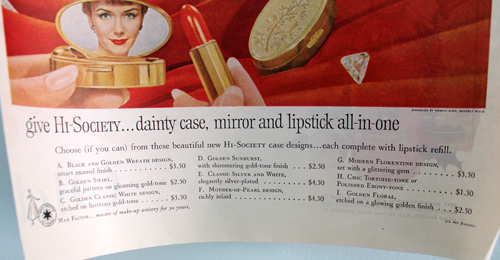

Despite the silver cases’ ubiquity, I’d say the most recognized name-brand spring-loaded lipstick mirror was Max Factor’s Hi-Society, which was heavily advertised from their debut in 1958 through approximately 1965.

You might remember I featured these in the Museum’s holiday 2016 exhibition. I’m still hunting down all the designs, which actually isn’t difficult given how many the company produced.

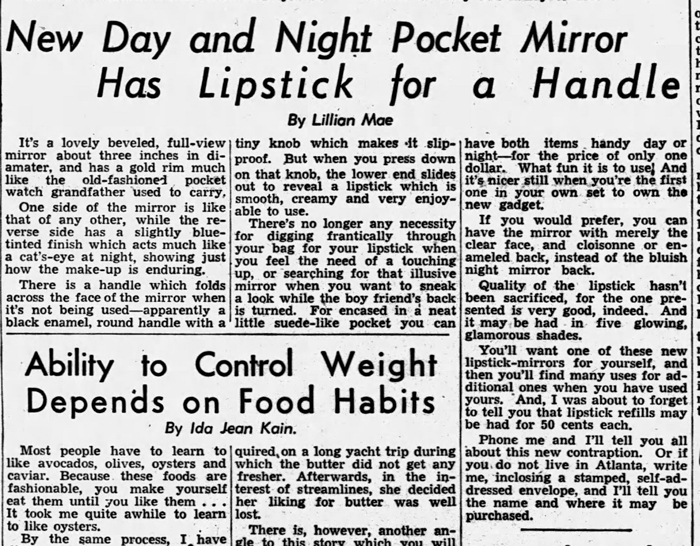

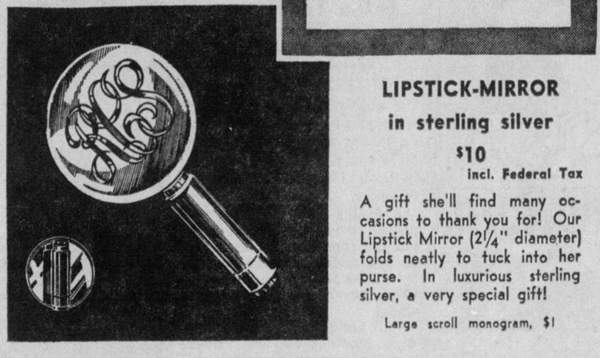

Next up is a more complex version of the folding mirror. Instead of a tube clip, this was an entire folding hand mirror with the lipstick hidden within the handle. Here’s an unmarked, super blingy version. Stratton also made a bunch.

Here are some rather dainty petit point and floral versions by Schildkraut.

(images from ebay.com)

(images from ebay.com)

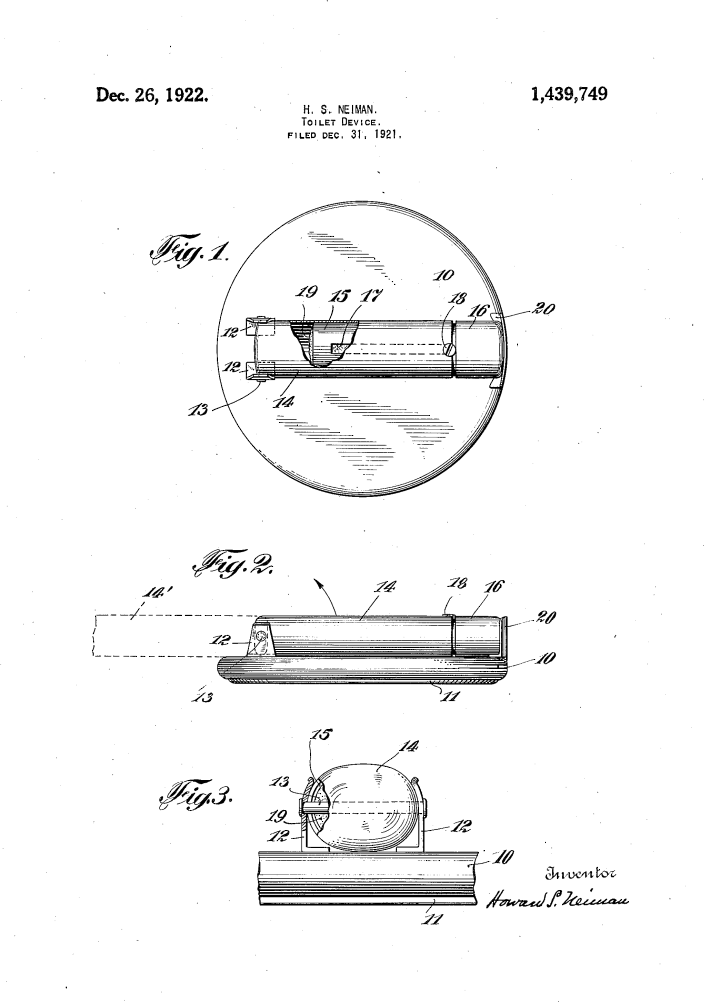

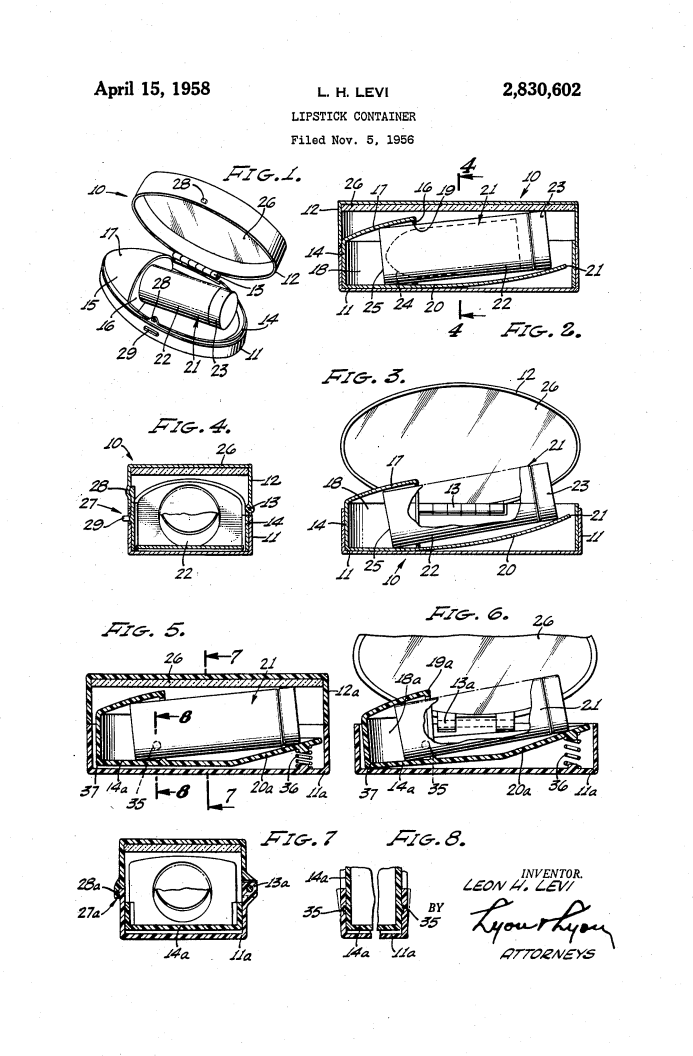

Schildkraut’s represent possibly the earliest form of lipstick mirrors, judging from the patent.

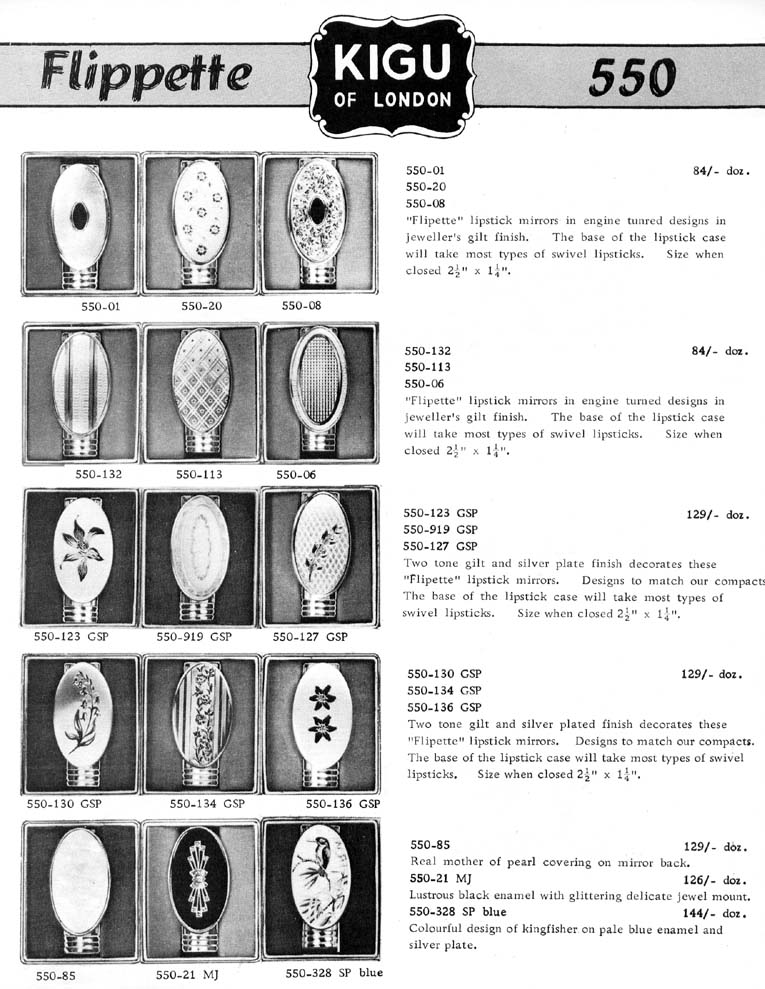

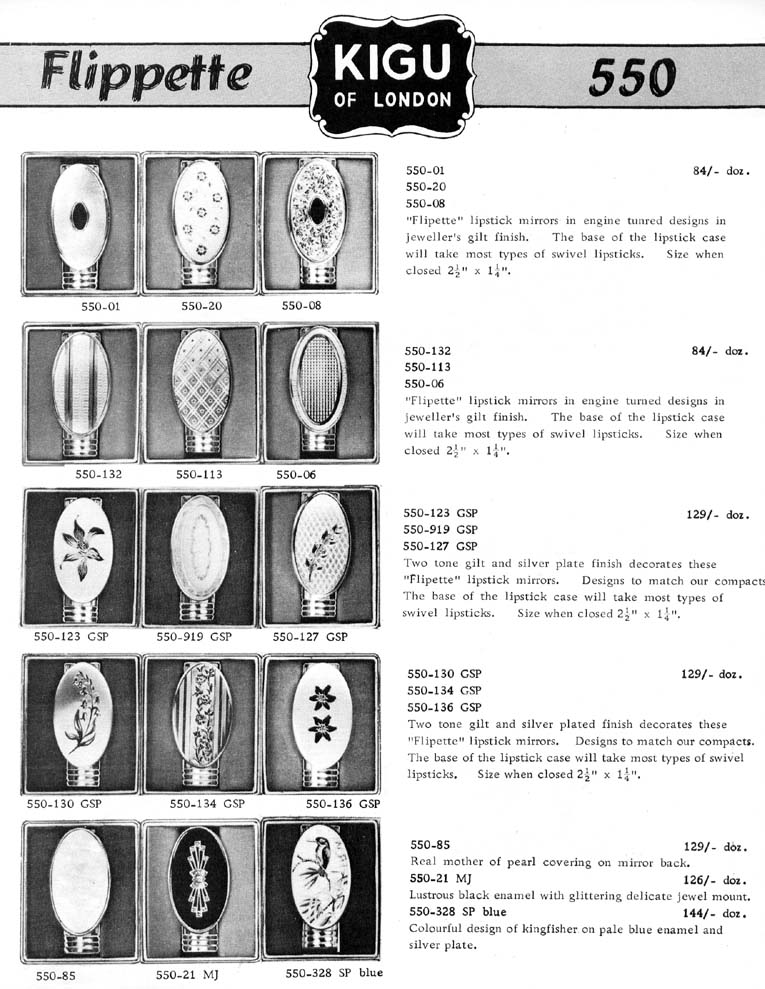

The folding model’s popularity continued well into the 1960s, as evidenced by Kigu’s “Flipette”.

(images from etsy.com)

(image from vintage-compacts.com)

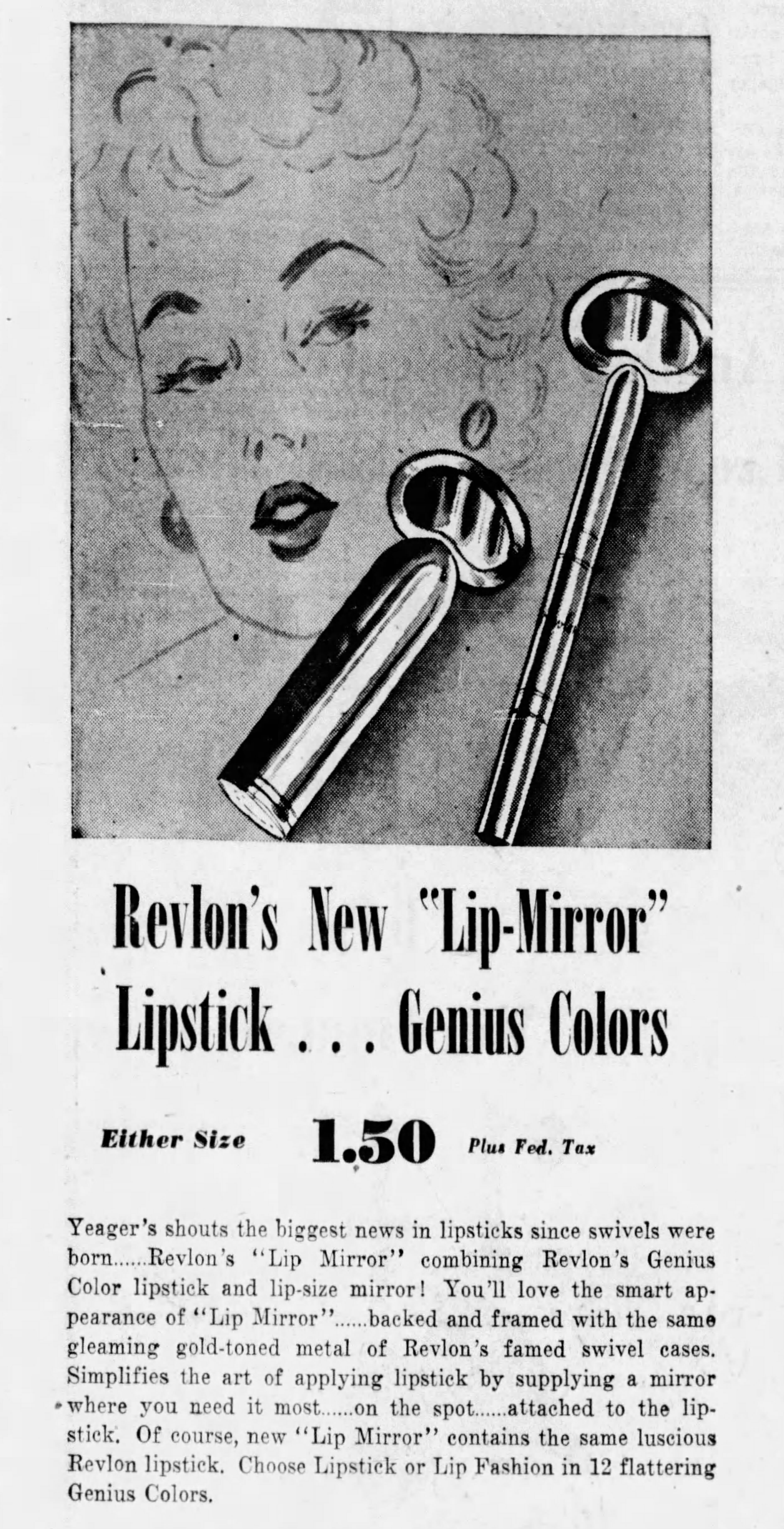

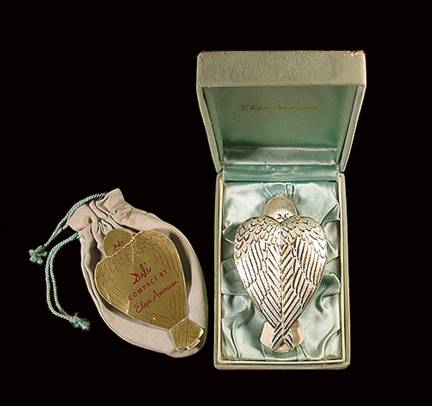

Finally, there are the handle inserts. This item from Revlon would appear to be a regular hand mirror, but the lipstick is cleverly hidden in the handle. It was introduced in 1950 as the “biggest news in lipsticks since swivels were born”. How very exciting.

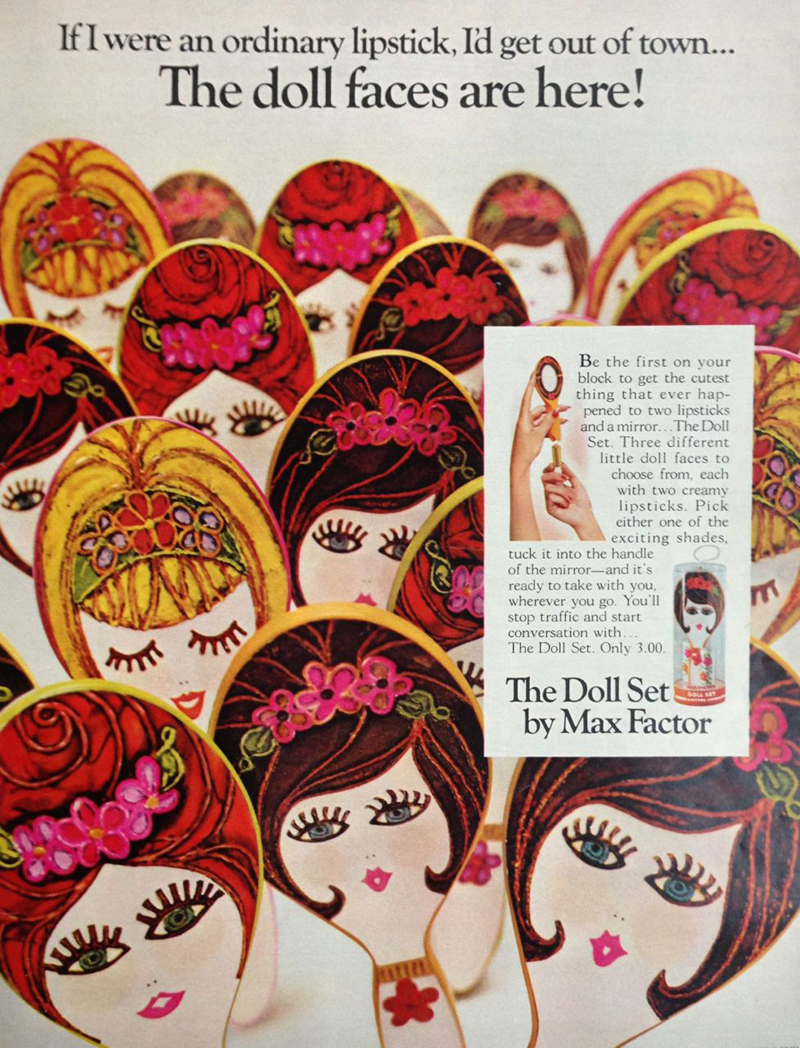

Of course, Max Factor upped the design ante with their “Doll Set” lipsticks, which were introduced in 1967.

(images from pinterest)

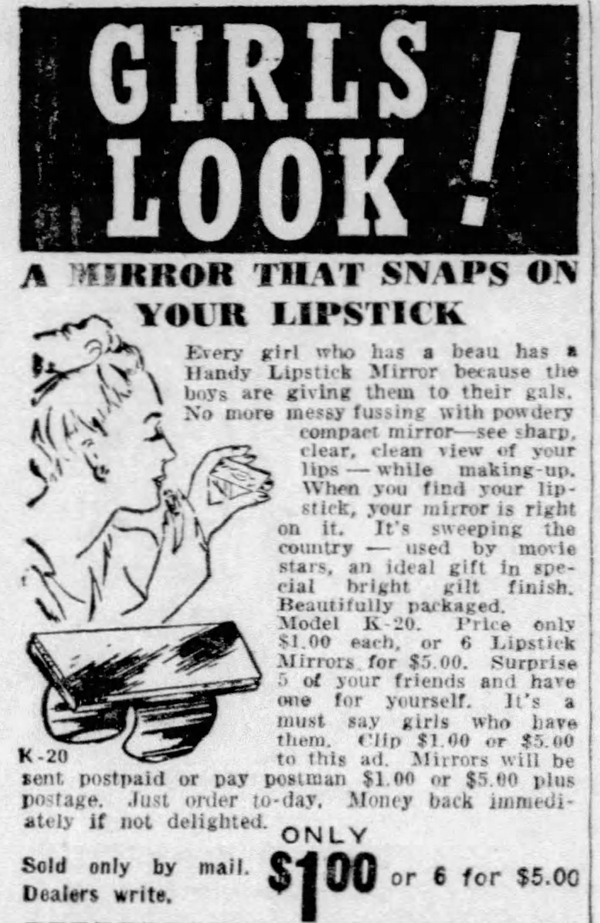

Now that we have a good sense of the types of mirrors that were available, let’s spend a little time thinking about why they were made, or at least, why the advertising claimed they were the greatest things since sliced bread. The first reason built-in lipstick mirrors were a necessity – again, according to the advertising at the time – was the ease provided by a fused lipstick and mirror. Presumably women who wore lipstick also would have also carried around mirrored powder compacts, which could be used for lipstick touch-ups. Fumbling around in your purse for a mirrored compact when you just needed to touch up your lips and not your face powder, apparently, was too difficult to handle on a regular basis. As this 1935 newspaper blurb states, “Keeping lipstick and mirror together is the biggest trouble.” Oh, the horror! (Bonus points for the blatant racism at the beginning of the piece.)

Such a “harrowing experience” to not be able to find a mirror!

The second reason was that the lack of digging around for a mirror meant lipstick could be applied more discreetly, you know, for “when you want to sneak a look while the boyfriend’s back is turned.” (More bonus points for the weight/food shaming piece below the lipstick article.) Much like lipstick tissues, lipstick mirrors were meant to be used to avoid an etiquette faux pas.

This 1940 column takes the idea of discretion a step further. As we’ve seen time and time again, a woman’s makeup habits are dictated by what men think. “We suspect that the bold-face manner of applying lipstick is due for a set-back as a table pastime. Recently we heard more than one rumor that men are expressing a dislike for the practice. And it is a smeary, messy looking operation for a beloved with his own dreams about a natural beauty. Better keep him, if not guessing, then not too much in-the-know about your coloring source.” Heaven forbid a man actually see a woman mend her lipstick! Ladies, please keep your silly frivolous face painting to yourself so as not to ruin TEH MENZ’ unrealistic expectations of so-called natural beauty. I can’t roll my eyes hard enough.

Thirdly, one can’t be seen with a beat-up compact. Women should always present the prettiest possible cosmetic cases when in public. Seriously though, at least this 1956 clip is straightforward in proclaiming that a lipstick mirror is merely aesthetically pleasing instead of a necessary accessory in the battles against flaunting your makeup application and a messy purse in which no separate mirror can be easily unearthed. Just a little dose of “extra glamour”.

And of course, let’s not forget that as part of their goal of making a healthy profit, beauty companies are forever trying to invent another superfluous gadget or product and declaring it the next must-have. Perhaps lipstick mirrors were the mid-century version of vibrating mascaras. In any case, despite the lack of popularity for the built-in lipstick mirror as well as the cynicism of modern-day makeup wearers like myself, several brands forged ahead with attempting to resurrect the lipstick mirror over the past 20 years or so.

In late 1999, with much fanfare, Givenchy introduced their Rouge Miroir lipstick designed by by sculptor Pablo Reinoso. Reinoso became Givenchy’s Artistic Director for their fragrance and beauty line shortly after the lipsticks’ release. The March 2000 issue of Vibe magazine proclaimed the sleek, futuristic design to be the height of convenience: “No more knives or rearview mirrors”. Wait, who uses a knife to apply lipstick?!

(image from amazon.com)

A year or two later, Estée Lauder launched their Pure Color lipstick line. I believe these mirrored cases came out in the mid-2000s when Pure Color lipsticks were at their height.

(image from amazon.com)

Some more recent examples I found include this mirrored tube from Kailijumei, a brand best known for their “flower jelly” lipsticks.

(image from kailijumei.com)

Guerlain’s Rouge G series was introduced in the spring of 2018 and comes in a variety of collectible cases (and, duh, I’m working on acquiring them all). The mechanism is similar to Stratton’s in that they won’t close unless there’s a lipstick bullet inside. While practical, it makes for quite the hassle to take photos of the cases only as they keep popping open. I have to tape them closed, which is a less expensive option than buying lipstick bullets to go in each case.

Finally, I spotted this folding lipstick mirror from J-beauty brand Creer Beaute, which was included in their 2018 Sailor Moon-themed collection.

(images from alphabeauty.net)

Still, these designs are not nearly as common as their predecessors from the early-mid 20th century. Why did the popularity of the built-in lipstick mirror fade over time? One theory is that lipstick packaging with built-in mirrors is more expensive than non-mirrored packaging, and therefore, not as appealing to consumers. Guerlain’s Rouge Gs, for example, cost $55 ($33 for the bullet and $22 for case) while their KissKiss lipsticks are priced at $37. Going further back in time, Elgin’s spring-loaded mirrored case by itself was $5.50, while the price of an average lipstick was $1.10. Why pay for a mirrored lipstick case if you (most likely) already have another mirror available? Yes, you might have to dig around in your purse a bit, but at least it won’t be lighter for having spent money on a lipstick/mirror combo. This theory could also explain why clip-on mirrors were seemingly everywhere, as they were the cheaper route to fusing lipstick and mirror.

Another theory for the continuing disinterest in built-in lipstick mirrors could be that for the last 5-10 years there’s been increasing demand for less, or at least recyclable, packaging. While some higher-end brands are refillable, most lipsticks sold with a built-in mirror don’t appear to have a refill option, and consumers may be less likely to buy a mirrored lipstick tube knowing yet another packaging component will eventually end up in the ocean. Plus, while the new designs are relatively slim, they’re still bulkier than lipsticks without built-in mirrors. The majority of beauty consumers, myself included, don’t want anything taking up more room in their purse or makeup bag.

Finally, I believe beauty consumers are savvier than they were in the early days of the industry and are less susceptible to marketing and gadgets. A built-in lipstick mirror may have been considered revolutionary in the ’40s because swivel tube lipstick had been invented just a few decades prior, but by the ’70s these mirrors may have seemed old hat. So certainly by the 21st century we know these designs are not truly a breakthrough, nor are they anything that would be considered a necessity. I featured no fewer than 6 Kailijumei lipsticks in the Museum’s spring 2017 rainbow-themed exhibition, and just now noticed there were mirrors on the tubes. The fact that the mirror didn’t even register with me, a person who enjoys re-applying her makeup and has spent countless hours poring over product packaging, until now when I’m actually discussing lipstick mirrors shows just how unnecessary a built-in lipstick mirror is. And again, the majority of beauty consumers is likely to be carrying a compact mirror anyway, rendering a lipstick with a built-in mirror redundant. We also know that makeup companies update older designs and market them differently to see what sticks. To cite Guerlain’s Rouge G, the description at the website highlights how the user can select both the color and case to suit their individual taste. “Every woman is unique…choose your lipstick from a wide range of shades to match your look: from the most nude to the most extravagant. Choose your case from an array of styles – from the most timeless to the most trendy”. Rouge G has the same basic mechanism as the spring-loaded lipsticks of yore – it’s especially similar to Max Factor’s Hi-Society with the array of designs – but the marketing focuses on the customizable aspects (a concept that has spiked in popularity over the last two or so years…I’ve been meaning to write something about the craze for name engraving/customization) rather than the newness and convenience of a dedicated lipstick mirror.

What do you think of the built-in lipstick mirror? Would you consider it a must-have? While I certainly appreciate the aesthetics, it’s nowhere near a necessity for me.

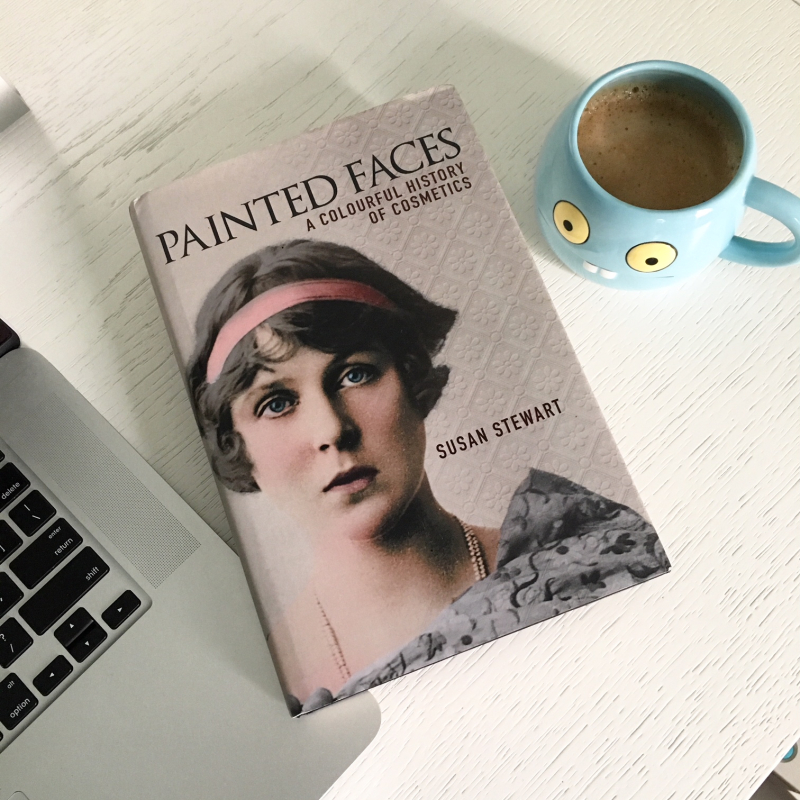

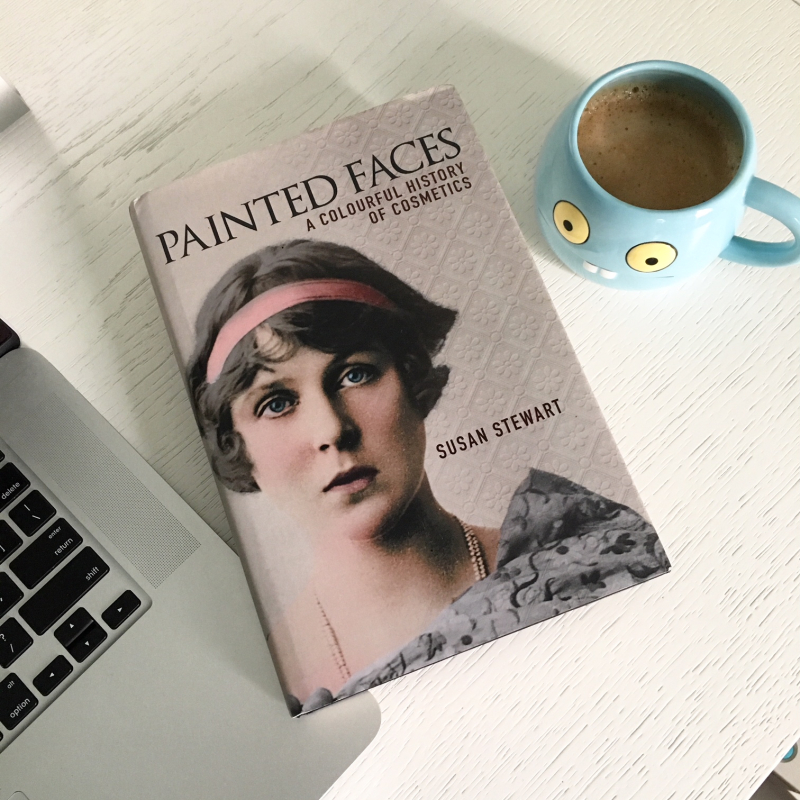

Before I get to my review of Susan Stewart's Painted Faces, I must disclose that I received a copy for free from the author. In no way, shape or form did getting it for free influence my review, nor was it intended as a bribe for a positive one – I believe I was given a copy in exchange for me lending photos of some of the Museum's collection to be included in the book. Not only did Dr. Stewart provide an autograph, she also included me in the acknowledgements, which was incredibly kind.

Again though, I'd like to reiterate that this did not sway my opinion of the book at all. Now that that's out of the way, I can dive into the review.

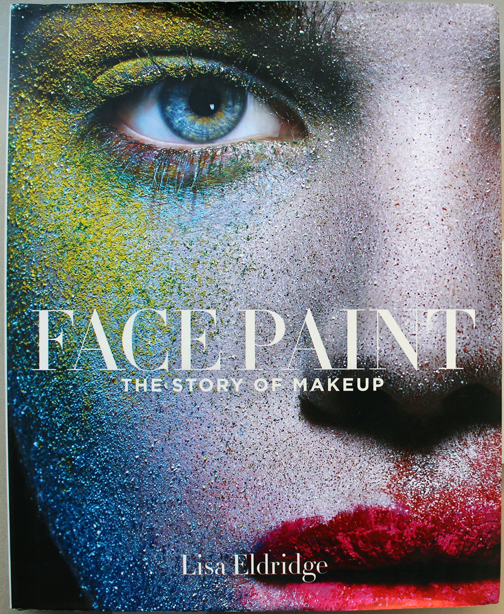

The goal of Painted Faces is much the same as Lisa Eldridge's Face Paint in that it strives to provide a history of makeup from ancient times to the present day. However, a trained scholar/historian approaches this vast topic in a markedly different way than a makeup artist such as Eldridge. Neither perspective is better or worse than the other; ways to tell the story of makeup are nearly as varied as the people who wear it. Nor do I believe one has to have a set of particular credentials to write accurately and compellingly about makeup history, as I believe it comes down to a matter of preference for a certain writing style. As we saw with her first book, Painted Faces is more academic than Face Paint and relies on highlighting the economic and sociological aspects behind various beauty practices, whereas Eldridge adopts a more artistic tone, choosing instead to communicate makeup's history by focusing on application and styles as they evolved.

Stewart begins with an introduction (which also serves as the first chapter) summarizing the need to study makeup and beauty practices as it gives valuable insight into history that we may not have considered before. "Because of its wider significance, researching makeup, its uses, ingredients, its context and application, can provide clues not only to the nature and circumstance of the individual but can also help us to interpret the social, economic and political condition of society as a whole in any given period. That is to say, studying cosmetics can further our understanding of history…they are a window into the past and can encapsulate the hopes and ideas of the future. In short, makeup matters" (p. 8 and 10). Can I get an amen?! Stewart also carefully sets the parameters for the book, outlining the sources used and why she is primarily writing about cosmetics in the Western world.

Chapter 2 is essentially a condensed version of Stewart's previous tome on cosmetics in the ancient world, which doesn't need to be rehashed here (you can check out my review of that one to peruse the content). That's no small feat, considering how thorough it was. The next chapter covers the Middle Ages, which is interesting in and of itself since so little information about makeup and beauty exist from this era. As Stewart points out, the rise of Christianity meant people were no longer being interred with their possessions as they were in ancient Greece and Rome – these artifacts provided a wealth of knowledge about beauty practices then. Thus, any time after the spread of Christianity and before the modern age historians must rely primarily on texts, such as surviving beauty recipes and classic literature, rather than objects to infer any information about the use of makeup and other beauty items. The dominance of this religion also meant even more impossible beauty standards for women and more shame for daring to participate in beauty rituals. "According to medieval religious ideology, wearing makeup was not only the deceitful and immoral – it was a crime against God" (p. 60). The other interesting, albeit twisted way Christianity affected beauty is the relentless belief that unblemished skin = moral person. Something as innocuous as freckles were the mark of the devil, and most women went to great lengths to get rid of them or cover them so as not be accused of being a witch. I shudder thinking about those who were affected by acne.

Chapter 4, which discusses beauty in the late 15th and early 16th centuries (i.e., approximately the Renaissance) presents the continuation of certain beauty standards – pale, unblemished skin on both the face and hands, a high forehead, barely there blush and a hint of natural color on the lips- as well as judgement of those who wore cosmetics. As we saw previously, it's the old "look perfect but don't use makeup to achieve said perfection" deal – women who wore makeup were viewed as dishonest, vain sinners. But one's looks mattered greatly in the acquisition of a husband, so many women didn't have a choice. "Clearly a woman had to get her makeup just right not simply for maximum effect but to avoid getting it wrong and spoiling the illusion of youth and beauty entirely, a fault that could cost her dearly in terms of wealth, status and security" (p. 94).

However, there were some notable differences between the Renaissance and medieval periods. For starters, due to inventions such as the printing press, beauty recipes were able to be much more widely disseminated than they were previously. Increased trade meant more people could get their hands on ingredients for these recipes. Both of these developments led to women below the higher rungs of society (i.e. the middle class) to start wearing cosmetics. So widespread was cosmetics usage at this point, Stewart notes, that the question became what kind of makeup to wear instead of whether to wear it at all.

This chapter was probably the most similar to those on Renaissance beauty in Sarah Jane Downing's book, Beauty and Cosmetics: 1550-1950. Given the lack of information regarding cosmetics during this time period, both authors had to draw on the same sources to describe beauty habits. However, as with Eldridge, the approaches Downing and Stewart take are slightly different. Once again, Stewart opts for a straighter historical approach whereas Downing looks more to paintings and literature of the time, and doesn't take quite as deep a dive into the larger social and economic forces at work. There's also not much overlap between the descriptions of recipes and techniques, as you'll find different ones in each book. For example, one that was mentioned only in passing in Downing's book was using egg white to set makeup. I'm thinking of it as a early version of an illuminating setting spray (although obviously it was brushed on, not sprayed in a bottle) as it lent a slightly luminous, glazed sheen. Stewart points out that it also caused one's face to crack, thereby eliminating the wearer's ability to make any sort of facial expression. It seems certain beauty treatments, whether egg white or Botox, occasionally come with the side effect of suppressing women's expression of emotion. Coincidence? I think not.

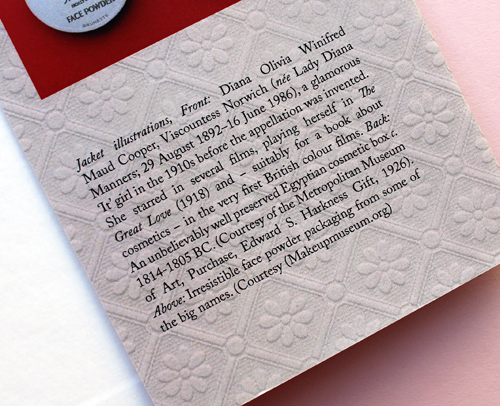

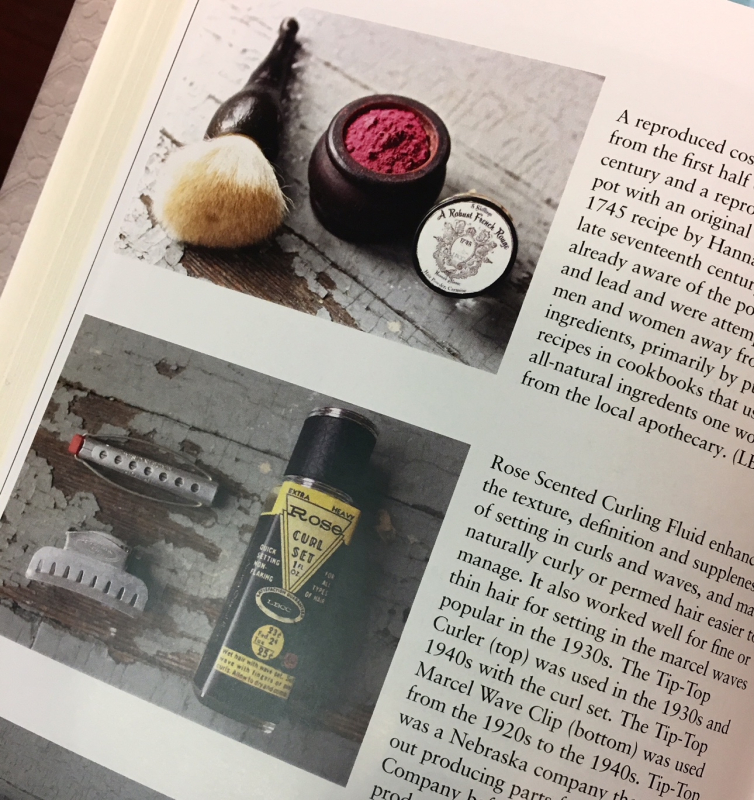

Chapters 5 and 6 are tidily sequential, discussing beauty during the the 17th and 18th centuries, respectively. As in the Renaissance, both eras witnessed significant growth in the number of women who wore makeup due to technological advances and increased trade. Growing literacy rates drove demand for the new medium of ladies' magazines. Pharmacies selling raw materials to make beauty treatments had started to crop up in the 17th century and their numbers increased dramatically by the beginning of the 18th century. Not only that, pharmacies and chemists started offering their own pre-made formulas, and these goods became commercially exported to other countries. The widespread sale of these products came with several undesirable effects: counterfeit cosmetics and downright false claims about the product's efficacy.

The 1700s also saw the rise of excessive, decidedly unnatural makeup being worn by members of the aristocracy in both France and England, followed by a post-French Revolution return to more subtle makeup in the early 1800s. This brings us to Chapter 7, which outlines the myriad changes leading to what would become the modern beauty industry, including department stores, industrialization and the new commercial market of the U.S. As for beauty standards, a natural look was still strongly preferred by both men and women, with the emphasis in terms of products on skincare rather than color cosmetics. Here's a literal lightbulb moment: despite my research on Shiseido's color-correcting powders, in which I learned some were meant to counterbalance the effects of harsh lighting, I had completely overlooked the influence of artificial light on the skyrocketing production of face powders. "Suffice it to say that in the early years of the twentieth century, the use of artificial light in homes of the wealthy as well as in public places such as theatres and concert halls would become more widespread, in the latter years of the nineteenth century there was already an understanding that to make the best impression, makeup needed adjusting to suit the light, whether it be natural or artificial" (p.198).

Chapter 8 leads us into the 20th century. While there are more detailed accounts of makeup during this time, Stewart does an excellent job describing the major cultural and technological influences that shaped modern beauty trends and the industry as a whole. I was very impressed with how she was able to narrow down the key points about 20th century beauty without regurgitating or simply summarizing other people's work. Some of the information presented is familiar, of course, but the manner in which it's arranged and categorized sets it apart. It just goes to show that everyone's individual background equals an infinite number of ways to tell the story of makeup.

I'm partial to this chapter since the items I took photos of for the book are all from the 20th century. :)

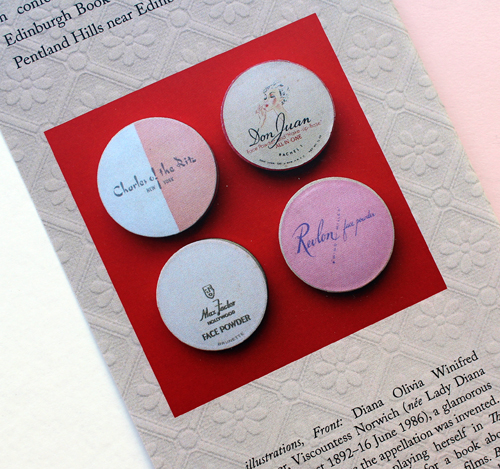

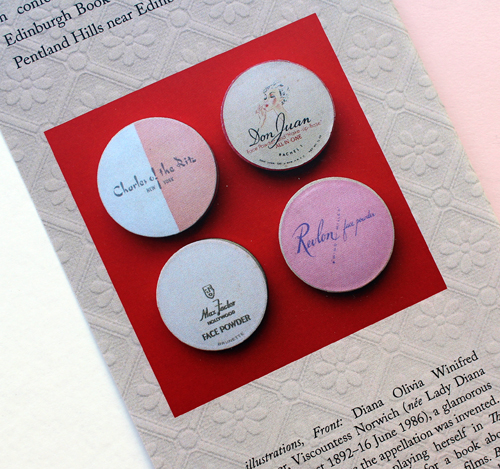

Here are some powder boxes on the dust jacket.

While I was deliriously happy to see some of the Museum's items in a real published book and get credited for them, I was also pleased to see photos of other pieces as well. Their inclusion in addition to illustrations was a bit of an upgrade to Stewart's previous book. This is a minor issue to be sure, as I believe solid writing more than makes up for a lack of photos, but they are a nice touch if available.

The last chapter serves as an addendum in which Stewart reflects on how the past, present and future of beauty are linked, noting that while some things have stayed the same – the use of ancient ingredients in modern formulas, the connection between health and beauty – 21st century attitudes towards cosmetics represent a significant change from earlier times.

Overall, this is a more scholarly history of makeup than we've seen before, but by no means dry and boring. Stewart's gift for wading through hundreds of historical documents and neatly consolidating the major social, economic and cultural forces that shaped makeup's history, all while sharing fascinating snippets such as ancient beauty recipes and anecdotes from people who lived during the various eras she covered, makes for a thoroughly engaging read.

Will you be picking this one up?

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

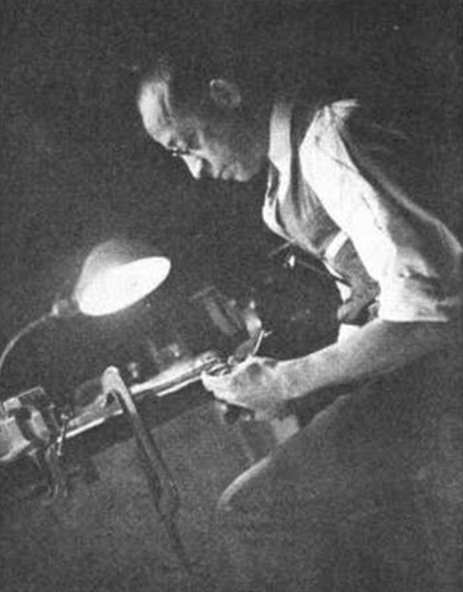

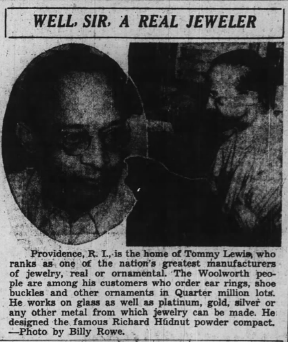

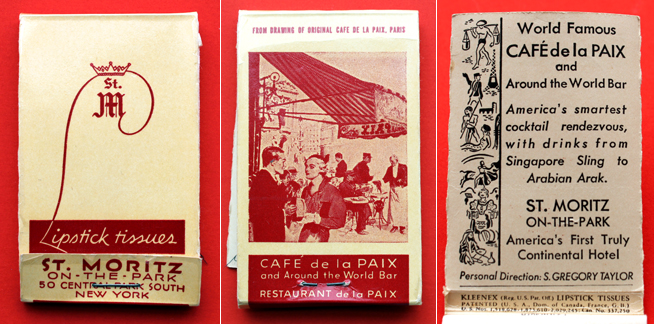

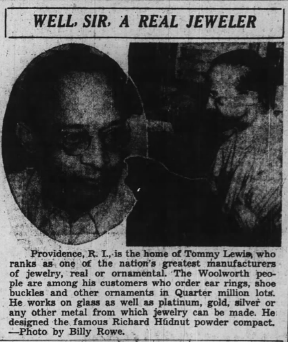

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

According to another article written in 1935 that I found online, Lewis was born into an impoverished family in Providence, Rhode Island. Undaunted by his circumstances and without the support of his parents or siblings, he attended RISD with the hopes of becoming a jeweler, earning a scholarship in the process. After graduating he worked for a leading jewelry manufacturer in Providence for several years, then struck out on his own.

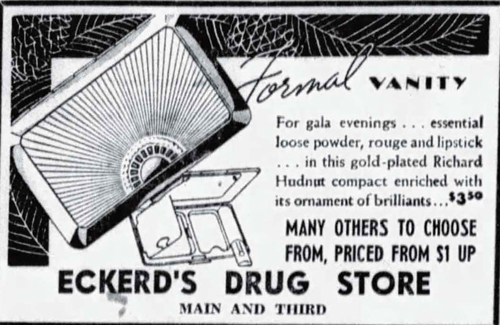

I was unable to find the date he started his company or much other information besides what was in these two articles. The 1935 online article says that he started his business 27 years prior, so I’m assuming he established it in 1908; however, the 1938 article says that he had been in business for 26 years, so maybe it was 1912. And there’s no information on his relationship with Hudnut other than what was in that article, so when he started making compacts for them is unclear. The only (rather patronizing) mention is as follows:1 “Visit the cosmetics department in any first class store, ask the clerk to show you a Richard Hudnut powder compact and then surprise him by telling him that he is looking at the work of a [Black] man. Everyone of those compacts was designed and produced here in a plant at 19 Calendar Street, the home of the Lewis Jewelry Manufacturing Firm. The same is true of their perfume bottles, for Mr. Lewis works on glass as well as platinum, gold, silver or any other metal from which jewelry or ornaments can be made. The Richard Hudnut people are among his biggest customers, but not his most consistent. That honor is reserved for other jewelry manufacturers who regularly send in their commissions for original designs in bracelets, watch chains and other novelty jewelry.” So it seems that while Hudnut was not the biggest source of business for Lewis’s company, we know that he was designing all of their compacts by 1938, and presumably earlier. When I purchased these compacts for the Museum I made sure to select ones that I could get specific dates for, i.e. compacts that were plausibly produced by Lewis given the approximate timeline, and also ones that seemed to be the most jewelry-inspired.

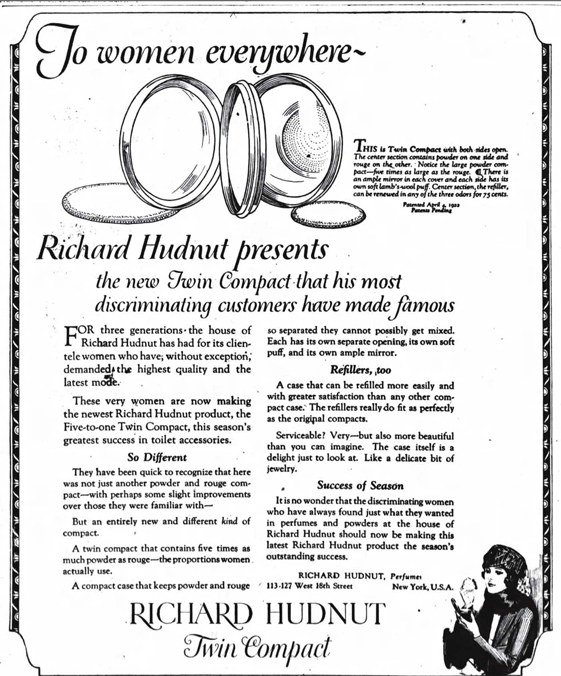

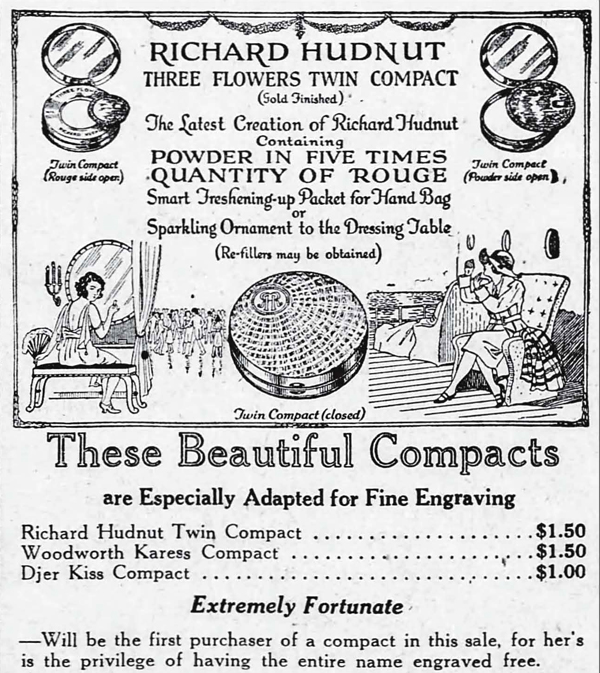

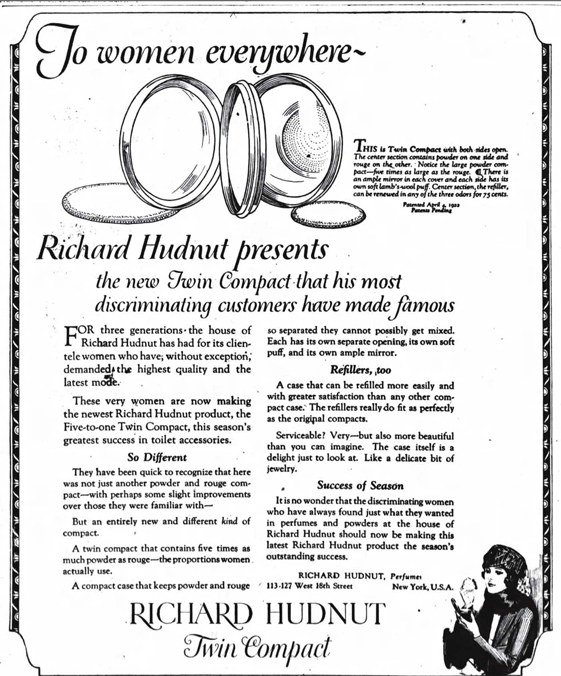

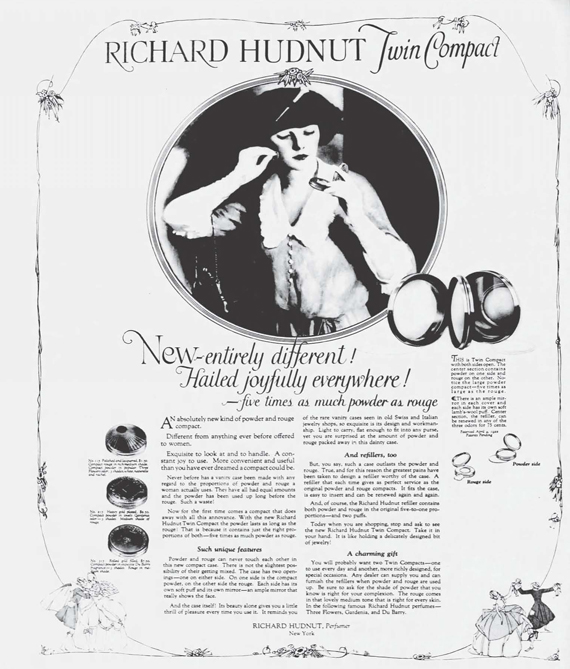

First up is the original “twin” compact, which was introduced in late 1922. I didn’t realize this until after I bought it, but this double case was designed by a man named Ralph Wilson in 1921 and patented in early 1922. Wilson was the New York representative for Theodore W. Foster and Bro. Company, a prominent compact and jewelry manufacturer. Foster, like Lewis, was also based in Providence, so maybe there might be some connection between this company and Lewis’s – perhaps this is the company Lewis worked for after graduating from RISD? In any case, we have proof that the twin compact was created by a company other than Lewis’s, so this is not his work. I still like to think, though, that Lewis may have apprenticed with Foster, grew familiar with Hudnut’s aesthetic and went on to earn the company’s favor over Foster.

How cool is this? You flip over the blush and there’s powder on the other side. Genius.

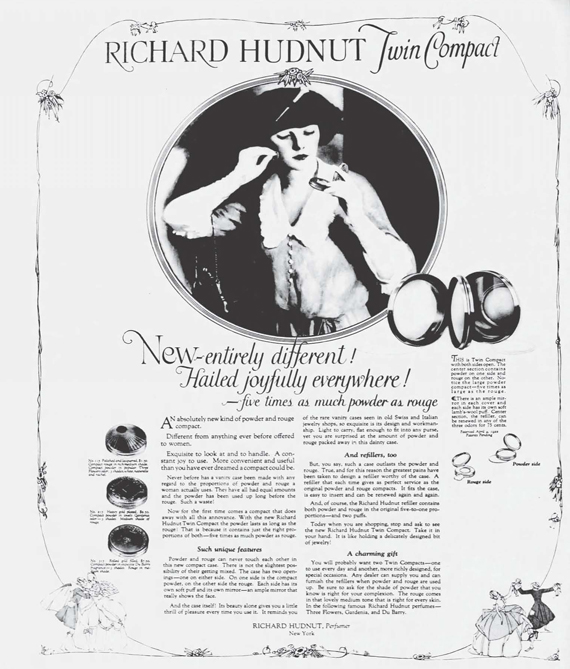

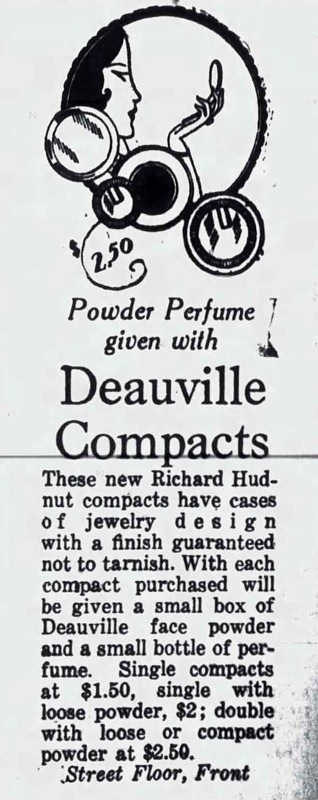

Hudnut’s Deauville fragrance was introduced in 1924. Again, no telling whether this was done by Lewis, but probably not given that it’s basically the same interior mechanism as the earlier twin compact.

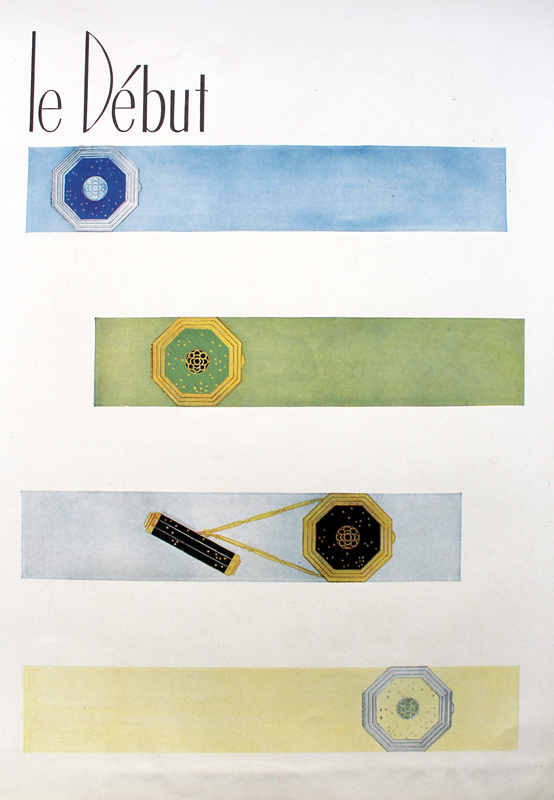

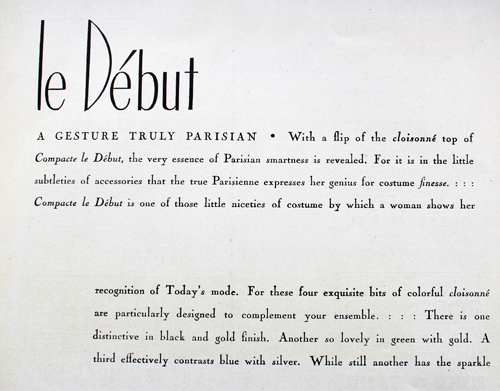

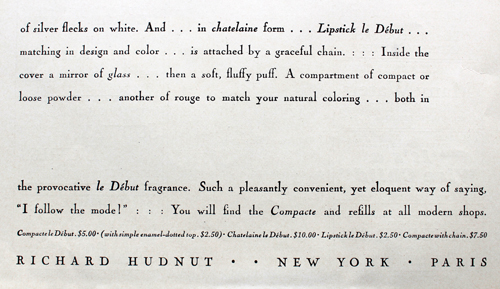

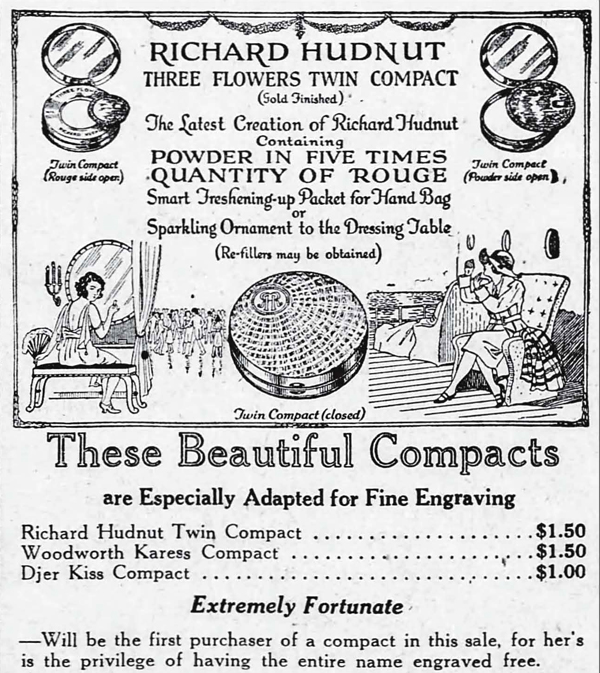

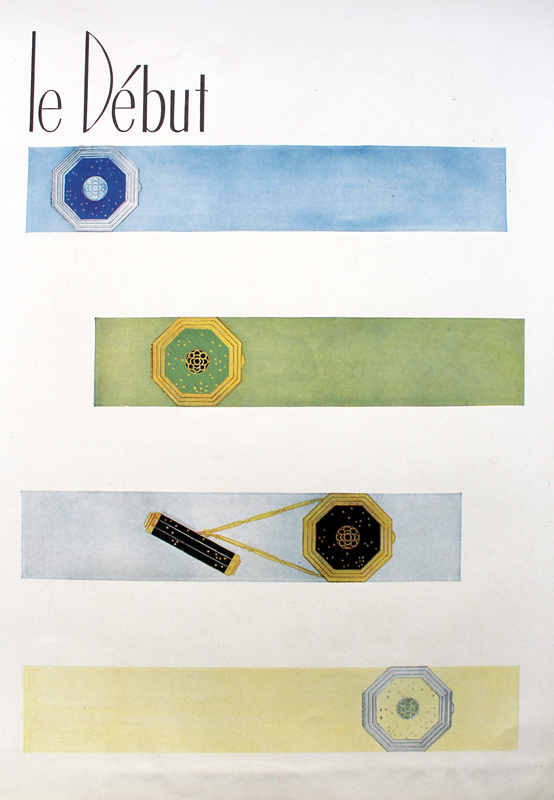

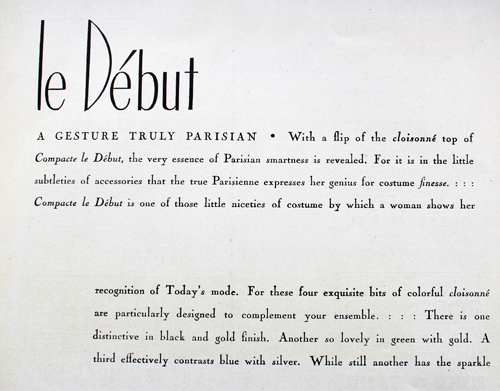

Le Début, a fragrance available in 5 different variants that were color-coordinated to their bottles and powder compacts, well, debuted in 1927. I was fortunate enough to track down an original ad for these beauties. They’re actually pretty common – I was able to find all the colors shown in the ad – but in the end I thought the black one was the most elegant. (Okay, I really love the silver one too!)

In the 1938 photo below it states that Lewis designed the “famous Richard Hudnut compact”, but I really have no idea which one they’re referring to. It could be Le Début, or it could be the “triple vanity” compacts designed in the mid ’30s.

This enameled, oh-so-Deco case came out in 1936, according to the newspaper ads I found, and the last mention of it was in 1938. Again, it’s funny how certain objects call to you. This one was also available in a variety of colors, but I just knew the red belonged in the Museum.

The triple vanities had three compartments for powder, blush and lipstick.

The ad also mentions jewelry several times, so I’m hopeful it was made by Lewis’s hand.

Lastly, I picked up this stunner, which dates to about 1939. Evidently between this one, the Three Flowers compact and the silver Evans compacts I have a thing for sunburst patterns, probably because they remind me of glorious sunny days.

How exquisite is this jewel detail? And in such impeccable shape for a nearly 80 year-old compact – it’s mind-boggling that none of the stones are missing.

To give you a sense of how dainty and small these triple vanities are, here they are with one of NARS’ highlighting trios.

Getting back to Lewis, I can’t say for sure whether his company was responsible for any of these compacts; I can only hope at least some of these jewelry-inspired designs were his. The fact that the 1935 article doesn’t specifically mention Richard Hudnut makes me think that perhaps Lewis wasn’t designing compacts for Hudnut until somewhere between 1936-1938. But it’s also entirely possible he had been producing compacts for them for years. In any case, I want to highlight just how difficult it was for a Black man in the 1900s to not only get out of poverty, but graduate from one of the top design schools in the country AND start his own business that eventually employed up to 60 workers in the busy seasons. As the 1935 profile states: “But jeweler, designer, silversmith? What chance would he have? Where could he work? Who ever heard of a [Black] man, a designer, a master craftsman in the jewelry trade of all trades! One can imagine what would have been Lewis’s fate if his ambitions had been left in the hands of some of the so-called vocational guidance counselors who are at the present time shaping the lifework of many [Black] students in the public schools of our large cities. According to the formula which they use, there are no [Black] jewelers now in existence, hence no future; it would be impossible for a [Black] silversmith to get a job since he cannot belong to the union, and the white jewelers would not employ him anyhow.” Through incredibly hard work and innate talent, Lewis persevered, not only becoming a success himself but also helping others do the same. Most of his employees were Black, and Lewis provided them with better wages than other jewelry firms in Providence as well as training.

I just wish I could have found more information and photos to make for a somewhat complete biography. Searching online for Lewis’s company yielded nothing, as did basic searches for Lewis himself. I ended up contacting the Rhode Island Historical Society and they kindly provided census records indicating his year of birth (1880), but said they didn’t have any business records related to Lewis’s company, which I think is bizarre. If it was as prolific as the articles claim it was, and if it really did provide hundreds of thousands of pieces of costume jewelry to the likes of Saks and Woolworth’s and compacts for Hudnut, I find it very strange that there are absolutely zero traces of his company left save for these two profiles. Especially since the 1938 article even gives the address of his workshop – with that specific type of information there should be historic maps or architectural records listing it. He also apparently had over 200 patents to his name, none of which I was able to find. I guess the saddest part is that there are tons of other stories like Lewis’s, and we simply don’t hear about them. So many histories for non-white people are erased or buried, and I really wanted to bring Lewis’s story to the surface because it was truly outstanding (and not only because it’s Black History Month…I just so happened to find the newspaper article around a month ago and thought the timing worked out nicely). I really hope this post didn’t come across as patronizing or me highlighting a “token” Black person.2 I find Lewis’s story impressive not because I can’t believe a Black man could ever be creative and intelligent enough to start a jewelry firm, but because of all he had to overcome to achieve his goals. “Perhaps it is the memory of a [Black] boy with a dream to become a jeweler, a silversmith, a designer, a [Black] boy who kept his dream despite the doubts of his family from within and racial prejudice from without. For Thomas Lewis is an artist and so he believes in young men and young women with dreams.”

Thoughts?

Update, 11/24/2022: One of the Museum’s Instagram followers alerted me to a video made by a vintage compact collector who mentioned Tommy Lewis while showing some of her Hudnut collection. It got me thinking whether anything else on Lewis had been discovered and lo and behold, two students from Rhode Island College were able to unearth some more information, including a map showing where his store and factory were! While it didn’t shed any light on Lewis’s relationship with the Hudnut company, their article surely adds more to this important piece of history. Lewis was born on April 5, 1880 and graduated from RISD in 1902. In 1925 a lacquer explosion caused a fire at Lewis’s shop located at 171 Eddy Street, which damaged much of the building. I’m wondering if some of the early business records were lost in that fire. Throughout his life, in addition to providing training and employment for Black workers, he was a philanthropist and active in the YMCA and other community organizations. Lewis passed away in 1958. I can only hope someone writes a full biography of this exceptionally talented man, but in the meantime sure to check out the article at rhodetour.org. Oh, and they even included the Makeup Museum’s original article as a “related resource”. I’m so honored!

1 I spent several hours googling whether it was acceptable to type the word “c*lored” if I was quoting from an old newspaper article. In the end I realized I personally didn’t feel comfortable using it even if it was a quote, so I replaced it with “black”.

2 I rarely, if ever, highlight makeup histories featuring people of color, i.e. Madam C.J. Walker, Annie Turnbo Malone, etc. because I’m not sure whether it’s okay for a white person to do that – while I think their stories absolutely need to be heard and recorded, once again I fear that it would come off as whitesplaining or tokenizing if I attempted to write about them. In the case of Tommy Lewis, there was such scant information available I’d figure I’d make an exception in order to at least introduce him and his work.

Save

Save

Save

Save

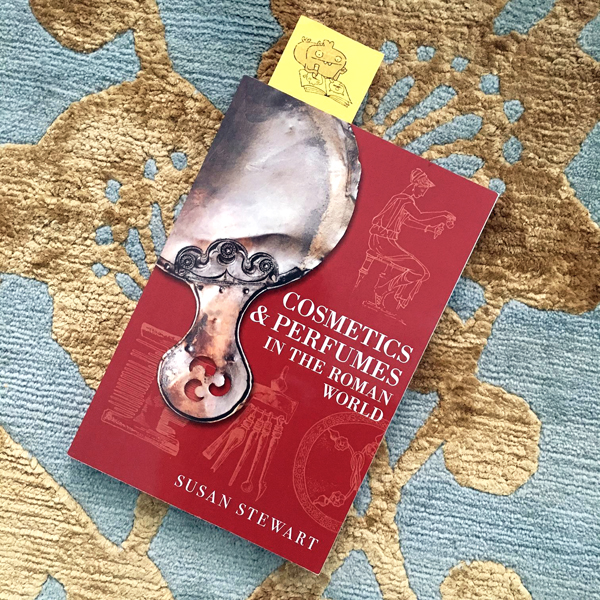

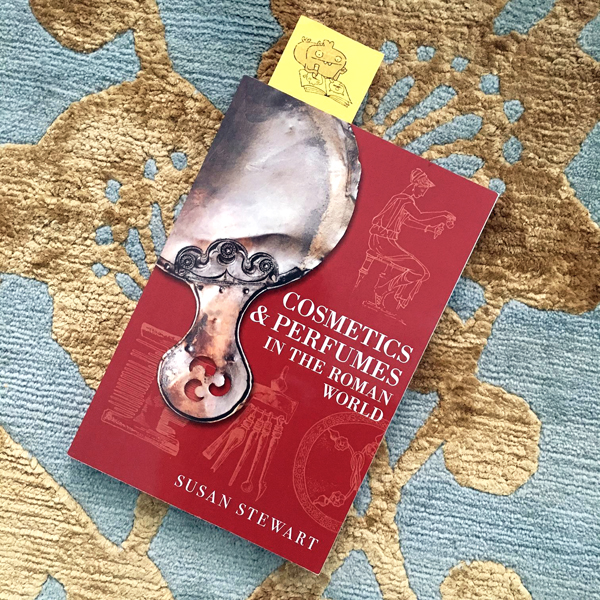

I don't know how this tome managed to slip under my beauty book radar. I wasn't aware that this little gem existed until the author followed me on Twitter. Much has been written about the modern beauty age (20th-21st centuries), but there are not many in-depth resources available on beauty practices prior to that. Fortunately, Dr. Susan Stewart, an independent scholar and librarian at Scotland's Broxburn Academy, is here to help fill in the gaps. Drawing on literary texts, visual arts and material objects as primary source material, Cosmetics and Perfumes in the Roman World presents a thorough history of makeup and fragrance usage during the Roman Empire (roughly 1-300 A.D.)

The introduction also serves as Chapter 1, which is an overview of the author's sources, geographic areas and time period that are covered – basic but necessary. Chapter 2 is probably my favorite, since it summarizes the ingredients used in cosmetics as well as the beauty ideals of the time. Empresses and mythical goddesses set the beauty standards that most women aspired to. Unsurprisingly, the key beauty goals for women were identical to today's – clear skin, large eyes and silky hair. And lest you think our obsession with a youthful appearance is a fairly new scourge, this chapter highlights several recipes for wrinkle creams and hair dyes. Even some ingredients haven't changed much; mascara and brow filler were made from soot, which is almost identical to what we think of as the first modern mascara concoction. Stewart also notes that most of the recipes and techniques date back even further, as the Romans borrowed them from the ancient Egyptians.

Chapter 3 tackles the health and hygiene aspects of Roman beauty products. While I prefer reading about actual face paint, this chapter is important since it provides the foundation (see what I did there?) for understanding modern cosmetics. Since its infancy the beauty industry has linked good health with attractiveness: glowing skin, bright eyes, a pleasant scent and white, even teeth are all still considered markers of beauty. If one was beautiful and smelled nice they must be healthy and vice versa. "One's appearance in general is improved by good health and reflects good health; making health a constituent of beauty and beauty in turn a constituent of health" (p.51). One of the most interesting pieces of proof of this belief among the Romans were the images of Venus commonly displayed at bath houses.

Whereas the previous chapters laid out the what and the how, the next two chapters examines the who and the why, i.e. the differences in use of beauty and hygiene products based on gender, race and class power structures, along with society's perception of women who used cosmetics. Needless to say, by and large women were heavily critiqued for wearing makeup for the same reasons we see today. "A woman displayed her inferiority by feeling compelled to improve upon her appearance, her weakness by being tempted by luxury (in the form of expensive beauty products), her obsession with sex by trying to make herself attractive to men other than her husband, her deviousness by disguising her true appearance with makeup and finally, her idleness by having too much time to spend on personal grooming" (p.65). Once again women who wear makeup are vain and shallow, and women generally were expected to look perfect but not use any beauty aids. Same old story, right? Sadly, it wasn't really any better for men; Stewart notes that men who were overly prettified by society's standards were seen as effeminate and unfit to perform traditional men's work. Despite all of these negative perceptions, literally hundreds of makeup/perfume containers and application utensils have been recovered from Roman ruins over the years, which serves as hard evidence that most people engaged in beautification and grooming practices. However, while these items were widely used, class played a significant role in the types of products and their application. As was the case in the early 20th century, a more "natural" look achieved with higher quality ingredients was a mark of the middle and upper classes, while heavy makeup and scent made from cheap, readily available sources were associated with prostitutes (obviously, since the latter couldn't afford more expensive beauty products.)

The last chapter explores the notion of luxury as it relates to cosmetics and perfumes during the Roman empire. As noted previously, given their widespread use among different economic classes, most beauty products weren't luxury items. Male philosophers (especially those damn Stoics) believed makeup and fragrance to be highly unnecessary and therefore luxury goods, but physical evidence suggests this wasn't a widely held view. While empresses and other high-class women used only the "good stuff" made from extremely pricey ingredients, there were many options available at all price points. And this range isn't reflected only in the ingredients but in the containers as well; everything from silver, bronze and clear, colorless glass (high-end) to blue-green glass (the most inexpensive type of container) was used to store beauty products.

All in all, this is a well-researched and fascinating read, and most importantly, it's accessible for the masses. Despite all of the classic literature and art history references, Stewart makes it easy for non-academics to understand. The information is presented in a straightforward yet compelling manner, i.e. there was no boring, bland spouting of one fact after another but rather a narrative that flowed from describing the basics (makeup ingredients, utensils, etc.) to more complex ideas (the cultural and political climate that influenced why and how they were used.) Also, even though I shouldn't be, I'm amazed (and a bit sad) by how little things have changed; beauty standards are still more or less the same as they were 2,000 years ago, despite current efforts to diversify them. My only critique is that I would have liked to have seen more photos rather than illustrations. The drawings were able to communicate the ideas and objects well enough, but they lacked the visual impact photos would bring. I'm assuming museums wanted exorbitant fees to use their photos so the author had no choice but to use illustrations.

Will you be picking this one up? Oh, I almost forgot – Stewart has a new publication on cosmetics history coming out in December, which obviously is already at the top of my Christmas list. ;) Keep your eyes peeled!

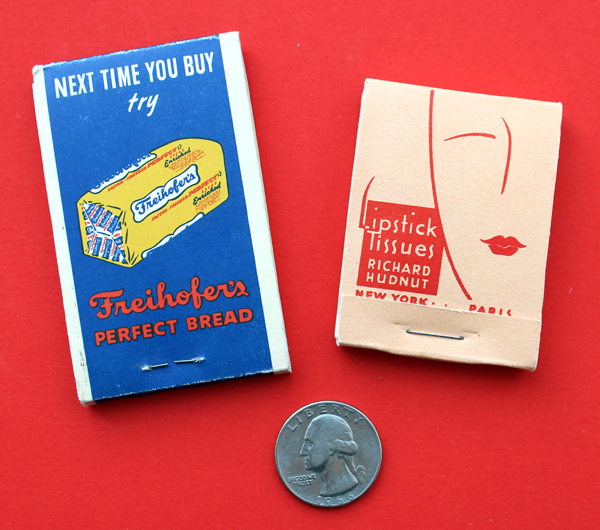

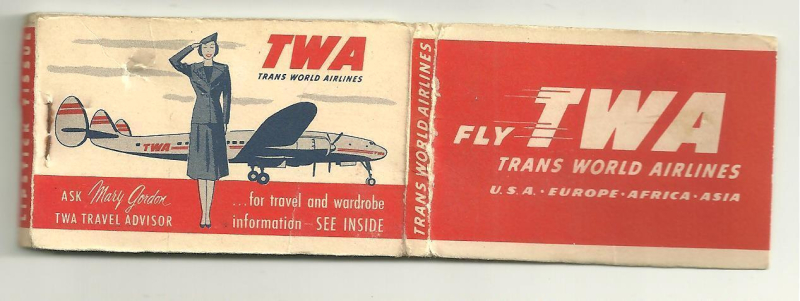

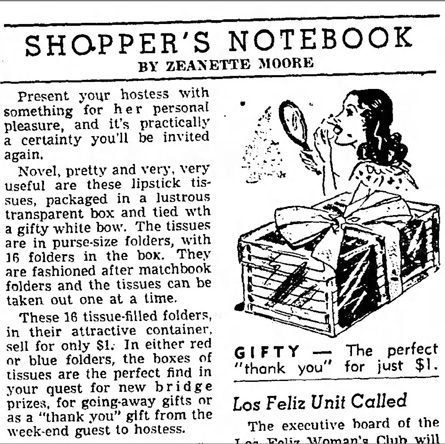

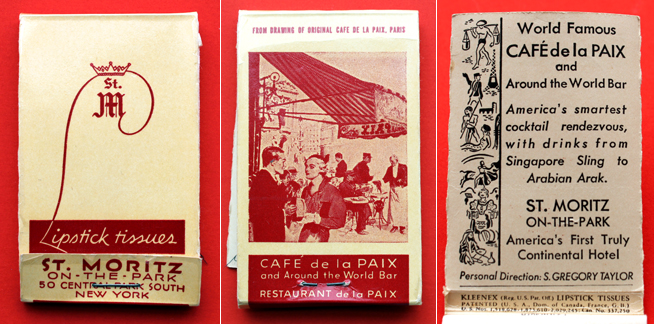

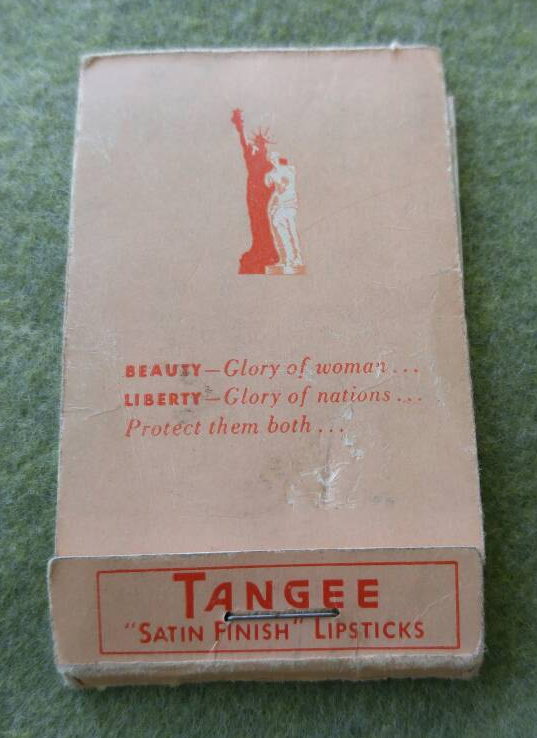

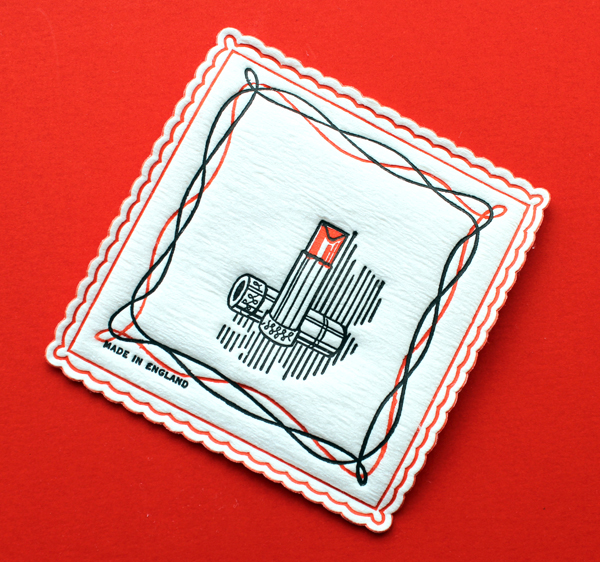

The life of a makeup museum curator is insanely glamorous. For example, a lot of people go out on Friday nights, but not me – I have way more thrilling plans. I usually browse for vintage makeup at Ebay and Etsy on my phone while in bed and am completely passed out by 8pm. EXCITING. It was during one of these Friday night escapades that I came across a fabulous box of vintage lipstick pads and naturally, that sent me down quite the rabbit hole. Today I’m discussing a cosmetics accessory that has gone the way of the dodo: lipstick tissues. This is by no means a comprehensive history, but I’ve put together a few interesting findings. I just wish I had access to more than my local library (which doesn’t have much), a free trial subscription to newspapers.com and the general interwebz, as anyone could do that meager level of “research”. I would love to be able to dig deeper and have more specific information, but in lieu of that, I do hope you enjoy what I was able to throw together.

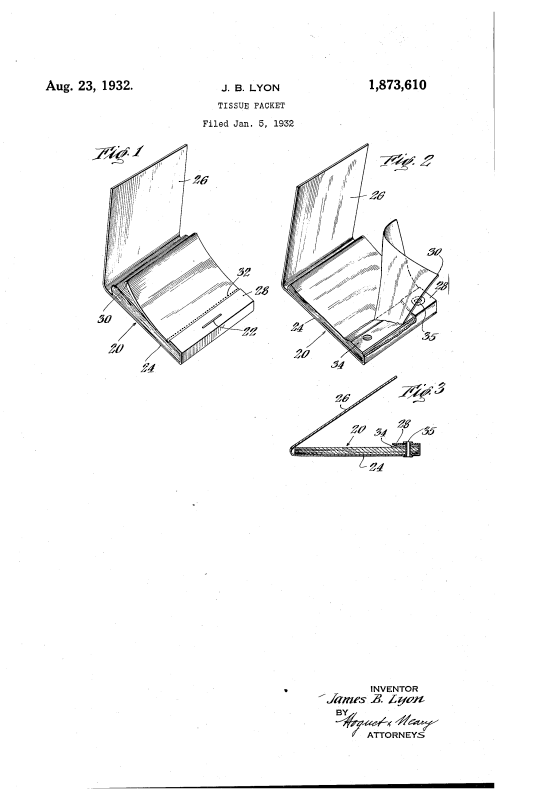

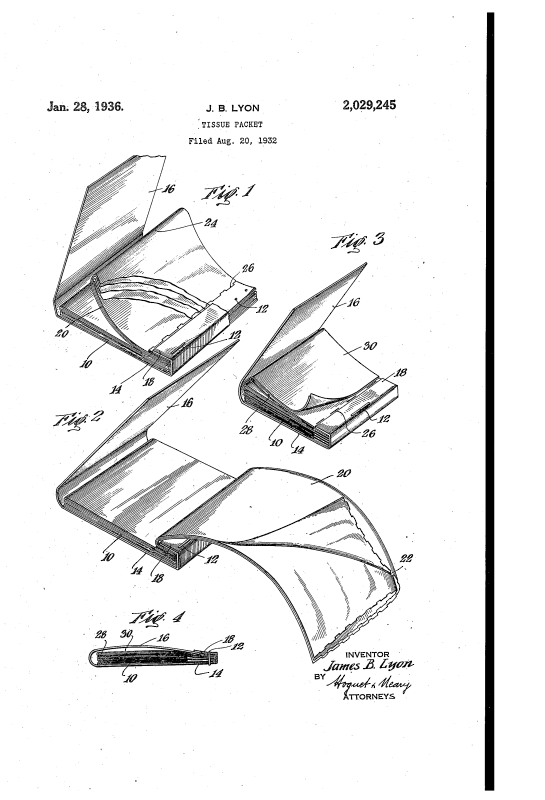

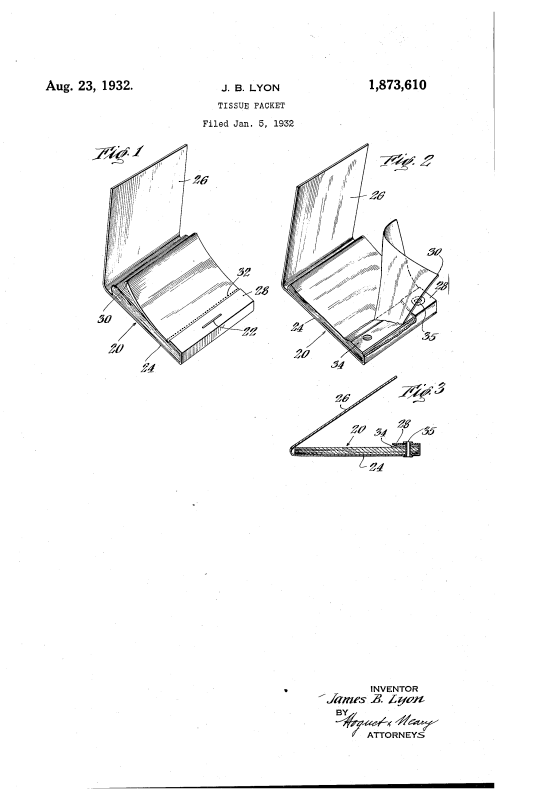

The earliest mention of lipstick tissues that I found was January 1932. It makes sense, as several patents were filed for the same design that year.

(images from google)

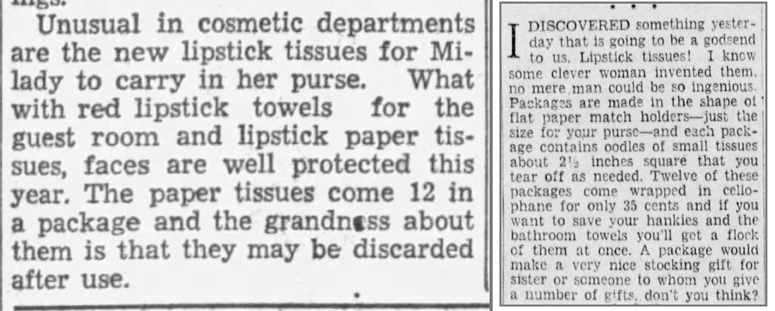

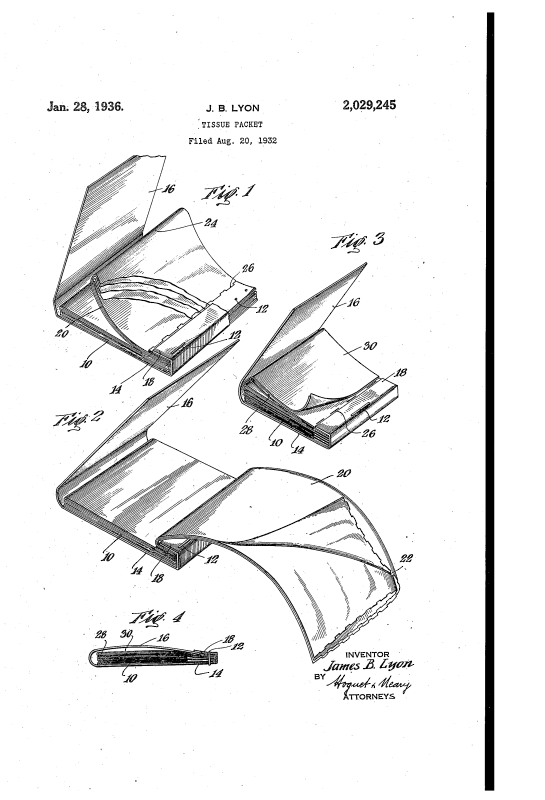

While they might have existed in the 1920s, I’m guessing lipstick tissues didn’t become mainstream until the early 30s, as this December 1932 clipping refers to them as new, while another columnist in December 1932 says she just recently discovered them (and they are so mind-blowing they were clearly invented by a woman, since “no mere man could be so ingenious”.)

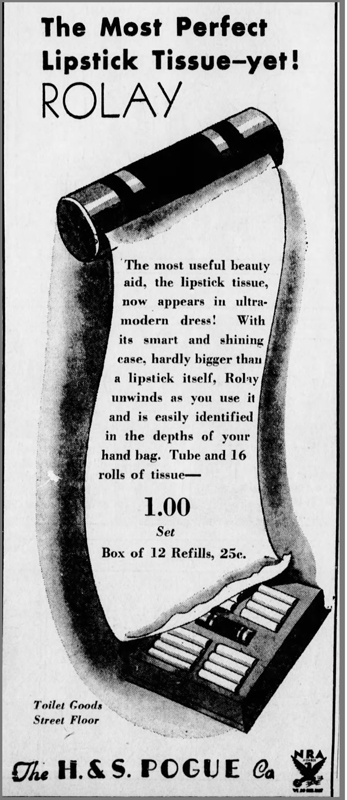

In addition to the tear-off, matchbook-like packages, lipstick tissues also came rolled in a slim case.

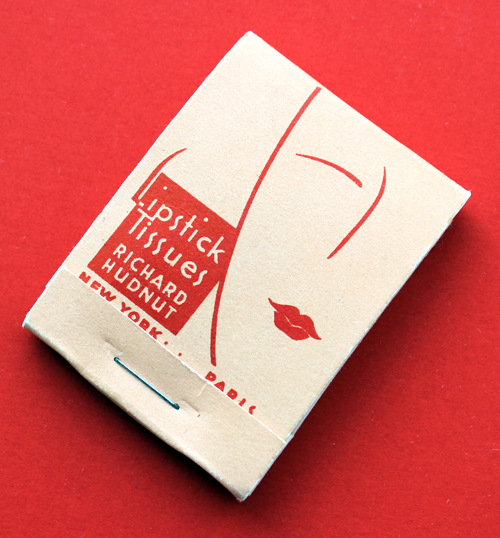

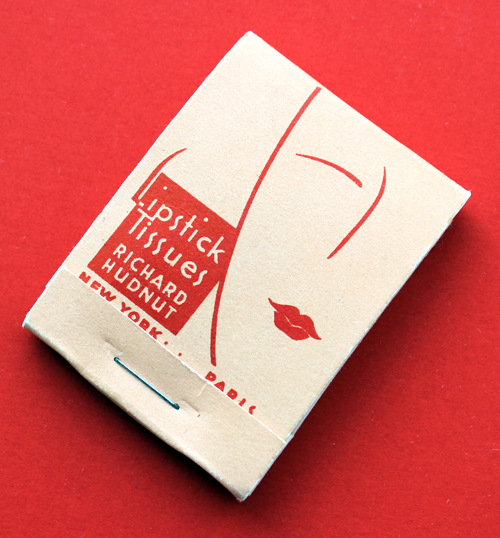

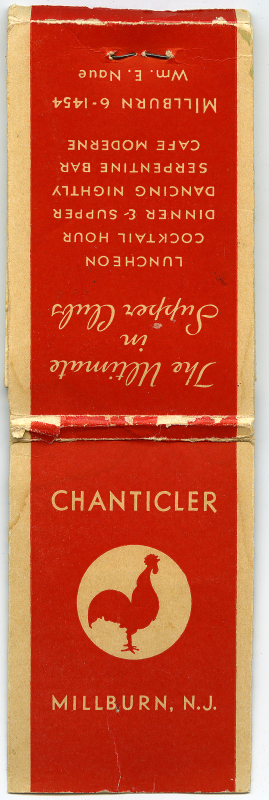

This lovely Art Deco design by Richard Hudnut debuted in 1932 and was in production at least up until 1934. I couldn’t resist buying it.

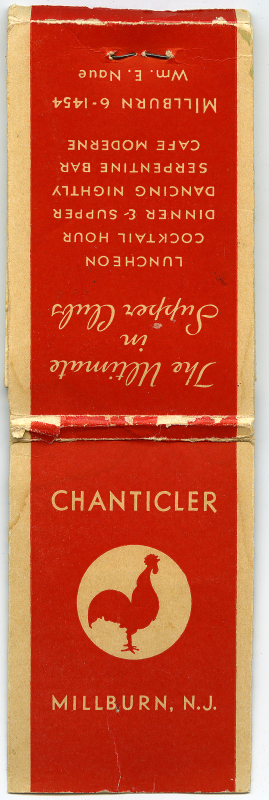

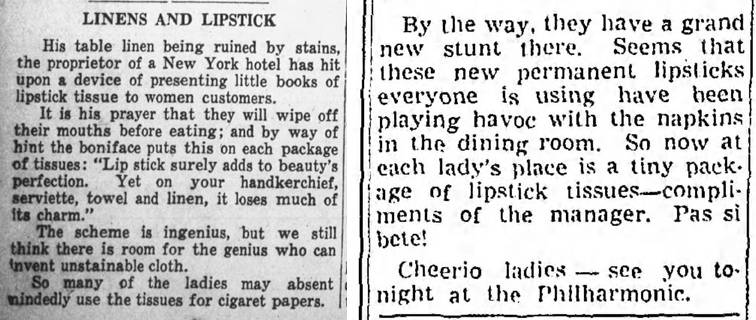

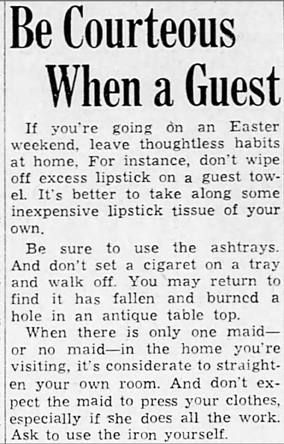

By 1935, restaurants and hotels had gotten wind of lipstick tissues’ practicality for their businesses, while beauty and etiquette columnists sang their praises. Indeed, using linens or towels to remove one’s lipstick was quickly becoming quite the social blunder by the late 30s.

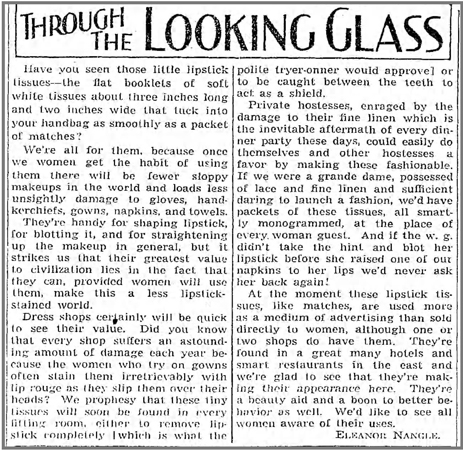

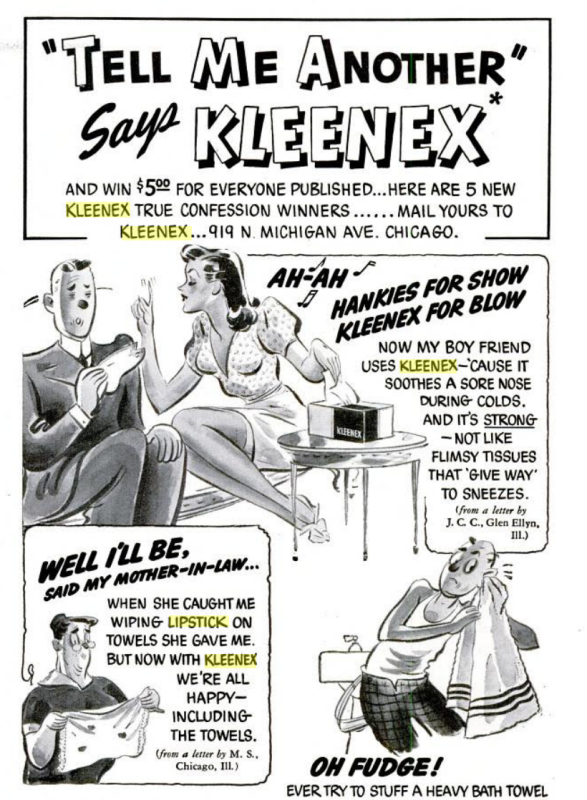

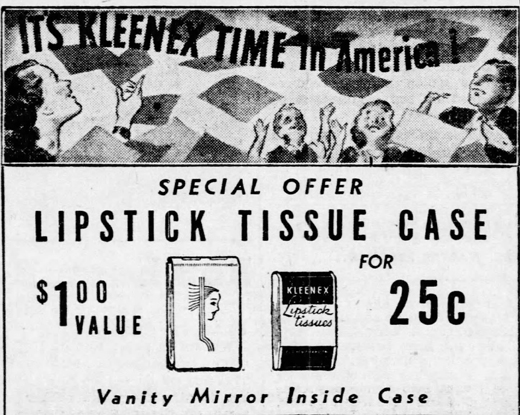

Kleenex was invented in 1924, but it wasn’t until 1937, when the company had the grand idea to insert tissues specifically for lipstick removal into a matchbook like package, that these little wonders really took off. You might remember these from my post on the Smithsonian’s collection of beauty and hygiene items. The warrior/huntress design was used throughout 1937 and 1938.

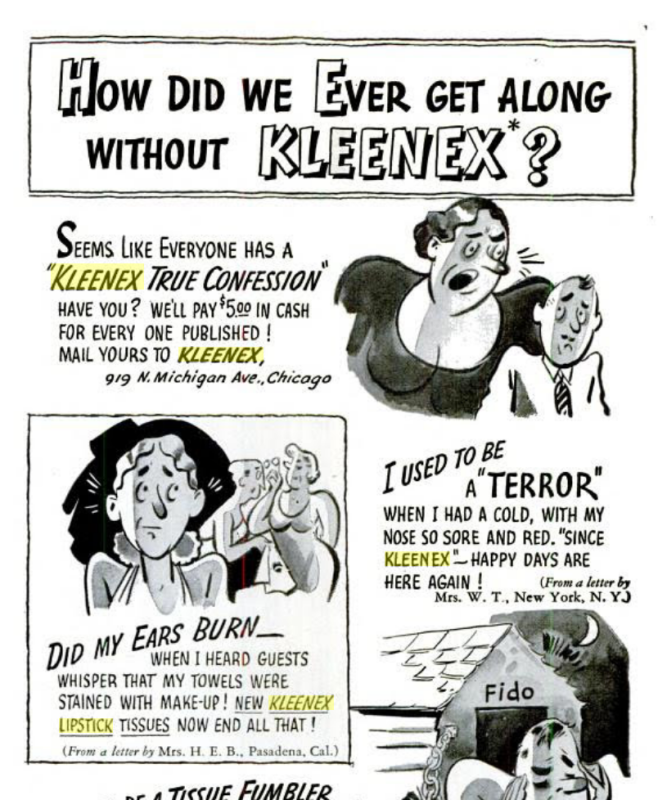

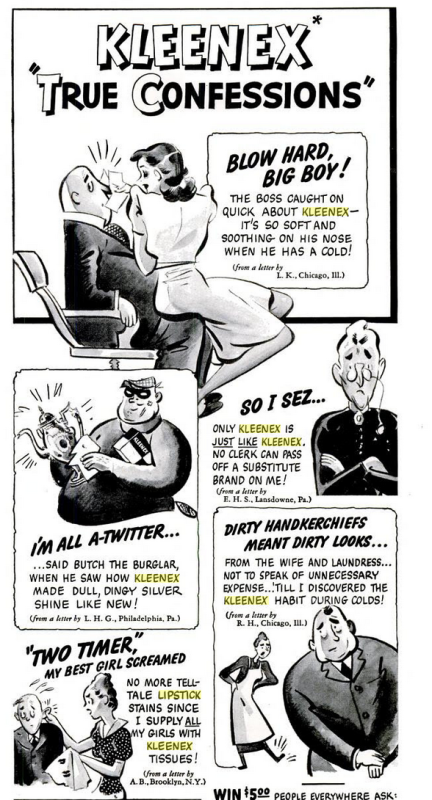

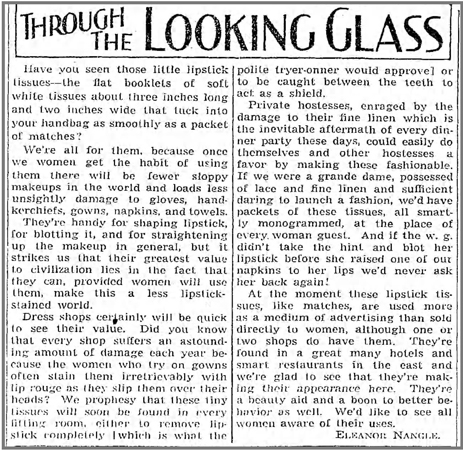

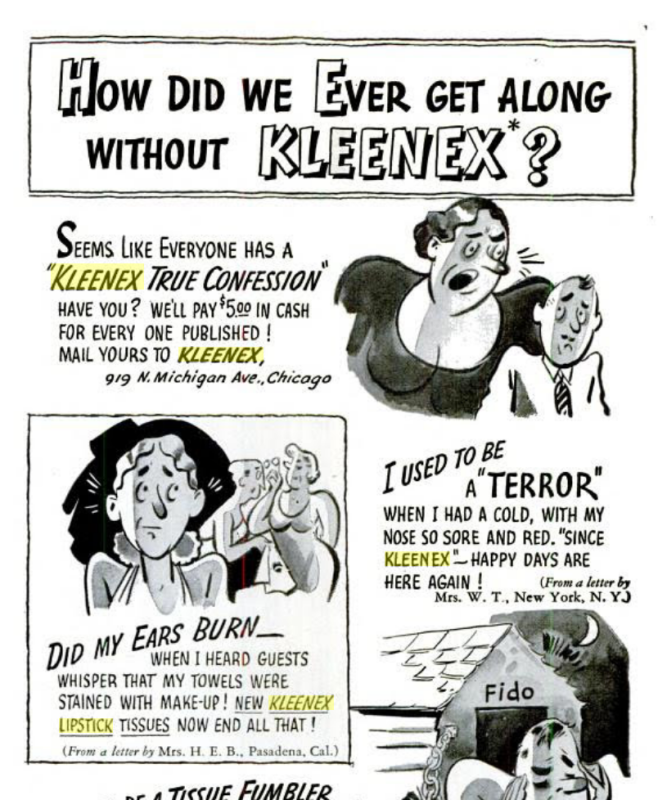

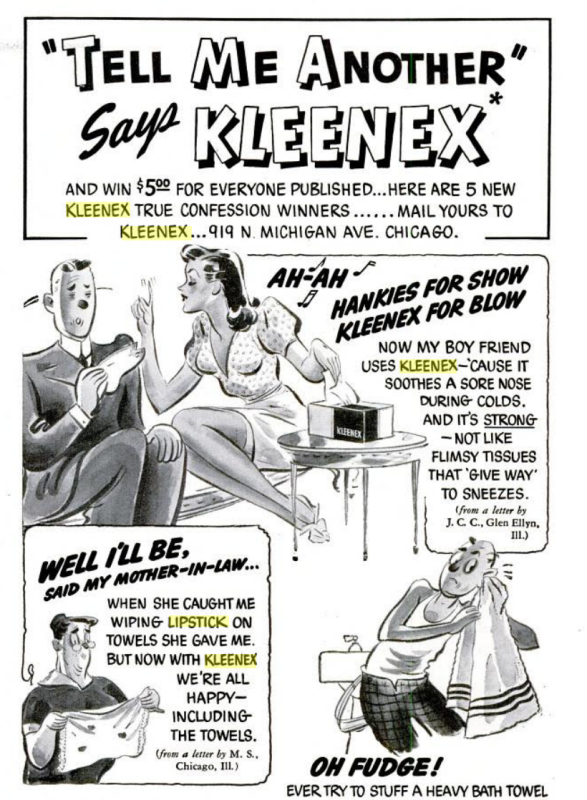

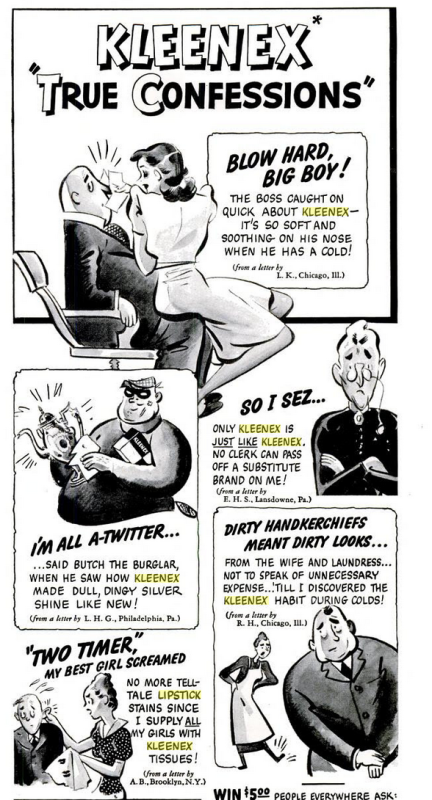

Kleenex started upping the ante by 1938, selling special cases for their lipstick tissues and launching campaigns like these “true confessions”, which appeared in Life magazine (and which I’m sure were neither true nor confessions.) With these ads, Kleenex built upon the existing notion that using towels/linens to remove lipstick was the ultimate etiquette faux pas, and one that could only be avoided by using their lipstick tissues.

These ads really gave the hard sell, making it seem as though one was clearly raised by wolves if they didn’t use lipstick tissues. Or any tissues, for that matter. Heaven forbid – you’ll be a social pariah!

Look, you can even use these tissues to cheat on your girlfriend! (insert eyeroll here)

(images from books.google.com)

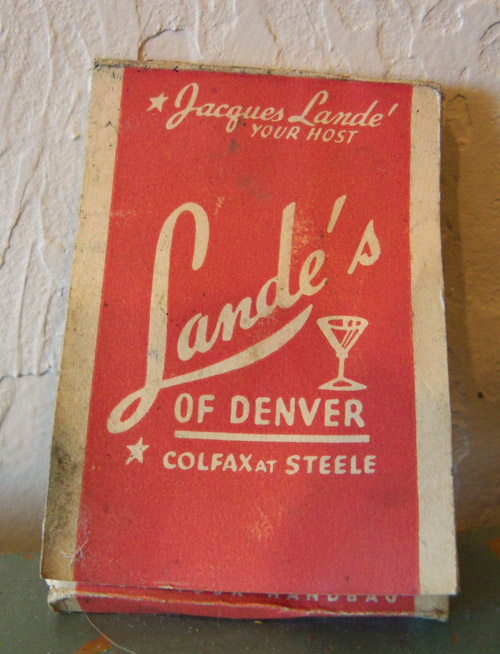

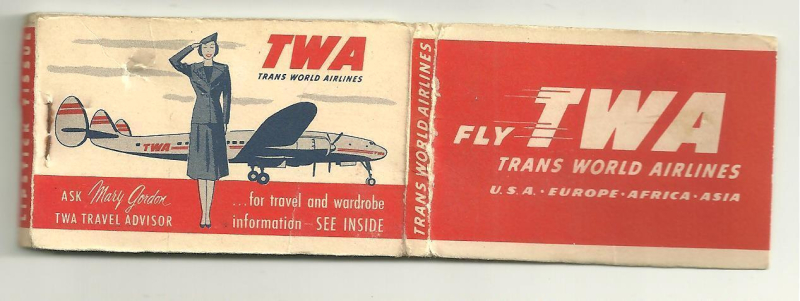

Not only that, Kleenex saw the opportunity to collaborate with a range of companies as a way to advertise both the companies’ own goods/services and the tissues themselves. By the early ’40s it was difficult to find a business that didn’t offer these gratis with purchase, or at least, according to this 1945 article, “national manufacturers of goods women buy.” And by 1946, it was predicted that women would be expecting free tissue packets to accompany most of their purchases.

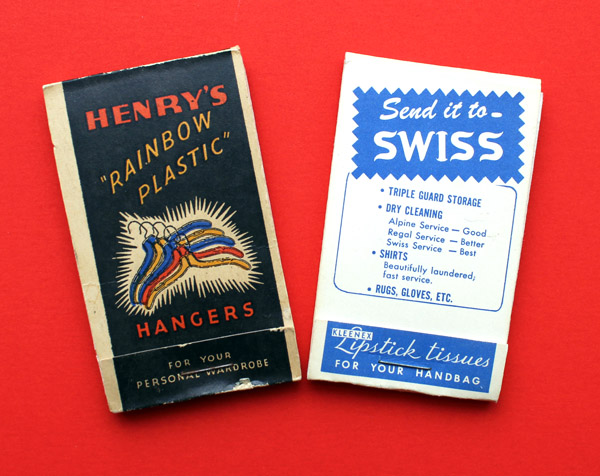

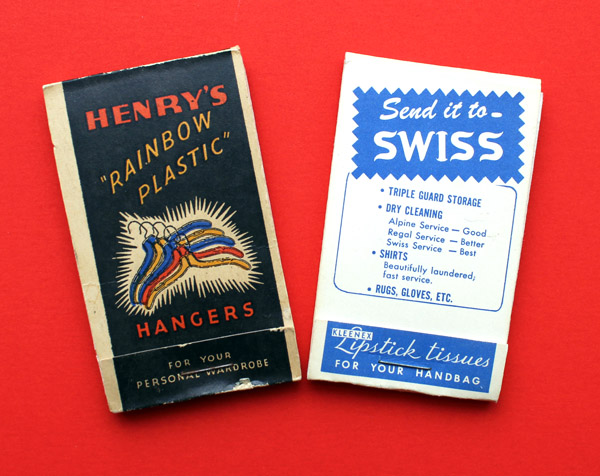

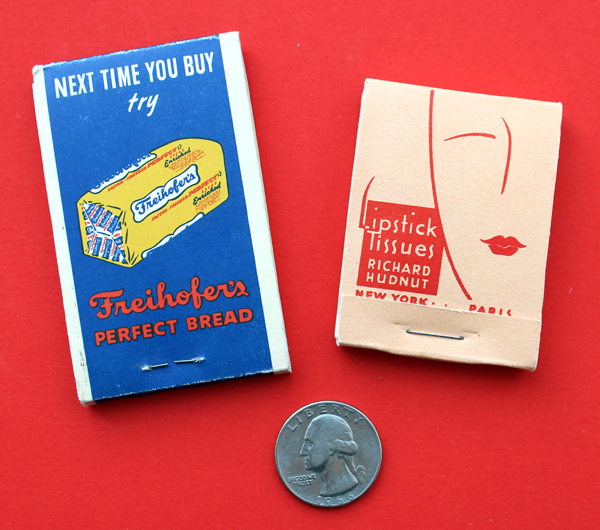

Needless to say, most of them consisted of food (lots of baked goods, since apparently women were tethered to their ovens), and other domestic-related items and services, like hosiery, hangers and dry cleaning.

(images from ebay.com)

(images from ebay.com)

(images from ebay and etsy.com)

(images from ebay and etsy.com)

(images from ebay.com)

(images from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

Naturally I had to buy a few of these examples for the Museum’s collection. Generally speaking, they’re pretty inexpensive and plentiful. The only one I shelled out more than $5 for was the Hudnut package since that one was a little more rare and in such excellent condition. Interestingly, these have a very different texture than what we know today as tissues. Using contemporary Kleenex to blot lipstick only results in getting little fuzzy bits stuck to your lips, but these vintage tissues have more of a blotting paper feel, perhaps just a touch thicker and ever so slightly less papery. It could be due to old age – paper’s texture definitely changes over time – but I think these were designed differently than regular tissues you’d use for a cold.

Anyway, Museum staff encouraged me to buy the cookie one. 😉

I took this picture so you could get a sense of the size. It seems the official Kleenex ones were a little bigger than their predecessors.

Wouldn’t it be cool to go to a restaurant and see one of these at the table? It would definitely make the experience seem more luxurious. I certainly wouldn’t feel pressure to use them for fear of committing a social sin, I just think it would be fun.

(image from etsy.com)

(image from mshhistoc.org)

I figured having a restaurant/hotel tissue packet would be a worthy addition to the Museum’s collection, since it’s another good representation of the types of businesses that offered them. I’d love to see a hotel offer these as free souvenirs.

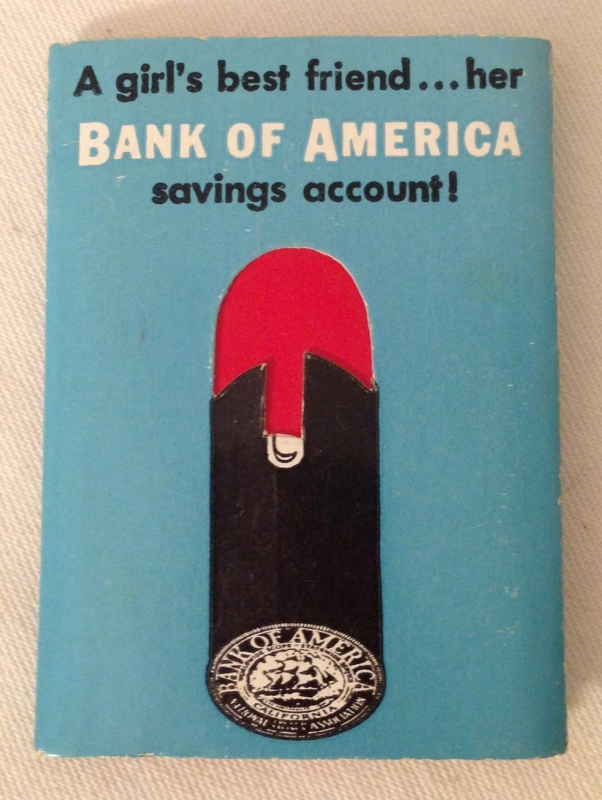

Here’s an example that doesn’t fit neatly into the baked goods/cleaning/hotel categories.

(image from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

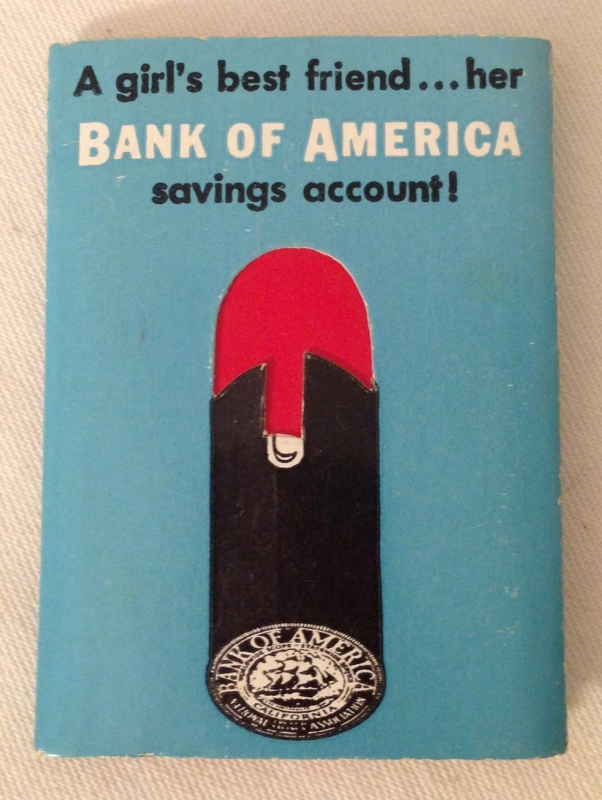

This one is also interesting. Encouraging women to be fiscally responsible is obviously more progressive than advertising dry cleaning and corn nut muffins, but it’s important to remember that at the time these were being offered by Bank of America (ca. 1963), a woman could have checking and savings accounts yet still was unable to take out a loan or credit card in her own name. One step forward, 5 steps back.

(image from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

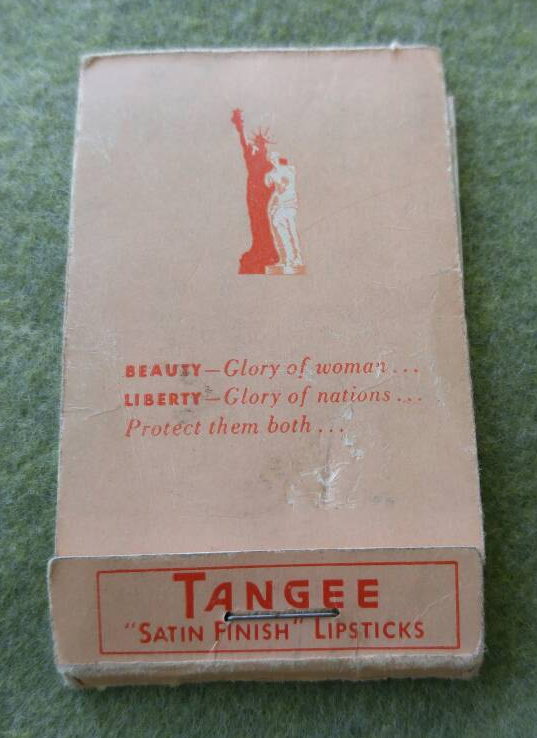

Of course, cosmetics companies also made their own lipstick tissues.

(image from etsy.com)

(image from etsy.com)

I was very close to buying these given how cute the graphics are, but didn’t want to spend $20. (I think they’re now reduced to $12.99, if you’d like to treat yourself.)

(image from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

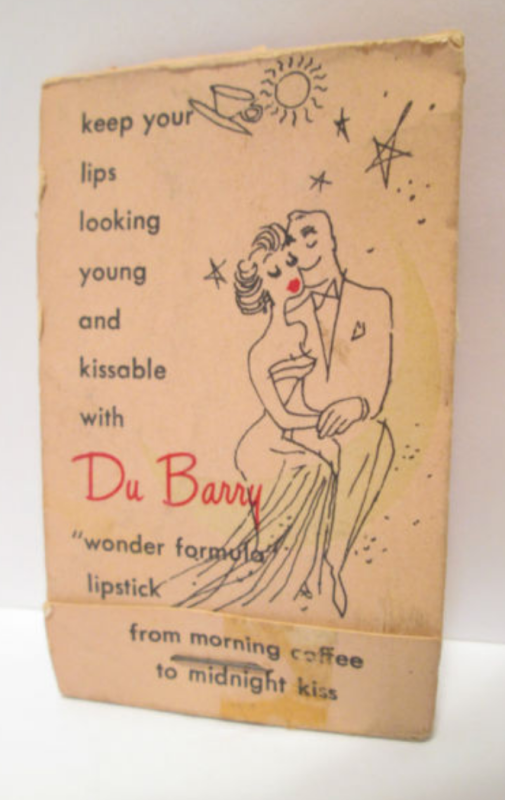

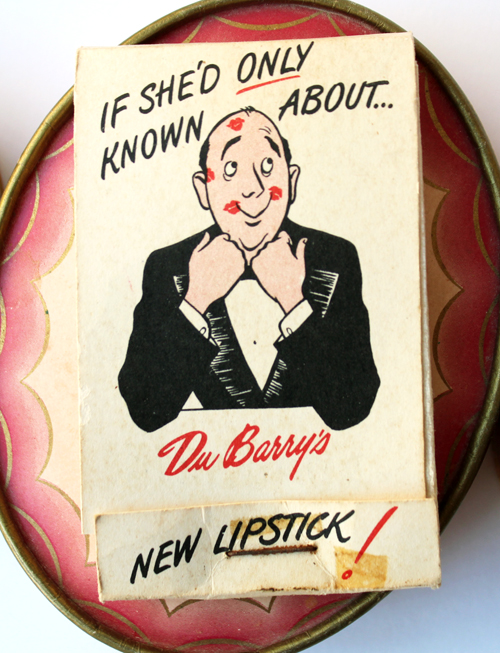

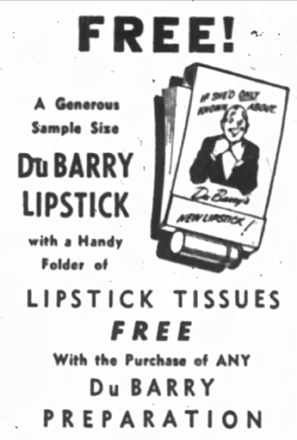

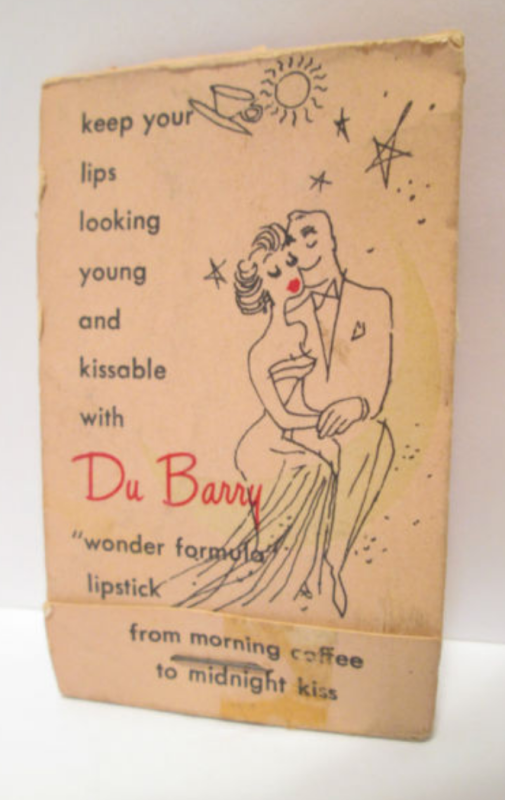

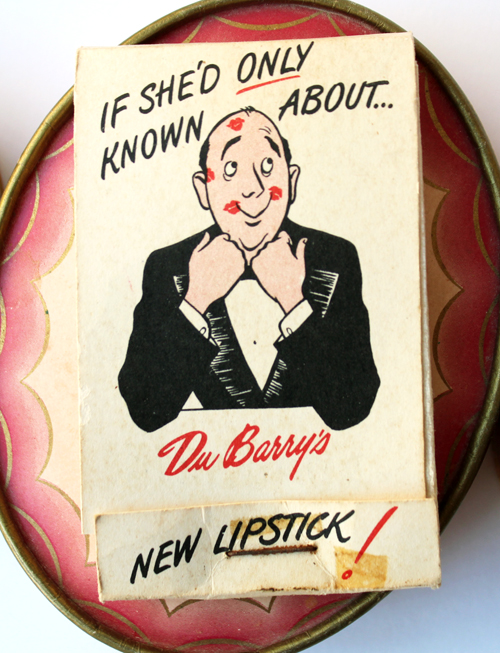

Plus, I already have these DuBarry tissues in the collection.

Funny side note: I actually found a newspaper ad for these very same tissues! It was dated July 27, 1948, which means the approximate dates I included in my DuBarry post were accurate.

By the late ’40s, lipstick tissues had transcended handbags and became popular favors for various social occasions, appearing at country club dinner tables to weddings and everything in between. I’m guessing this is due to the fact that custom colors and monogramming were now available to individual customers rather than being limited to businesses.

“Bride-elect”? Seriously?

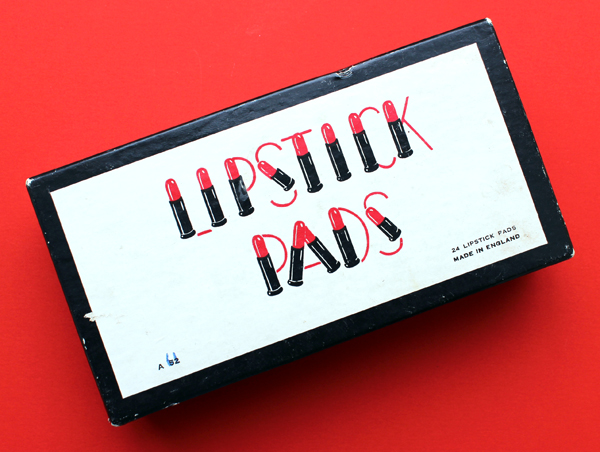

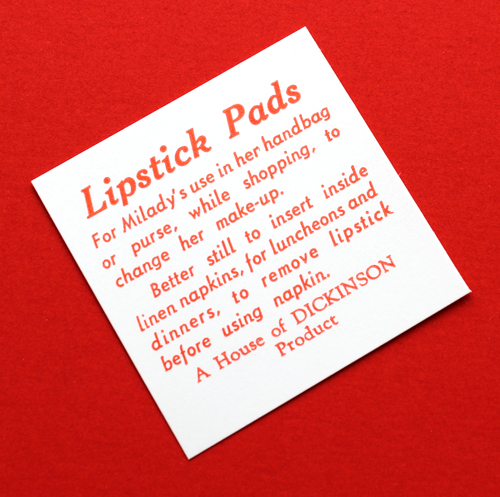

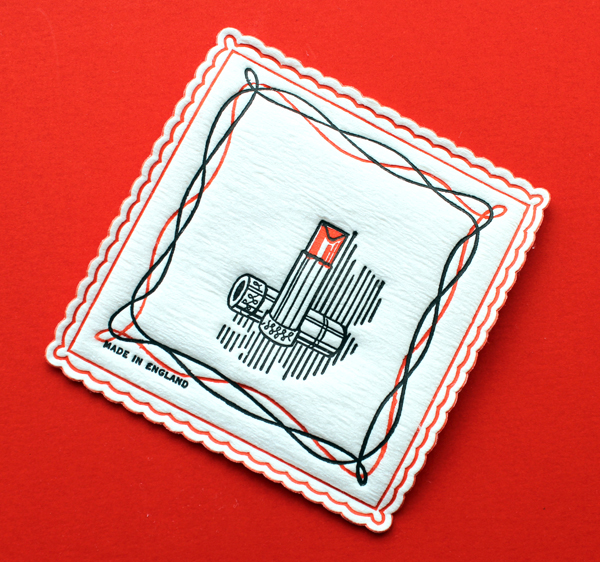

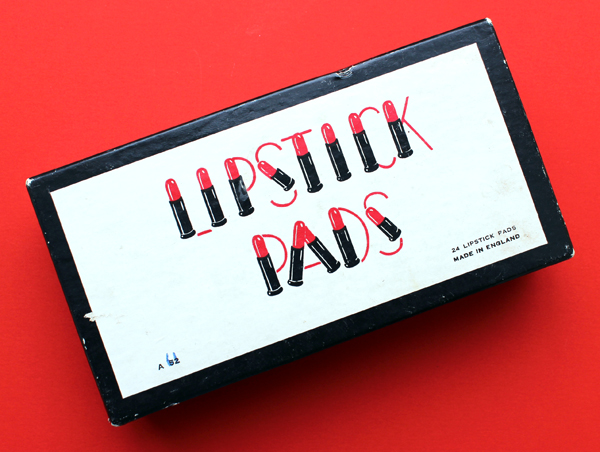

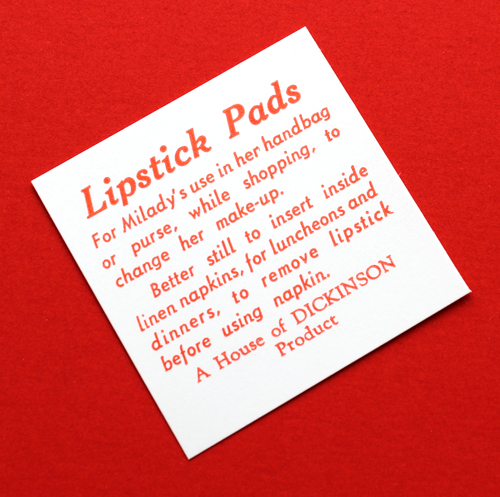

While the matchbook-sized lipstick tissues are certainly quaint, if you wanted something even fancier to remove your lipstick, lipstick pads were the way to go. These are much larger and thicker than Kleenex and came imprinted with lovely designs and sturdy outer box. This was the item that made me investigate lipstick tissues. I mean, look at those letters! I was powerless against their charm.

I couldn’t find anything on House of Dickinson, but boy did they make some luxe lipstick pads.

This design is so wonderful, I’d almost feel bad using these. If I were alive back then I’d probably go digging through my purse to find the standard Kleenex ones.

I also couldn’t really date these too well. There’s a nearly identical box by House of Dickinson on Ebay and the description for that dates them to the ’60s, which makes sense given the illustration of the woman’s face and the rounded lipstick bullet – both look early ’60s to my eye.

However, the use of “Milady” and the beveled shape of the lipstick bullet, both of which were more common in the ’30s and ’40s, make me think the ones I have are earlier.

By the mid-late ’60s, it seems lipstick tissues had gone out of favor. The latest reference I found in newspapers dates to November 1963, and incidentally, in cartoon form.

I’m not sure what caused lipstick tissues to fall by the wayside. It could be that there were more lightweight lipstick formulas on the market at that point, which may not have stained linens and towels as easily as their “indelible” predecessors – these lipsticks managed to easily transfer from the lips but still remained difficult to remove from cloth. Along those lines, the downfall of lipstick tissues could also be attributed to the rise of sheer, shiny lip glosses that didn’t leave much pigment behind.

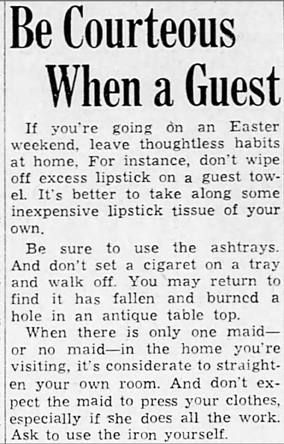

While these make the most sense, some deeper, more political and economic reasons may be considered as well. Perhaps lipstick tissues came to be viewed as too stuffy and hoity-toity for most and started to lose their appeal. My mother pointed out that lipstick tissues seemed to be a rich people’s (or at least, an upper-middle class) thing – the type of woman who needed to carry these in her handbag on the reg was clearly attending a lot of fancy soirees, posh restaurants and country club dinners. This priceless clipping from 1940 also hints at the idea of lipstick tissues as a sort of wealth indicator, what with the mention of antique table tops and maids.

Lipstick tissues were possibly directed mostly at older, well-to-do “ladies who lunch”, and a younger generation couldn’t afford to or simply wasn’t interested in engaging in such formal social practices as removing one’s lipstick on special tissues. Plus, I’m guessing the companies that used lipstick tissues to advertise labored under the impression that most women were able to stay home and not work. With a husband to provide financially, women could devote their full attention to the household so advertising bread recipes and dry cleaning made sense. This train of thought leads me, naturally, to feminism: as with the waning popularity of ornate lipstick holders, perhaps the liberated woman perceived lipstick tissues as too fussy – a working woman needed to pare down her beauty routine and maybe didn’t even wear lipstick at all. Lipstick tissues are objectively superfluous no matter what brainwashing Kleenex was attempting to achieve through their marketing, so streamlining one’s makeup regimen meant skipping items like lipstick tissues. Similarly, after reading Betty Friedan’s 1963 landmark feminist screed The Feminine Mystique, perhaps many women stopped buying lipstick tissues when they realized they had bigger fish to fry than worrying about ruining their linens. Then again, one could be concerned about women’s role in society AND be mindful of lipstick stains; the two aren’t mutually exclusive. And the beauty industry continued to flourish throughout feminism’s second wave and is still thriving today, lipstick tissues or not, so I guess feminism was not a key reason behind the end of the tissues’ reign. I really don’t have a good answer as to why lipstick tissues disappeared while equally needless beauty items stuck around or continue to be invented (looking at you, brush cleansers). And I’m not sure how extra lipstick tissues really are, as many makeup artists still recommend blotting one’s lipstick to remove any excess to help it last longer and prevent feathering or transferring to your teeth.

In any case, I kind of wish lipstick tissue booklets were still produced, especially if they came in pretty designs. Sure, makeup remover wipes get the job done, but they’re so…inelegant compared to what we’ve seen. One hack is to use regular facial blotting sheets, since texture-wise they’re better for blotting than tissues and some even have nice packaging, so they’re sort of comparable to old-school lipstick tissues. Still, there’s something very appealing about using a highly specific, if unnecessary cosmetics accessory. I’m not saying we should bring back advertising tie-ins to domestic chores or the social stigma attached to not “properly” removing one’s lipstick on tissues, but I do like the idea of sheets made just for blotting lipstick, solely for the enjoyment of it. I view it like I do scented setting sprays – while I don’t think they do much for my makeup’s longevity, there’s something very pleasing about something, like, say, MAC Fruity Juicy spray, which is coconut scented and comes in a bottle decorated with a cheerful tropical fruit arrangement. As I always say, it’s the little things. They might be frivolous and short-lived, but any makeup-related item that gives me even a little bit of joy is worth it. I could see a company like Lipstick Queen or Bite Beauty partnering with an artist to create interesting lipstick tissue packets. Indeed, this post has left me wondering why no companies are seizing on this opportunity for profit.

Should lipstick tissues be revived or should they stay in the past? Why do you think they’re not made anymore? Would you use them? I mean just for fun, of course – completely ignore the outdated notion that one is a boorish degenerate with no manners if they choose to wipe their lips on a towel, as those Kleenex ads would have you believe. 😉

Save

I remember thinking how cute and novel these wine bottle-shaped lipsticks were when they were making a sensation back in the fall. (I do have one on the way but the package somehow keeps getting delayed so here's a stock photo for now.) I'm not a wine person – gives me a horrible headache – but I do appreciate adorable makeup packaging so this gets a thumbs-up from me. I mean on the one hand I'm not fond of wine once again being associated with a clichéd feminine stereotype (all ladies love wine, shopping, chocolate and shoes, amirite?), but on the other hand, this lipstick is just too cute.

(image from beautyboxkorea.com)

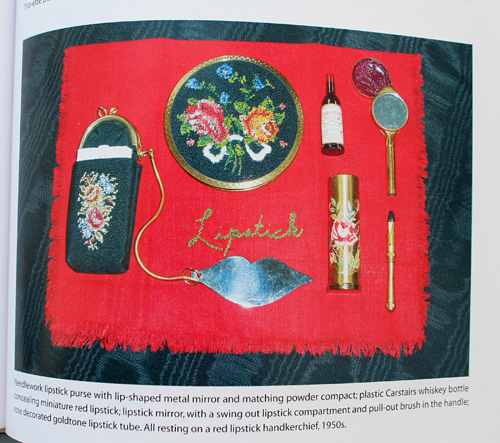

Turns out, this isn't the first time lipstick has been designed to resemble booze. I was positively tickled when, during one of my customary Friday night vintage makeup searches on Etsy (I lead a very exciting life, I know), I came across this miniature lipstick cleverly packaged as a whiskey bottle.

It really is mini!

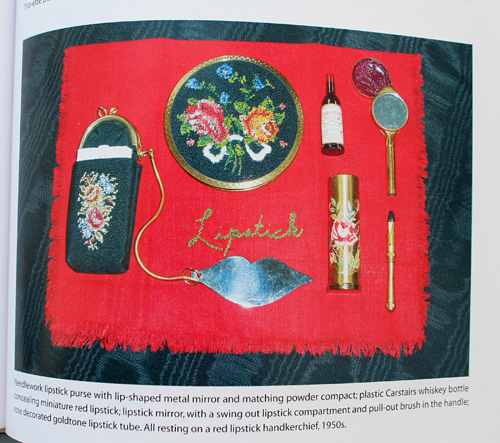

I'd never heard of Carstairs before, but apparently from roughly the '40s through the '60s they did a good amount of advertising for their White Seal whiskey, which is still sold today. In addition to the lipsticks, they offered mini screwdrivers and toothpicks, along with seal clock figurines and the usual print advertising. According to one (no longer active) ebay listing, the lipstick bottles started being produced around 1944 and other listings say they're from the '50s, so I guess they were used as promotional items for a few decades. Here's a photo of one in Madeleine Marsh's excellent book, which also dates it to the '50s.

I'm guessing that for the most part, the lipsticks were provided to bars and liquor stores and given away as a small gift-with-purchase, as there are quite a few full boxes of them floating around. I would have bought this one in a heartbeat because how cute would it have been to display it alongside a whole Chateau Labiotte set?

(images from etsy.com and labiotte.us)

(images from etsy.com and labiotte.us)

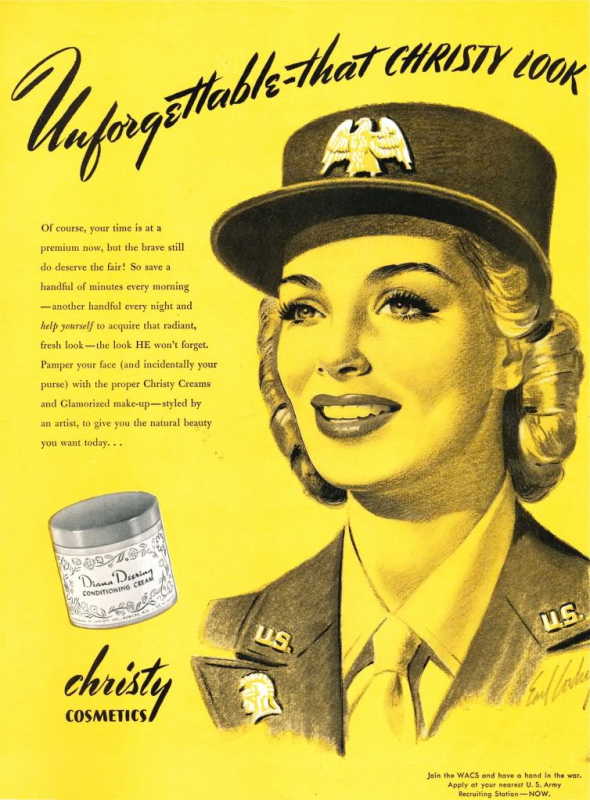

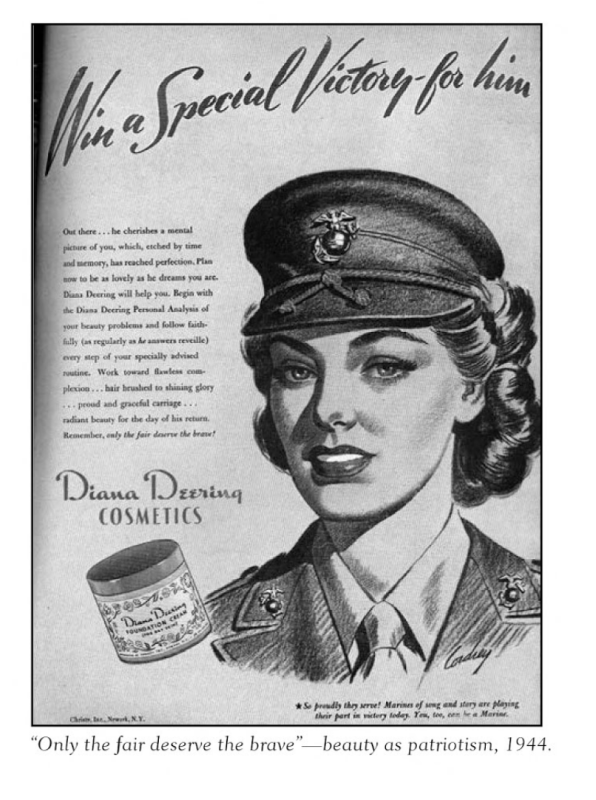

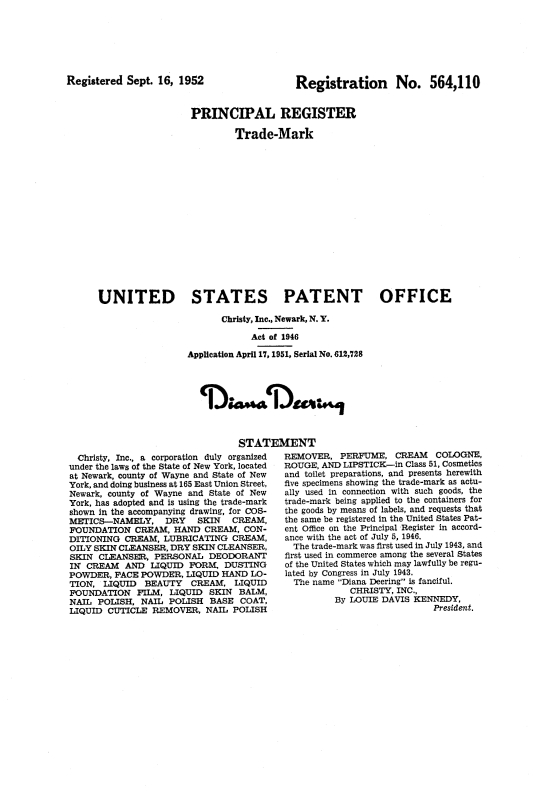

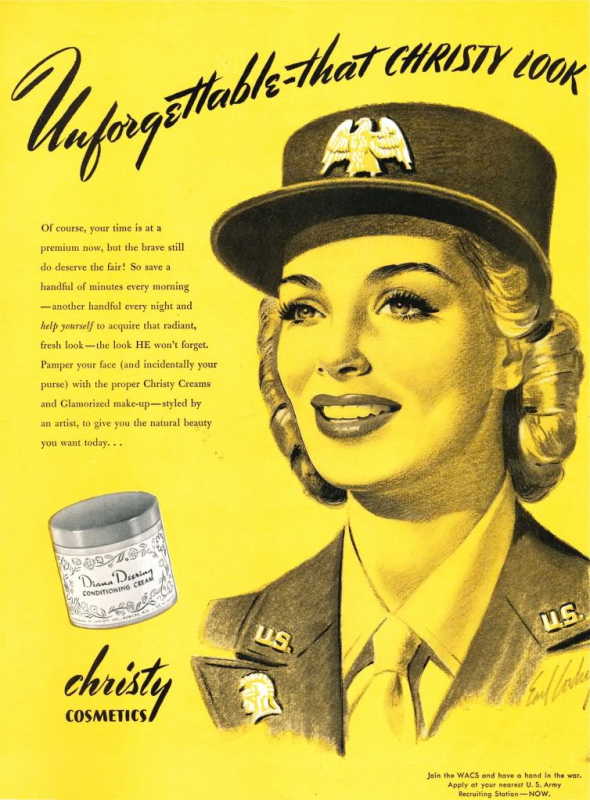

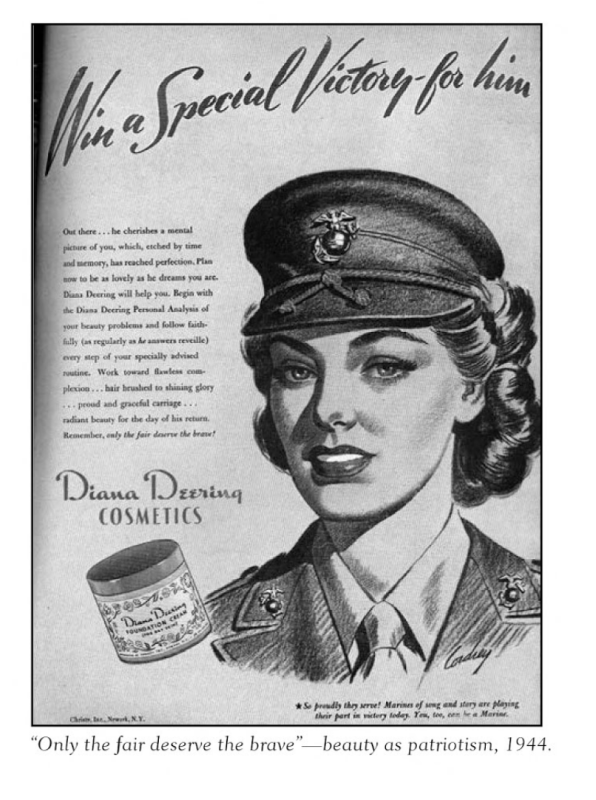

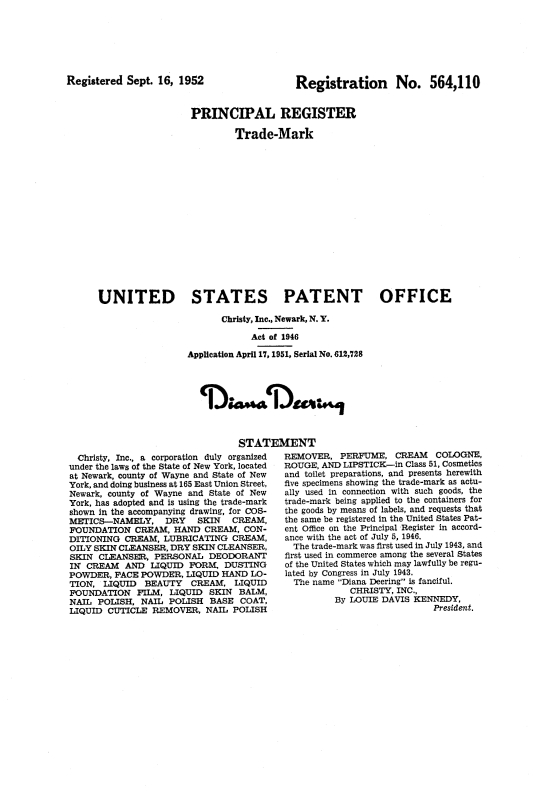

But the individual lipsticks are obviously a lot cheaper and I have many things I want to purchase for the summer exhibition, so I had to pass for now. ;) As for the lipstick itself, a company called Christy Cosmetics, Inc. was responsible for producing it. I couldn't find much information about it online, other than it was a New York-based company and was also the manufacturer of a line called Diana Deering (who was an entirely fictional character, or, as the patent puts it, "fanciful".)

(image from what-i-found.blogspot.com)

(image from what-i-found.blogspot.com)

(image from tsdrapi.uspto.gov)

(image from tsdrapi.uspto.gov)

I'm sure there's information about Christy out there somewhere, but as usual I lack the time and other resources to do proper research, i.e., looking beyond Google. If anyone knows anything about their relationship with Carstairs and how they were chosen to produce their promo items I'd love to hear it.

Uh-oh, we have a situation here. Once again a certain little Sailor is up to no good. "It's just my size!"

I better go get this wrapped up and into storage before he smears it all over his face in attempt to "drink" the non-existent whiskey. In any case, Happy St. Patrick's Day and I hope these lipsticks have inspired you to let your hair down and enjoy some adult beverages tonight!

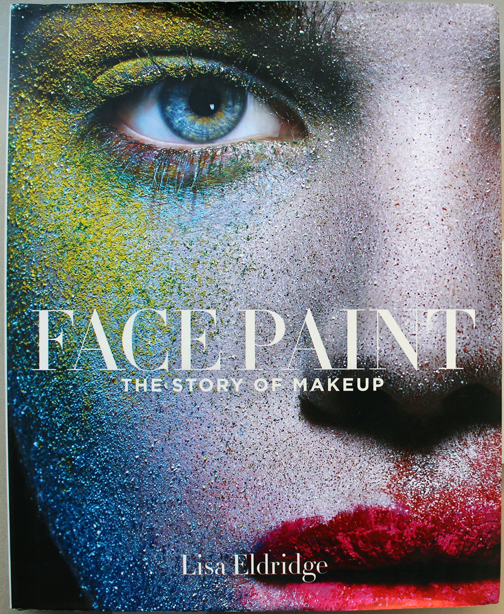

I had been salivating over this book since I found out the release date way back in the spring, and it did not disappoint. Celebrity makeup artist Lisa Eldridge published a broad yet fairly in-depth summary of cosmetic products and usage from ancient times to today.

Section 1 is divided into three sections detailing the history of the base colors historically used for cosmetics: red, white and black. Eldridge covers not only the ingredients used to make these pigments but also traces exactly how they were used in various eras, i.e. how rouged cheeks and lips, fair complexions and black eye liner were trending (or not) throughout history. Equally impressive is that these first two categories weren't simply a parroting of the information in Lips of Luxury, or the powder history in Ode to the Complexion (which I will get around to reviewing eventually.)

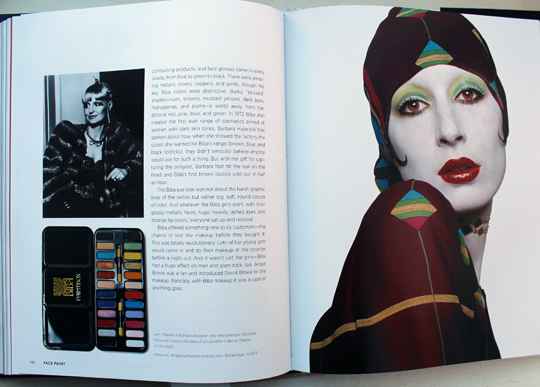

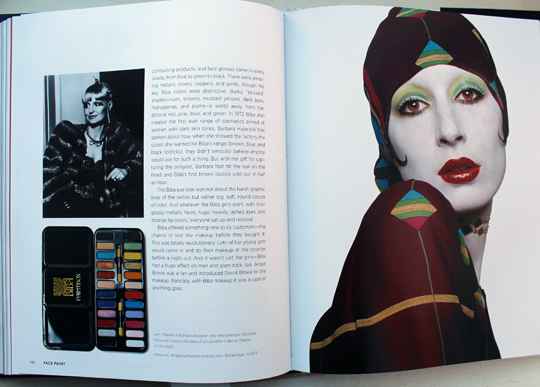

Section 2 focuses on all aspects of how the beauty industry developed into the one we know today, beginning with the evolution of cosmetics marketing and advertising. I know what you're thinking – this section probably started with the late 1800s/early 1900s, but you'd be wrong. Eldridge traces beauty marketing all the way back to the Renaissance, dissecting how the messages contained in beauty advertising changed over time. The second part of this section discusses the big beauty company founders like Max Factor, Helena Rubinstein, and Elizabeth Arden. But there were some unexpected bios of the women who began more indie lines, like Mary Quant and Barbara Hulanicki, who started Biba.

The third part of Section 2 deals with the rise of our basic products – mascara, lipstick, eye shadow, blush, foundation/powder, bronzer and nail polish – along with the companies that pioneered these items. I liked how Eldridge came up with a logical arrangement of these brands into overarching categories: couture houses, perfume companies, drugstore mainstays and makeup artists.

Could you imagine having this on your vanity?

Section 2 ends with what lies ahead for makeup in terms of technological advances, while the afterword is a brief but meaningful analysis of the significance of wearing (or not wearing) makeup nowadays. I like the last line: "Ultimately, nothing empowers a woman more than the right to a good education, and the freedom to choose whether to wear a red lip and smoky eye…or not."

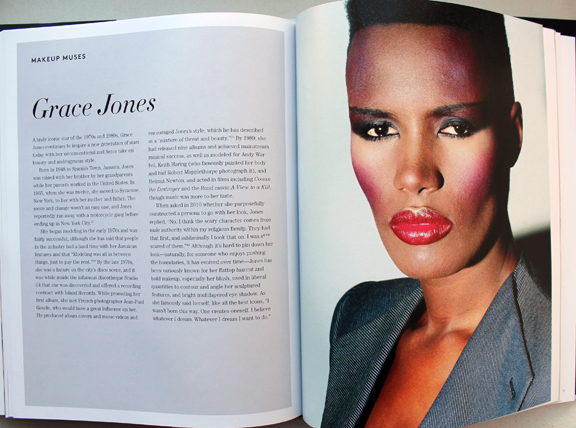

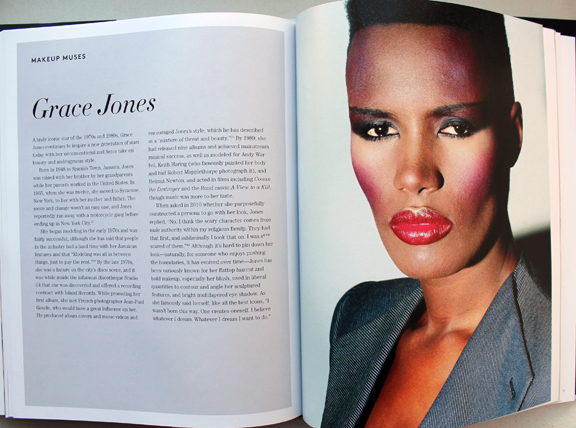

The whole book is sprinkled with profiles of Eldridge's "makeup muses," women who are associated with particular beauty looks that continue to inspire makeup artists today.

There are also some really cool avant-garde looks throughout…I just wish I knew whether Eldridge herself created them. I'm assuming she did.

I loved the back cover too – doesn't this picture just make you want to dive into a pile of makeup?!

Relating a global history of makeup is a daunting task, and Eldridge did it well. This is not your standard makeup history book as it provides an in-depth look at not just the industry and cosmetic products but also their applications throughout history. Now, I love me some coffee table books with pretty pictures of beautiful makeup and hope to publish my own someday. I adore books that are basically eye candy and provide scant information on the objects. And obviously one of the main goals of the Makeup Museum is to show that beauty objects themselves can be art or cultural artifacts and that their meaning goes beyond their basic utilitarian purpose. But what I liked about Face Paint is that it got me out of my usual way of thinking about makeup mostly as art/cultural object. That's all well and good, but it's important to also reflect on makeup's roots, i.e. why it was invented in the first place. Face Paint was a great reminder for me to consider not just the design or cultural significance of a makeup object but how it's used, and hopefully I will keep this in mind going forward with various books and exhibitions. This aspect of Face Paint has the added bonus of appealing to a wide market - it's a gem for makeup collectors and non-collectors alike. Also, if anyone is going to discuss makeup application throughout the years, it's Eldridge. She has the same appreciation I do for package design, but also the perspective of a world-famous makeup artist who has spent countless hours actually applying it on thousands of people.

Will you be buying Face Paint, either for yourself or for that special makeup aficionado in your life? If you do treat yourself, be sure to check out the sources at the end. I know I've added several books to my wishlist!

I can't even remember what I was researching when I stumbled across this site chock full of vintage compacts, but I'm so glad I did. I was dazzled by both the quantity and quality of this person's collection, and then I saw that it formed an exhibition that took place a decade ago. "The Art of Allure: Powder Compacts and Vanities of the 19th, 20th and 21st Centuries" was on display at the University of Arizona Museum of Art in April and May of 2004, so at this point it's a vintage exhibition of vintage compacts.

I can't even remember what I was researching when I stumbled across this site chock full of vintage compacts, but I'm so glad I did. I was dazzled by both the quantity and quality of this person's collection, and then I saw that it formed an exhibition that took place a decade ago. "The Art of Allure: Powder Compacts and Vanities of the 19th, 20th and 21st Centuries" was on display at the University of Arizona Museum of Art in April and May of 2004, so at this point it's a vintage exhibition of vintage compacts.

The collector behind this wonderful compilation is Noelle Soren, whose bio I pored over and have decided it's movie-worthy. She and her husband both hold advanced degrees in archaeology and art history (ahem) and have traveled the world digging up various artifacts. Eventually she found her way to collecting vintage compacts, and she also wrote and photographed the catalogue for the exhibition. The catalogue is available online and is incredibly informative. She also mentioned that hard copies of the catalogue do appear on Ebay from time to time, so I'm going to keep my eyes peeled in the hopes of snagging one. Definitely check it out (but only if you have plenty of time – you can easily spend an hour looking at everything!)