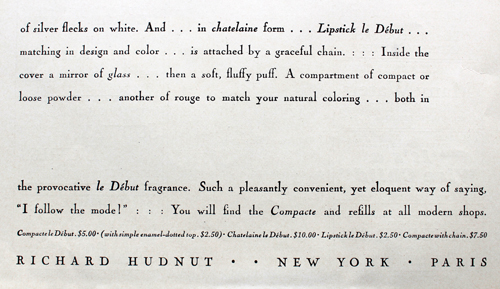

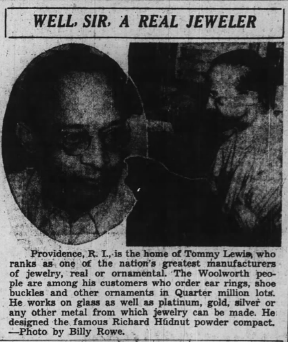

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

According to another article written in 1935 that I found online, Lewis was born into an impoverished family in Providence, Rhode Island. Undaunted by his circumstances and without the support of his parents or siblings, he attended RISD with the hopes of becoming a jeweler, earning a scholarship in the process. After graduating he worked for a leading jewelry manufacturer in Providence for several years, then struck out on his own.

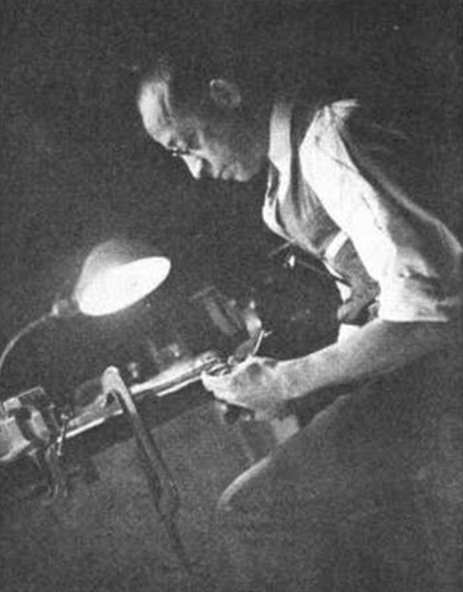

I was unable to find the date he started his company or much other information besides what was in these two articles. The 1935 online article says that he started his business 27 years prior, so I’m assuming he established it in 1908; however, the 1938 article says that he had been in business for 26 years, so maybe it was 1912. And there’s no information on his relationship with Hudnut other than what was in that article, so when he started making compacts for them is unclear. The only (rather patronizing) mention is as follows:1 “Visit the cosmetics department in any first class store, ask the clerk to show you a Richard Hudnut powder compact and then surprise him by telling him that he is looking at the work of a [Black] man. Everyone of those compacts was designed and produced here in a plant at 19 Calendar Street, the home of the Lewis Jewelry Manufacturing Firm. The same is true of their perfume bottles, for Mr. Lewis works on glass as well as platinum, gold, silver or any other metal from which jewelry or ornaments can be made. The Richard Hudnut people are among his biggest customers, but not his most consistent. That honor is reserved for other jewelry manufacturers who regularly send in their commissions for original designs in bracelets, watch chains and other novelty jewelry.” So it seems that while Hudnut was not the biggest source of business for Lewis’s company, we know that he was designing all of their compacts by 1938, and presumably earlier. When I purchased these compacts for the Museum I made sure to select ones that I could get specific dates for, i.e. compacts that were plausibly produced by Lewis given the approximate timeline, and also ones that seemed to be the most jewelry-inspired.

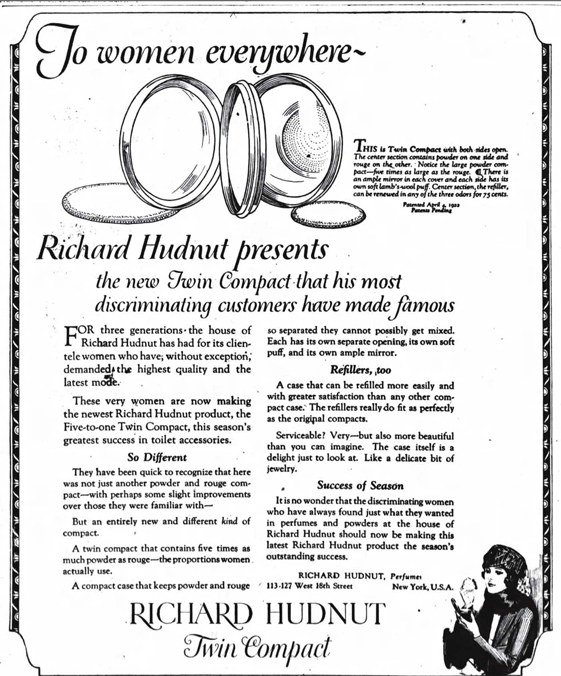

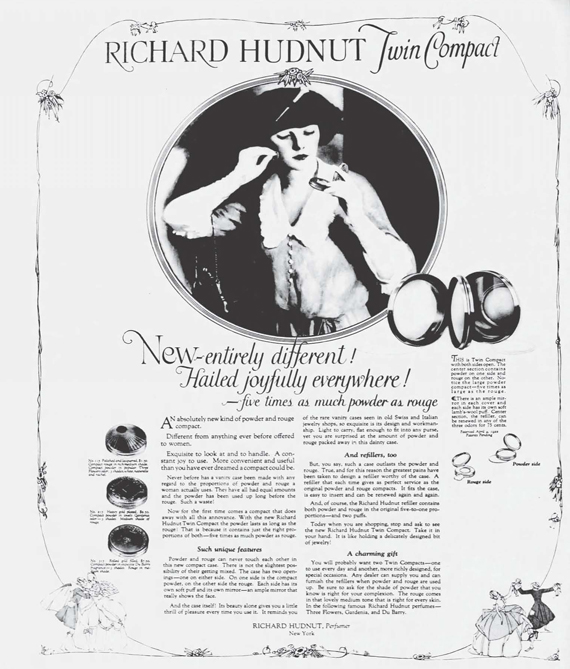

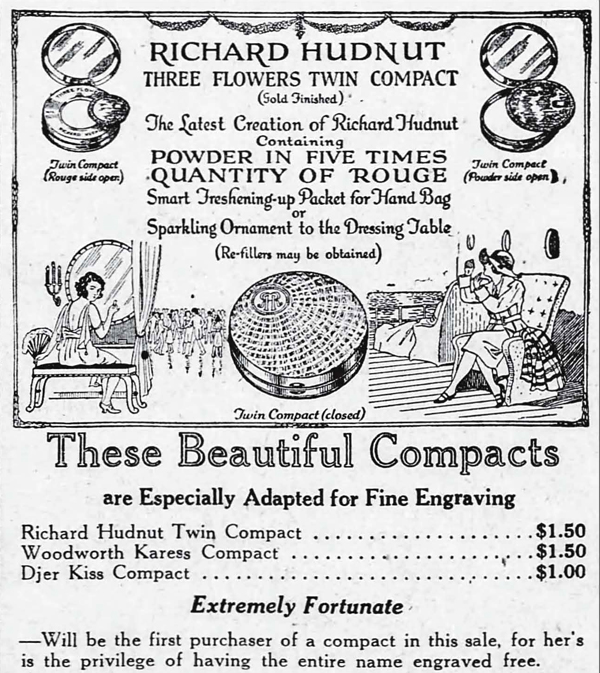

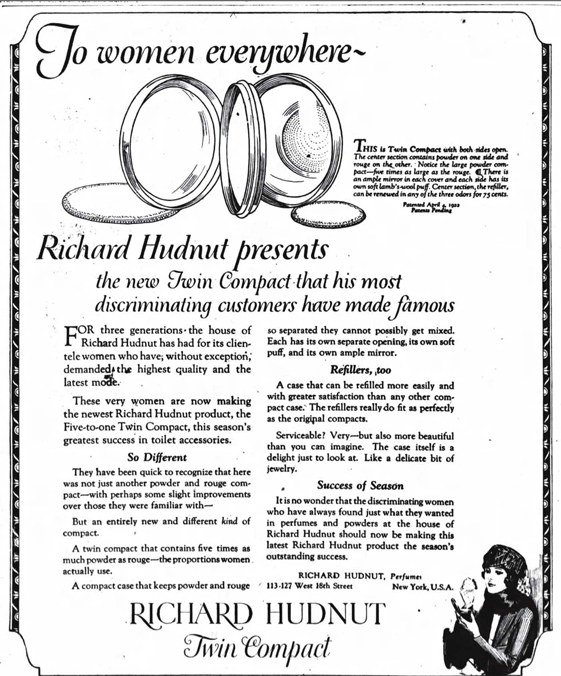

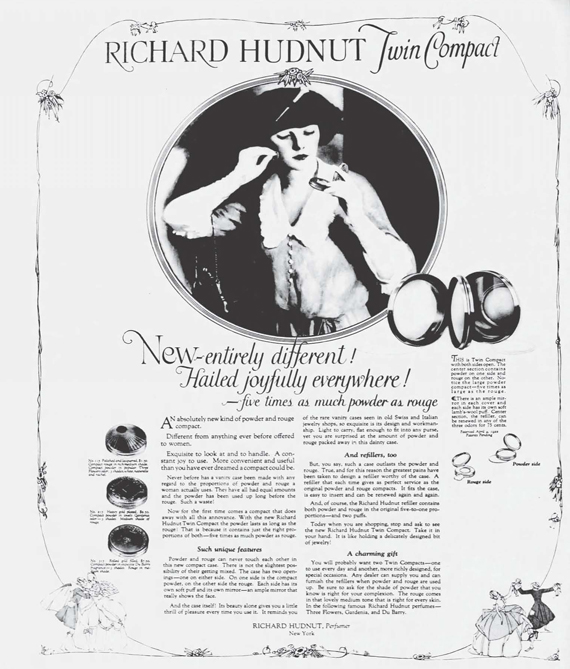

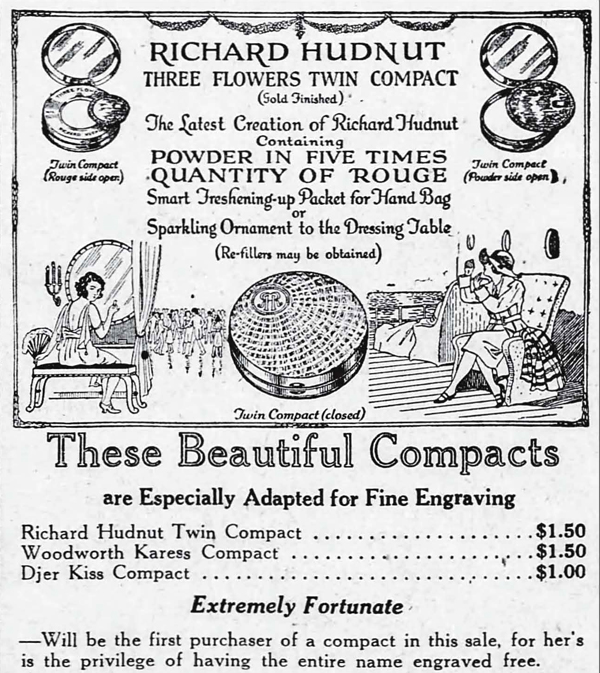

First up is the original “twin” compact, which was introduced in late 1922. I didn’t realize this until after I bought it, but this double case was designed by a man named Ralph Wilson in 1921 and patented in early 1922. Wilson was the New York representative for Theodore W. Foster and Bro. Company, a prominent compact and jewelry manufacturer. Foster, like Lewis, was also based in Providence, so maybe there might be some connection between this company and Lewis’s – perhaps this is the company Lewis worked for after graduating from RISD? In any case, we have proof that the twin compact was created by a company other than Lewis’s, so this is not his work. I still like to think, though, that Lewis may have apprenticed with Foster, grew familiar with Hudnut’s aesthetic and went on to earn the company’s favor over Foster.

How cool is this? You flip over the blush and there’s powder on the other side. Genius.

Hudnut’s Deauville fragrance was introduced in 1924. Again, no telling whether this was done by Lewis, but probably not given that it’s basically the same interior mechanism as the earlier twin compact.

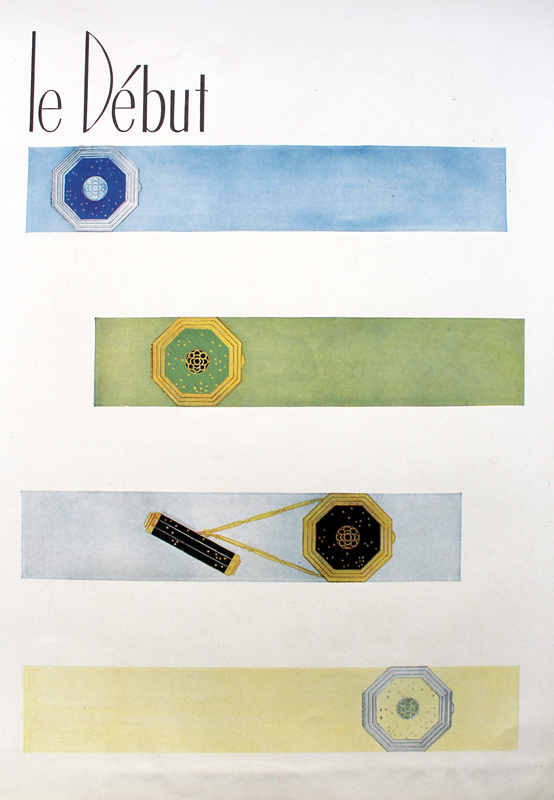

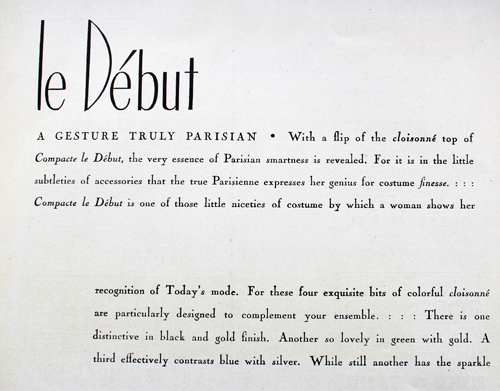

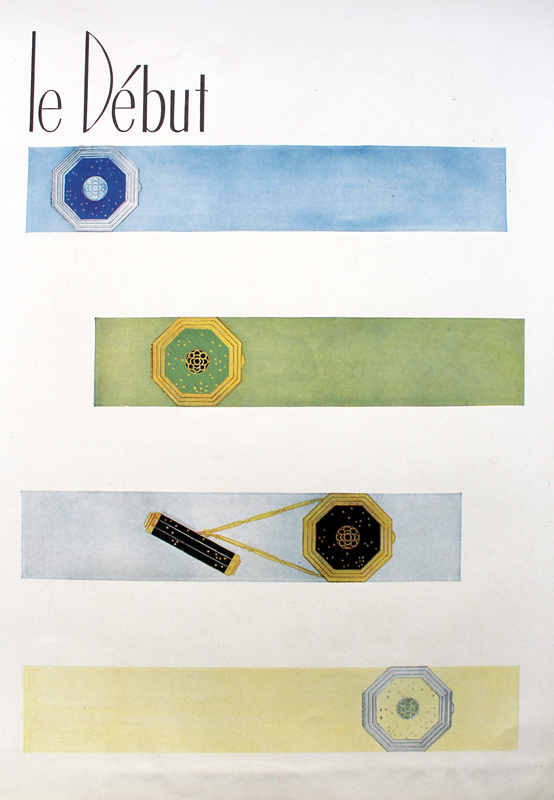

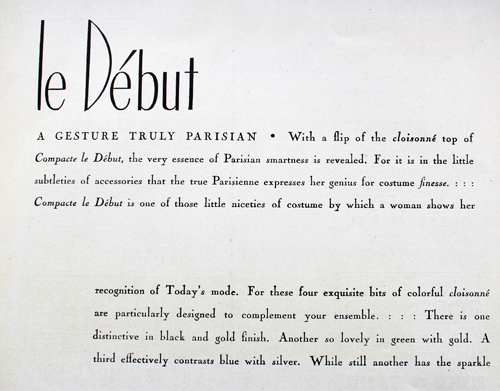

Le Début, a fragrance available in 5 different variants that were color-coordinated to their bottles and powder compacts, well, debuted in 1927. I was fortunate enough to track down an original ad for these beauties. They’re actually pretty common – I was able to find all the colors shown in the ad – but in the end I thought the black one was the most elegant. (Okay, I really love the silver one too!)

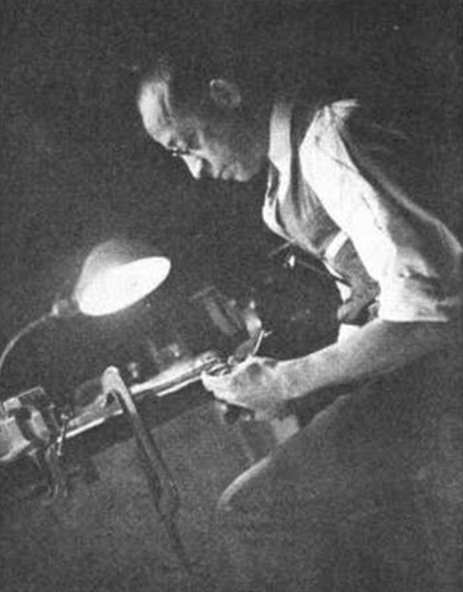

In the 1938 photo below it states that Lewis designed the “famous Richard Hudnut compact”, but I really have no idea which one they’re referring to. It could be Le Début, or it could be the “triple vanity” compacts designed in the mid ’30s.

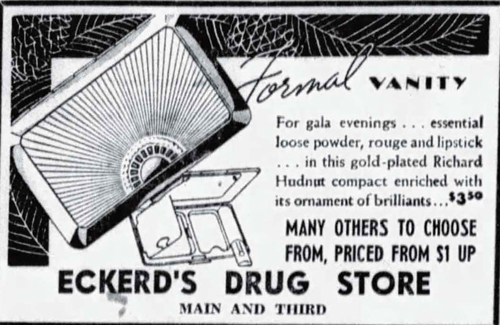

This enameled, oh-so-Deco case came out in 1936, according to the newspaper ads I found, and the last mention of it was in 1938. Again, it’s funny how certain objects call to you. This one was also available in a variety of colors, but I just knew the red belonged in the Museum.

The triple vanities had three compartments for powder, blush and lipstick.

The ad also mentions jewelry several times, so I’m hopeful it was made by Lewis’s hand.

Lastly, I picked up this stunner, which dates to about 1939. Evidently between this one, the Three Flowers compact and the silver Evans compacts I have a thing for sunburst patterns, probably because they remind me of glorious sunny days.

How exquisite is this jewel detail? And in such impeccable shape for a nearly 80 year-old compact – it’s mind-boggling that none of the stones are missing.

To give you a sense of how dainty and small these triple vanities are, here they are with one of NARS’ highlighting trios.

Getting back to Lewis, I can’t say for sure whether his company was responsible for any of these compacts; I can only hope at least some of these jewelry-inspired designs were his. The fact that the 1935 article doesn’t specifically mention Richard Hudnut makes me think that perhaps Lewis wasn’t designing compacts for Hudnut until somewhere between 1936-1938. But it’s also entirely possible he had been producing compacts for them for years. In any case, I want to highlight just how difficult it was for a Black man in the 1900s to not only get out of poverty, but graduate from one of the top design schools in the country AND start his own business that eventually employed up to 60 workers in the busy seasons. As the 1935 profile states: “But jeweler, designer, silversmith? What chance would he have? Where could he work? Who ever heard of a [Black] man, a designer, a master craftsman in the jewelry trade of all trades! One can imagine what would have been Lewis’s fate if his ambitions had been left in the hands of some of the so-called vocational guidance counselors who are at the present time shaping the lifework of many [Black] students in the public schools of our large cities. According to the formula which they use, there are no [Black] jewelers now in existence, hence no future; it would be impossible for a [Black] silversmith to get a job since he cannot belong to the union, and the white jewelers would not employ him anyhow.” Through incredibly hard work and innate talent, Lewis persevered, not only becoming a success himself but also helping others do the same. Most of his employees were Black, and Lewis provided them with better wages than other jewelry firms in Providence as well as training.

I just wish I could have found more information and photos to make for a somewhat complete biography. Searching online for Lewis’s company yielded nothing, as did basic searches for Lewis himself. I ended up contacting the Rhode Island Historical Society and they kindly provided census records indicating his year of birth (1880), but said they didn’t have any business records related to Lewis’s company, which I think is bizarre. If it was as prolific as the articles claim it was, and if it really did provide hundreds of thousands of pieces of costume jewelry to the likes of Saks and Woolworth’s and compacts for Hudnut, I find it very strange that there are absolutely zero traces of his company left save for these two profiles. Especially since the 1938 article even gives the address of his workshop – with that specific type of information there should be historic maps or architectural records listing it. He also apparently had over 200 patents to his name, none of which I was able to find. I guess the saddest part is that there are tons of other stories like Lewis’s, and we simply don’t hear about them. So many histories for non-white people are erased or buried, and I really wanted to bring Lewis’s story to the surface because it was truly outstanding (and not only because it’s Black History Month…I just so happened to find the newspaper article around a month ago and thought the timing worked out nicely). I really hope this post didn’t come across as patronizing or me highlighting a “token” Black person.2 I find Lewis’s story impressive not because I can’t believe a Black man could ever be creative and intelligent enough to start a jewelry firm, but because of all he had to overcome to achieve his goals. “Perhaps it is the memory of a [Black] boy with a dream to become a jeweler, a silversmith, a designer, a [Black] boy who kept his dream despite the doubts of his family from within and racial prejudice from without. For Thomas Lewis is an artist and so he believes in young men and young women with dreams.”

Thoughts?

Update, 11/24/2022: One of the Museum’s Instagram followers alerted me to a video made by a vintage compact collector who mentioned Tommy Lewis while showing some of her Hudnut collection. It got me thinking whether anything else on Lewis had been discovered and lo and behold, two students from Rhode Island College were able to unearth some more information, including a map showing where his store and factory were! While it didn’t shed any light on Lewis’s relationship with the Hudnut company, their article surely adds more to this important piece of history. Lewis was born on April 5, 1880 and graduated from RISD in 1902. In 1925 a lacquer explosion caused a fire at Lewis’s shop located at 171 Eddy Street, which damaged much of the building. I’m wondering if some of the early business records were lost in that fire. Throughout his life, in addition to providing training and employment for Black workers, he was a philanthropist and active in the YMCA and other community organizations. Lewis passed away in 1958. I can only hope someone writes a full biography of this exceptionally talented man, but in the meantime sure to check out the article at rhodetour.org. Oh, and they even included the Makeup Museum’s original article as a “related resource”. I’m so honored!

1 I spent several hours googling whether it was acceptable to type the word “c*lored” if I was quoting from an old newspaper article. In the end I realized I personally didn’t feel comfortable using it even if it was a quote, so I replaced it with “black”.

2 I rarely, if ever, highlight makeup histories featuring people of color, i.e. Madam C.J. Walker, Annie Turnbo Malone, etc. because I’m not sure whether it’s okay for a white person to do that – while I think their stories absolutely need to be heard and recorded, once again I fear that it would come off as whitesplaining or tokenizing if I attempted to write about them. In the case of Tommy Lewis, there was such scant information available I’d figure I’d make an exception in order to at least introduce him and his work.

Save

Save

Save

Save

It's the most wonderful time of the year…to look at vintage Christmas makeup ads, that is! You know I can't get enough of these, so here's a quick roundup (in no particular order) of some I added to the Museum's collection this year. 🙂

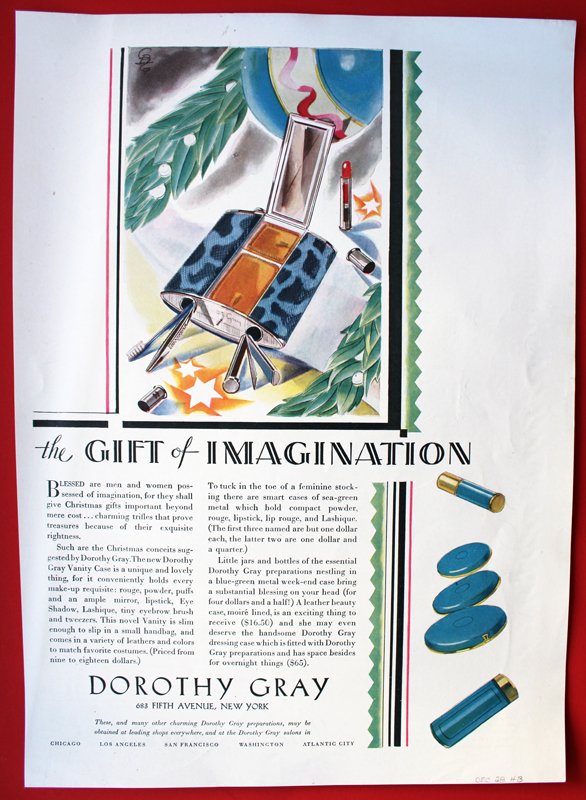

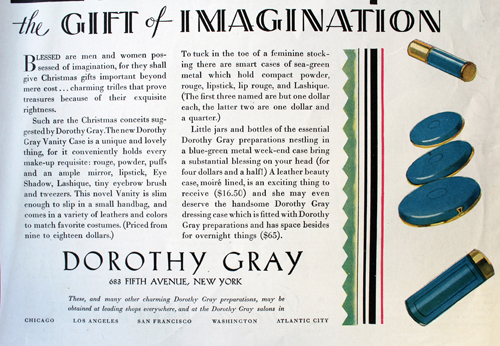

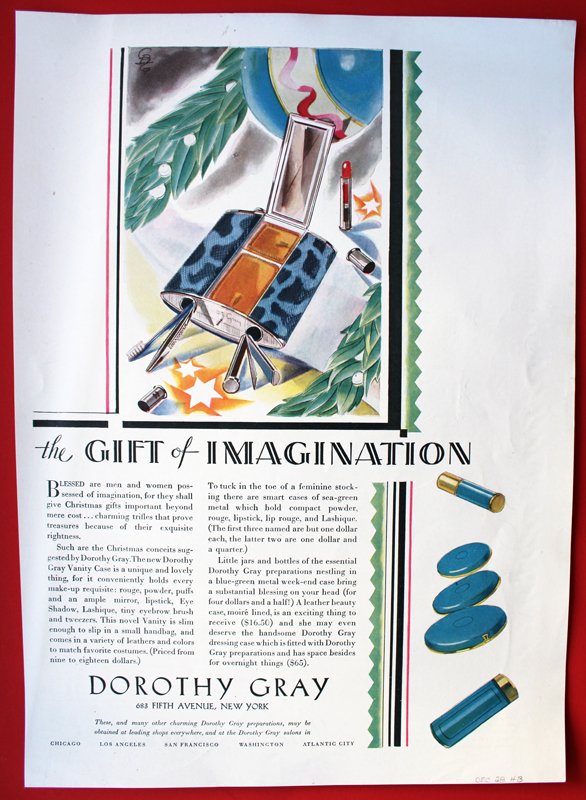

I have many Dorothy Gray ads, but not any from the '20s. Their early packaging was so sleek.

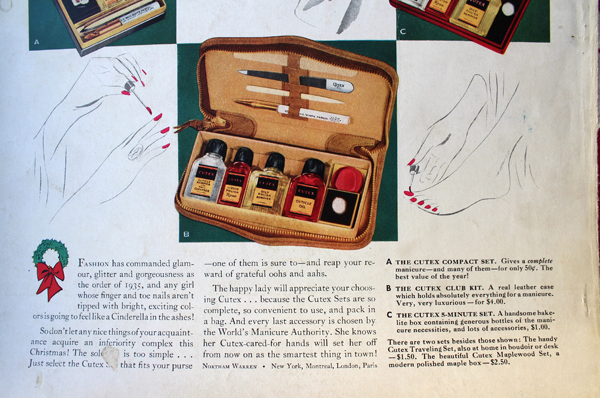

Apparently you can avoid an inferiority complex with a manicure set. LOL.

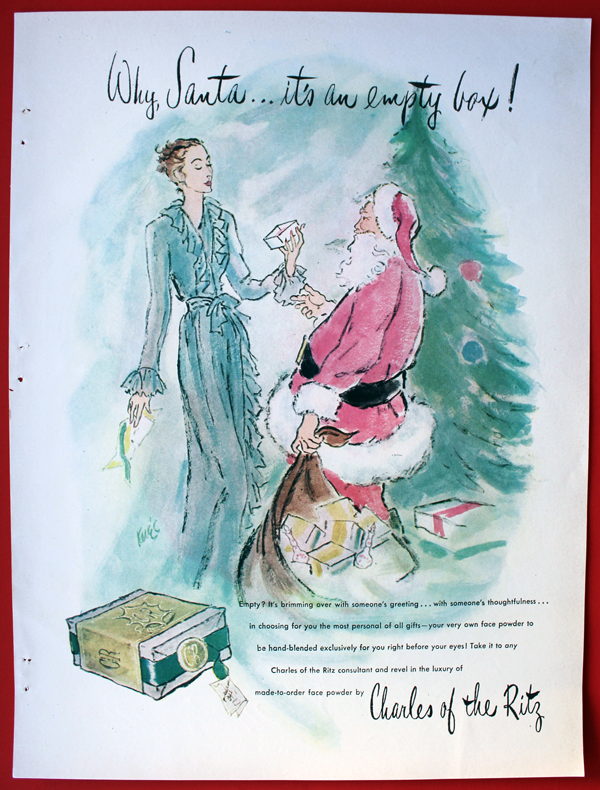

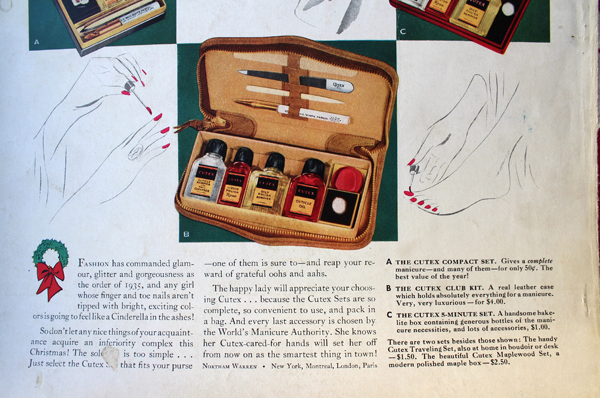

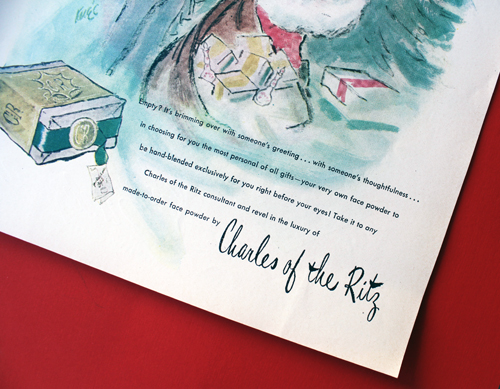

Santa, you jerk! Why did you give me an empty box? Now I have to go to the store and have it filled?! That's not a good present!

I understand custom powder was Charles of the Ritz's bread and butter and you had to actually go to a counter to get your own personal blend, but I'd still be pissed if someone gave me this. Get me a nice compact!

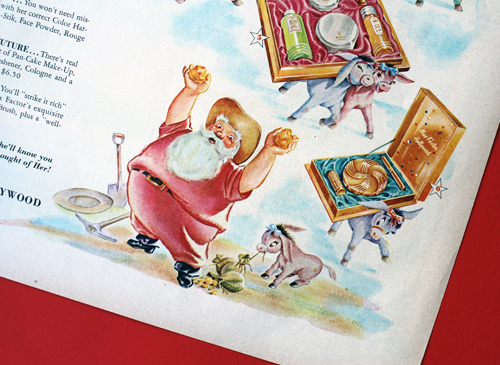

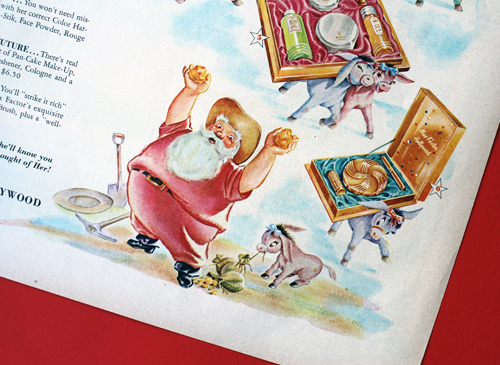

Santa gave considerably better gifts in this ad. I'm a bit confused about the presence of donkeys (shouldn't it be reindeer?), but I do love the overall cartoon-y look of this one.

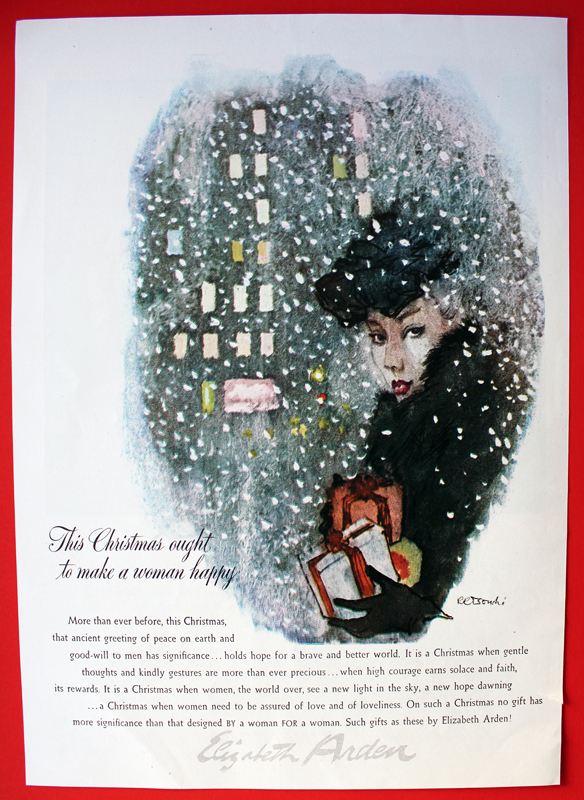

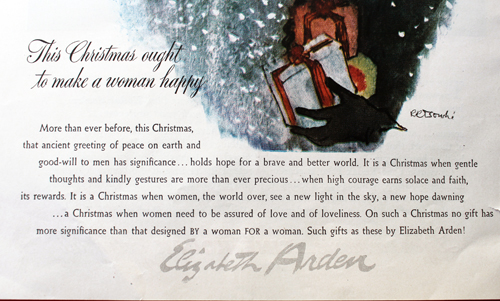

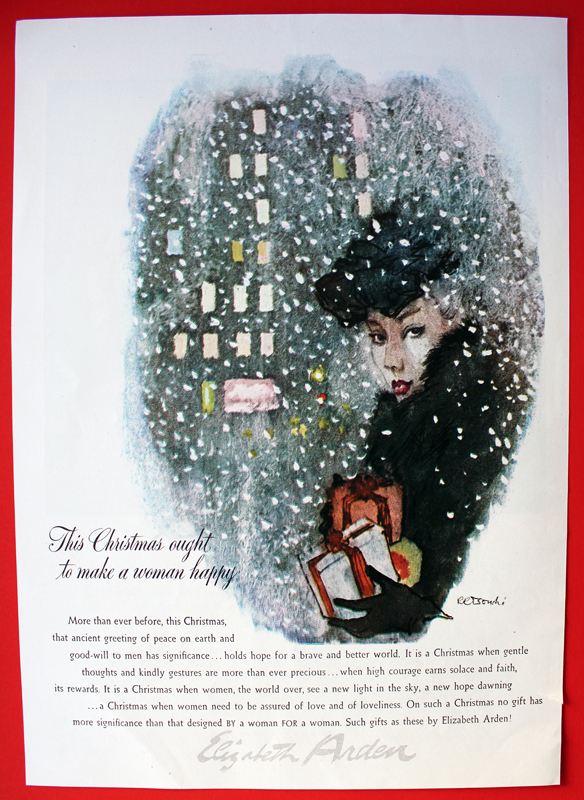

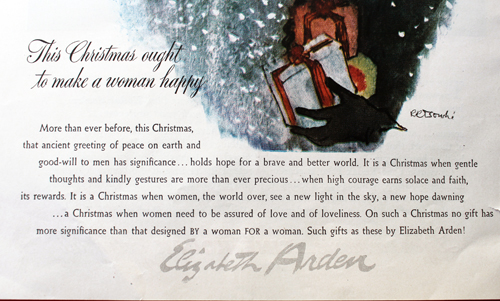

René Bouché (1905-1963) was Elizabeth Arden's head advertising illustrator in addition to working for Vogue. If you see an illustrated ad for Elizabeth Arden from the 40s or 50s most likely it was done by Bouché's hand. I believe this is the first ad by this artist to join the Museum's collection. 🙂

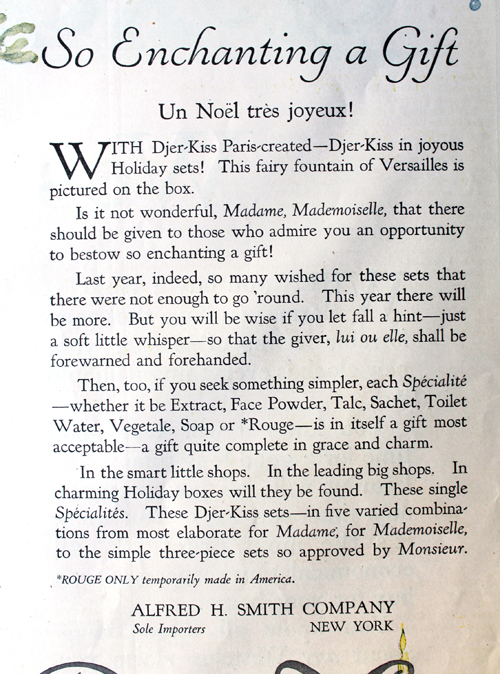

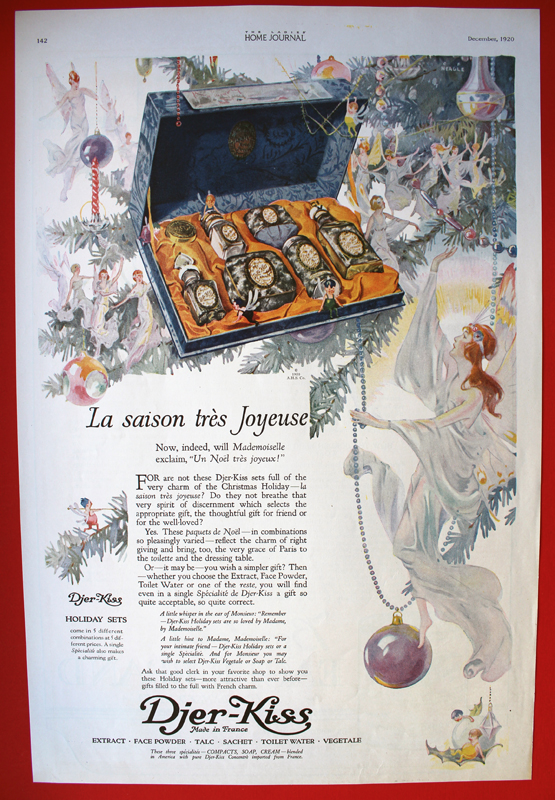

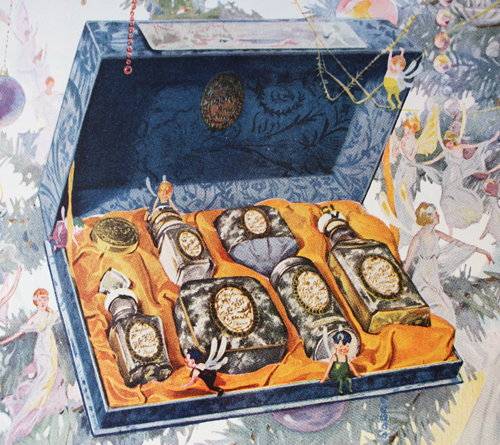

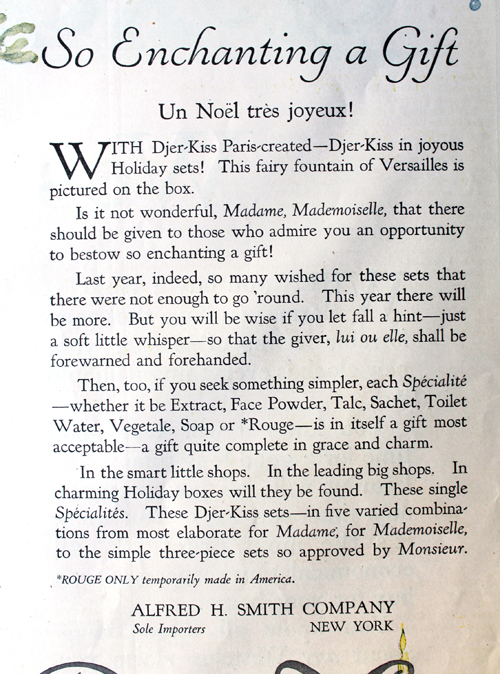

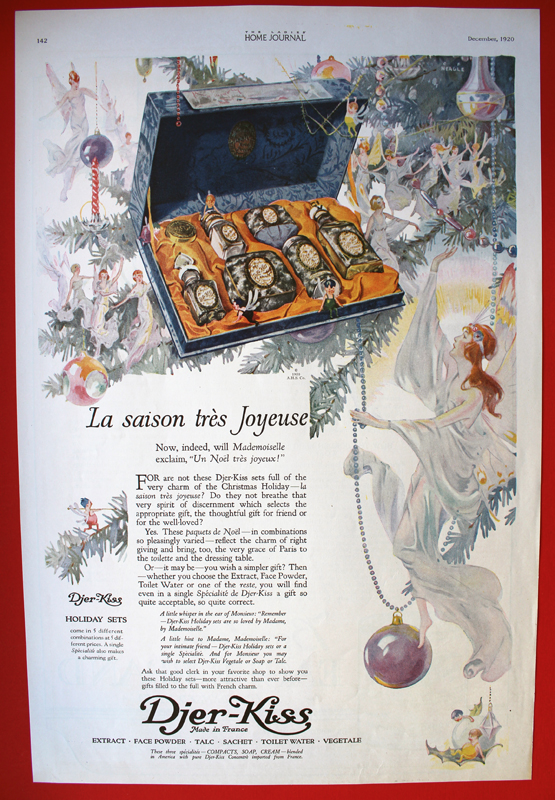

I can't recall how I stumbled across these Djer-Kiss ads, but I'm so pleased I found them! Djer-Kiss "Kissing Fairies" compact has been on my wishlist for a long time, but the ads are just as gorgeous as the compacts. I'm hell-bent on collecting all of them, as they're simply beautiful and feature a variety of illustrators. Collecting Vintage Compacts has an amazingly thorough history of the company, which makes me want them all the more. I believe the illustrator for this one was Willy Pogany, although I couldn't find a signature anywhere so I can't be sure.

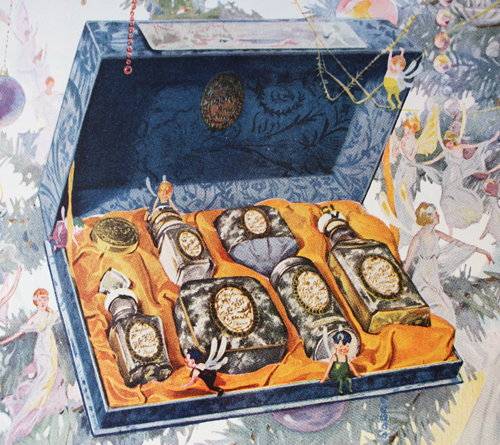

This one is by C.F. Neagle, who does a breathtaking job of capturing iridescence – from fairy wings to Christmas baubles, there's a multi-colored sheen that seems to pop off the page.

I love all the little sprites flitting about the gift box, particularly the ones hanging off the top and sitting on the edge. Incredibly charming, no?

So that concludes 2017's vintage Christmas ad roundup! Which one was your favorite? I love all of these, of course, but I'm partial to the very silly Max Factor ad and the beautiful Djer-Kiss ads.

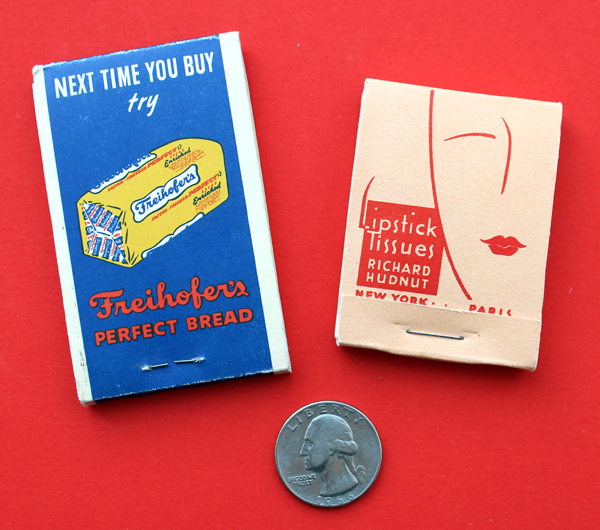

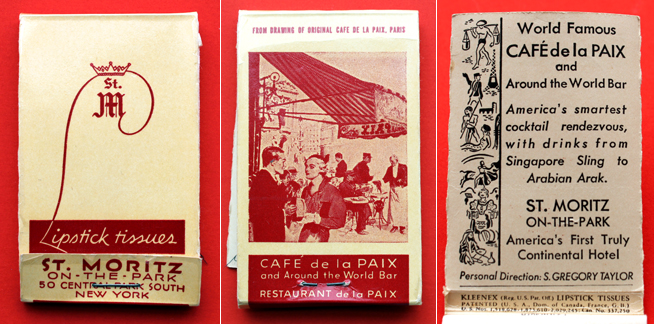

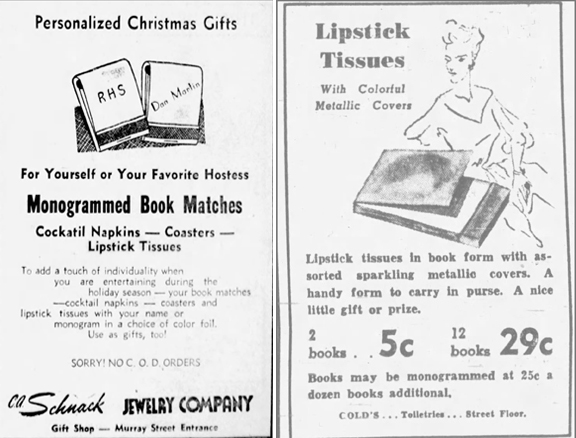

The life of a makeup museum curator is insanely glamorous. For example, a lot of people go out on Friday nights, but not me – I have way more thrilling plans. I usually browse for vintage makeup at Ebay and Etsy on my phone while in bed and am completely passed out by 8pm. EXCITING. It was during one of these Friday night escapades that I came across a fabulous box of vintage lipstick pads and naturally, that sent me down quite the rabbit hole. Today I’m discussing a cosmetics accessory that has gone the way of the dodo: lipstick tissues. This is by no means a comprehensive history, but I’ve put together a few interesting findings. I just wish I had access to more than my local library (which doesn’t have much), a free trial subscription to newspapers.com and the general interwebz, as anyone could do that meager level of “research”. I would love to be able to dig deeper and have more specific information, but in lieu of that, I do hope you enjoy what I was able to throw together.

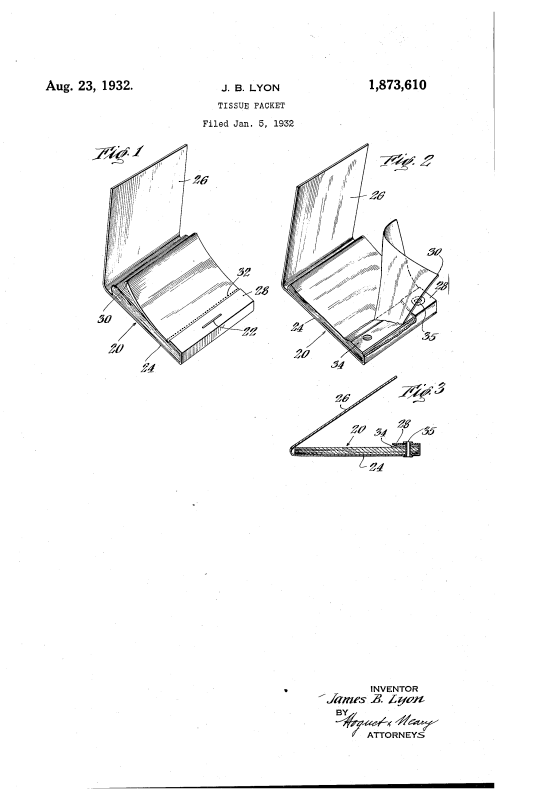

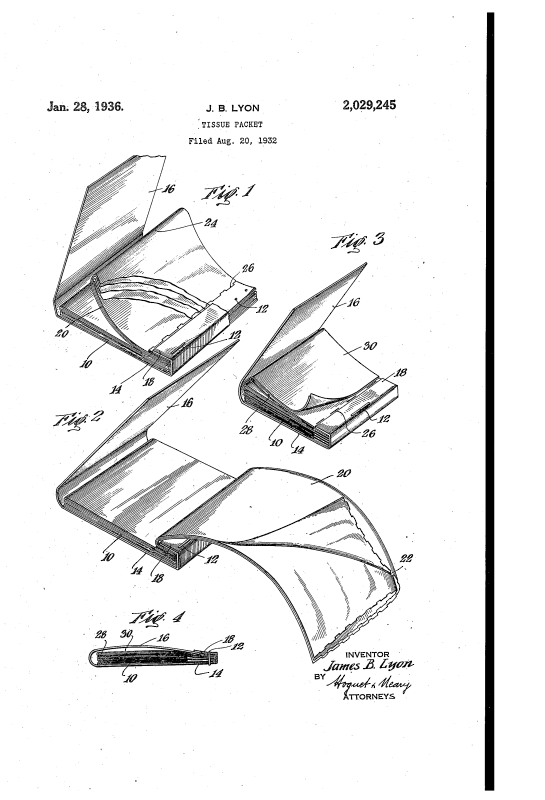

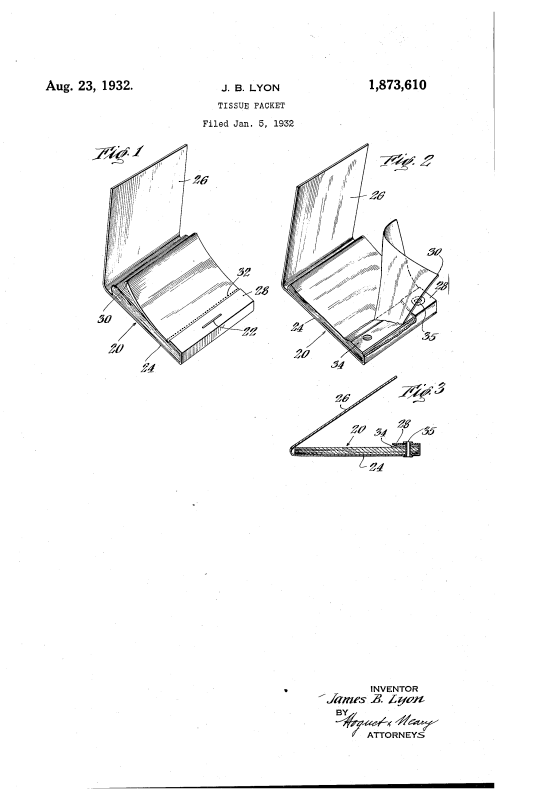

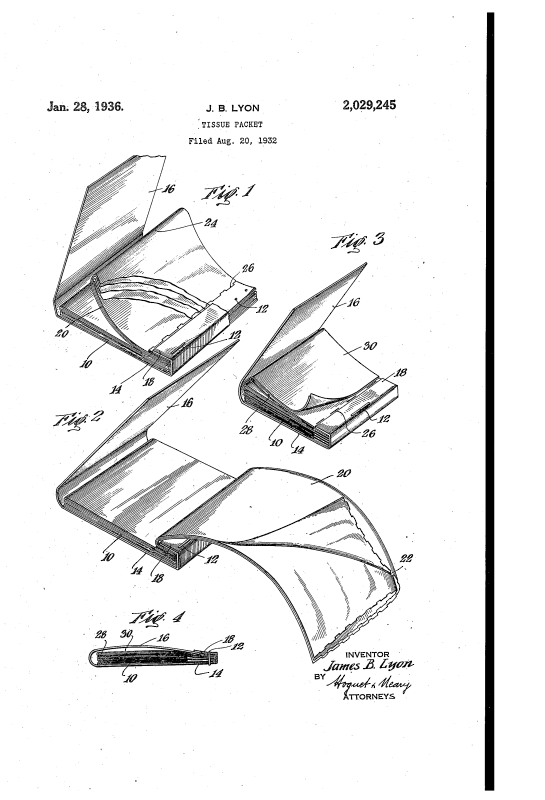

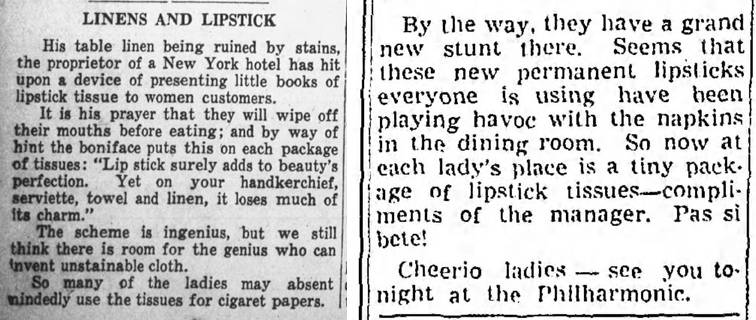

The earliest mention of lipstick tissues that I found was January 1932. It makes sense, as several patents were filed for the same design that year.

(images from google)

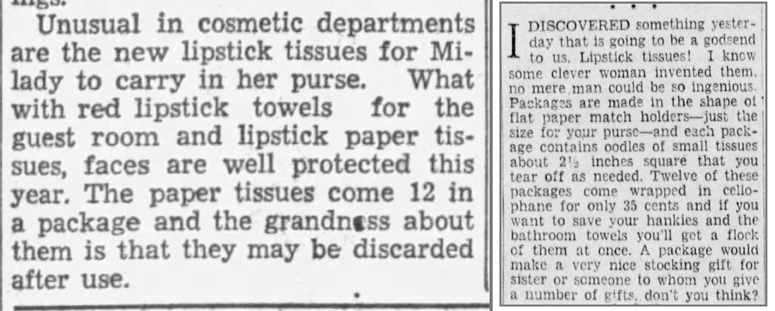

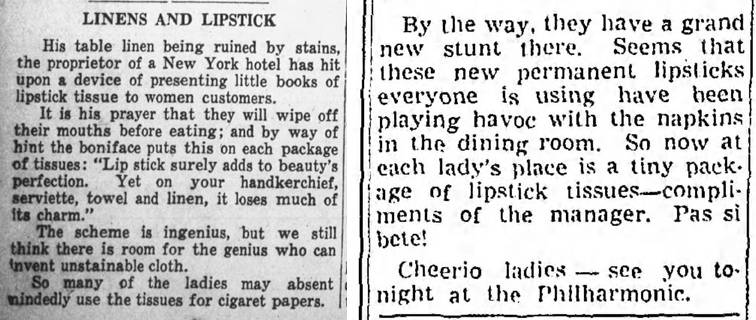

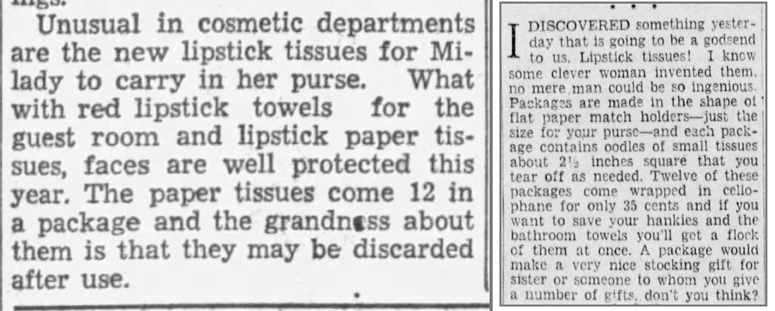

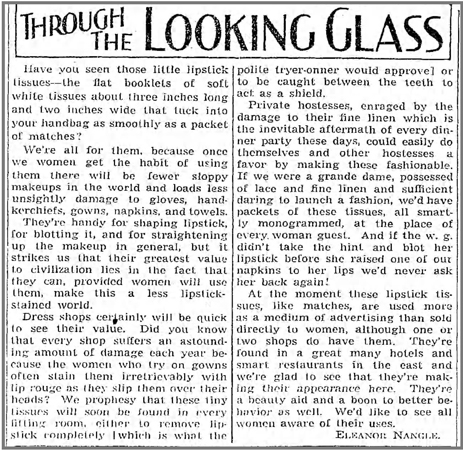

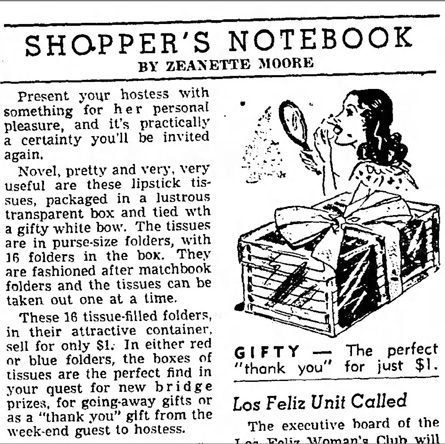

While they might have existed in the 1920s, I’m guessing lipstick tissues didn’t become mainstream until the early 30s, as this December 1932 clipping refers to them as new, while another columnist in December 1932 says she just recently discovered them (and they are so mind-blowing they were clearly invented by a woman, since “no mere man could be so ingenious”.)

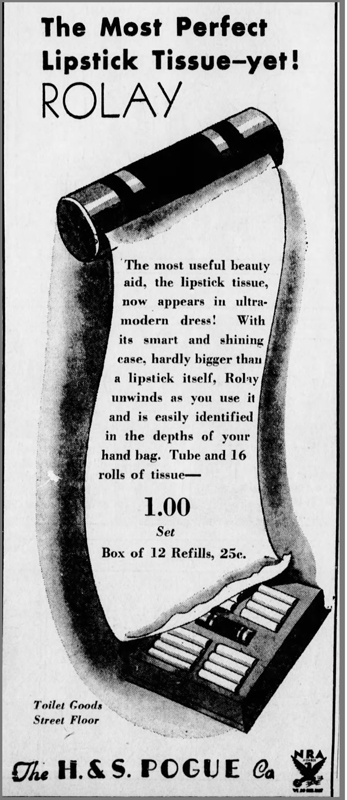

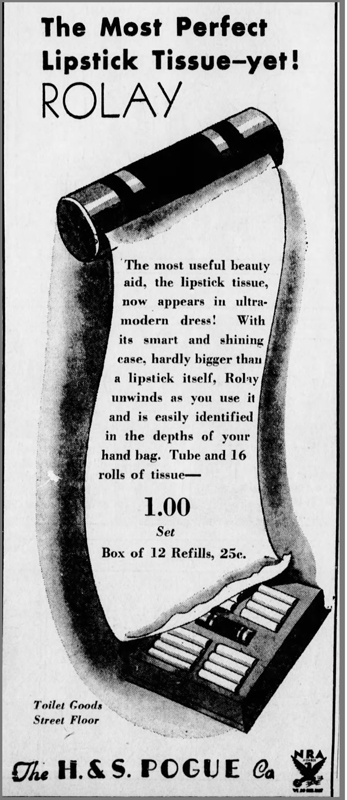

In addition to the tear-off, matchbook-like packages, lipstick tissues also came rolled in a slim case.

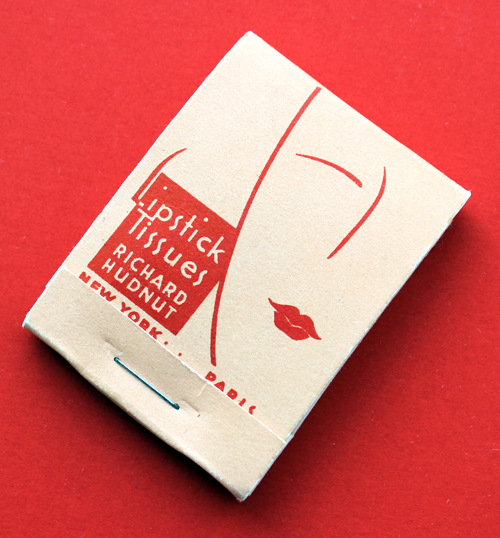

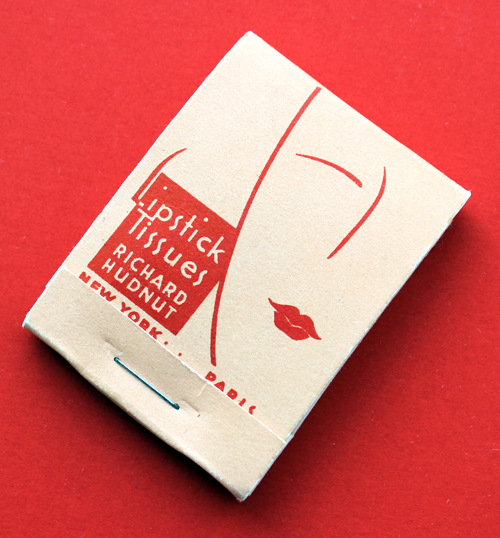

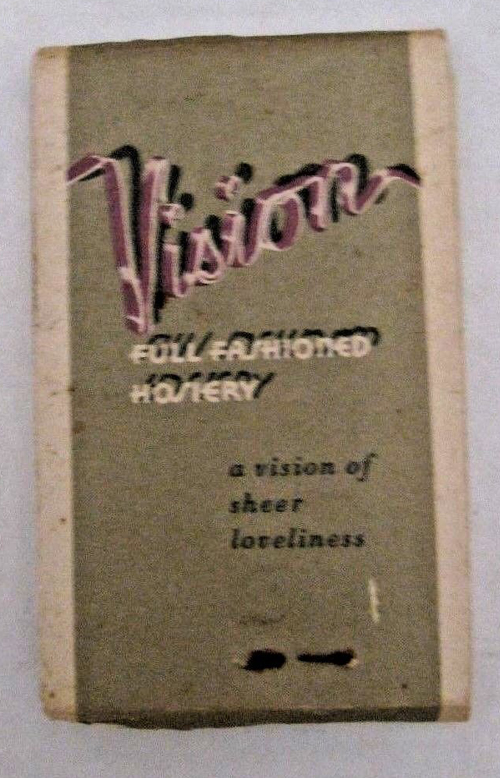

This lovely Art Deco design by Richard Hudnut debuted in 1932 and was in production at least up until 1934. I couldn’t resist buying it.

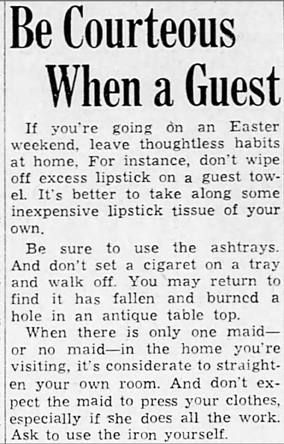

By 1935, restaurants and hotels had gotten wind of lipstick tissues’ practicality for their businesses, while beauty and etiquette columnists sang their praises. Indeed, using linens or towels to remove one’s lipstick was quickly becoming quite the social blunder by the late 30s.

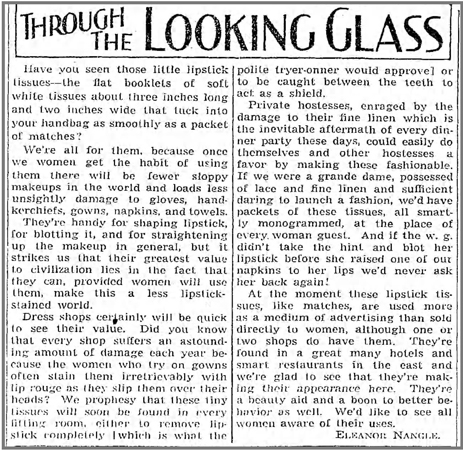

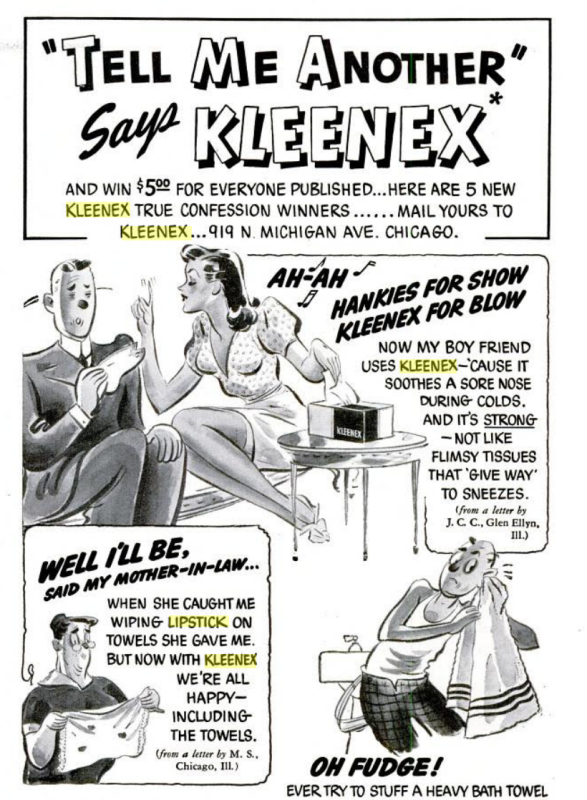

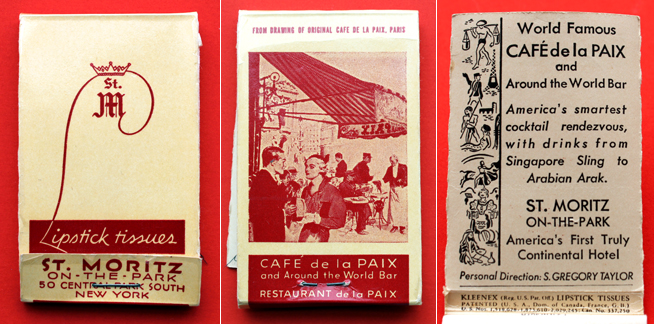

Kleenex was invented in 1924, but it wasn’t until 1937, when the company had the grand idea to insert tissues specifically for lipstick removal into a matchbook like package, that these little wonders really took off. You might remember these from my post on the Smithsonian’s collection of beauty and hygiene items. The warrior/huntress design was used throughout 1937 and 1938.

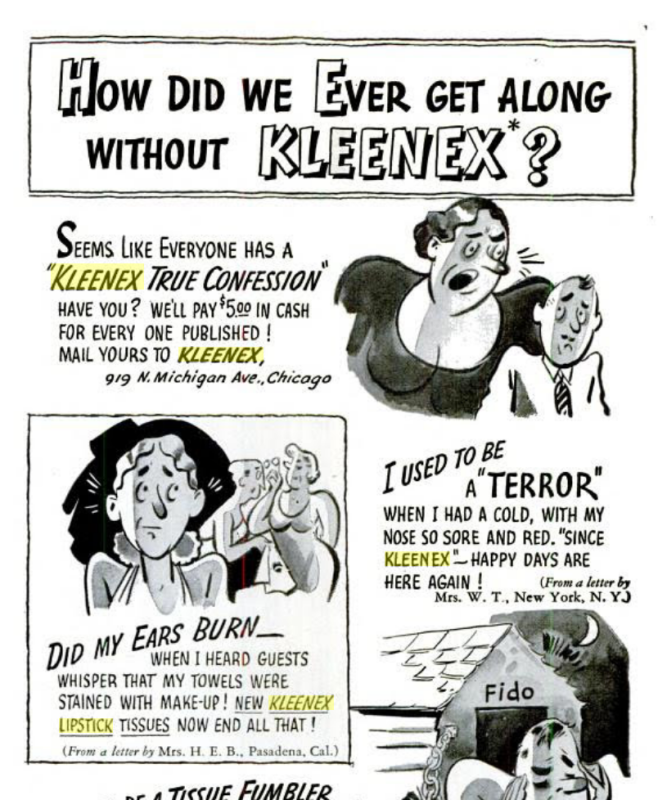

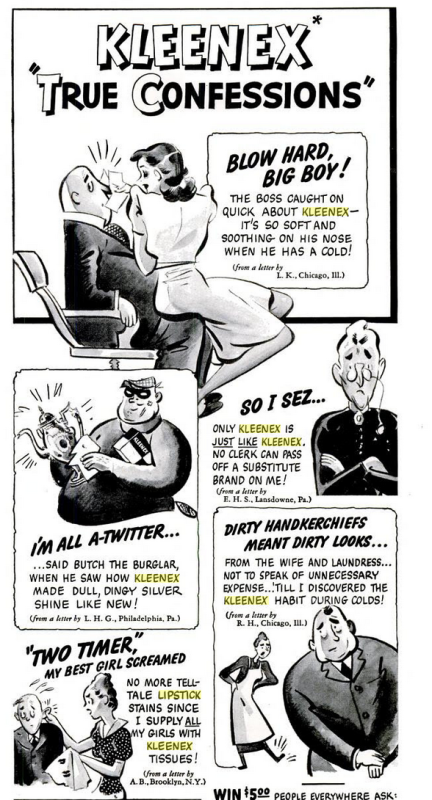

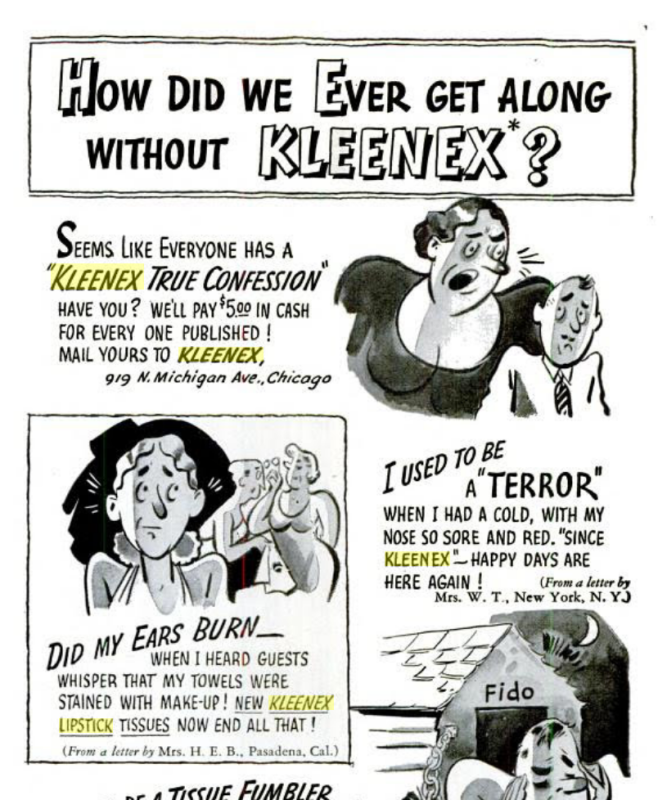

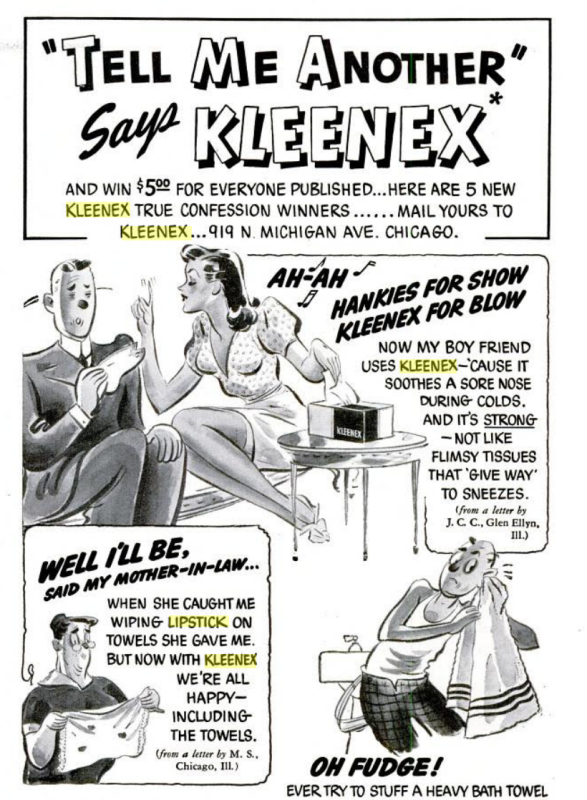

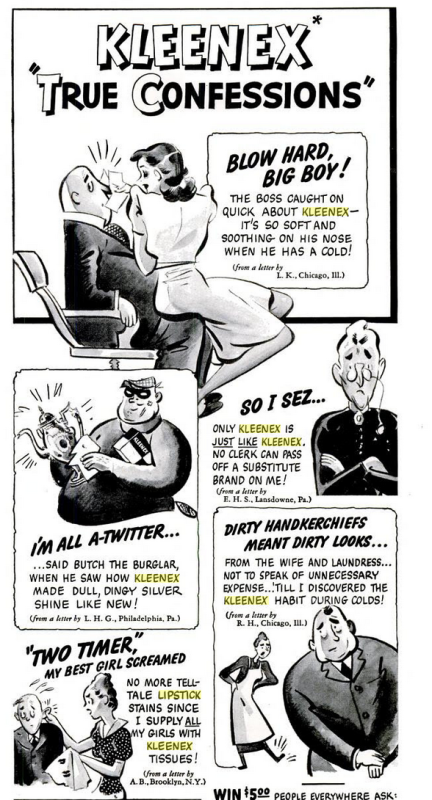

Kleenex started upping the ante by 1938, selling special cases for their lipstick tissues and launching campaigns like these “true confessions”, which appeared in Life magazine (and which I’m sure were neither true nor confessions.) With these ads, Kleenex built upon the existing notion that using towels/linens to remove lipstick was the ultimate etiquette faux pas, and one that could only be avoided by using their lipstick tissues.

These ads really gave the hard sell, making it seem as though one was clearly raised by wolves if they didn’t use lipstick tissues. Or any tissues, for that matter. Heaven forbid – you’ll be a social pariah!

Look, you can even use these tissues to cheat on your girlfriend! (insert eyeroll here)

(images from books.google.com)

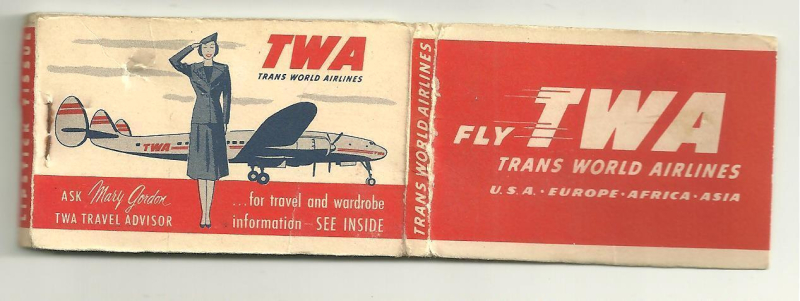

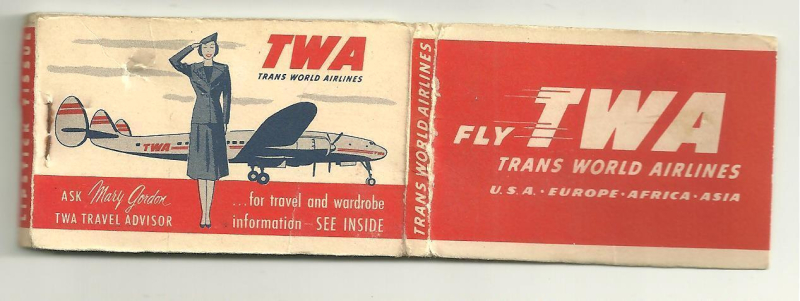

Not only that, Kleenex saw the opportunity to collaborate with a range of companies as a way to advertise both the companies’ own goods/services and the tissues themselves. By the early ’40s it was difficult to find a business that didn’t offer these gratis with purchase, or at least, according to this 1945 article, “national manufacturers of goods women buy.” And by 1946, it was predicted that women would be expecting free tissue packets to accompany most of their purchases.

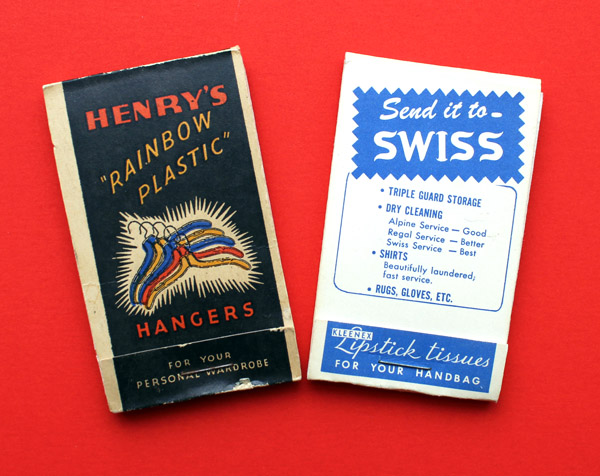

Needless to say, most of them consisted of food (lots of baked goods, since apparently women were tethered to their ovens), and other domestic-related items and services, like hosiery, hangers and dry cleaning.

(images from ebay.com)

(images from ebay.com)

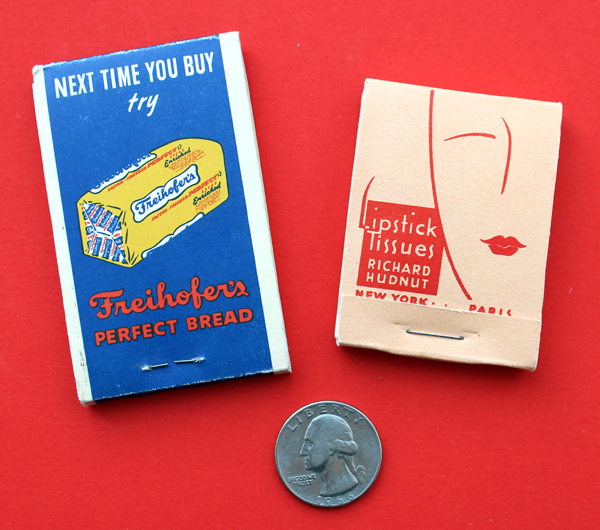

(images from ebay and etsy.com)

(images from ebay and etsy.com)

(images from ebay.com)

(images from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

Naturally I had to buy a few of these examples for the Museum’s collection. Generally speaking, they’re pretty inexpensive and plentiful. The only one I shelled out more than $5 for was the Hudnut package since that one was a little more rare and in such excellent condition. Interestingly, these have a very different texture than what we know today as tissues. Using contemporary Kleenex to blot lipstick only results in getting little fuzzy bits stuck to your lips, but these vintage tissues have more of a blotting paper feel, perhaps just a touch thicker and ever so slightly less papery. It could be due to old age – paper’s texture definitely changes over time – but I think these were designed differently than regular tissues you’d use for a cold.

Anyway, Museum staff encouraged me to buy the cookie one. 😉

I took this picture so you could get a sense of the size. It seems the official Kleenex ones were a little bigger than their predecessors.

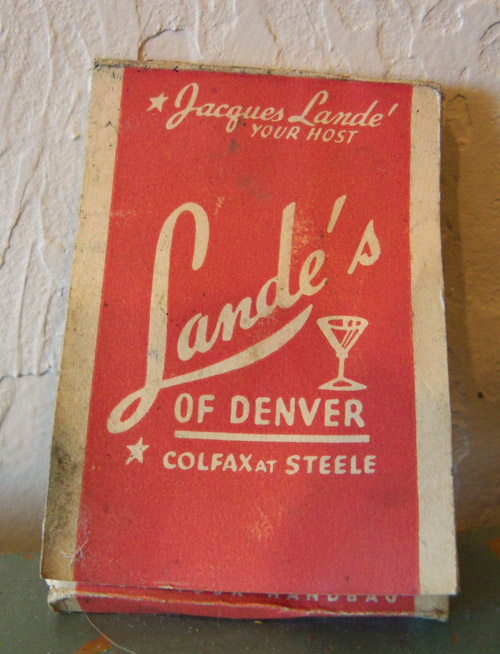

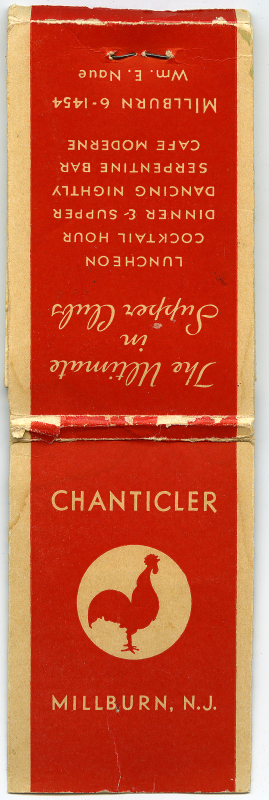

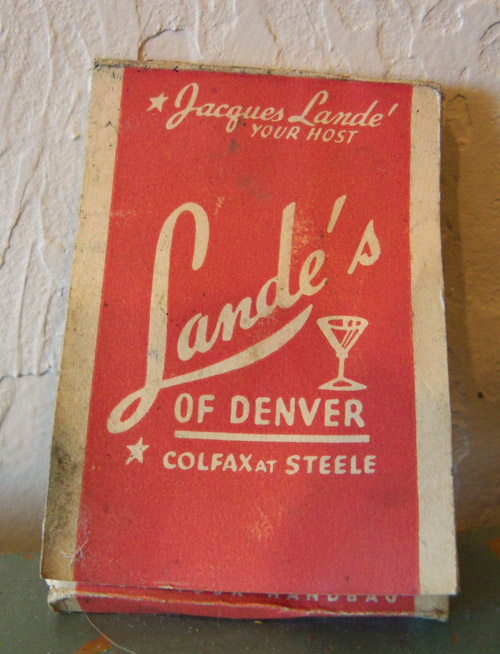

Wouldn’t it be cool to go to a restaurant and see one of these at the table? It would definitely make the experience seem more luxurious. I certainly wouldn’t feel pressure to use them for fear of committing a social sin, I just think it would be fun.

(image from etsy.com)

(image from mshhistoc.org)

I figured having a restaurant/hotel tissue packet would be a worthy addition to the Museum’s collection, since it’s another good representation of the types of businesses that offered them. I’d love to see a hotel offer these as free souvenirs.

Here’s an example that doesn’t fit neatly into the baked goods/cleaning/hotel categories.

(image from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

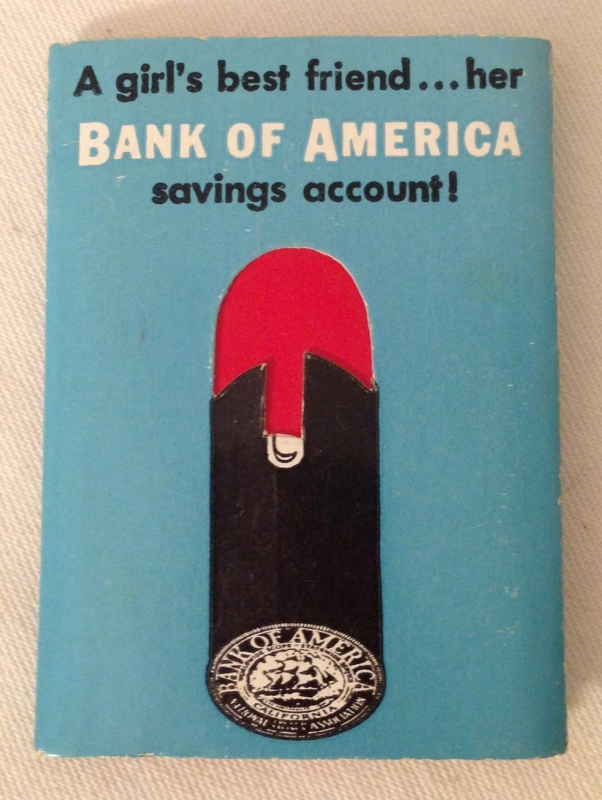

This one is also interesting. Encouraging women to be fiscally responsible is obviously more progressive than advertising dry cleaning and corn nut muffins, but it’s important to remember that at the time these were being offered by Bank of America (ca. 1963), a woman could have checking and savings accounts yet still was unable to take out a loan or credit card in her own name. One step forward, 5 steps back.

(image from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

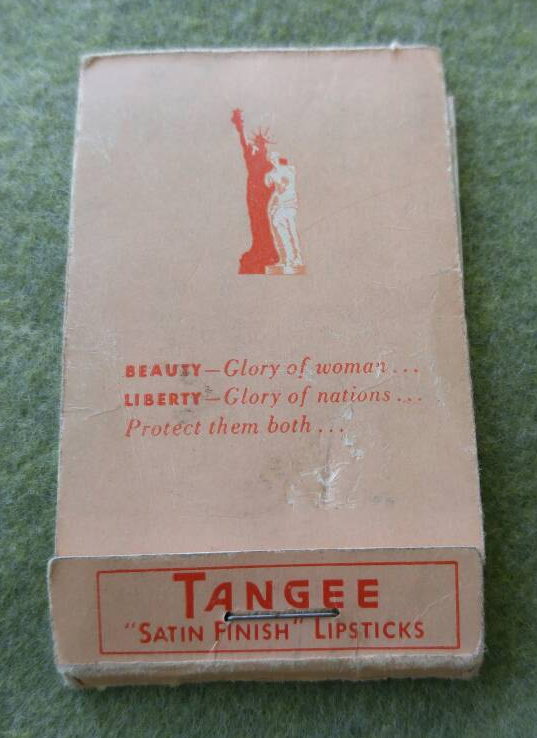

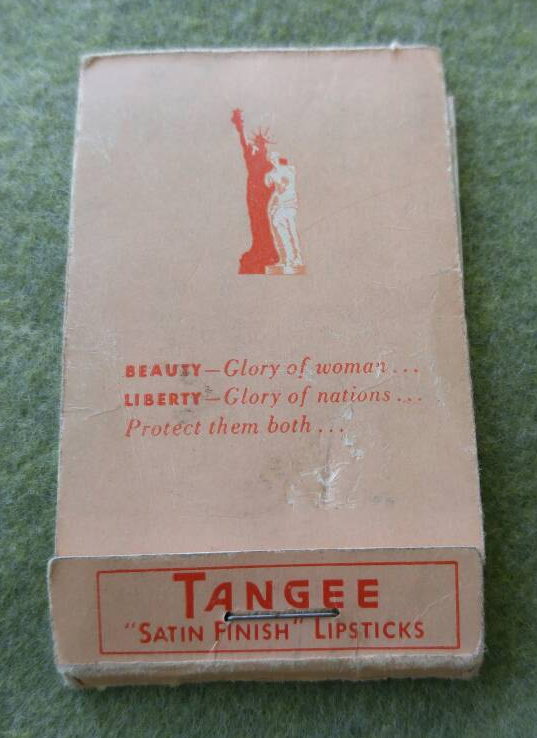

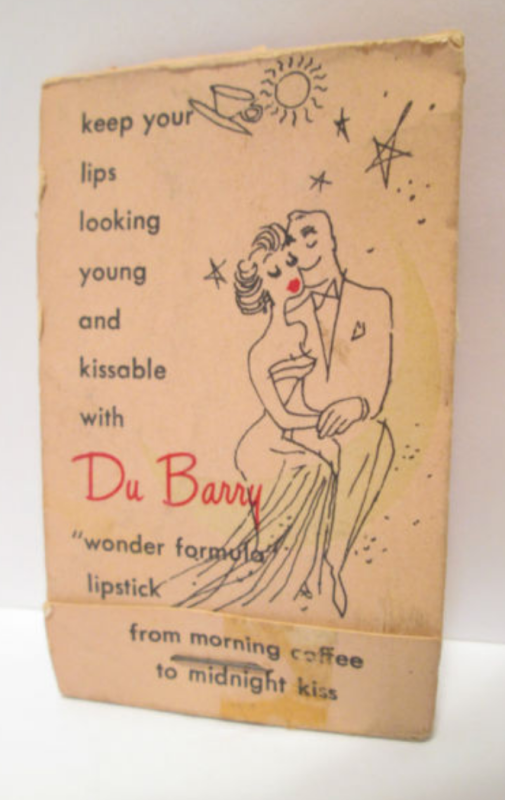

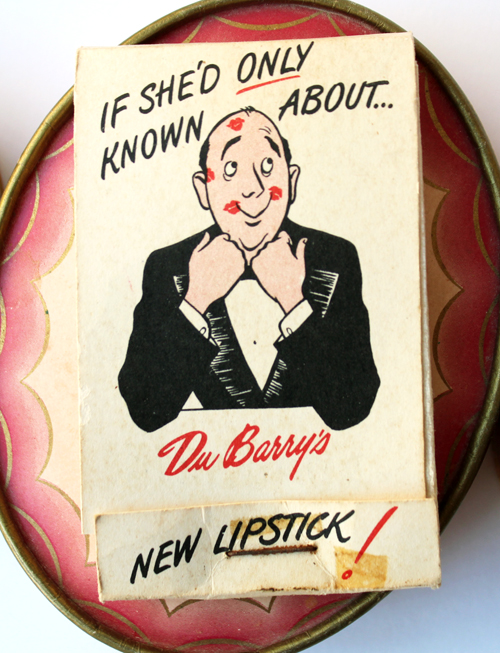

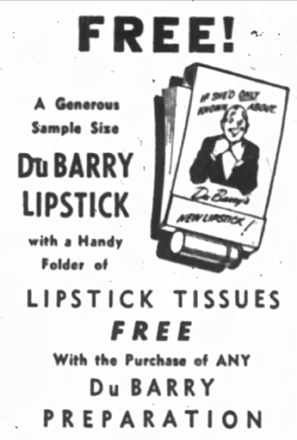

Of course, cosmetics companies also made their own lipstick tissues.

(image from etsy.com)

(image from etsy.com)

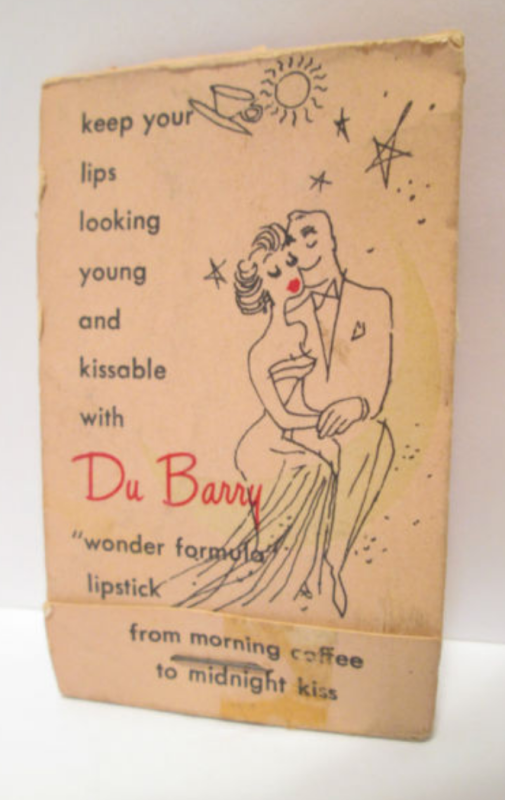

I was very close to buying these given how cute the graphics are, but didn’t want to spend $20. (I think they’re now reduced to $12.99, if you’d like to treat yourself.)

(image from ebay.com)

(image from ebay.com)

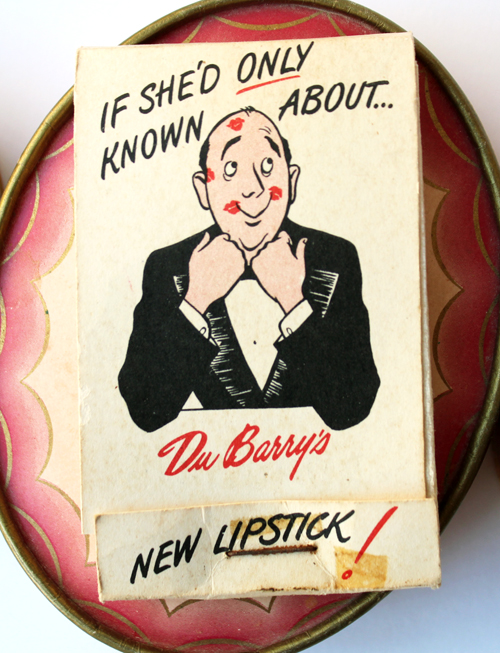

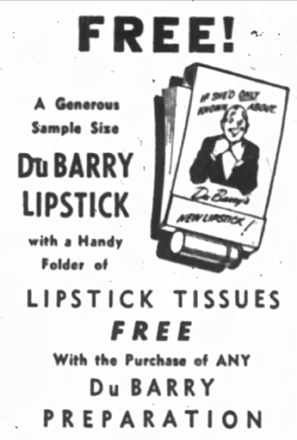

Plus, I already have these DuBarry tissues in the collection.

Funny side note: I actually found a newspaper ad for these very same tissues! It was dated July 27, 1948, which means the approximate dates I included in my DuBarry post were accurate.

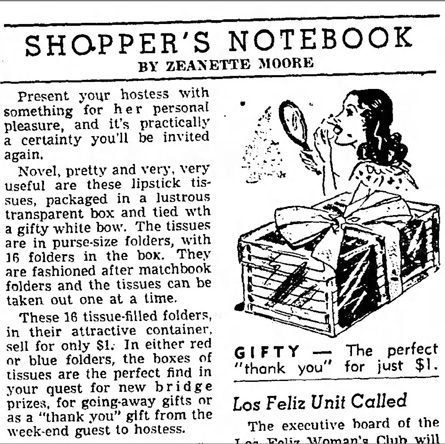

By the late ’40s, lipstick tissues had transcended handbags and became popular favors for various social occasions, appearing at country club dinner tables to weddings and everything in between. I’m guessing this is due to the fact that custom colors and monogramming were now available to individual customers rather than being limited to businesses.

“Bride-elect”? Seriously?

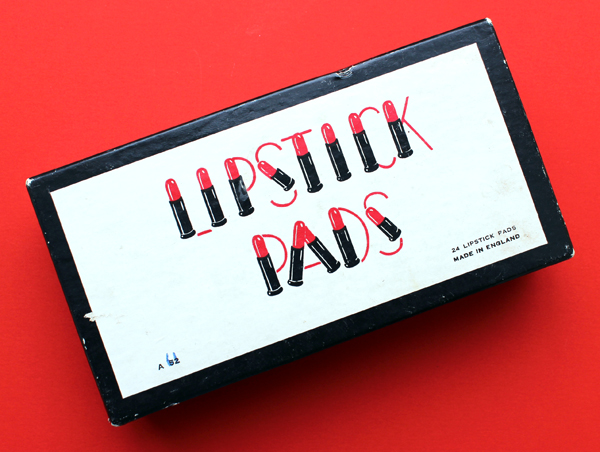

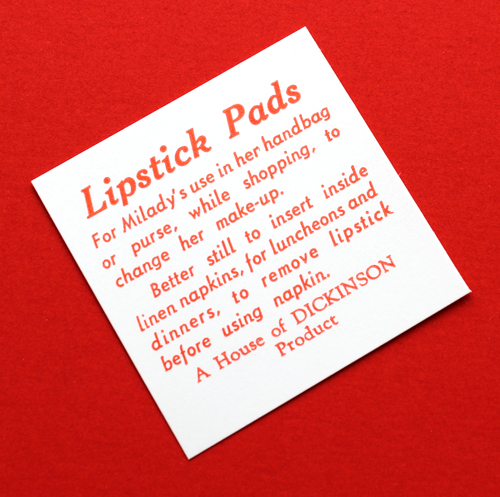

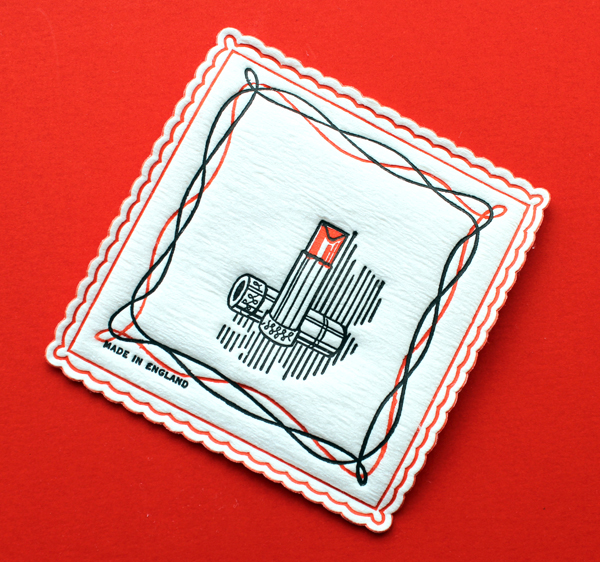

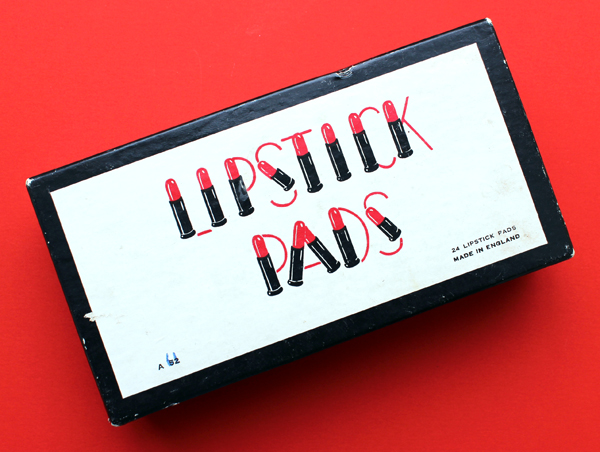

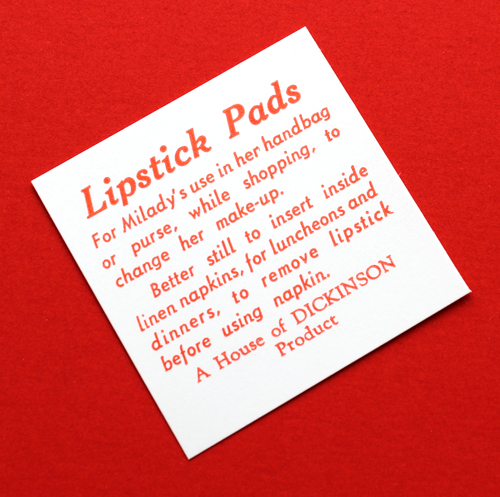

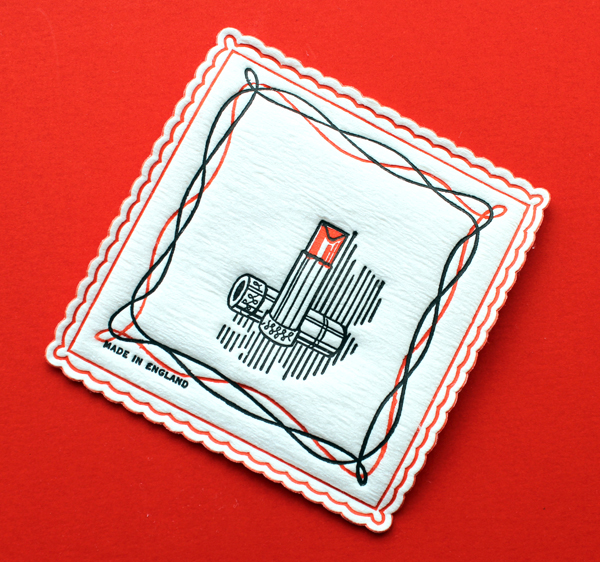

While the matchbook-sized lipstick tissues are certainly quaint, if you wanted something even fancier to remove your lipstick, lipstick pads were the way to go. These are much larger and thicker than Kleenex and came imprinted with lovely designs and sturdy outer box. This was the item that made me investigate lipstick tissues. I mean, look at those letters! I was powerless against their charm.

I couldn’t find anything on House of Dickinson, but boy did they make some luxe lipstick pads.

This design is so wonderful, I’d almost feel bad using these. If I were alive back then I’d probably go digging through my purse to find the standard Kleenex ones.

I also couldn’t really date these too well. There’s a nearly identical box by House of Dickinson on Ebay and the description for that dates them to the ’60s, which makes sense given the illustration of the woman’s face and the rounded lipstick bullet – both look early ’60s to my eye.

However, the use of “Milady” and the beveled shape of the lipstick bullet, both of which were more common in the ’30s and ’40s, make me think the ones I have are earlier.

By the mid-late ’60s, it seems lipstick tissues had gone out of favor. The latest reference I found in newspapers dates to November 1963, and incidentally, in cartoon form.

I’m not sure what caused lipstick tissues to fall by the wayside. It could be that there were more lightweight lipstick formulas on the market at that point, which may not have stained linens and towels as easily as their “indelible” predecessors – these lipsticks managed to easily transfer from the lips but still remained difficult to remove from cloth. Along those lines, the downfall of lipstick tissues could also be attributed to the rise of sheer, shiny lip glosses that didn’t leave much pigment behind.

While these make the most sense, some deeper, more political and economic reasons may be considered as well. Perhaps lipstick tissues came to be viewed as too stuffy and hoity-toity for most and started to lose their appeal. My mother pointed out that lipstick tissues seemed to be a rich people’s (or at least, an upper-middle class) thing – the type of woman who needed to carry these in her handbag on the reg was clearly attending a lot of fancy soirees, posh restaurants and country club dinners. This priceless clipping from 1940 also hints at the idea of lipstick tissues as a sort of wealth indicator, what with the mention of antique table tops and maids.

Lipstick tissues were possibly directed mostly at older, well-to-do “ladies who lunch”, and a younger generation couldn’t afford to or simply wasn’t interested in engaging in such formal social practices as removing one’s lipstick on special tissues. Plus, I’m guessing the companies that used lipstick tissues to advertise labored under the impression that most women were able to stay home and not work. With a husband to provide financially, women could devote their full attention to the household so advertising bread recipes and dry cleaning made sense. This train of thought leads me, naturally, to feminism: as with the waning popularity of ornate lipstick holders, perhaps the liberated woman perceived lipstick tissues as too fussy – a working woman needed to pare down her beauty routine and maybe didn’t even wear lipstick at all. Lipstick tissues are objectively superfluous no matter what brainwashing Kleenex was attempting to achieve through their marketing, so streamlining one’s makeup regimen meant skipping items like lipstick tissues. Similarly, after reading Betty Friedan’s 1963 landmark feminist screed The Feminine Mystique, perhaps many women stopped buying lipstick tissues when they realized they had bigger fish to fry than worrying about ruining their linens. Then again, one could be concerned about women’s role in society AND be mindful of lipstick stains; the two aren’t mutually exclusive. And the beauty industry continued to flourish throughout feminism’s second wave and is still thriving today, lipstick tissues or not, so I guess feminism was not a key reason behind the end of the tissues’ reign. I really don’t have a good answer as to why lipstick tissues disappeared while equally needless beauty items stuck around or continue to be invented (looking at you, brush cleansers). And I’m not sure how extra lipstick tissues really are, as many makeup artists still recommend blotting one’s lipstick to remove any excess to help it last longer and prevent feathering or transferring to your teeth.

In any case, I kind of wish lipstick tissue booklets were still produced, especially if they came in pretty designs. Sure, makeup remover wipes get the job done, but they’re so…inelegant compared to what we’ve seen. One hack is to use regular facial blotting sheets, since texture-wise they’re better for blotting than tissues and some even have nice packaging, so they’re sort of comparable to old-school lipstick tissues. Still, there’s something very appealing about using a highly specific, if unnecessary cosmetics accessory. I’m not saying we should bring back advertising tie-ins to domestic chores or the social stigma attached to not “properly” removing one’s lipstick on tissues, but I do like the idea of sheets made just for blotting lipstick, solely for the enjoyment of it. I view it like I do scented setting sprays – while I don’t think they do much for my makeup’s longevity, there’s something very pleasing about something, like, say, MAC Fruity Juicy spray, which is coconut scented and comes in a bottle decorated with a cheerful tropical fruit arrangement. As I always say, it’s the little things. They might be frivolous and short-lived, but any makeup-related item that gives me even a little bit of joy is worth it. I could see a company like Lipstick Queen or Bite Beauty partnering with an artist to create interesting lipstick tissue packets. Indeed, this post has left me wondering why no companies are seizing on this opportunity for profit.

Should lipstick tissues be revived or should they stay in the past? Why do you think they’re not made anymore? Would you use them? I mean just for fun, of course – completely ignore the outdated notion that one is a boorish degenerate with no manners if they choose to wipe their lips on a towel, as those Kleenex ads would have you believe. 😉

Save

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).