I'm still a bit wiped out from the spring exhibition and it's been ages since I've shared some inquiries that made their way in the ol' Makeup Museum Mailbag, so here's a quick review of some questions that have been sent my way.

First up is this lovely compact with a six-pointed star in blue rhinestones – perhaps a Star of David? – and matching lipstick, submitted from a reader in Australia. Her grandmother's brother had brought it back to her grandmother during the second World War. Without any logo or brand markings I can't pinpoint the company that made it, and after looking online and through all my collector's guides I can say I've never seen a vintage compact with this design. Obviously it was made in France, but I'm not quite as familiar with objects across the pond, as it were. It's a beautiful set and I wonder whether it has any wartime or Holocaust significance.

The second inquiry I have to share today was another head-scratcher. Someone had messaged me on Facebook (which I set up earlier this year but rarely use) asking about this little lady. It's a Revlon Couturine lipstick, but her identity remains a mystery.

As I've noted previously, allegedly the Couturines were supposed to be modeled after actresses and other purveyors of style. But this one doesn't seem to match any of the ones that have been identified. The only other actress whose name I've seen mentioned is Shirley MacLaine but it's not her either, according to this photo.

(image from worthpoint.com)

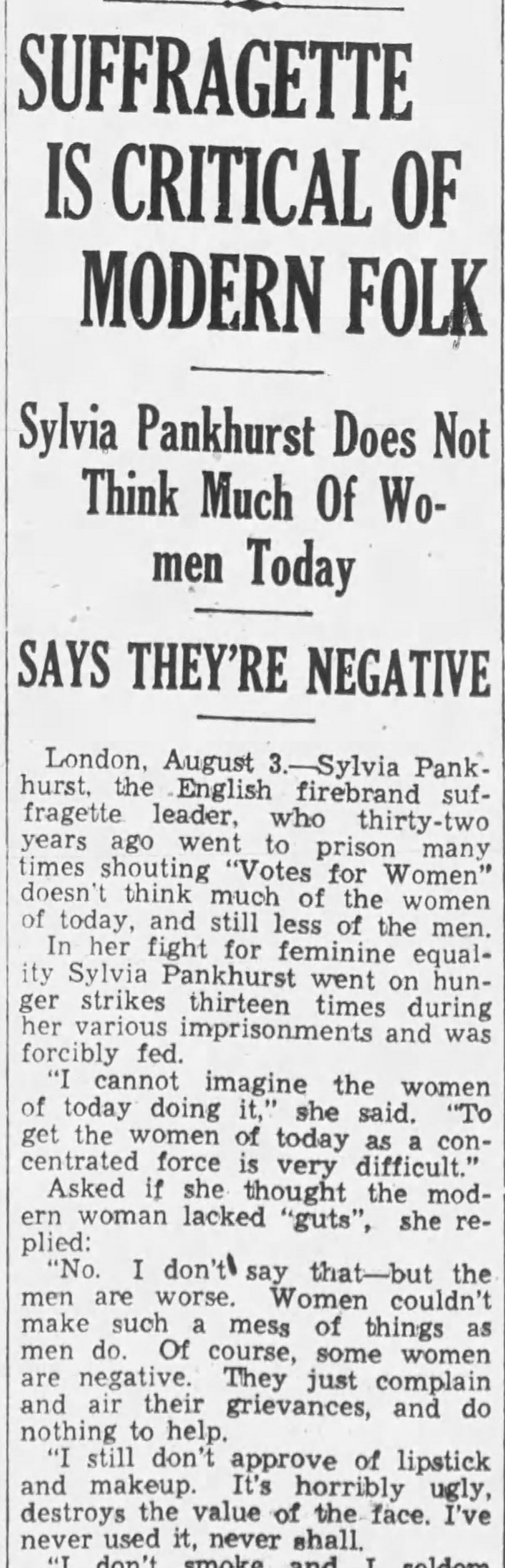

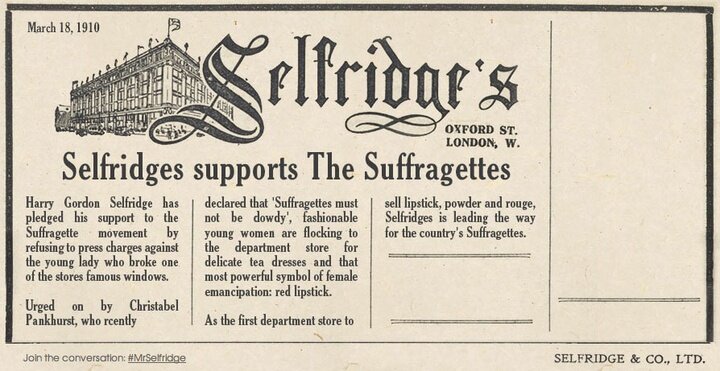

Finally, I received an inquiry from someone asking for proof that suffragettes wore lipstick as a symbol of emancipation. I swiftly directed this person Lucy Jane Santos's excellent article outlining how there really is no solid evidence that the ladies fighting for equality in the early 1900s regularly wore lipstick to rallies, or at least, to the big one in 1912. As she outlines in her article, it appears to be a persistent myth that most likely began circulating in the '90s both in Jessica Pallingston's book and Kate de Castelbajac's The Face of the Century: 100 Years of Makeup and Style (1995). Just for kicks and giggles I took a peek at newspaper archives (I'm finding they're just as fun and informative as magazines) and dug up a couple of interviews with British suffrage leader Emmeline Pankhurst and a profile of her daughter Sylvia. Their views on makeup are positively fascinating! As it turns out, Emmeline had no moral issue with cosmetics, she just didn't find a made-up face aesthetically pleasing: "Don’t think I am actually censoring the young girls nowadays…the very brief skirts and the overdone makeup are by no means an indication of loose morals. They are, in often rather a pitiful way, an indication of groping toward greater freedom and they are still more a groping towards beauty…the impulse to make one's self look as well as possible is a perfectly sound impulse. It has its root in self-respect. It is quite wrong to think that the use of short skirts and rouge are based on any violent desire to attract the opposite sex. The use of these aids [is] based on the legitimate desire to look one’s best. A woman dresses more for other women than for men. But the too-red lips and the extremely short skirt – I must confess that I dislike them. I dislike them because so few girls look well thus arrayed, and because older women, when thus arrayed, usually look rather ridiculous. But let me point out one fine fact behind all this makeup. It is not added with any idea of deception. The woman today who powders and paints does it frankly, often in public without one iota of hypocrisy. And this, I think, is a splendid gain.” (emphasis mine)

Her daughter, Sylvia, on the other hand, did not approve of makeup at all. "I still don't approve of lipstick and makeup. It's horribly ugly, destroys the value of the face. I've never used it, never shall." Her obituary also states that she thought makeup and lipstick were "tomfooleries".

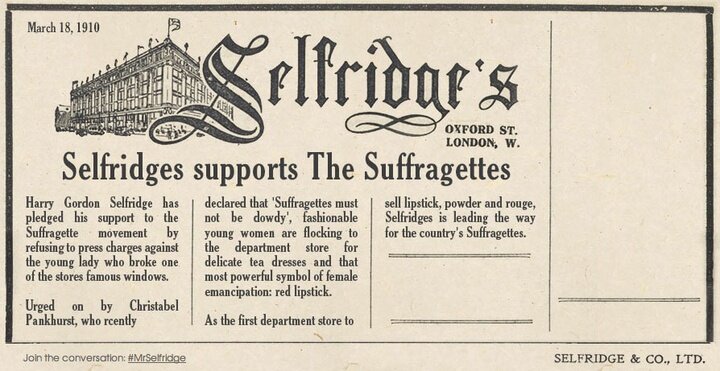

I did also see this 1910 ad from Selfridge's. This is what I believe to be the only reference to suffragettes wearing lipstick. I'm wondering if this is part of how the myth was generated, since even with this ad there doesn't seem to be any concrete proof that suffragettes wore lipstick. Selfridge's advertised and sold it; whether it was widely worn by suffragettes is still up for debate in my very humble opinion.

(image from @selfridges)

(image from @selfridges)

If you have any additional information about the things I've shared today, please let me know! Which one do you find most interesting?

As you know, from time to time I receive email inquiries from people with cosmetics objects they've stumbled across and would like to know more about. I'm always flattered that people think that I know what I'm talking about and can help them, especially since most of the time I have no idea about the item in question, but sometimes I get irritated when the inquirer's sole objective is to determine how much money they can make off an object they found. At first it seemed this way when the original owner of this very rare compact approached me, asking for more information and how much it might be worth. As we'll see, he turned out to actually have an interest in the compact's history and wasn't after profit.

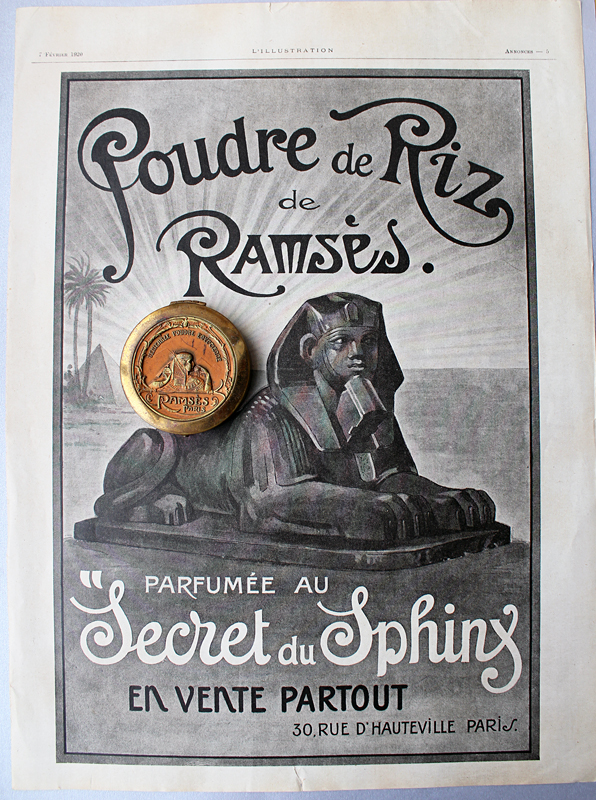

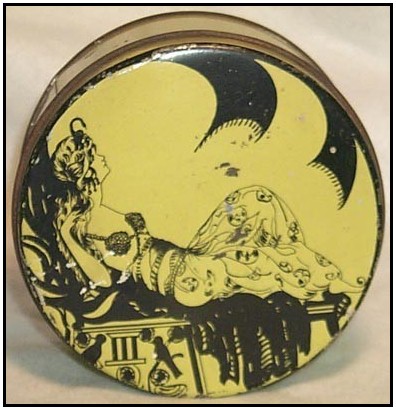

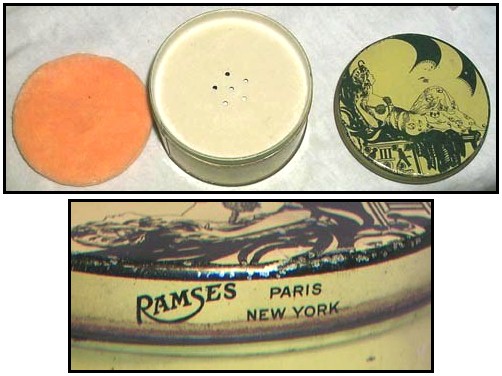

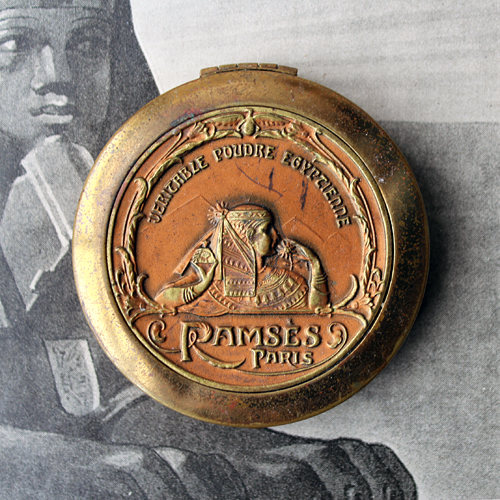

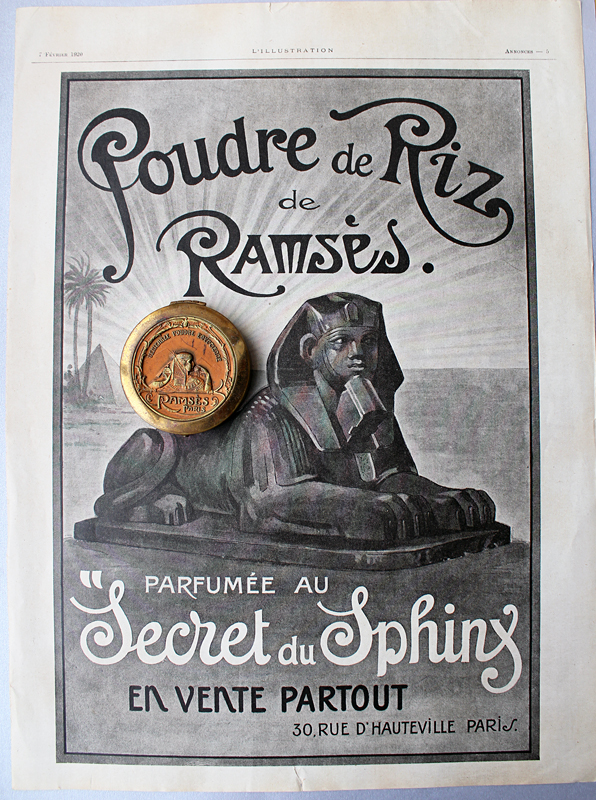

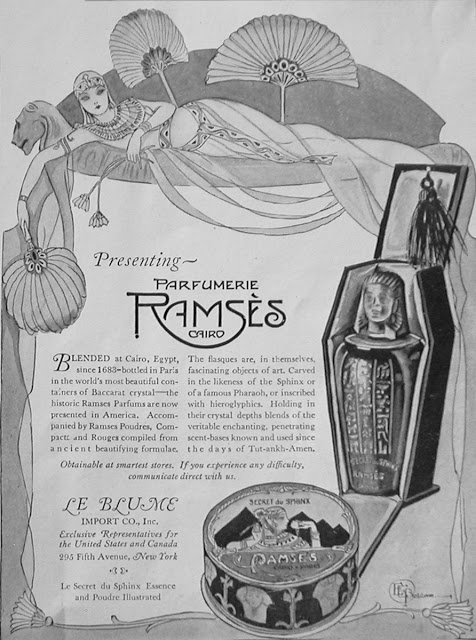

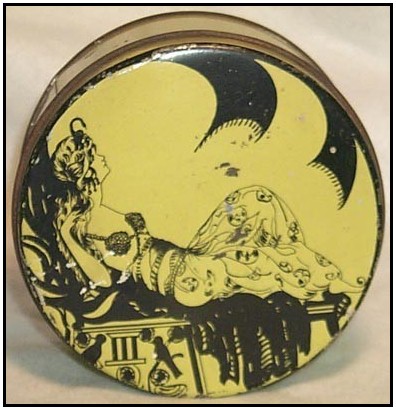

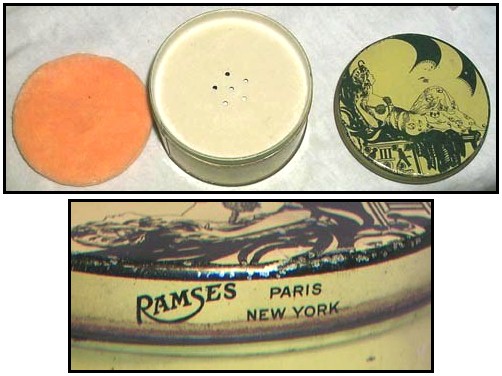

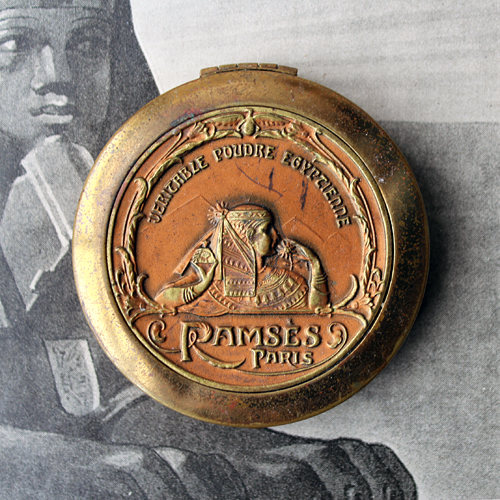

This was an epic find indeed, easily one of the rarest and most valuable in the Museum's collection. I now present the Ramses powder compact, which debuted in 1923. The design shows an Egyptian woman in profile, holding a perfume bottle in one hand and a flower in the other, which she brings to her nose to enjoy its scent. The pyramids of Giza are just barely visible in the background, while lotus flowers on each side towards the lower third of the compact bloom into an arc of leaves.

I'm not sure if the woman is supposed to be anyone in particular – perhaps Cleopatra – but given that the design is most likely not historically accurate, I'm not going to dwell on it too much.

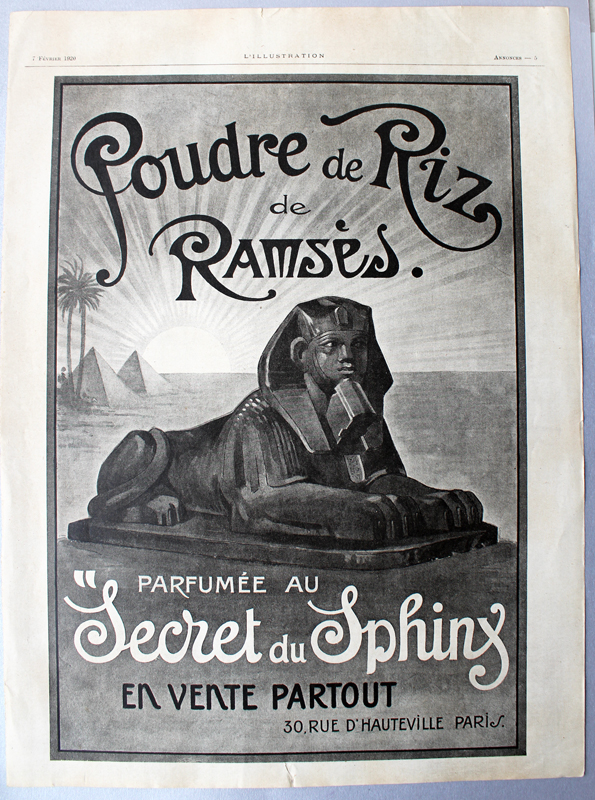

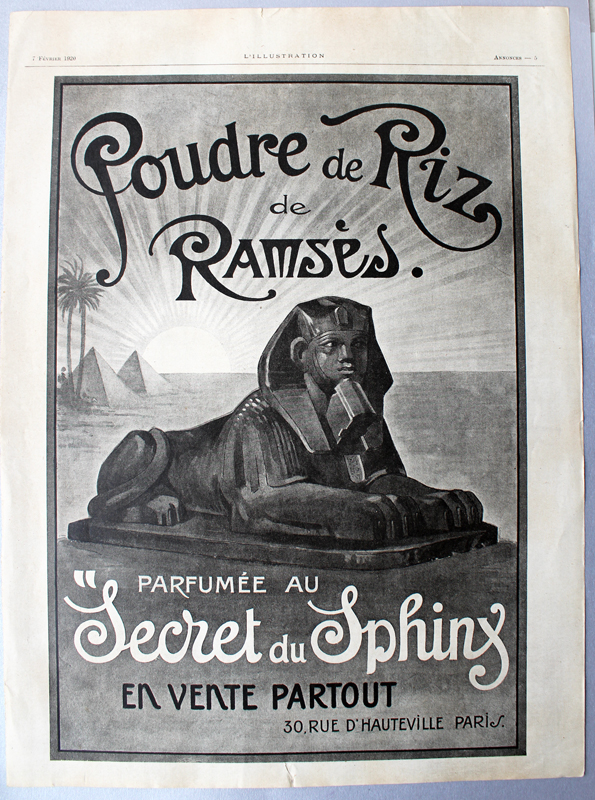

While there are other ads for the powder that show the compact, which we'll see in a second, I wasn't able to locate any originals. I did, however, find this ad in a French publication from February 1920.

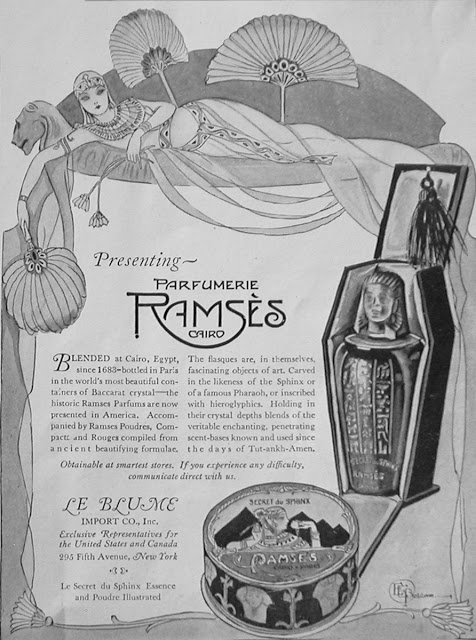

I was hoping to find some good information about the compact for the person who contacted me, and of course, the ever-thorough Collecting Vintage Compacts blog had an excellent post on the history of the Ramses perfume company so I directed the inquirer over there. I don't wish to regurgitate all of the author's hard work on Ramses' backstory – I highly encourage you to check out the post for yourself – but I will provide the abridged version. The Ramses brand was founded in 1919 in Paris and selected Le Blume Import Company to distribute the line in the U.S. in 1921. By 1923 ads for the powder boxes and compacts were appearing in Vogue magazine. As Collecting Vintage Compacts points out, the ad copy is pure nonsense: neither the perfumes nor the powders were produced in Egypt and their formulas certainly did not date back to 1683. How the company even arrived at that arbitrary date is beyond me. However, with the discovery of King Tutankhamun's tomb in November 1922, the Ramses moniker turned out to be quite fortuitous given the ensuing craze for anything Egyptian – clearly the ads wanted to milk the fad for all it was worth. The world was now swept up in the latest wave of Egyptian Revival, a style that incorporated various elements of Egyptian art and culture and encompassed design, fashion and beauty (see this compact depicting Theda Bara as Cleopatra and this ad as examples).

Egypt's influence on Western beauty from the Renaissance to today is a subject I'm looking to cover more thoroughly this year, either in a blog series or an exhibition (or both!) so stay tuned. As viewed through 21st century eyes, it was clearly unabashed cultural appropriation, a white person's fantasy of "exotic", far-off lands and artifacts. However, Egyptian inspired-beauty is such a rich topic that I can't bear not to fully explore it…especially now that I have this gorgeous piece in my hot little hands. Anyway, Collecting Vintage Compacts notes that the Ramses powder case was made by the Bristol, CT-based Zinn Corporation, a company that produced some of the earliest and most memorable compacts in the U.S. I find it interesting that while the powder was scented with the "Secret du Sphinx" fragrance, the compact itself shows a woman rather than the mythical creature. Collecting Vintage Compacts speculates, as I did, that the woman could be Cleopatra, but offered the additional option of Ramses' wife Nefertari. I agree with his conclusion that it really doesn't matter who she is – just a vague Egyptian theme was more than enough to get the point across.

Another version of the compact sported silver edging, a beautiful contrast to the warmth of the brass.

(images from Collecting Vintage Compacts and Ruby Lane)

I also spotted some ads in newspapers. They're not as visually striking as the Vogue ads so I'm not including them here, but they did come in handy for indicating the original retail price of the compact, which was $1.00. The latest ads I could find were from 1925 and both the perfumes and powder were heavily discounted, which indicates Ramses was a flash in the pan.

But why? You would think given the era's craze for Egyptian-inspired design, combined with the slight French flavor (another huge selling point – this was a time when companies actively tried to give their lines and products authentic French or at least French-sounding names) the Ramses company would be able to get more a little more mileage out of their products. Collecting Vintage Compacts unraveled the mystery. As it turns out, the perfumer behind the Ramses brand, one Léon de Bertalot, had begun quite a shady scheme to sell another one of his fragrances. In 1914, 5 years before he launched Ramses, de Bertalot named one of his fragrances Origan. As we know, Coty's L'Origan (launched in 1909) was wildly popular, pulling in roughly $3 million in sales in 1921 alone. De Bertalot decided to capitalize on the company's success and began using the Coty name to sell his own Origan, essentially passing it off as a real Coty product. Coty, rightfully so, cracked down on this very quickly. On May 15th, 1923 a French court found de Bertalot guilty of "unfair competition", and a few days later the U.S. Treasury mandated that any inauthentic products bearing the Coty name were unable to be imported unless they specifically spelled out that they were not affiliated with Coty in any way. Since the Ramses brand had nothing to do with Coty I don't know if the Treasury's mandate applied to Ramses as well, but I'm sure the 6-month jail sentence and fine of 100,000 Francs handed to de Bertolot essentially meant the Ramses brand was out of business. Hence the price markdown of their products by 1925 – I'm guessing stores in the U.S. were trying to offload any leftover stock that was originally imported two years prior. The Le Blume Import Company, in turn, was no longer allowed to distribute any perfumes from any company whatsoever. However, it did import dusting powder tins and glass jars using the Ramses name in the late 1920s.

(images from Vanity Treasures and Etsy)

Getting back to the original inquiry that was the impetus for this post, here's the story of how the compact got into my hands from the person who emailed me originally (we'll call him C.) He had found it for $10 in a thrift store (!) but given the unique design, figured it was worth more. After looking through all my collector's guides and not turning up anything, I directed C. to Collecting Vintage Compacts and asked him to please let me know when/if he decided to put it on the market. Obviously I also indicated my great interest in obtaining the compact, but lamented that it was most likely out of my price range. Well, don't you know C. actually wrote back telling me that he was going to put it up for sale on Ebay, but said that while he'd like to get a good price for it (that's only fair, who wouldn't?), he believed that the Museum was the rightful place for the compact, given its rarity and my passion for lovingly researching and preserving these sorts of items. Thus he kindly offered to sell it to me directly and negotiate on price. In the end I think we both got a great deal – he got way more than what he had originally purchased it for and roughly the amount he would have gotten for it if he had put it up for public sale, and I got an amazing find at a fair price for which I was able to avoid an ugly bidding war.

After reading the Ramses history at Collecting Vintage Compacts and browsing the Museum's site, C. seemed genuinely interested in the compact and in the Museum's mission, so I was very happy to see he wasn't just in it for profit and was willing to work with me to ensure the compact went to a great home instead of merely to the highest bidder. :) I really appreciated it, as so many people who ask about value just want to know how much they can get for an item and have absolutely no consideration for the object's history or the Museum, which, as a reminder, is funded entirely out of my own pocket. Not that anyone is obligated to donate rare and valuable items, of course, but they could follow C.'s example and be open to selling their item to me at a price that works for both of us. I know if I came across an object I have no interest in but that other collectors might – say, a rare Barbie Doll – I'd seek out someone who would truly treasure it and give them first dibs.

What do you think? And yay or nay on a series/exhibition on Egyptian-inspired beauty?

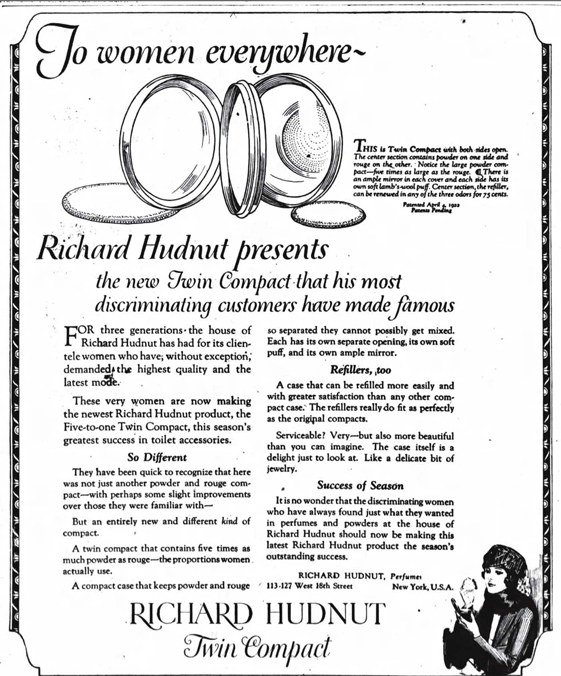

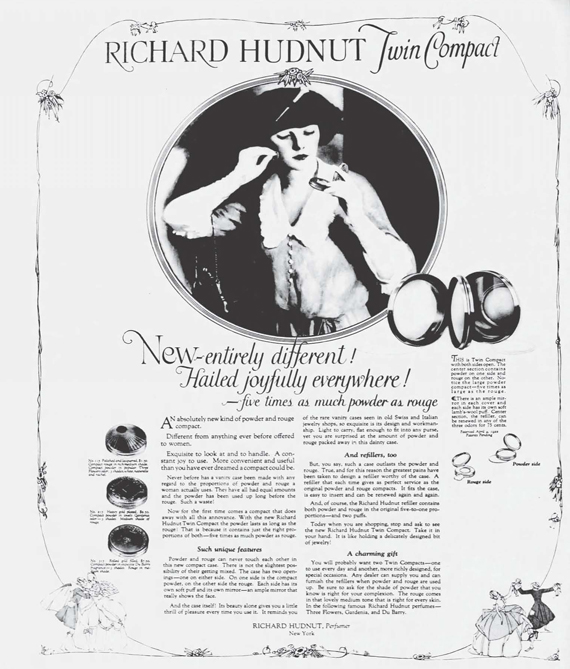

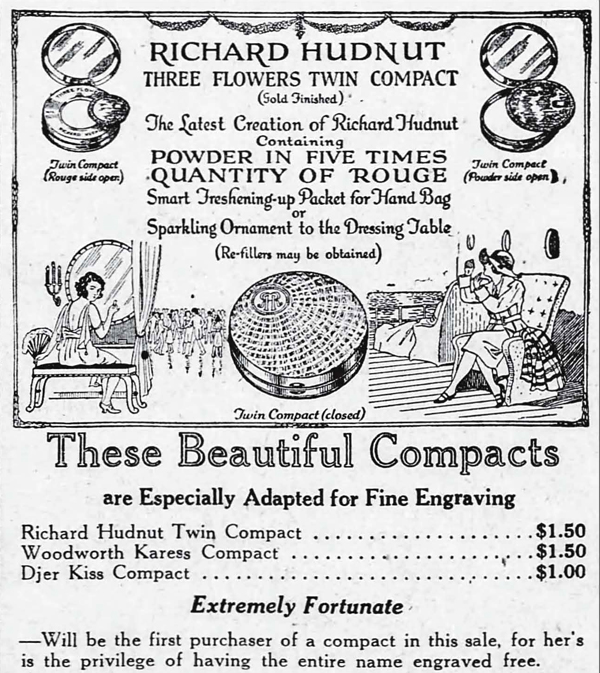

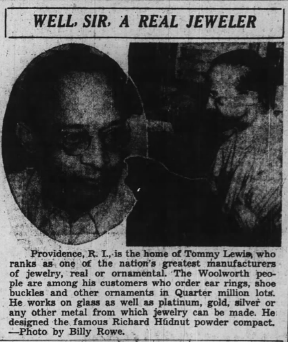

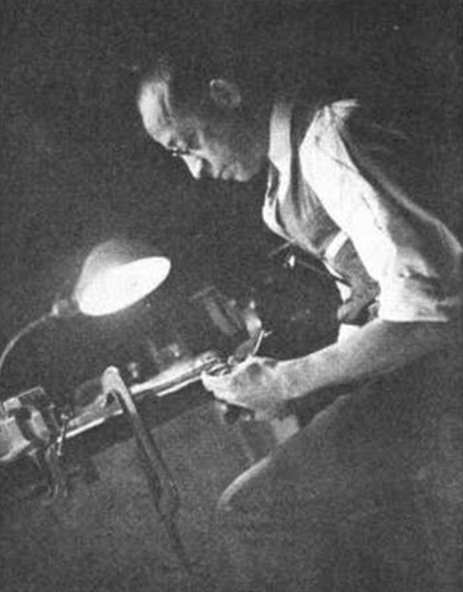

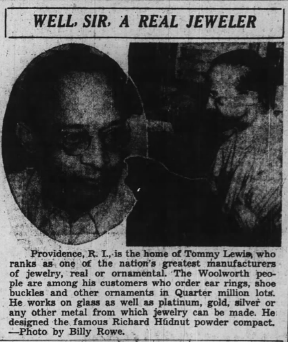

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

As usual, I forget exactly what I was searching for at newspapers.com when, about a month ago, I stumbled across a very interesting article from 1938. I know the search term must have included Richard Hudnut’s name, but beyond that I can’t remember. In any case I was delighted to uncover a profile of a rather remarkable man. Thomas R. “Tommy” Lewis apparently designed many of the compact cases for perfumer Richard Hudnut from possibly the mid-1920s through at least the ’30s. Both Collecting Vintage Compacts and Cosmetics and Skin have excellent histories of the brand, so you can check them out there. I, however, will be focusing on Lewis and some of the compacts he may have created. The reason why I felt such a compelling need to share his story is a matter of race: Lewis was one of very few American Black jewelers in his day, and one who overcame both racism and poverty to establish his own very successful jewelry firm. In honor of Black History Month I thought it would be appropriate to share as much information as I was able to find on Lewis, and hopefully I can do it without whitesplaining or tokenizing. I offer my sincere apologies in advance if I offend! (Constructive criticism is welcome; mean comments are not).

According to another article written in 1935 that I found online, Lewis was born into an impoverished family in Providence, Rhode Island. Undaunted by his circumstances and without the support of his parents or siblings, he attended RISD with the hopes of becoming a jeweler, earning a scholarship in the process. After graduating he worked for a leading jewelry manufacturer in Providence for several years, then struck out on his own.

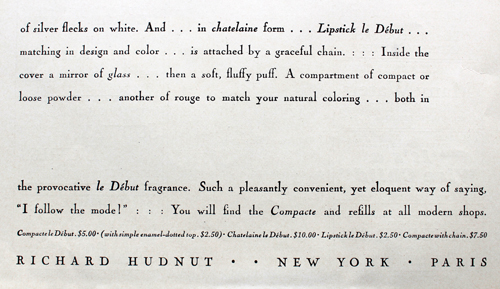

I was unable to find the date he started his company or much other information besides what was in these two articles. The 1935 online article says that he started his business 27 years prior, so I’m assuming he established it in 1908; however, the 1938 article says that he had been in business for 26 years, so maybe it was 1912. And there’s no information on his relationship with Hudnut other than what was in that article, so when he started making compacts for them is unclear. The only (rather patronizing) mention is as follows:1 “Visit the cosmetics department in any first class store, ask the clerk to show you a Richard Hudnut powder compact and then surprise him by telling him that he is looking at the work of a [Black] man. Everyone of those compacts was designed and produced here in a plant at 19 Calendar Street, the home of the Lewis Jewelry Manufacturing Firm. The same is true of their perfume bottles, for Mr. Lewis works on glass as well as platinum, gold, silver or any other metal from which jewelry or ornaments can be made. The Richard Hudnut people are among his biggest customers, but not his most consistent. That honor is reserved for other jewelry manufacturers who regularly send in their commissions for original designs in bracelets, watch chains and other novelty jewelry.” So it seems that while Hudnut was not the biggest source of business for Lewis’s company, we know that he was designing all of their compacts by 1938, and presumably earlier. When I purchased these compacts for the Museum I made sure to select ones that I could get specific dates for, i.e. compacts that were plausibly produced by Lewis given the approximate timeline, and also ones that seemed to be the most jewelry-inspired.

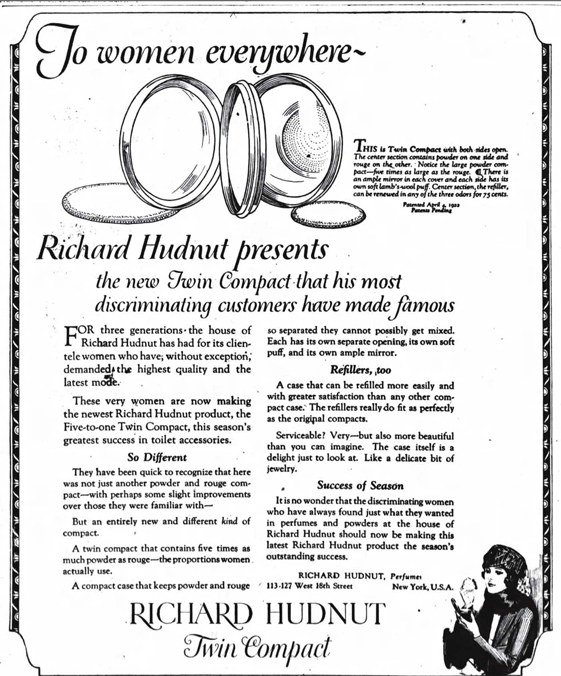

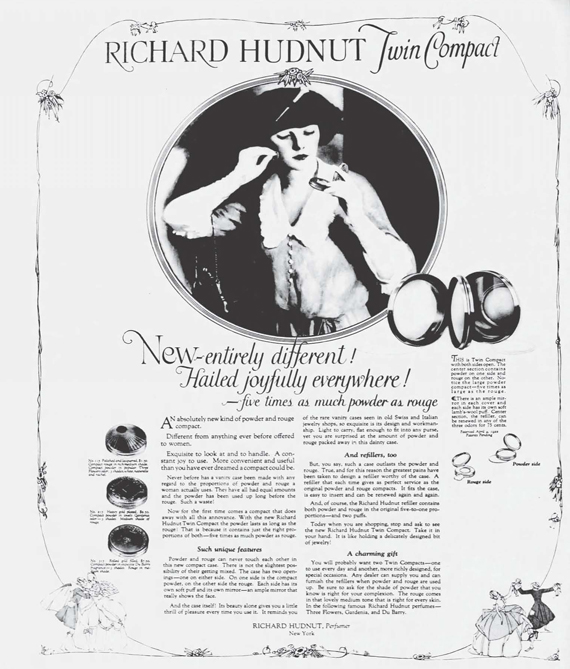

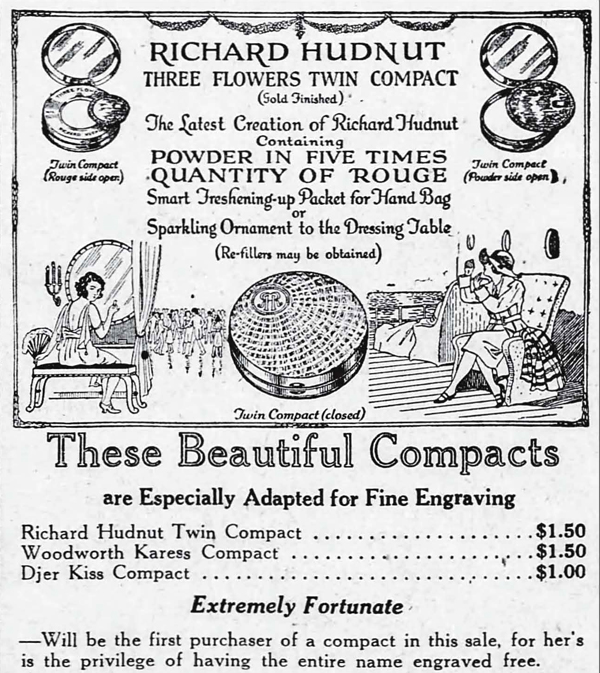

First up is the original “twin” compact, which was introduced in late 1922. I didn’t realize this until after I bought it, but this double case was designed by a man named Ralph Wilson in 1921 and patented in early 1922. Wilson was the New York representative for Theodore W. Foster and Bro. Company, a prominent compact and jewelry manufacturer. Foster, like Lewis, was also based in Providence, so maybe there might be some connection between this company and Lewis’s – perhaps this is the company Lewis worked for after graduating from RISD? In any case, we have proof that the twin compact was created by a company other than Lewis’s, so this is not his work. I still like to think, though, that Lewis may have apprenticed with Foster, grew familiar with Hudnut’s aesthetic and went on to earn the company’s favor over Foster.

How cool is this? You flip over the blush and there’s powder on the other side. Genius.

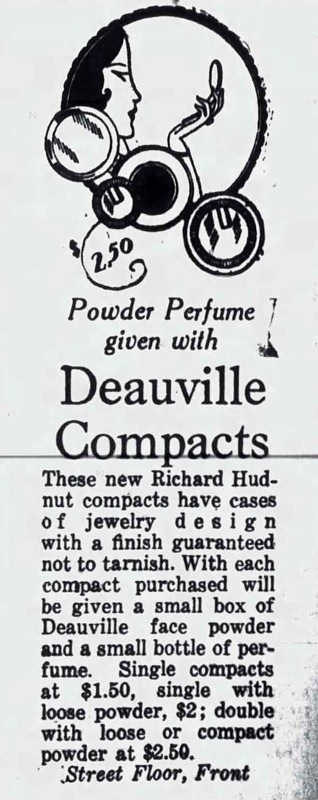

Hudnut’s Deauville fragrance was introduced in 1924. Again, no telling whether this was done by Lewis, but probably not given that it’s basically the same interior mechanism as the earlier twin compact.

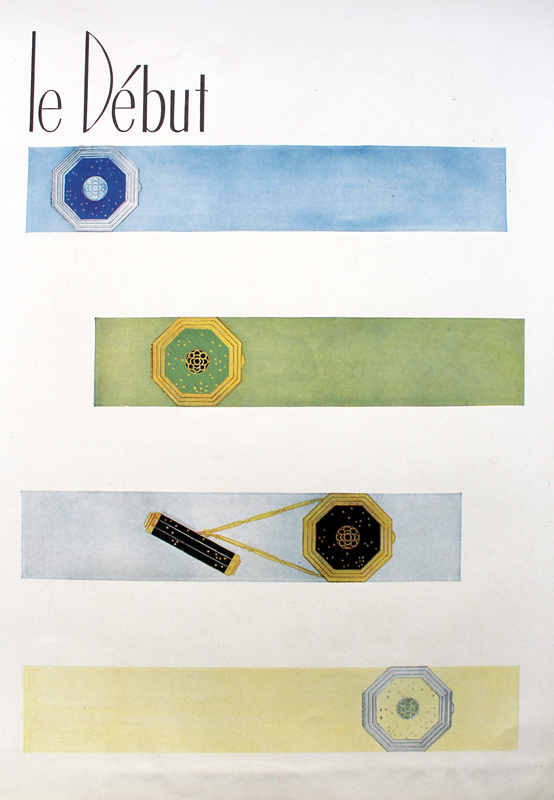

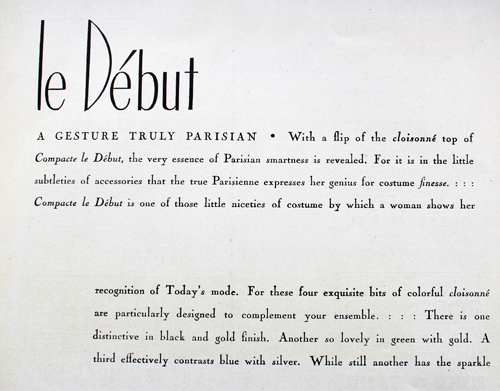

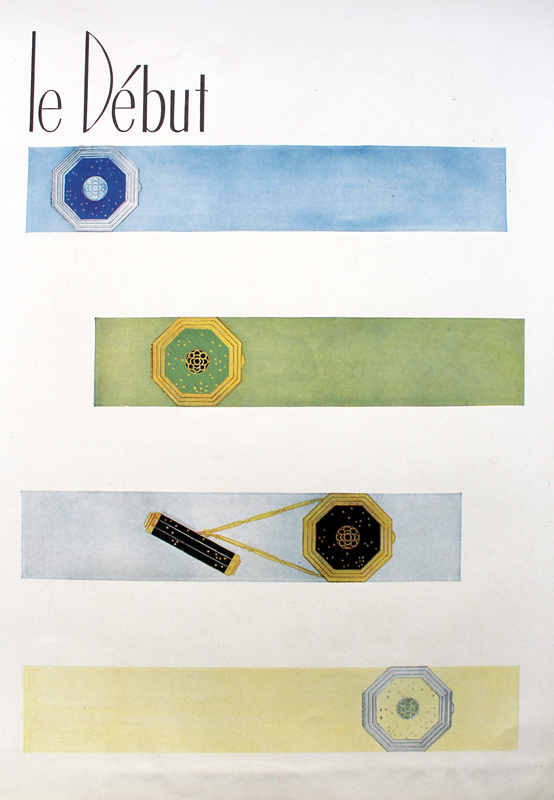

Le Début, a fragrance available in 5 different variants that were color-coordinated to their bottles and powder compacts, well, debuted in 1927. I was fortunate enough to track down an original ad for these beauties. They’re actually pretty common – I was able to find all the colors shown in the ad – but in the end I thought the black one was the most elegant. (Okay, I really love the silver one too!)

In the 1938 photo below it states that Lewis designed the “famous Richard Hudnut compact”, but I really have no idea which one they’re referring to. It could be Le Début, or it could be the “triple vanity” compacts designed in the mid ’30s.

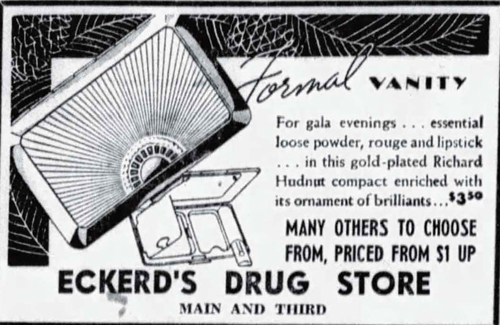

This enameled, oh-so-Deco case came out in 1936, according to the newspaper ads I found, and the last mention of it was in 1938. Again, it’s funny how certain objects call to you. This one was also available in a variety of colors, but I just knew the red belonged in the Museum.

The triple vanities had three compartments for powder, blush and lipstick.

The ad also mentions jewelry several times, so I’m hopeful it was made by Lewis’s hand.

Lastly, I picked up this stunner, which dates to about 1939. Evidently between this one, the Three Flowers compact and the silver Evans compacts I have a thing for sunburst patterns, probably because they remind me of glorious sunny days.

How exquisite is this jewel detail? And in such impeccable shape for a nearly 80 year-old compact – it’s mind-boggling that none of the stones are missing.

To give you a sense of how dainty and small these triple vanities are, here they are with one of NARS’ highlighting trios.

Getting back to Lewis, I can’t say for sure whether his company was responsible for any of these compacts; I can only hope at least some of these jewelry-inspired designs were his. The fact that the 1935 article doesn’t specifically mention Richard Hudnut makes me think that perhaps Lewis wasn’t designing compacts for Hudnut until somewhere between 1936-1938. But it’s also entirely possible he had been producing compacts for them for years. In any case, I want to highlight just how difficult it was for a Black man in the 1900s to not only get out of poverty, but graduate from one of the top design schools in the country AND start his own business that eventually employed up to 60 workers in the busy seasons. As the 1935 profile states: “But jeweler, designer, silversmith? What chance would he have? Where could he work? Who ever heard of a [Black] man, a designer, a master craftsman in the jewelry trade of all trades! One can imagine what would have been Lewis’s fate if his ambitions had been left in the hands of some of the so-called vocational guidance counselors who are at the present time shaping the lifework of many [Black] students in the public schools of our large cities. According to the formula which they use, there are no [Black] jewelers now in existence, hence no future; it would be impossible for a [Black] silversmith to get a job since he cannot belong to the union, and the white jewelers would not employ him anyhow.” Through incredibly hard work and innate talent, Lewis persevered, not only becoming a success himself but also helping others do the same. Most of his employees were Black, and Lewis provided them with better wages than other jewelry firms in Providence as well as training.

I just wish I could have found more information and photos to make for a somewhat complete biography. Searching online for Lewis’s company yielded nothing, as did basic searches for Lewis himself. I ended up contacting the Rhode Island Historical Society and they kindly provided census records indicating his year of birth (1880), but said they didn’t have any business records related to Lewis’s company, which I think is bizarre. If it was as prolific as the articles claim it was, and if it really did provide hundreds of thousands of pieces of costume jewelry to the likes of Saks and Woolworth’s and compacts for Hudnut, I find it very strange that there are absolutely zero traces of his company left save for these two profiles. Especially since the 1938 article even gives the address of his workshop – with that specific type of information there should be historic maps or architectural records listing it. He also apparently had over 200 patents to his name, none of which I was able to find. I guess the saddest part is that there are tons of other stories like Lewis’s, and we simply don’t hear about them. So many histories for non-white people are erased or buried, and I really wanted to bring Lewis’s story to the surface because it was truly outstanding (and not only because it’s Black History Month…I just so happened to find the newspaper article around a month ago and thought the timing worked out nicely). I really hope this post didn’t come across as patronizing or me highlighting a “token” Black person.2 I find Lewis’s story impressive not because I can’t believe a Black man could ever be creative and intelligent enough to start a jewelry firm, but because of all he had to overcome to achieve his goals. “Perhaps it is the memory of a [Black] boy with a dream to become a jeweler, a silversmith, a designer, a [Black] boy who kept his dream despite the doubts of his family from within and racial prejudice from without. For Thomas Lewis is an artist and so he believes in young men and young women with dreams.”

Thoughts?

Update, 11/24/2022: One of the Museum’s Instagram followers alerted me to a video made by a vintage compact collector who mentioned Tommy Lewis while showing some of her Hudnut collection. It got me thinking whether anything else on Lewis had been discovered and lo and behold, two students from Rhode Island College were able to unearth some more information, including a map showing where his store and factory were! While it didn’t shed any light on Lewis’s relationship with the Hudnut company, their article surely adds more to this important piece of history. Lewis was born on April 5, 1880 and graduated from RISD in 1902. In 1925 a lacquer explosion caused a fire at Lewis’s shop located at 171 Eddy Street, which damaged much of the building. I’m wondering if some of the early business records were lost in that fire. Throughout his life, in addition to providing training and employment for Black workers, he was a philanthropist and active in the YMCA and other community organizations. Lewis passed away in 1958. I can only hope someone writes a full biography of this exceptionally talented man, but in the meantime sure to check out the article at rhodetour.org. Oh, and they even included the Makeup Museum’s original article as a “related resource”. I’m so honored!

1 I spent several hours googling whether it was acceptable to type the word “c*lored” if I was quoting from an old newspaper article. In the end I realized I personally didn’t feel comfortable using it even if it was a quote, so I replaced it with “black”.

2 I rarely, if ever, highlight makeup histories featuring people of color, i.e. Madam C.J. Walker, Annie Turnbo Malone, etc. because I’m not sure whether it’s okay for a white person to do that – while I think their stories absolutely need to be heard and recorded, once again I fear that it would come off as whitesplaining or tokenizing if I attempted to write about them. In the case of Tommy Lewis, there was such scant information available I’d figure I’d make an exception in order to at least introduce him and his work.

Save

Save

Save

Save

It's the most wonderful time of the year…to look at vintage Christmas makeup ads, that is! You know I can't get enough of these, so here's a quick roundup (in no particular order) of some I added to the Museum's collection this year. 🙂

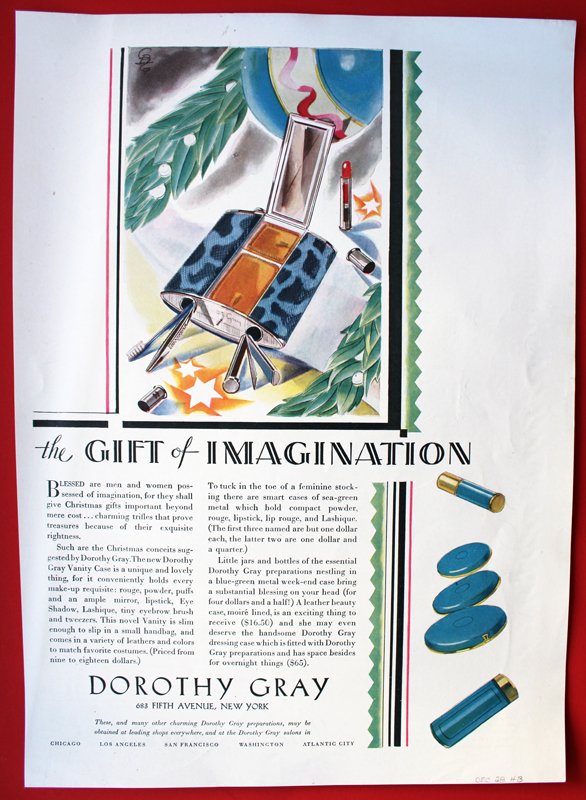

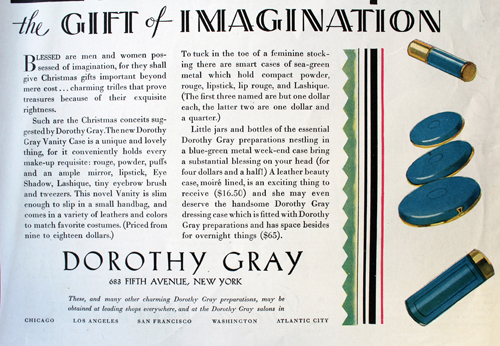

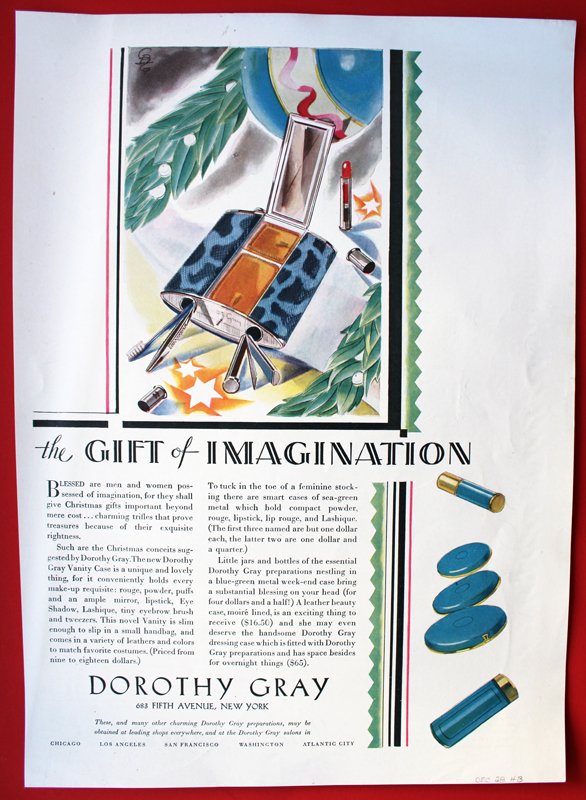

I have many Dorothy Gray ads, but not any from the '20s. Their early packaging was so sleek.

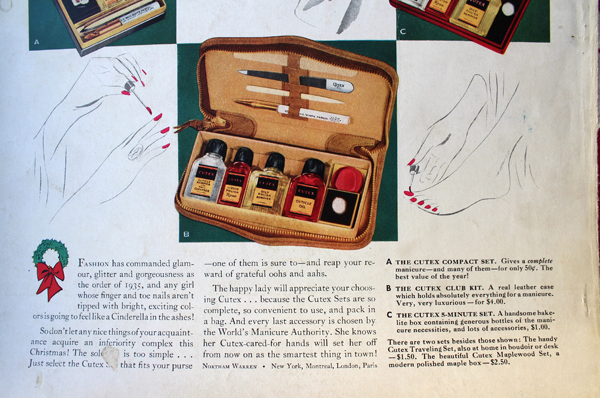

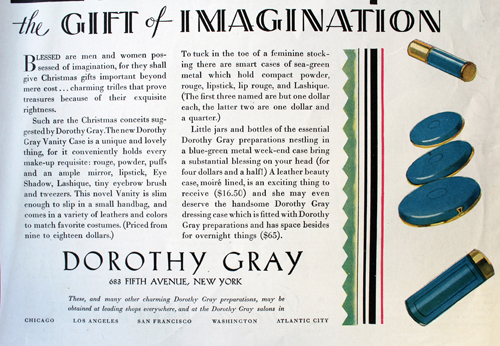

Apparently you can avoid an inferiority complex with a manicure set. LOL.

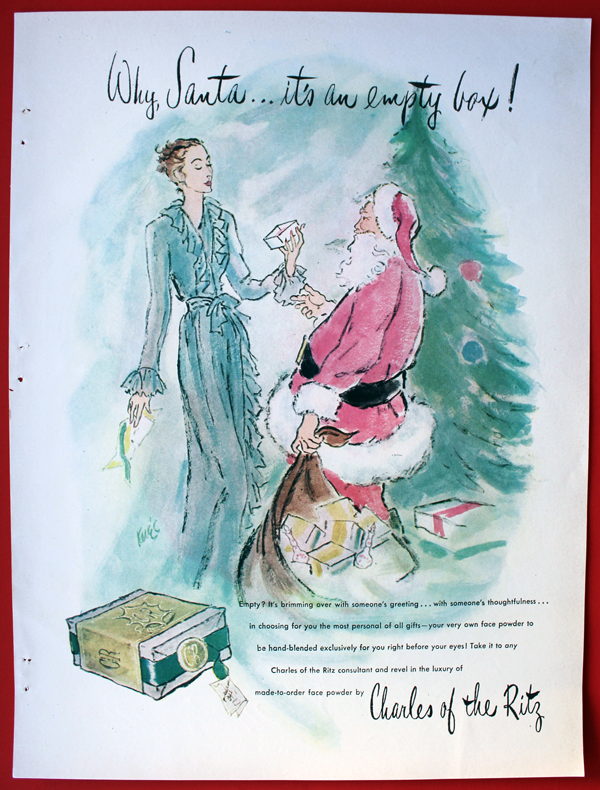

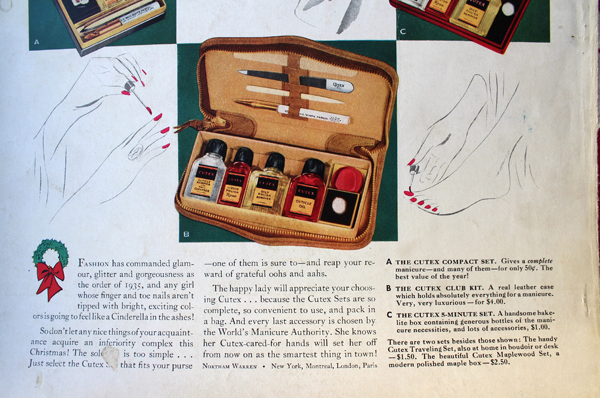

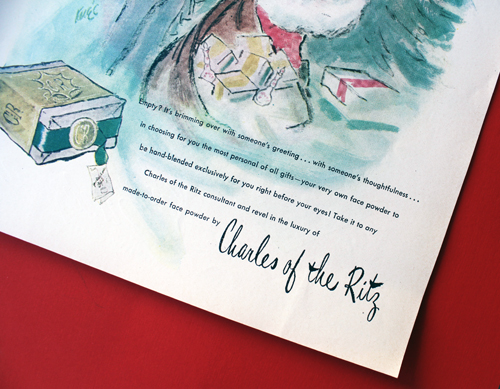

Santa, you jerk! Why did you give me an empty box? Now I have to go to the store and have it filled?! That's not a good present!

I understand custom powder was Charles of the Ritz's bread and butter and you had to actually go to a counter to get your own personal blend, but I'd still be pissed if someone gave me this. Get me a nice compact!

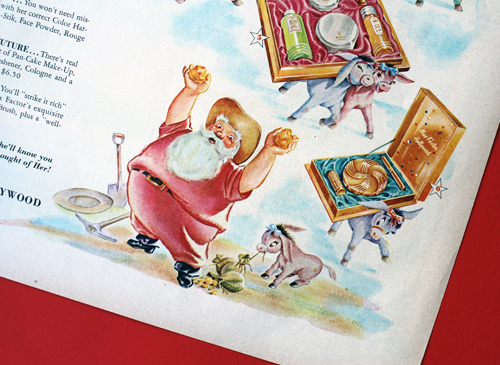

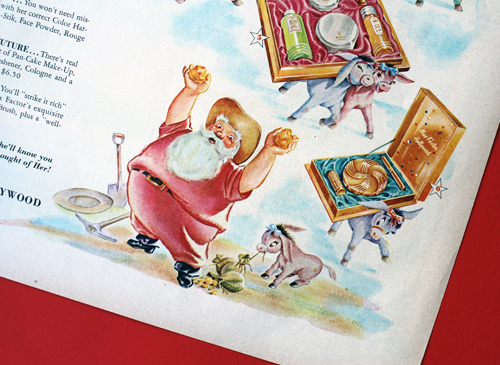

Santa gave considerably better gifts in this ad. I'm a bit confused about the presence of donkeys (shouldn't it be reindeer?), but I do love the overall cartoon-y look of this one.

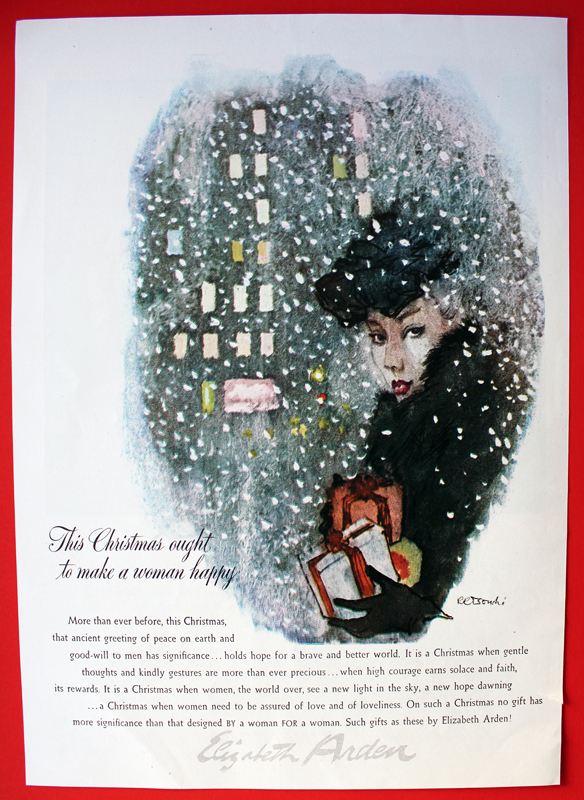

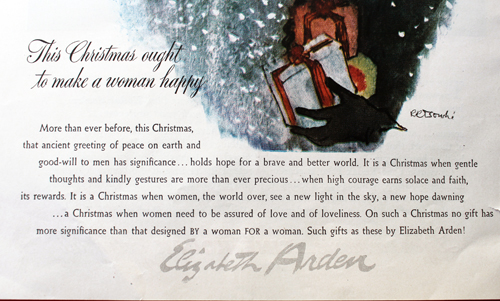

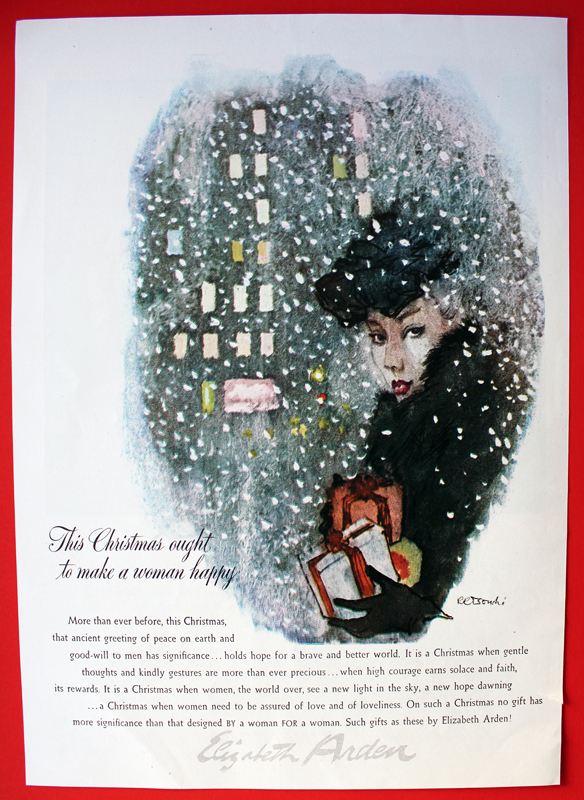

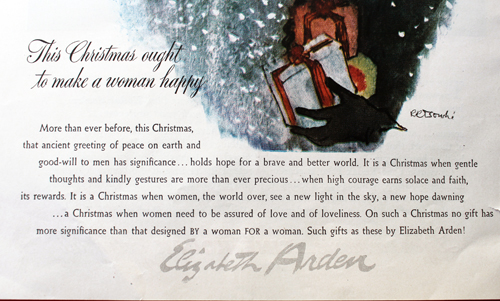

René Bouché (1905-1963) was Elizabeth Arden's head advertising illustrator in addition to working for Vogue. If you see an illustrated ad for Elizabeth Arden from the 40s or 50s most likely it was done by Bouché's hand. I believe this is the first ad by this artist to join the Museum's collection. 🙂

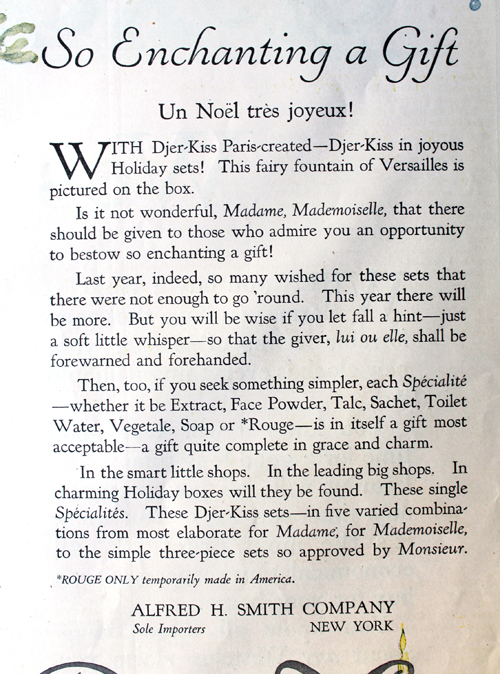

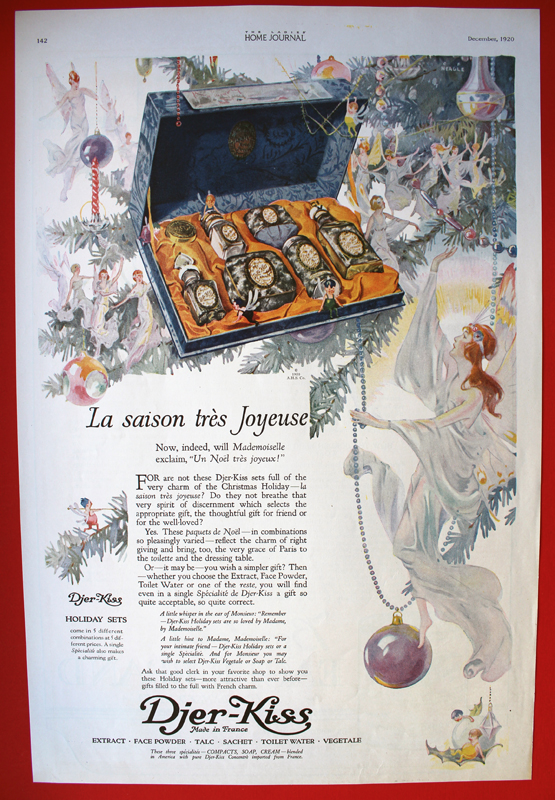

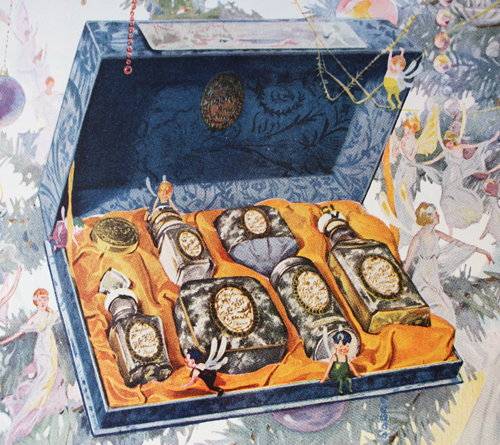

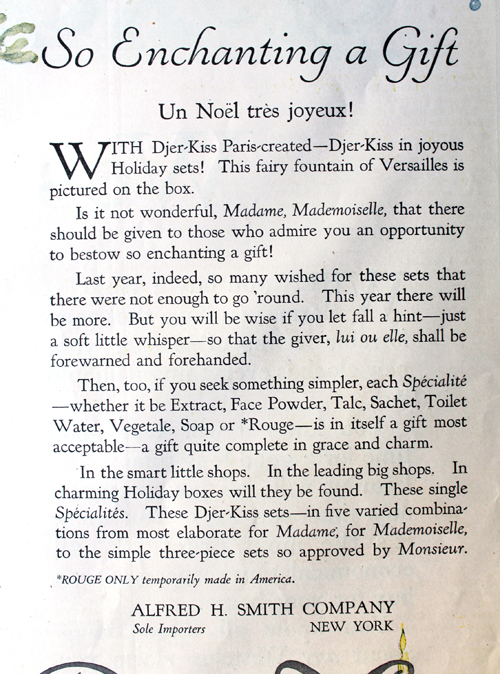

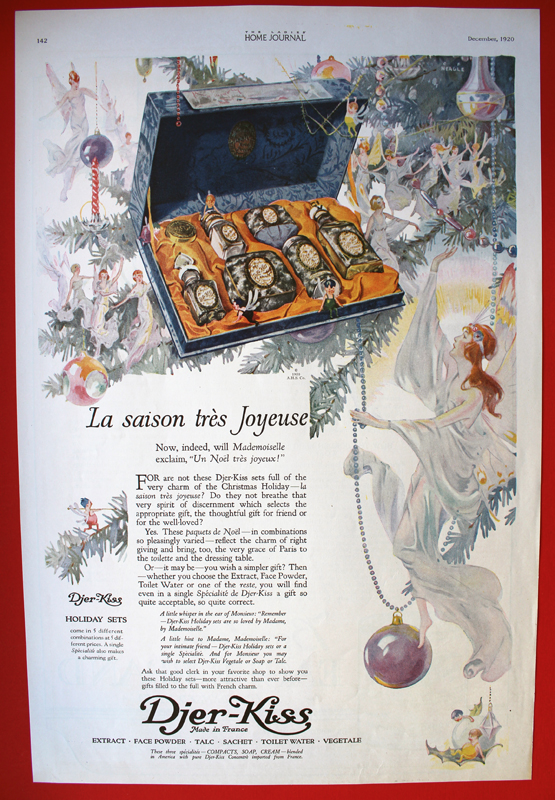

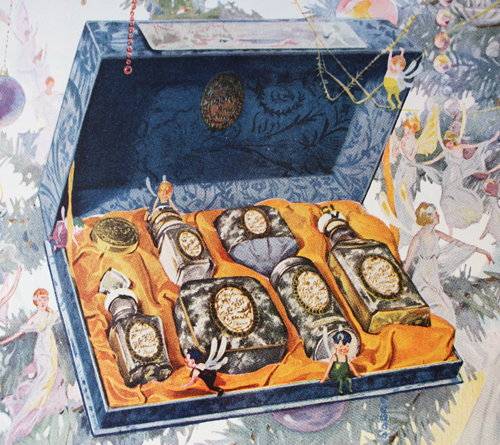

I can't recall how I stumbled across these Djer-Kiss ads, but I'm so pleased I found them! Djer-Kiss "Kissing Fairies" compact has been on my wishlist for a long time, but the ads are just as gorgeous as the compacts. I'm hell-bent on collecting all of them, as they're simply beautiful and feature a variety of illustrators. Collecting Vintage Compacts has an amazingly thorough history of the company, which makes me want them all the more. I believe the illustrator for this one was Willy Pogany, although I couldn't find a signature anywhere so I can't be sure.

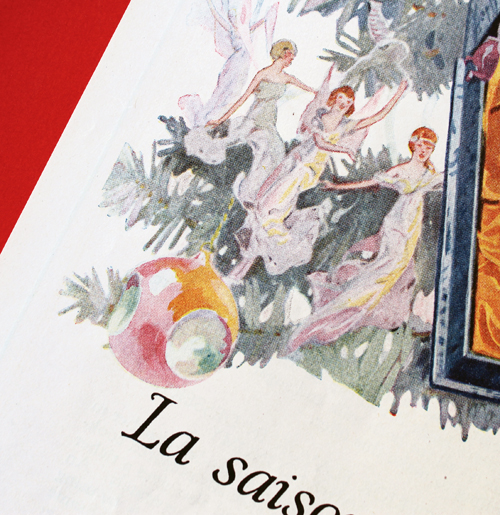

This one is by C.F. Neagle, who does a breathtaking job of capturing iridescence – from fairy wings to Christmas baubles, there's a multi-colored sheen that seems to pop off the page.

I love all the little sprites flitting about the gift box, particularly the ones hanging off the top and sitting on the edge. Incredibly charming, no?

So that concludes 2017's vintage Christmas ad roundup! Which one was your favorite? I love all of these, of course, but I'm partial to the very silly Max Factor ad and the beautiful Djer-Kiss ads.

(image from @selfridges)

(image from @selfridges)