I am forever grateful for those who approach me with makeup they no longer want or that they feel belongs in the Museum. While 2020 was another hellish year for me personally and the Museum, as well as basically the whole world, I believe a record number of donations were received. Here’s a brief overview of what was graciously bestowed upon the Museum this year.

First up is a mint condition Max Factor gift set. A very nice woman in Canada donated it, noting that it was a birthday present from her father to her mother one year. According to newspaper ads it dates to about 1948. I love the suggested use for the box lids as “party trays”!

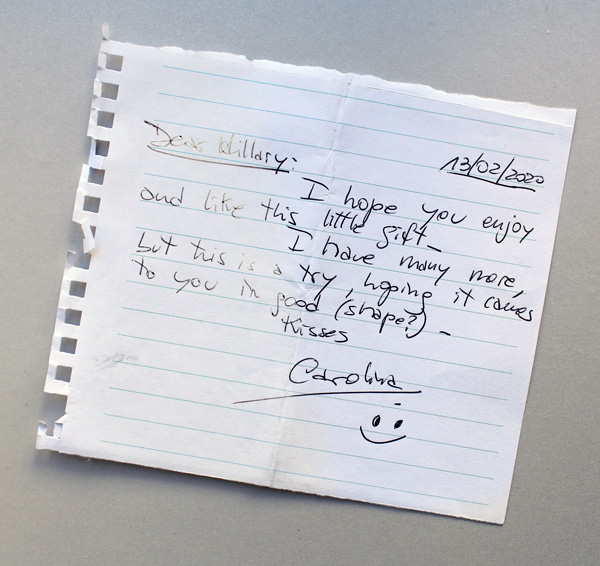

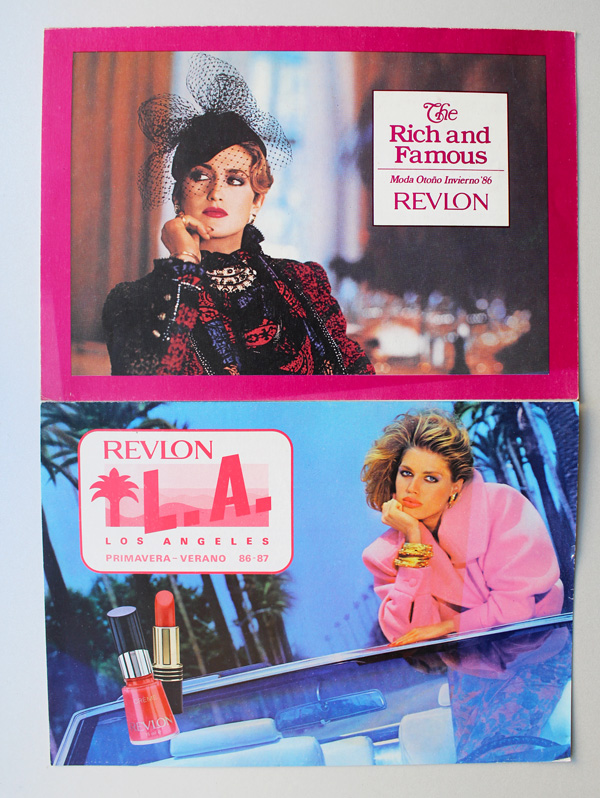

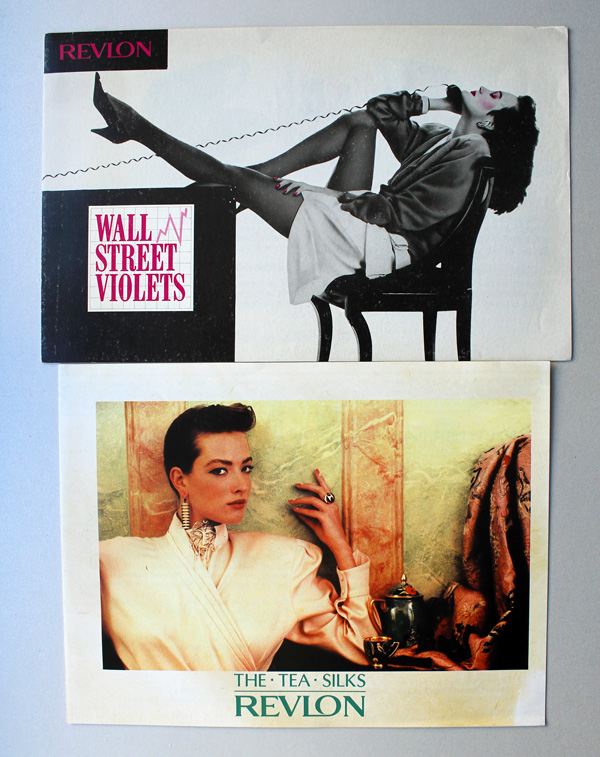

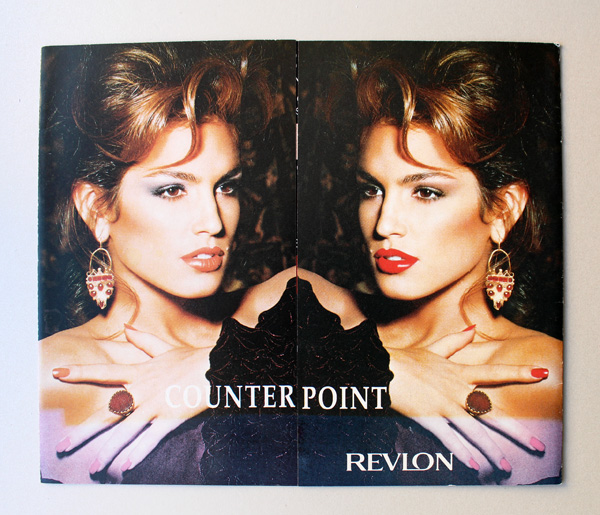

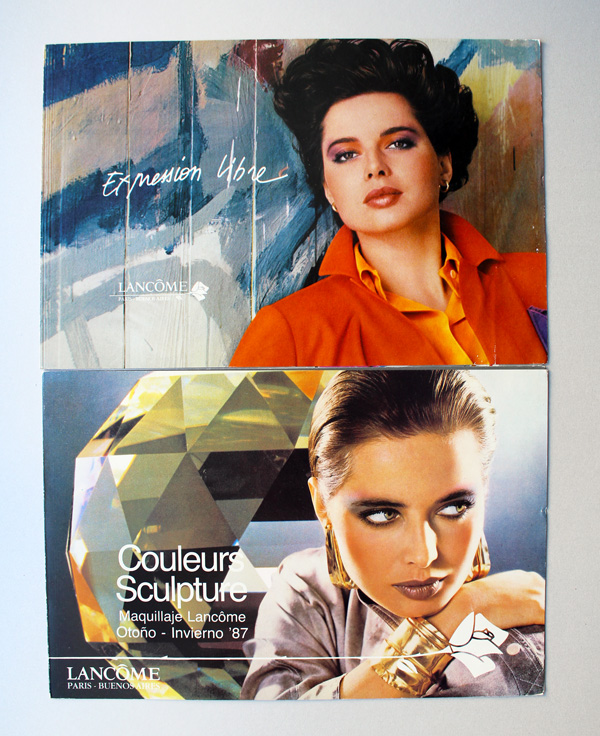

Next up is a slew of awesome ads and postcards from the ’80s and ’90s, donated by an Instagram buddy from Argentina. Such a sweet note too!

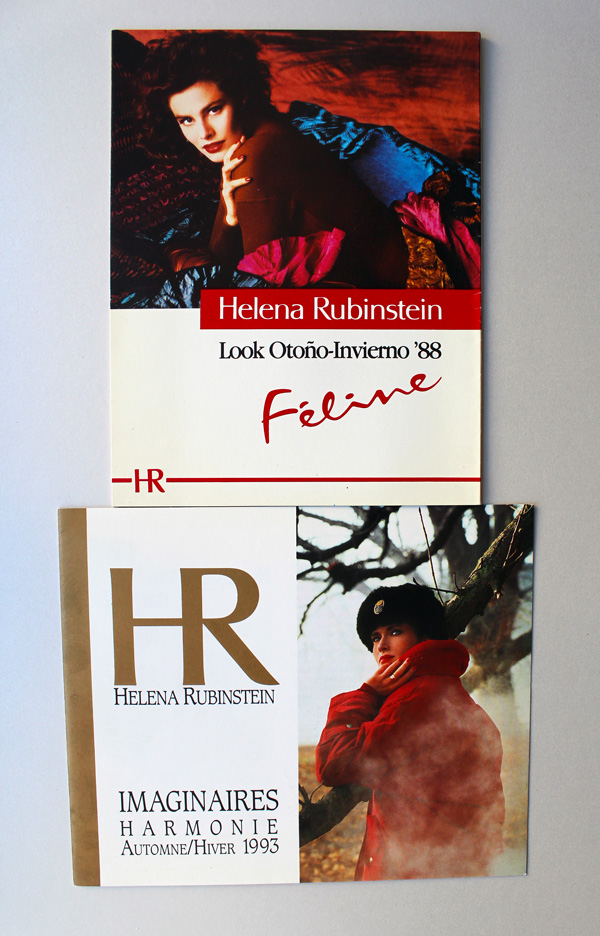

This next one is super interesting. Normally the Museum does not include hair products, but the donor is a fellow collector and very knowledgeable about Russian culture, having lived in Moscow for several years. This vintage hair dye was made in East Germany and exported to the USSR.

Next up are some lovely Elizabeth Arden objects. These were donated by a woman in California whose mother worked at the Elizabeth Arden counter at a department store. Here we have the Napoleonic compact which was introduced around 1953, Faint Blush, the famous Ardena patter, and some Color Veil (powder blush) refills.

Near as I can figure, the Faint Blush was a sort of foundation primer, but it seems like it could also be worn alone. I love the plastic pink rose packaging, as it’s very much of its era (ca. 1963-1973). I think the patter and the Faint Blush are my favorites from this bunch.

Then, another very kind Instagram friend and fellow collector sent a huge lot of vintage powder boxes and compacts. The Museum did not have any of these…some I hadn’t even heard of and some I had only admired them from afar. I just about died when I opened the package! Clockwise from top left: a 1930s eyeshadow by a company called Quinlan, a 1920s Harriet Hubbard Ayer Luxuria face powder, a powder dispenser by Cameo (probably from around the ’30s), a ’20s Marcelle compact tin, an extremely rare Red Feather Rouge tin (ca. 1919), an unmarked lipstick and floral powder tin, a Princess Pat compact from about 1925, a Yardley English Lavender tin (ca. 1930s) and a Fleur de Glorie face powder compact (ca. 1923-1926). In the middle is an amazing pink plastic 1940s Mountain Heather face powder case, a line manufactured by Daggett and Ramsdell.

I love each and every piece, but my favorites are the eyeshadow compact, and an adorable Mondaine book compact (with the original box!) that was also included. Bookworm that I am, I want a whole “library” of these designs.

Not all of the donations were vintage. I was so happy to have received these two nail polishes from another IG friend. They were the result of a 2016 collaboration between Cirque Colors and the Met in honor of the latter’s Manus x Machina exhibition.

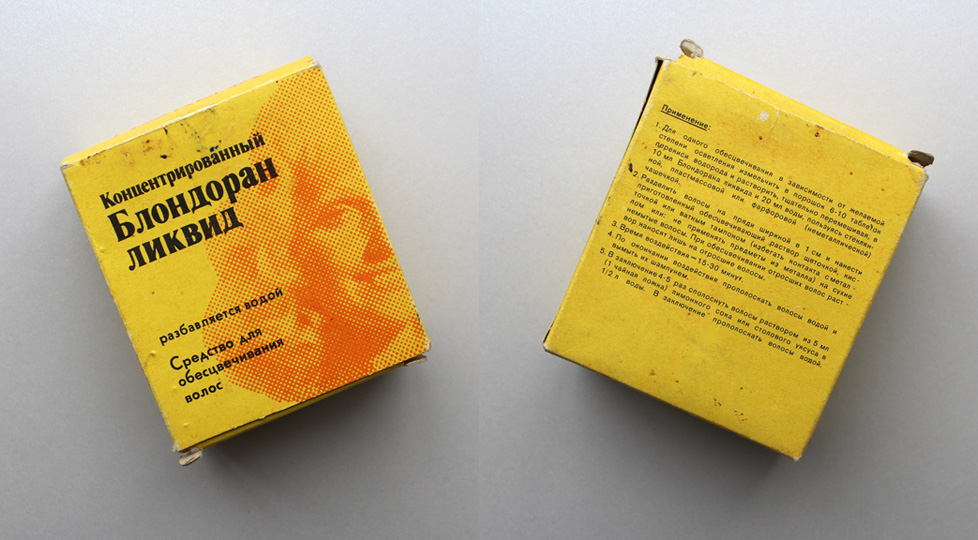

I’m sure you remember the kindness of makeup artist Amelia Durazzo-Cintron, who shared her memories of working for Kevyn Aucoin back in July. For some reason she felt the need to thank ME instead, and did so by donating a really cool Black Swan makeup kit. How nice is her note?!

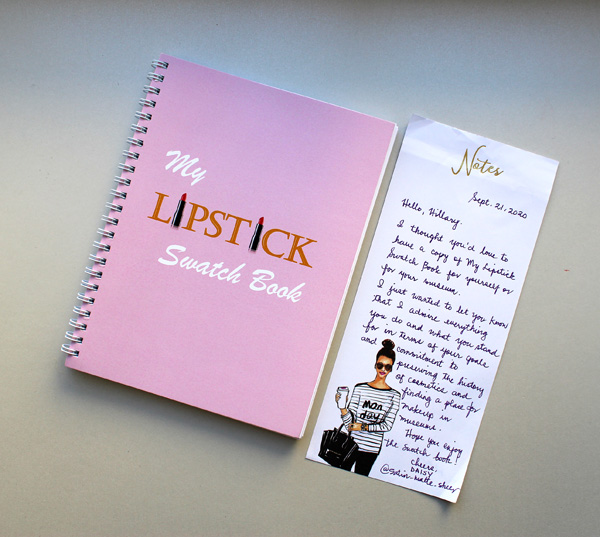

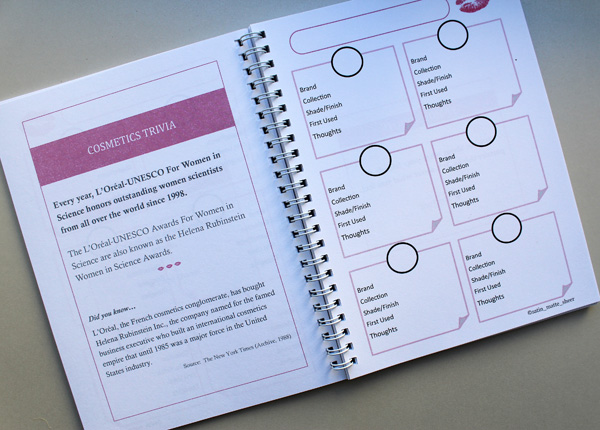

Another Instagram friend and lipstick fanatic has been making lipstick swatch books. These are kind of a new trend and in my opinion, far easier than taking photos of your lipsticks. Once again a sweet note was enclosed.

This lipstick swatch book is particularly lovely for its sprinkling of cosmetics trivia and important dates. (It also reminds me that I never started working on my daily makeup history calendar, sigh.) If you want one of your own you can purchase it here.

And that wraps up MM donations in 2020! I’m so incredibly grateful for these kind souls generously helping to build the collection. And while physical objects are amazing, it’s the notes and messages that come with them that mean the most. 🙂 Also, if you have a makeup object you think is historically significant, an object from the Curator’s wishlist, or anything else you’d like to give, please check out the Museum’s support page. I’m always looking for old fashion/women’s magazines too, along with ads and brochures and such…I can never have too much paper memorabilia!

Which one of these is your favorite? What’s the best gift you’ve ever received?