It's the most wonderful time of the year…to look at vintage Christmas makeup ads, that is! You know I can't get enough of these, so here's a quick roundup (in no particular order) of some I added to the Museum's collection this year. 🙂

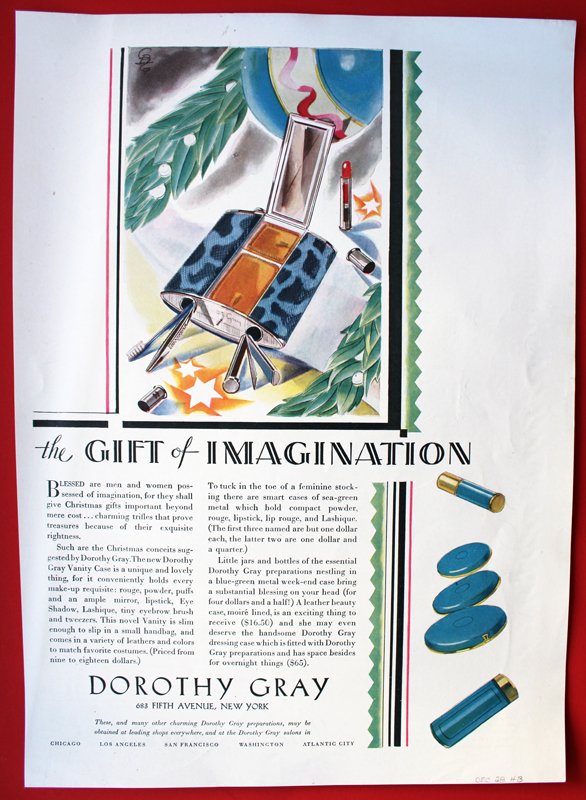

I have many Dorothy Gray ads, but not any from the '20s. Their early packaging was so sleek.

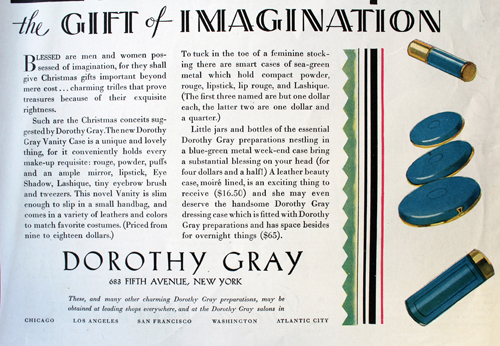

Apparently you can avoid an inferiority complex with a manicure set. LOL.

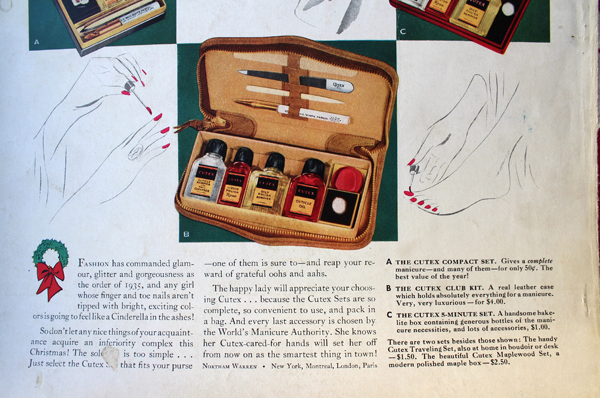

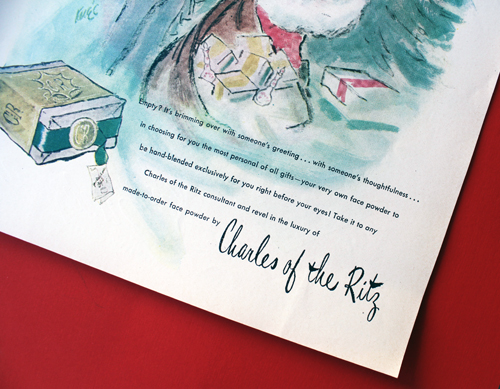

Santa, you jerk! Why did you give me an empty box? Now I have to go to the store and have it filled?! That's not a good present!

I understand custom powder was Charles of the Ritz's bread and butter and you had to actually go to a counter to get your own personal blend, but I'd still be pissed if someone gave me this. Get me a nice compact!

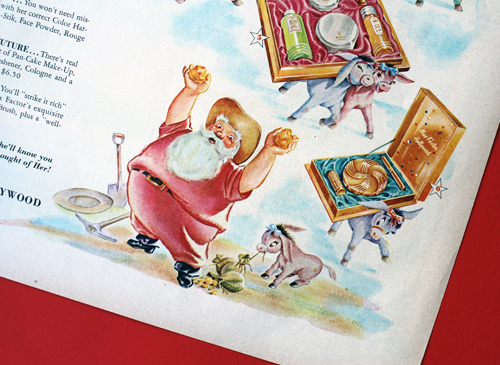

Santa gave considerably better gifts in this ad. I'm a bit confused about the presence of donkeys (shouldn't it be reindeer?), but I do love the overall cartoon-y look of this one.

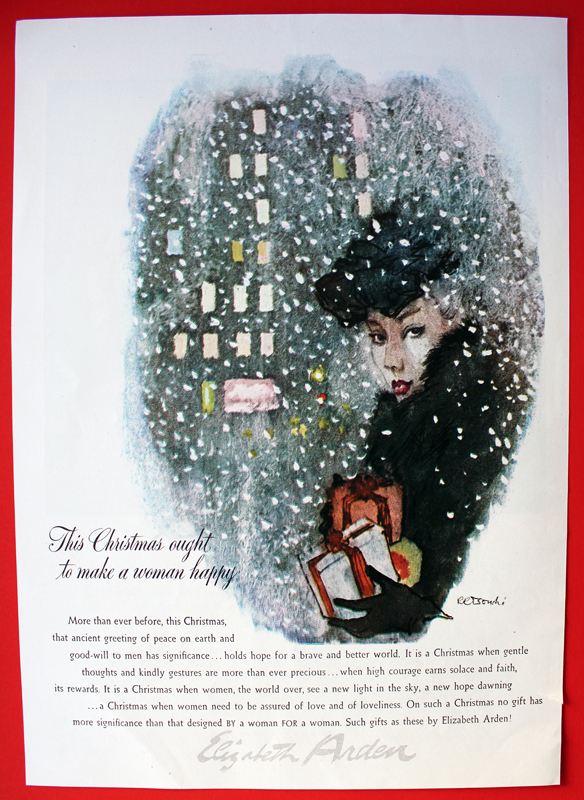

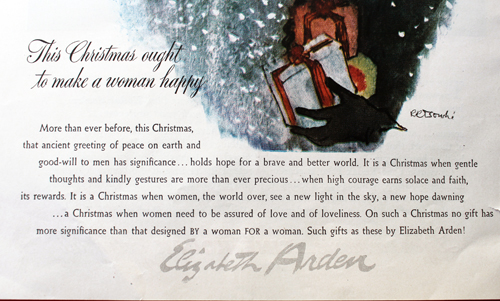

René Bouché (1905-1963) was Elizabeth Arden's head advertising illustrator in addition to working for Vogue. If you see an illustrated ad for Elizabeth Arden from the 40s or 50s most likely it was done by Bouché's hand. I believe this is the first ad by this artist to join the Museum's collection. 🙂

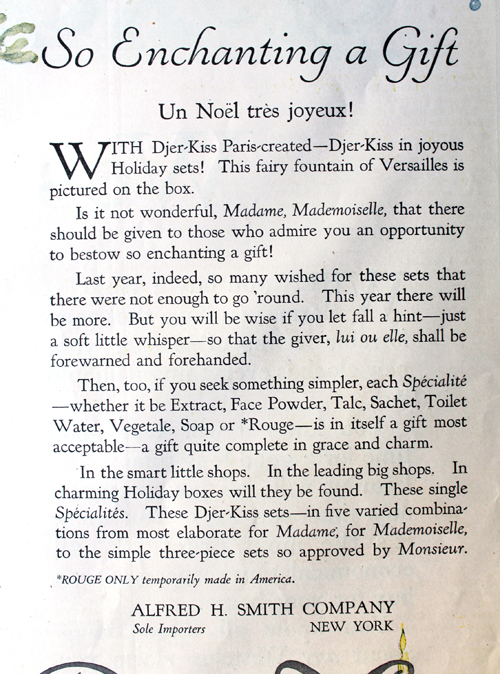

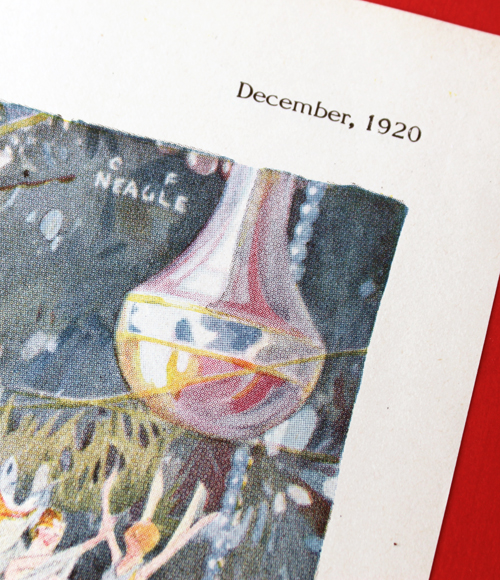

I can't recall how I stumbled across these Djer-Kiss ads, but I'm so pleased I found them! Djer-Kiss "Kissing Fairies" compact has been on my wishlist for a long time, but the ads are just as gorgeous as the compacts. I'm hell-bent on collecting all of them, as they're simply beautiful and feature a variety of illustrators. Collecting Vintage Compacts has an amazingly thorough history of the company, which makes me want them all the more. I believe the illustrator for this one was Willy Pogany, although I couldn't find a signature anywhere so I can't be sure.

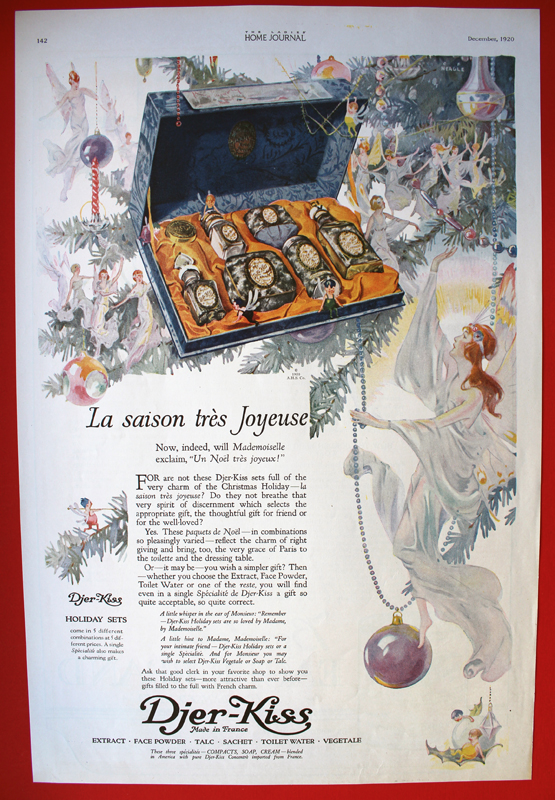

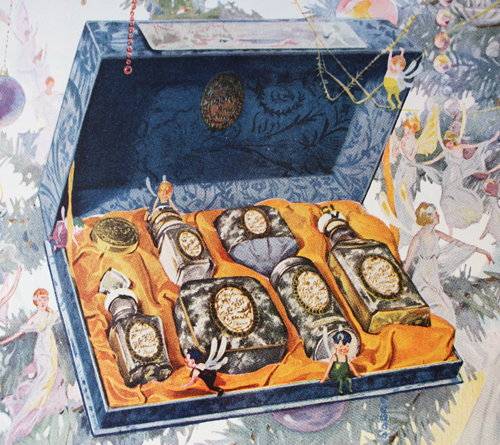

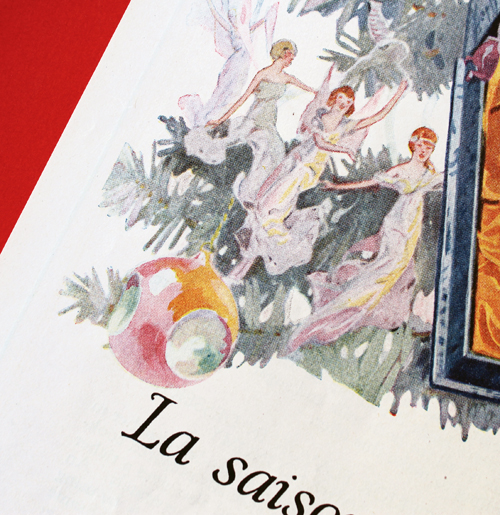

This one is by C.F. Neagle, who does a breathtaking job of capturing iridescence – from fairy wings to Christmas baubles, there's a multi-colored sheen that seems to pop off the page.

I love all the little sprites flitting about the gift box, particularly the ones hanging off the top and sitting on the edge. Incredibly charming, no?

So that concludes 2017's vintage Christmas ad roundup! Which one was your favorite? I love all of these, of course, but I'm partial to the very silly Max Factor ad and the beautiful Djer-Kiss ads.