Content warning: mention of suicide in the 3rd to last paragraph.

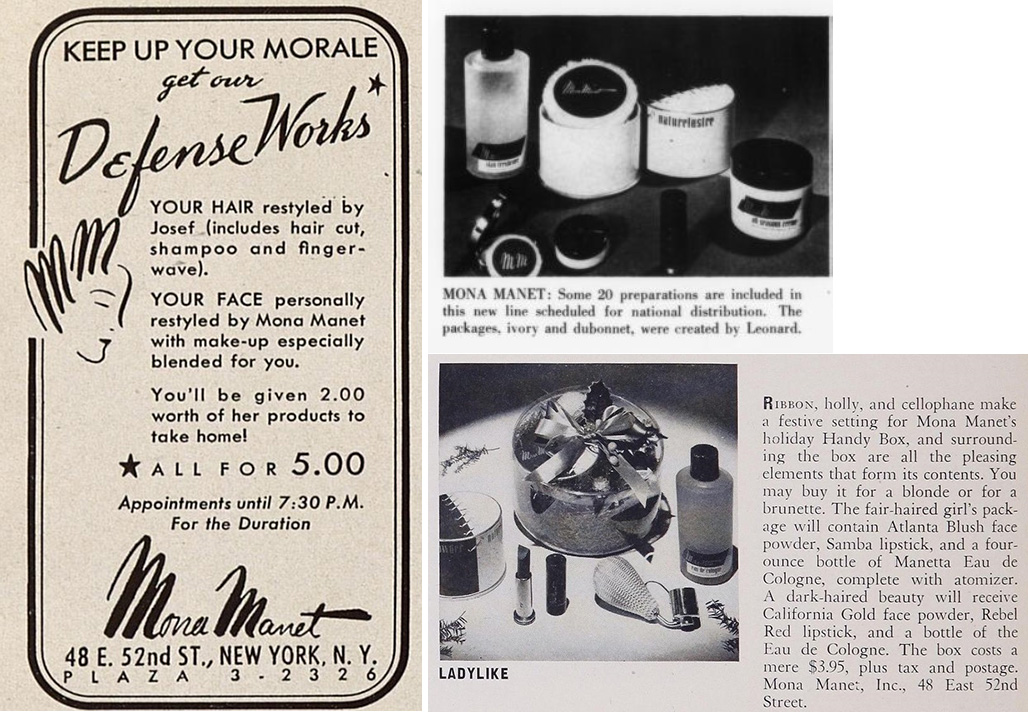

I wish I was sharing something uplifting instead of tragic, but I wanted to discuss a very talented writer who contributed much to the beauty industry during her short life. Mona Manet debuted her eponymous line of cosmetics in 1941 in her New York City salon. Soon the brand rolled out nationwide, and Manet enjoyed a brief career as a salon owner, makeup artist and beauty columnist. However, she was harboring a big secret: while Mona Manet presented herself as white, she was in fact a Black woman who had adopted a new identity and a new name to go with it.

Mona Manet was born as Elsie Roxborough in Detroit, MI, in 1914 into a prominent Black family. Her father Charles was a Detroit College of Law graduate who owned a weekly paper, the Detroit Guardian, and also served as a state senator. Her biracial mother, Cassandra, sadly died while delivering Elsie’s younger sister, Virginia, in 1917. Roxborough was the first Black woman to live in the dorms at the University of Michigan, largely due to her father’s efforts to fight discrimination on campus. However, it was not without struggle. Roxborough was alienated by most of her fellow Black students, who perceived her cultured upbringing as snobbish. But she was not fully accepted by whites either. Says Kathleen Hauke, who wrote a thorough profile of Roxborough in 1984 for the Michigan Quarterly Review: “Her [wealth] produced a tension between Roxborough and other blacks on campus who had not enjoyed her privileges. To white students she was an exotic, not like other Negroes yet not like themselves either.” Being rejected by both races was perhaps one of many reasons for Roxborough’s decision to live as a white woman.

(image from the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan)

Despite these obstacles, Roxborough’s gift for writing flourished. She wrote for the campus paper alongside classmate Arthur Miller and established a theater troupe, the Roxane Players, for whom she wrote her own plays. In 1937 she worked with Langston Hughes to produce his play Drums of Haiti. She and Hughes began a professional relationship/friendship. In his autobiography, Hughes remembers, “Elsie would tell me about her dreams, and wonder whether or not it would be better for her to pass as white to achieve them. From what I knew of the American entertainment field and how [Blacks] were almost entirely excluded from the directorial or technical aspects of it, I agreed with her that it was difficult for any [Black] person to gain entrance except as a performer…and for a [Black] woman I think it would be even more difficult than a man. Elsie was often mistaken for white in public places, so it would be no trouble at all for her to pass as white. While I was in Spain she wrote me that she had made up her mind to do so. She intended to cease being [Black].” The meteoric rise of boxer Joe Louis, whose was managed by Roxborough’s uncle John, was perhaps the last straw for her in terms of living as a Black woman and the impetus for pursuing a career in beauty. Hauke suggests, “The rejection of her plays by critics and judges contrasted with the nearly incredible success of Uncle John’s golden boy. If making it as a Black in America demanded masculine brute strength, she would flee to the genteel white world in which a woman’s arts would be appreciated.” Roxborough dyed her hair from black to auburn and moved to California, taking the name Pat Rico and working as a model. After less than a year on the West coast she relocated again, this time to New York City. It’s not clear exactly when she adopted the Mona Manet name, but most likely it was around late 1939-early 1940.* It’s also unclear as to when she opened her salon at 48 East 52nd St, but it seems that is where she got her start in beauty. Over the next decade Roxborough would manage her salon, release a cosmetics line, write for a number of publications and serve as makeup artist to models and actresses for various fashion shows, press events and theatrical productions.

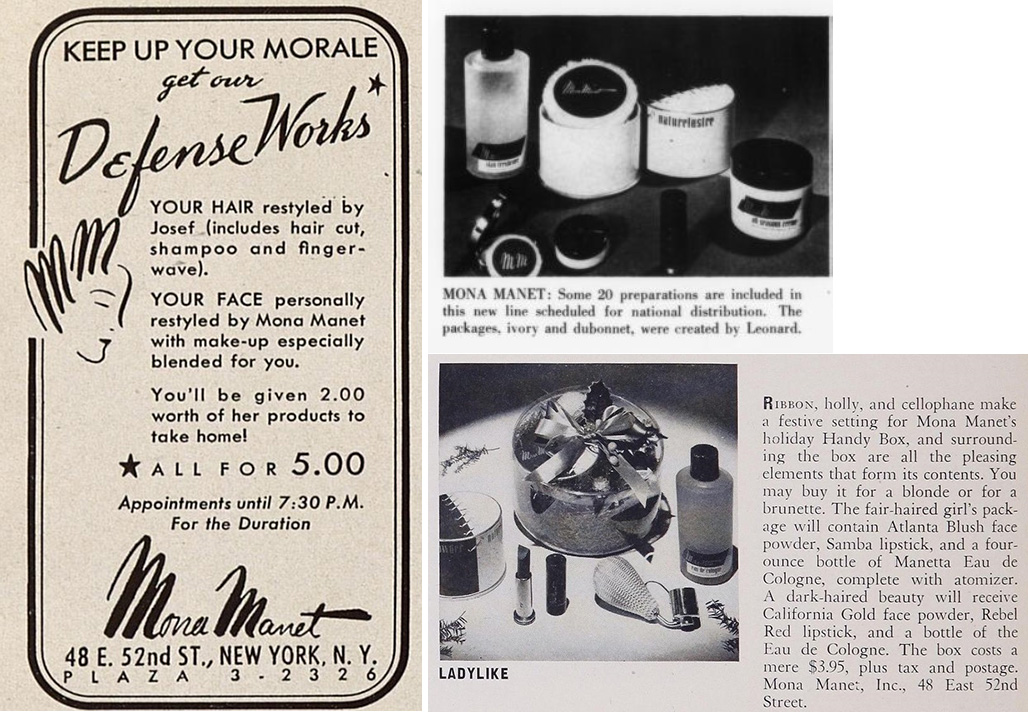

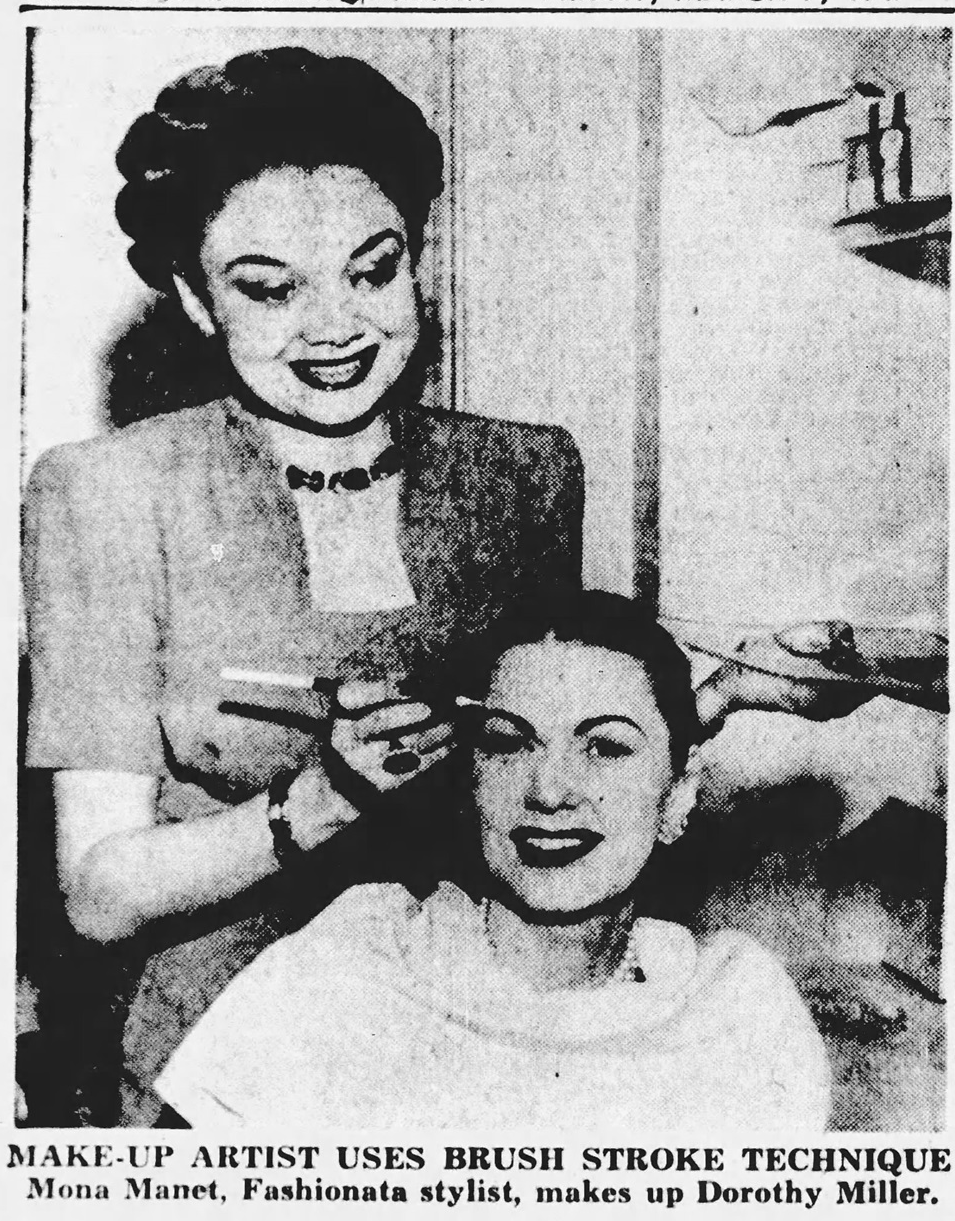

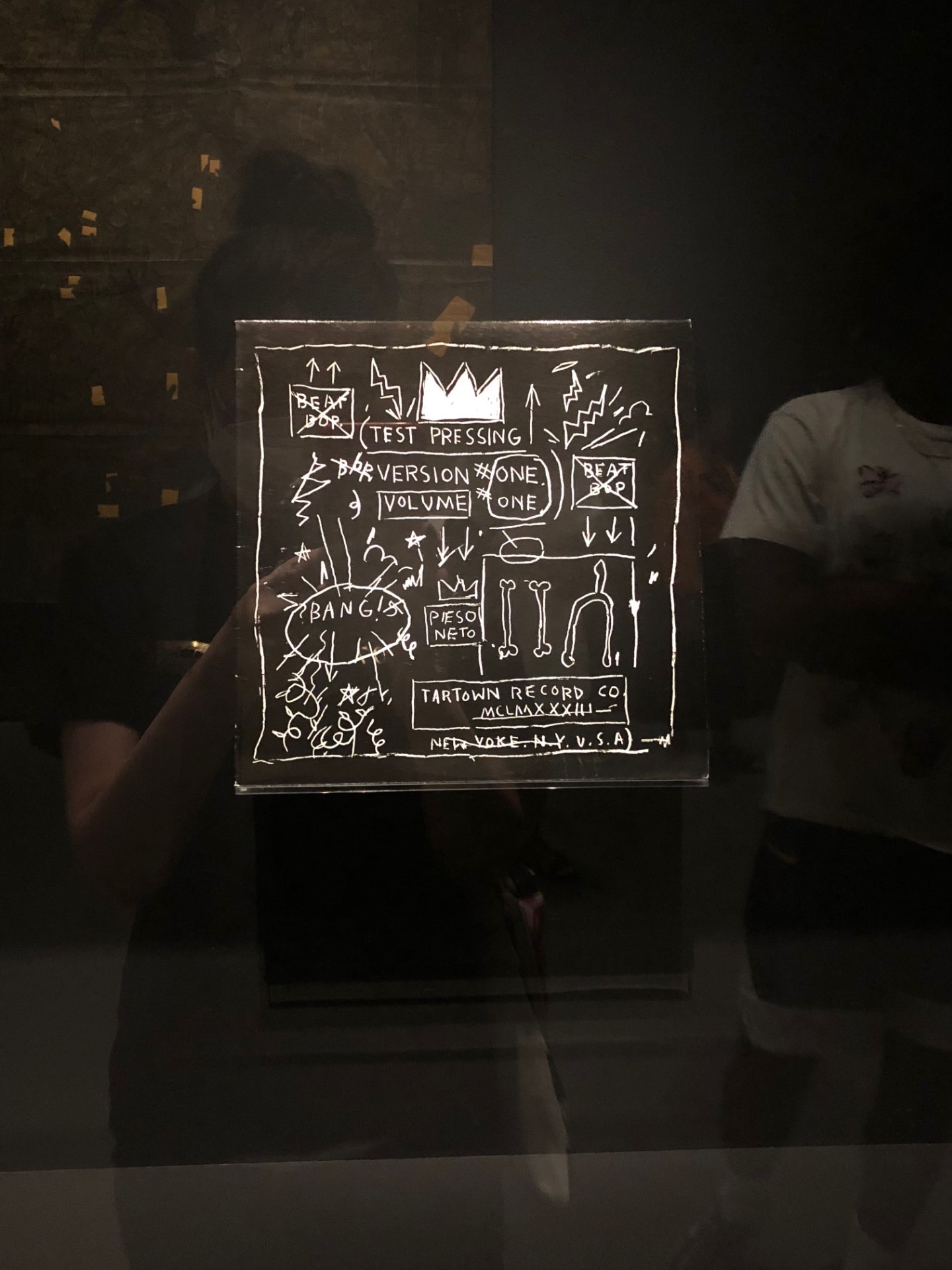

In February 1941 several trade publications reported on the Mona Manet cosmetics line, which was distributed nationwide later that year.

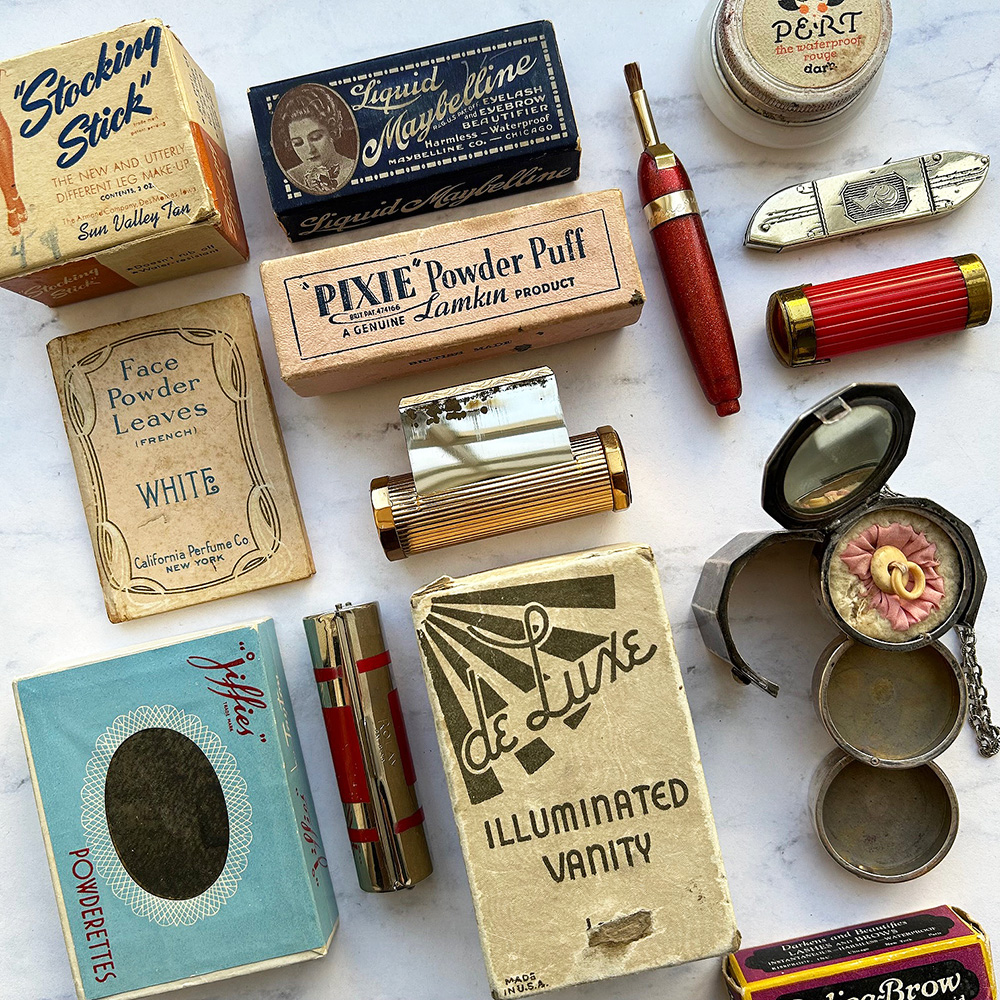

It was the packaging that caused me to purchase the lipstick and rouge on eBay. I knew absolutely nothing about Elsie Roxborough or Mona Manet, but the font of the signature was intriguing. At first glance the style appears somewhat ‘80s, but the bakelite packaging and size made me realize it had to be ‘30s or ‘40s. The lipstick is the shade Samba and the rouge is Rebel Red.

Here’s an eyeshadow which for some reason slipped by my radar. I will be forever heartbroken over not adding it to the Museum’s collection. Update, March 2025: As I was packing up the Museum’s collection to move to new headquarters, I found the eyeshadow!! Apparently I had purchased it and it somehow got separated from the rouge and lipstick.

The violet eyeshadow was part of the Mona Manet “duration” makeup collection, which she originally used on the Ziegfeld Follies girls. Meant to be a delicate, feminine contrast to “severe uniforms” of women in the military and worn for the duration of the war, the collection consisted of the following: “a new orchid-pink shade, a baby-blue eyeshadow for use over the lids with a violet shadow graduating towards the brows, along with an ethereal face powder over all.” The rouge and lipstick were appropriately named “Manet Pink”.

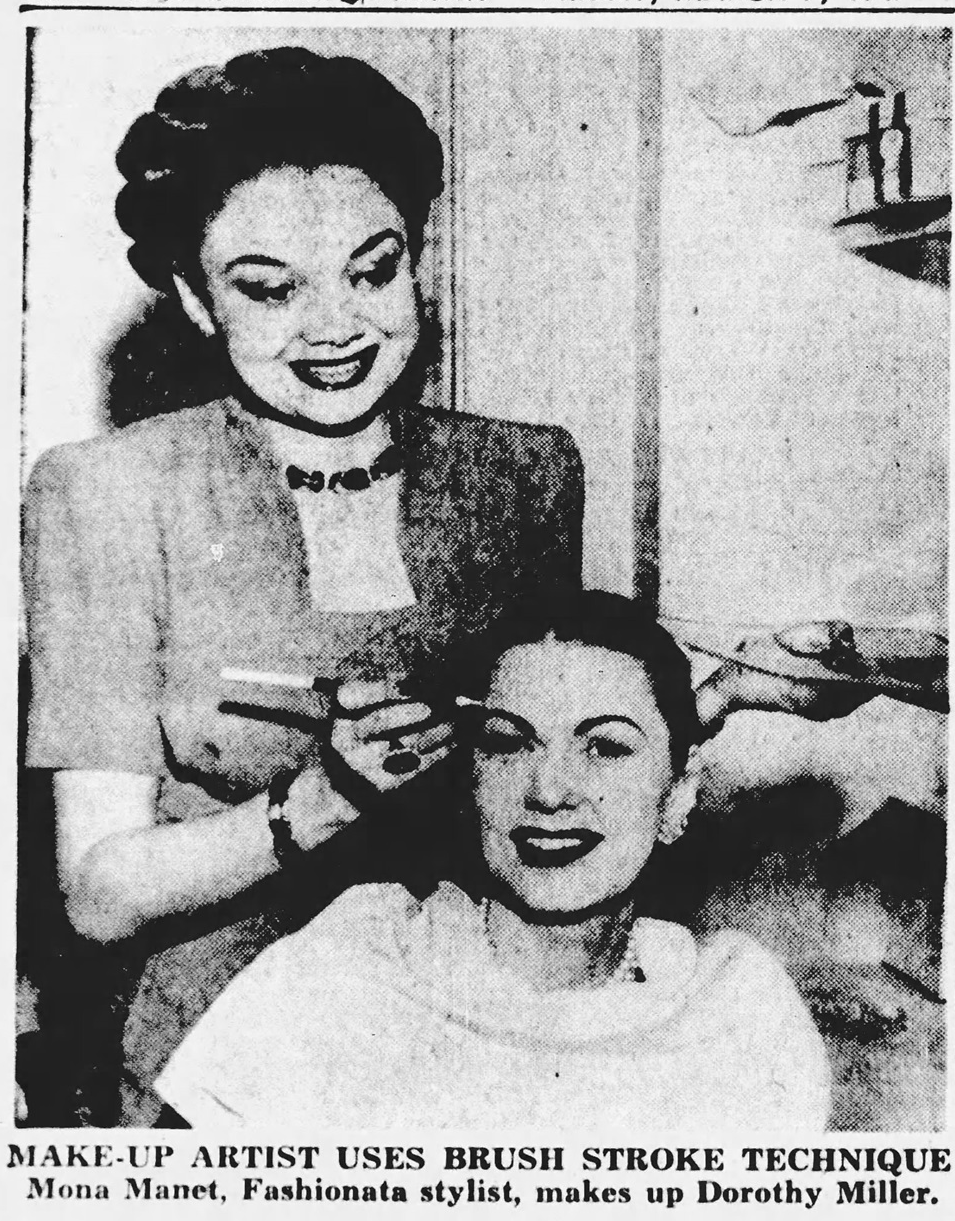

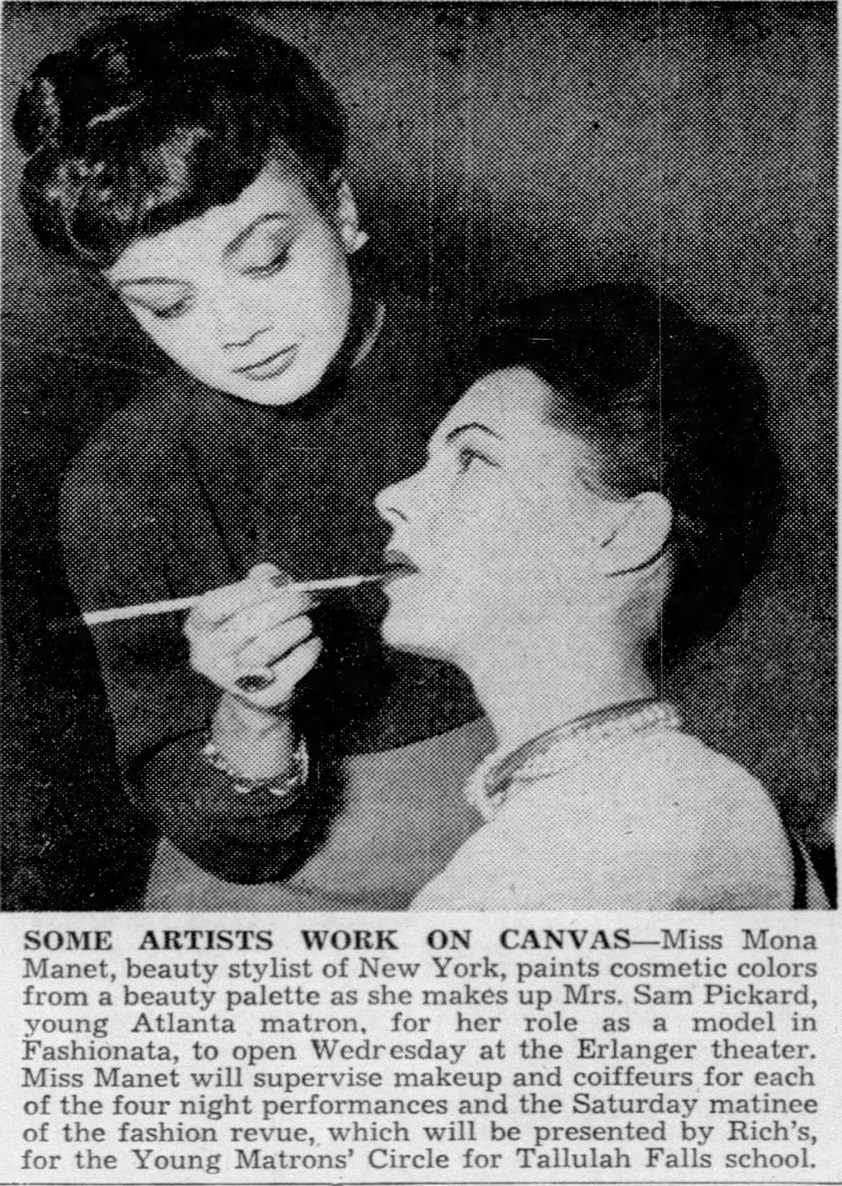

Roxborough’s advice and techniques were largely in keeping with the others of the time. She did have some unique tactics, however, including applying a very heavy face of makeup and removing most of it. According to Roxborough, this technique resembled the Chinese art of flower arranging in which a large bouquet is gathered and one flower at a time is removed until “the most piquant and satisfying effect has been accomplished.” Indeed, Roxborough seemed to have an affinity for Chinese culture, creating several hairstyles inspired by those worn by Chinese women and launching a beauty oil that she claimed was based on an ancient Chinese practice of using oil instead of a cream/lotion to moisturize both face and body. At times, she also used Chinese calligraphy brushes to apply lip and eye products. Chinese dignitaries, including a military captain, attended the opening of the new department in her salon, the Lotus Room, in September 1943. The event presented “an original kind of beauty demonstration stressing the Chinese influence in this year’s Fall styles…it is Miss Manet’s idea that Chinese make-up devices can be added to our American concept of beauty.”

She was also known for quick, streamlined beauty routines. In late 1942 the Associated Press reported on a beauty demonstration on 5 women by Roxborough and her salon workers. All of the women were serving in the military and had little time for treatments; however, as the mantra for American women during WWII was “beauty is your duty”, it was expected that all women, whether in the military or civilians, were to be perfectly coiffed and made up at all times. While the routines described in the article seem ridiculously long by today’s standards, in reality they were pretty quick: one factory worker had “a scalp treatment, shampoo and rinse, hair style, manicure, pedicure, clean-up facial and makeup which took only 64 ½ minutes.” The Lotus Room, in addition to being Chinese-inspired, offered much the same speedy, “assembly line” routine. Clients could get the “main essentials” of a shampoo, wave, manicure and makeup in 50 minutes. Interestingly, the concept of head-to-toe service would be greatly enhanced in several Black-owned salons, including the Rose Meta House of Beauty and Carmen Murphy’s House of Beauty, a few years later. This is entirely speculative, but I wonder if Rose Morgan and Roxborough were aware of each other as Roxborough occasionally socialized in Harlem, where the Rose Meta salon was located. And perhaps Carmen Murphy was aware of Roxborough’s salon as she set up shop in Roxborough’s hometown of Detroit, where she was still in touch with family there.

Finally, as Mona Manet, Roxborough was one of the earliest makeup artists who advocated for the use of a lip brush to apply lipstick. This practice would become hugely popular later in the 1940s and throughout the next decade (stay tuned for a post on Martha Lorraine lip brushes and other gadgets for a defined lip in the 1950s.)

In between operating the salon and providing makeup artistry for fashion shows and plays, Roxborough wrote ad copy and columns for a multitude of brands and publications beginning in 1945. In July of that year she was hired to be director of cosmetics for Lucien Lelong, but just two months later, she assumed the role of cosmetic editor at American Druggist, listed as “formerly” of Lucien Lelong. At American Druggist she wrote such pieces as “How to Be a Cosmetician” and “Classroom for Cosmeticians: Summer Cosmetics.” In February 1946 she began writing for Fascination magazine in addition to American Druggist, but left Fascination in March 1947, most likely because it folded. Less than a year after that, in February 1948 Women’s Wear Daily announced that Mona Manet had left American Druggist and was appointed as publicity director to Chen Yu, a company known primarily for nail polish (and rampant appropriation and stereotyping of Chinese culture, which may have aligned with Roxborough’s interest in Chinese fashion and beauty.) All of this job-switching suggests another mystery – was it simply the nature of the industry for workers to constantly be moving from one company to the next, or was Roxborough concerned about her true identity being found out and felt the need to move frequently to keep any suspicions at bay? But given how closely connected the industry was (and still is), this doesn’t seem plausible. If she was found out, word would spread quickly so there wasn’t much of a point in moving on to new positions.

All of Roxborough’s success as a beautician could not compensate for what was most likely a lonely existence. She had to be very careful about being seen in public with her Black friends in the city as well as her family when they came to visit, and mitigating public appearances meant seeing the people she was closest to infrequently. She lived with a white roommate, and all of her colleagues in the beauty world knew her as white. Her career would effectively be over and even her personal safety could be at risk if it was discovered she was Black. At the same time, while Roxborough was not estranged from her family, they were reportedly less than pleased with her decision to live as a white woman. Once again, Roxborough was unable to be fully embraced by either whites or the Black community. It could have been the inability to ever feel truly accepted that led to Roxborough’s fatal overdose of sleeping pills on October 2, 1949. Whether her death was intentional or accidental we will never know, but her family believed it was an accident, their reasoning being that she did not leave a note. They held a small, private funeral for her, and while the Michigan Chronicle ran the headline “Elsie Roxborough Dies,” her death certificate listed her as white. No one in New York City was made aware that she was Black.

The larger topic of racial “passing” and its implications are far beyond the scope of this post, especially as I’d like to focus on Roxborough’s role in cosmetics history. I personally think Roxborough could have gone to New York as a Black woman and become a hugely successful beauty entrepreneur who was able to meet the needs of Black customers as Sara Spencer Washington, Madame C.J. Walker and Annie Turnbo Malone did before her. Or she could have continued passing as white and pursued a beauty career even further than she did. She was described by her colleagues as an “up-and-coming young beautician with an important future” and “one of the most gifted writers in the cosmetic realm.” Black or white, she was quite talented at makeup and hair in addition to writing. But it seems that she did not engage in the beauty realm out of genuine interest. Instead, perhaps Roxborough saw being a white beauty expert as a way to get closer to her true passion, which was playwriting. Providing the makeup and hair styles for performers/models at fashion shows and coordinating corporate beauty presentations was getting her foot in the door – maybe she thought that if she could prove herself more than capable of managing these types of productions, she could break into writing and directing high theater more easily. Having been mostly shut out of that world as a Black woman previously, living as white and overseeing various skits and performances (which she was doing as of 1947 – her credits for most shows had changed to “written and staged by Mona Manet”) allowed her a better shot at achieving her dream of being a serious playwright.

In any case, I hope this post makes clear that Roxborough contributed significantly to makeup history, no matter how she identified racially. It also serves as a reminder of the enormity of white privilege, and that while the beauty industry afforded more opportunities for both Black and white women, the playing field was and remains uneven along race and gender lines.

*The Mona Manet name for cosmetics was patented in March 1941 with a claims use date of December 28, 1940, so Roxborough was most likely using the name throughout 1940.

Sources

Advertisement, Harper’s Bazaar, vol. 75, iss. 2765, May 1942, 18.

Erin Allen and Ken Coleman, “Passing: The Story of Elsie Roxborough.” Stateside podcast, March 24, 2022. https://www.michiganpublic.org/podcast/stateside/2022-03-24/stateside-podcast-passing-the-story-of-elsie-roxborough

American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review, October 1943, 52.

American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review, December 1945, 54-55.

American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review, January 1948, 79.

Donna Davis, “Beauty for Sale: Everything New in Beauty,” Hit Parader, December 1942, 22.

Annette Donnelly, “Beauty in a Hurry: This Speedup Era Takes Its Turn at Charm, Too,” Daily News (New York), August 23, 1943.

Drug and Cosmetic Industry, volume 57, issue 1, July 1945, 81.

Ruth Finley, “Fashion Calendar”, September 3, 1943, 3.

Helen Flynn, “Christmas Counterpoints,” Town & Country, vol. 97, iss. 4243, December 1942, 44.

Kathleen A. Hauke, “The ‘Passing’ of Elsie Roxborough,” Michigan Quarterly Review, vol. 23, no. 2, 1984, 155-170.

Langston Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander: An Autobiographical Journey. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2015 edition (originally published in 1956).

Jacqueline Hunt, “Make-up Keyed to Hair-do for Most Flattering Effect,” Anadarko Daily News, April 8, 1941.

Martha Parker, “Bigger Imports of Needed Tropical Oils for Lip Rouge Made Possible by Navy,” New York Times, November 16, 1943.

Gayle Wald, Crossing the Line: Racial Passing in Twentieth-Century U.S. Literature and Culture. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000, 82-84.

“Miss Manet with Chen Yu,” Women’s Wear Daily, February 20, 1948, 30.

Makeup Museum (MM) Musings is a series that examines a broad range of museum topics as they relate to the preservation, research and exhibition of cosmetics, along with my vision for a physical Makeup Museum. These posts help me think through how I’d run things if the Museum had more resources or occupied a physical public space, as well as examine the ways it’s currently functioning.

In 2024, the Makeup Museum’s 15th year, I did a significant amount of reflecting. I especially wanted to dig deeper into how the Makeup Museum can participate in creating social change. This is an incredibly broad topic so it will be broken into several sections that relate to social justice. Picking up where volume 29 of MM Musings left off, volume 30 will explore the idea of what I’m calling problematic objects – those pieces with clearly racist, colonial or otherwise offensive characteristics. The exhibition of these objects is part of the larger topic of decolonization of museums, which will be discussed in detail in a later MM Musings post. For this installment, however, it seems prudent to focus on just one way in which the modern museum can work towards decolonization (spoiler: I don’t believe it’s possible for many museums, the Makeup Museum included, to ever be fully decolonized.)

As I mentioned in the follow-up post on cultural appropriation, nearly every single brand is problematic if you look closely enough. Even if they appear innocuous on the surface, all modern makeup is inherently the product of an ugly industry rooted in racism, labor exploitation, animal testing, and a tremendous disregard for the environment; it was not created with anything except profit in mind, harmful outcomes be damned. In her book The Ugly History of Beautiful Things, Katy Kelleher describes the history of dangerous beauty treatments (lead face paint, belladonna eye drops, toxic lash tints, etc.) and how the desire to obtain physical beauty through makeup remains unchanged today, with many women feeling like they have no choice but to purchase and use makeup. “Makeup is a way to dominate one’s own body, molding it into shape so that its form better coincides with the beauty standards of the time…makeup can have serious benefits and terrifying consequences; it can help you land a job and it can give you cancer…any risk, even the risk of physical harm, tends to feel ‘worth it’. Because physical beauty is valued so highly, people are often willing to set aside their own discomfort in order to achieve this state.” Kelleher also includes a rather poignant quote from American author Ursula K. LeGuin, who said, “I resent the beauty game when I see it controlled by people who grab fortunes from it and don’t care who they hurt. I hate it when I see it making people so self-dissatisfied that they starve and deform and poison themselves.”

Given the larger issue of how the industry was built, its continued perpetuation of beauty standards and significant contribution to climate change, can there really be any makeup objects that aren’t problematic? Can we separate makeup from the industry and beauty standards? In reading two recent books on a similar topic – separating art from the artist – I don’t think it’s possible to fully untangle makeup from the industry that produces it. And it’s not clear what separating the art from artist actually means; in reading both Erich Hatala Matthes’s Drawing the Line and Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, I believe separating means enjoying the work of the artist and largely ignoring all the horrible things they’ve done. I’ve concluded that generally speaking, it’s impossible at the organizational level to separate makeup from the industry and standards that produce it. So now what? How does a museum educator or curator decide what to collect and display, and how? Should museums even exist, especially one dedicated to something as fraught as makeup? Most experts agree that museums should continue existing, but must completely reframe their collections and institutional histories to reveal the truth behind them. They must be honest in how their collections came to be, and add context to some of the pieces. And for some museums, repatriation of objects belonging to cultures outside of their own is necessary.

Obviously I don’t think the Makeup Museum should cease existing or collecting, even though makeup will always be historically rooted in negative things. There is a positive side to it; makeup history and contemporary makeup culture intertwine with many other areas of history and research and can teach us so much. Plus, makeup provides a very accessible outlet for creative and artistic expression, and can also contribute towards gender affirmation. Along those lines, it doesn’t mean we can’t personally enjoy makeup or that enjoying it makes us bad people. When I’m applying makeup, I’m actually able to ignore the problematic aspects of it because the joy of color and texture overtakes my knowledge. In that sense I am able to separate art from artist, and I think most of us are able to do the same. (Also, think about those who make a living off of applying makeup professionally – I do not believe they are immoral for creating art.) Dederer’s main argument is that art is highly subjective and personal/emotional. Most would not consider makeup and its brands to be art, so it might be misguided to use Dederer’s outlook here. But the Makeup Museum’s entire premise is that makeup is art, and most people have a personal connection to makeup, so I think her argument is relevant here. However, while most of us are personally able to separate makeup from its roots, it’s disingenuous and insensitive for a museum to do so. There is a responsibility for a nonprofit organization dedicated to educating the public to acknowledge the negative aspects surrounding makeup. Thus, maintaining the Makeup Museum raises the question of what to collect and how to display it. I spend a considerable amount of time debating whether to acquire racist or otherwise problematic objects and if I do, I’m unsure as if or how to present them. Ditto for sharing histories or profiles of not-so-great brands or people.

Ultimately I think problematic topics and objects should be shared. I believe museums have an obligation to educate and tell a complete story, and part of that is confronting uncomfortable truths. History should not be sanitized. Says Leah Huff, a graduate of the University of Washington, “It is important for us to be critical museum visitors who question how artifacts and pieces are acquired and why certain stories are told or forgotten. Visiting museums and memory institutions requires us to be critical of the narratives that are presented…[Museums] should emphasize truth-telling as opposed to presenting a white-washed version of history. The process of truth-telling involves speaking the truths about colonialism. Museums should not present narratives that glorify the age of exploration. Rather, they should show the consequences of Western expansion, colonialism, and imperialism.”

Artist and activist Michelle Hartney, who added her own labels to the walls of the Metropolitan Museum of Art as part of her Correct Art History performance piece, agrees. “We need these works of art to remain in museums so we can learn from them,” she said. “Educating and presenting the truth is how we learn and do better; this information would be a powerful educational moment because it will show how long the patriarchy has ruled over women…In my opinion, the institution is not acting in accordance with their ‘profession’s highest ethical standards and practices’ when they knowingly eliminate negative narratives from an artist’s legacy, often using the excuse that it distracts from the art and can change a viewer’s experience with the art.”

Matthes also agrees that problematic art and artists should not be “canceled” by being removed from public view.* He also points out the danger of glorifying or honoring certain artists by allowing solo exhibitions that do not address their pasts.

Now that we’ve concluded the negative aspects or background of particular artwork or artists should be displayed, how should museums go about doing that?

Critic Candy Bedworth, writing for Daily Art Magazine, states: “Hold to account all the galleries, museums, curators, collectors, art historians, and inheritors of artists’ multi-million-dollar estates who prop up the systems of oppression and refuse to hear the voice of the victim. These people must set the work in context.” In other words, contextualize the object in a way that focuses as much as, if not more, on the oppressed rather than the oppressor. The Independent broke down one example in the British Museum (might not be the best museum to use as the British Museum is a leader in problematic practices, but this particular case is enlightening). The bust of noted enslaver Hans Sloane now has an updated label that discusses his role in the UK’s history of slavery and colonialism, and displays it alongside other objects that call attention to Black history rather than simply lingering on the colonialism and racism. In this way a useful dialogue can be created. “Sloane’s bust will be exhibited alongside objects, situating it against a backdrop of the British Empire and slavery. The Museum’s website already reflects this, providing information on its founder’s links with slavery. This kind of contextualisation will help us to understand the role the UK has played in both the slave economy and colonialism, where simply cancelling the object would not…[The] focus here isn’t on retaining Eurocentric history – it’s on retaining the Black history intertwined with it. If we throw such objects out with the trash, there’s a risk that we won’t remember the shameful parts of British history in years to come, or the lives of those slaves employed by Sloane and his wife…[We] should use the potential offensiveness of artefacts to create dialogue. If we retain such objects, but make it known that they emerged from this context of discrimination and injustice, we won’t inadvertently cause more damage in our attempts to mitigate history.”

Using a vintage tube of blackface as a Makeup Museum example, perhaps one way to reframe or recontextualize it would be to show it next to an object that, while equally problematic on the surface, could actually serve to demonstrate how the Black community is highlighting the inequities in the makeup industry. In the spring of 2024, Youthforia launched new shades of its best-selling foundation after customers requested a wider range for dark skin. However, the deepest shade was nothing more than jet black paint. My mind immediately jumped to blackface and how a company in this day and age could be so clueless about the past. Fortunately, consumers were quick to call out the company, with beauty influencer Golloria leading the way. Swatching the foundation on one side of her face and the other with regular black paint, she gave a first-hand demonstration of what an incredible miss this was. While blackface was theatrical makeup historically used by white performers and has little to do with commercial makeup intended for deep skin tones, there is definitely a parallel here. Maybe showing these objects alongside each other could educate about both the history of blackface and efforts to ensure that companies today don’t reference it.

It seems like a relatively simple solution: make certain that object and exhibition labels provide adequate information on their problematic aspects, and present the objects in a way that does not glorify or condone them and instead open a dialogue. But a bigger question remains: where to draw the line? I won’t purchase anything from Jeffree Star’s brand, but I’m still buying Chanel, a company whose founder was a Nazi sympathizer (and the fact that the company still has not acknowledged that is troubling). Why do I think it’s permissible to blog about something like Tattoo, but I don’t feel right discussing Max Factor’s Pan-Stik in the shade “Chinese” that I bought last year? What are the boundaries of acquisition and display? Writes Dederer: “I wished someone would invent an online calculator — the user would enter the name of an artist, whereupon the calculator would assess the heinousness of the crime versus the greatness of the art and spit out a verdict,” Dederer writes. Similarly, I wish a calculator existed for the Makeup Museum. How “bad” is an object or person, and does their cultural or historical importance outweigh their awfulness? Unfortunately, Dederer states that “a calculator is laughable, unthinkable.”

Thus, there is no neat and tidy answer. Matthes and Dederer both conclude that it’s up to the individual in terms of what art and media to consume. Everyone has their own limits and reasons, and I can’t explain what mine are for the Makeup Museum. Perhaps it’s how overt the offensiveness is, but even that can be subjective. Perhaps it’s how much backlash from the public the museum would receive for purchasing particular brands or bringing up certain histories, even if I provided a thorough explanation as to why the object was acquired or the history was told in a sensitive, nuanced way. I strongly dislike confrontation and am very thin-skinned, so I would be very upset to receive nasty comments or lose support over something I bought or a topic was not explained as well as it could be. Most of all though, it’s the fact that I don’t want to inflict emotional distraught among BIPOC museum visitors or visitors from other marginalized groups. I imagine that a general discussion of cultural appropriation causes less pain than the aforementioned tube of blackface, but again, this is my own perspective – I can’t speak for the Black community. I must remember that while it’s not my goal to upset anyone, it’s about impact, not intention. So even if I did not mean to offend, it might still happen.

We’ve established that in order to provide a comprehensive account of makeup history, the bad needs to be presented along with the good. And we can do that through adding context and information. But how can a museum accomplish that without inflicting pain?

There are some museums where horrific histories and objects are not unexpected, such as the Holocaust Museum in DC or the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project. These are quite obviously upsetting, but people can decide in advance whether they want to visit – given the museums’ names, visitors have some idea of what’s on display and can make a relatively informed decision whether to go based on their personal histories and emotional threshold. But in the case of the Makeup Museum, people may be caught off guard and possibly upset. I’m assuming visitors would not be thrilled to view, say, a whimsical lipstick case shaped like the Leaning Tower of Pisa next to a 1960s Halloween makeup kit featuring a range of racist stereotypes. It would incur a bit of whiplash, I would think. One way to handle this is to offer content warnings. I’ve put up a blanket statement on the Museum’s main collection page and will add warnings for exhibitions and blog posts that warrant them moving forward. And I would have to speak with the Museum’s web designer, but I bet there’s a way to blur certain photos and people can choose whether to view them. In terms of a physical space, the object would be on display but not quite so prominently (so as not seem as though the museum is honoring it), and there could be a warning posted before one enters the gallery.

But I don’t know whether all of these efforts are enough, or even which objects or topics deserve these protocols. Because of my own bias, something I perceive as fairly innocuous and not requiring a content warning might be devastating to another viewer. The issues of individual relationships to art, personal histories and subjective reactions are again raised. Also, there is a pitfall of showing problematic objects by themselves: even if a curator adds historical information and tries to recontextualize them by displaying alongside other objects, they inadvertently may be portraying the entire history of a certain group as nothing more than trauma. In her book The Whole Picture, art historian Alice Procter brings up the example of a sculpture carved by a member of the Haida people in the British Museum (I know, I know, not again – but it’s a good example). It is the only work by a Haida artist in the museum’s collection, and depicts a violent physical assault on a Haida woman. Not much else is known about the sculpture. Having this on display by itself and with no other context, Procter says, may actually reduce the tribe’s history to the violence they experienced. “[If] there is no commentary around how unique this object is, or context for the attack as part of the colonial history of Canada, the focus is exclusively on the act of the attack. The danger is that Haida culture ends up being presented as characterized by sexual violence.” People are more than their experiences of genocide and other horrors. So going back to our example of vintage blackface and Youthforia’s disastrous foundation, even though additional context would be provided for both and a dialogue opened between both the objects themselves and the audience, is that the best way to present these objects? Would it be less harmful to show these alongside something more positive, such as objects by Fenty?

The bottom line is that object interpretation and display will always pose a conundrum for the Makeup Museum. Many beauty standards are entrenched in white supremacy, and makeup, in part, still serves to meet those standards. As noted earlier, the modern industry was founded on many systemic injustices and continues contributing significantly to climate change and other harmful things. Even makeup that was not created by the industry, i.e. cosmetic objects made by Indigenous peoples, present a problem in that there is debate over whether these belong in white-founded and operated organizations. There are also varying degrees of “badness” and those are fairly subjective. What is off-limits to me to acquire or discuss may not be to another and vice versa. But none of this means the Makeup Museum shouldn’t exist, that it should stop collecting, or that what has been and currently being collected isn’t important. What it does mean is that it’s important to educate people about makeup’s toxic past and present without causing trauma, or at least, as little as possible, and center the perspective of marginalized groups as much as possible. It also means getting feedback on the Museum’s collection and display practices, developing a collections plan and code of values, and revisiting this post on ethics.

Have you ever been offended by or upset at something you viewed in a museum? How do you think the Makeup Museum can present objects that are particularly problematic?

*The removal of problematic statues and monuments in public spaces seems to be an exception to this approach. I think a rather genius solution lies in the Museum of Toxic Statues in Berlin.

Sources

“How can Museum Labels be Antiracist?” Exhibition at Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, September 9, 2020-September 10, 2021.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, “What Are a Museum’s Obligations When It Shows a ‘Problematic’ Artist?” New York Times, May 10, 2024.

Lydia Bunt, “Museums Are Right to Keep Artefacts on Display That Point to Britain’s Shameful Past,” The Independent, October 4, 2020.

Sophie Cox, “What Should We Do With the Work of ‘Immoral’ Artists?” Duke Research Blog, Duke University, February 14, 2023.

Claire Dederer, Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma. New York: Knopf, 2023.

Leah Huff, “Museum Decolonization: Moving Away from Narratives Told by the Oppressors,” Currents: A Student Blog. School of Marine and Environmental Affairs (SMEA), University of Washington, May 31, 2022.

Katy Kelleher, The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and Consumption. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2023.

Erich Hatala Matthes, Drawing the Line: What to Do with the Work of Immortal Artists from Museums to the Movies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Alice Procter, The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums and Why We Need to Talk About It. London: Cassell, 2020.

Nadja Sayej, “’The Art World Tolerates Abuse’ – the Fight to Change Museum Wall Labels,” The Guardian, November 28, 2018.

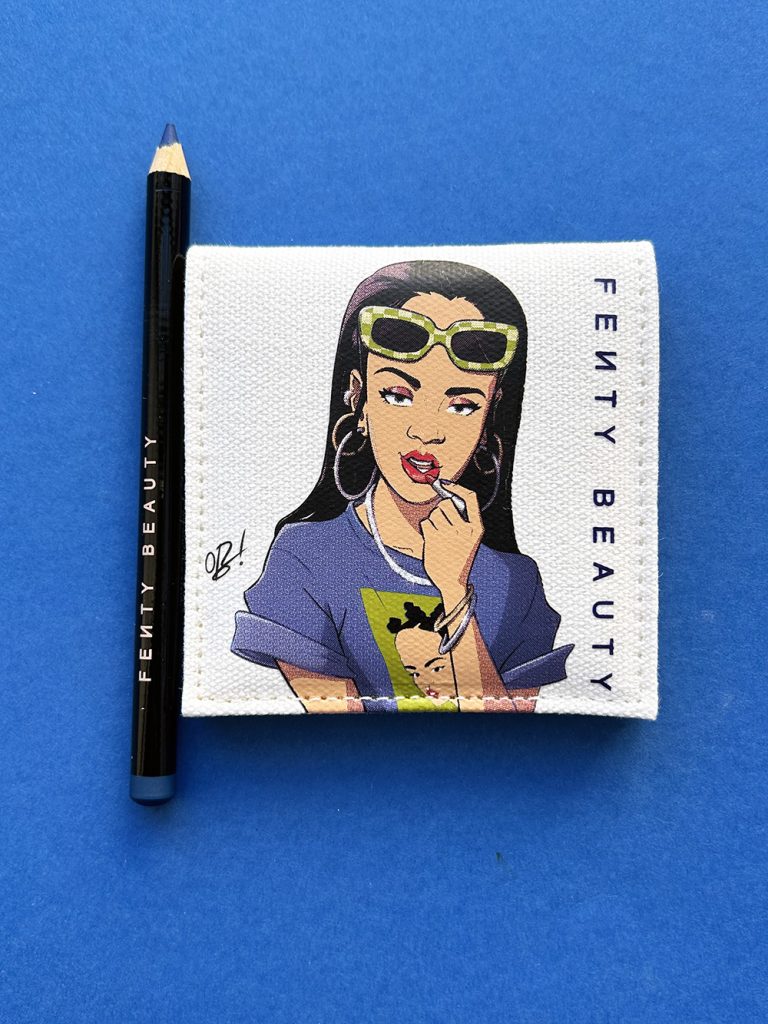

Fenty Beauty, the brand founded by musician Rihanna in 2017, had possibly its most adventurous releases in 2022. In August that year the company launched a set of 6 packets containing a mystery substance produced by cheeky Brooklyn art collective MSCHF (which I hope to cover eventually), and in December, a $500 crystal-studded lipstick case to celebrate the brand’s 5th anniversary. While I’ve been using Fenty since its inception – the matte foundation, cheek stix, and lipsticks are excellent – it’s the limited-edition products with special packaging that go into the Makeup Museum. However, having skipped this year’s holiday lineup, a collab with video game-inspired animated series Arcane, today I’m looking back at 2022’s Navy collection. Illustrated by L.A.-based cartoonist Obi, the Navy set is a nod to the nickname for Rihanna’s fan base, which in turn comes from one of her song lyrics, 2009’s “G4L”: “We’re an army / Better yet, a navy / Better yet, crazy”

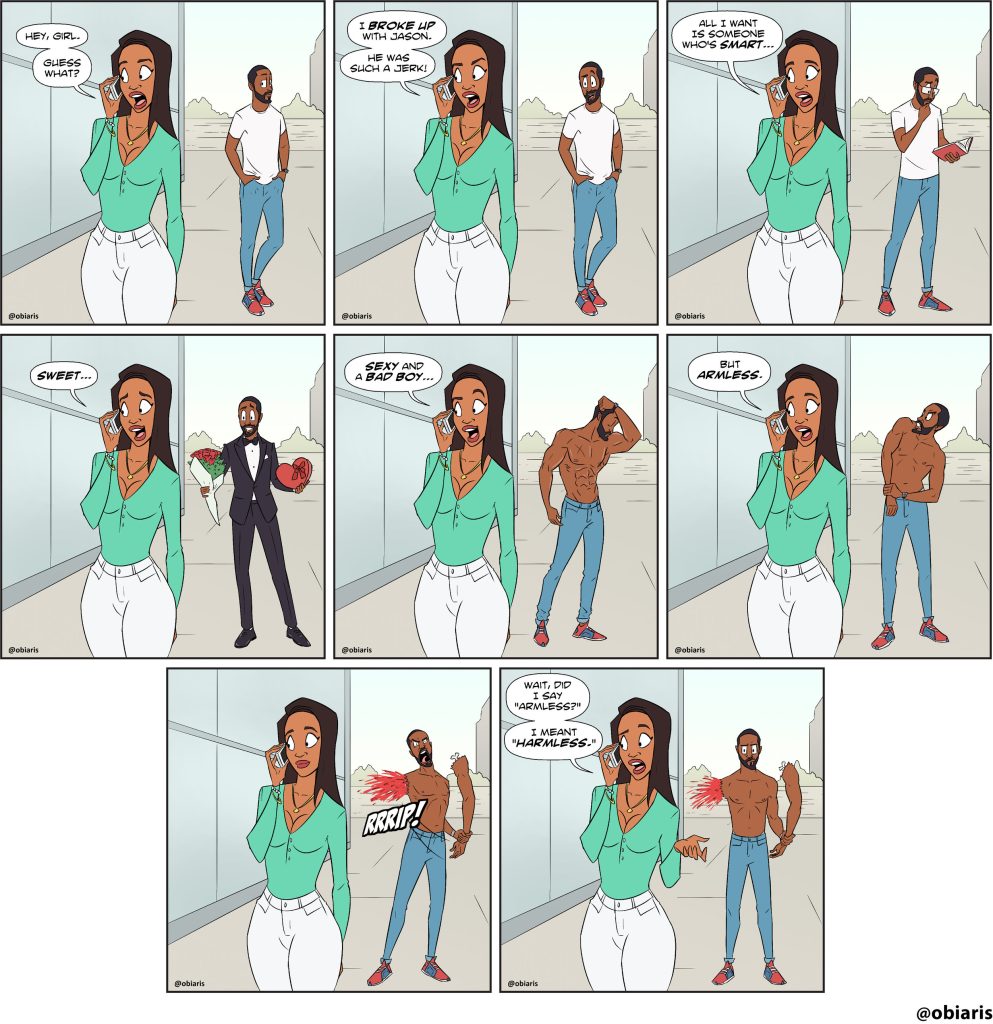

Before we delve into the set, let’s take a peek at the work of the artist behind it. First generation Nigerian-American Obi Arisukwu was born and raised in Houston, Texas. Strongly influenced by cartoons and superheroes, particularly the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, he began drawing at the age of 3. He earned a Bachelor’s degree in Visual Design and went on to become the lead graphic designer for ConocoPhillips, doing illustration on the side. After 4 years in the corporate world, however, he had enough. “When I was working at ConocoPhillips, I loved it at first. Then slowly and slowly, it became the same mundane pattern of going to work, being in a cubicle, and never being able to express my creativity. My talents weren’t being utilized the way they should have been. For instance, I was the head graphic designer there, but I was doing PowerPoint presentations. After a while it was kind of, “What am I here for? This is not really what I want to do. I really want to get into cartoons.’”

This was also a period of rapid growth for Instagram, where Obi would be inspired by other artists’ work as well as their ability to quickly cultivate large audiences. At the age of 30, he quit his job and moved back in with his parents to pursue illustration full-time. Obi acknowledges the first 6 months were difficult, as he had to learn to set up a business and earn clients, but ultimately his talent and perseverance paid off. “Living with my parents, they’re really great. They’ve always supported me and it’s like a really good Airbnb. It’s definitely tough because when you first quit and go on your own, you’re going to go through that period, that downfall, of where you’re not getting any business or no clientele because you’re still working on your service, still working on getting yourself out there. Then, for me, after like six months, I started getting a lot more projects. I really stopped doing graphic design work to focus more on illustrations. This is one of those things where you don’t give up.” Yay for supportive parents! (Side note: His mother’s only request was for Obi to buy her a Chanel bag after he had achieved success.)

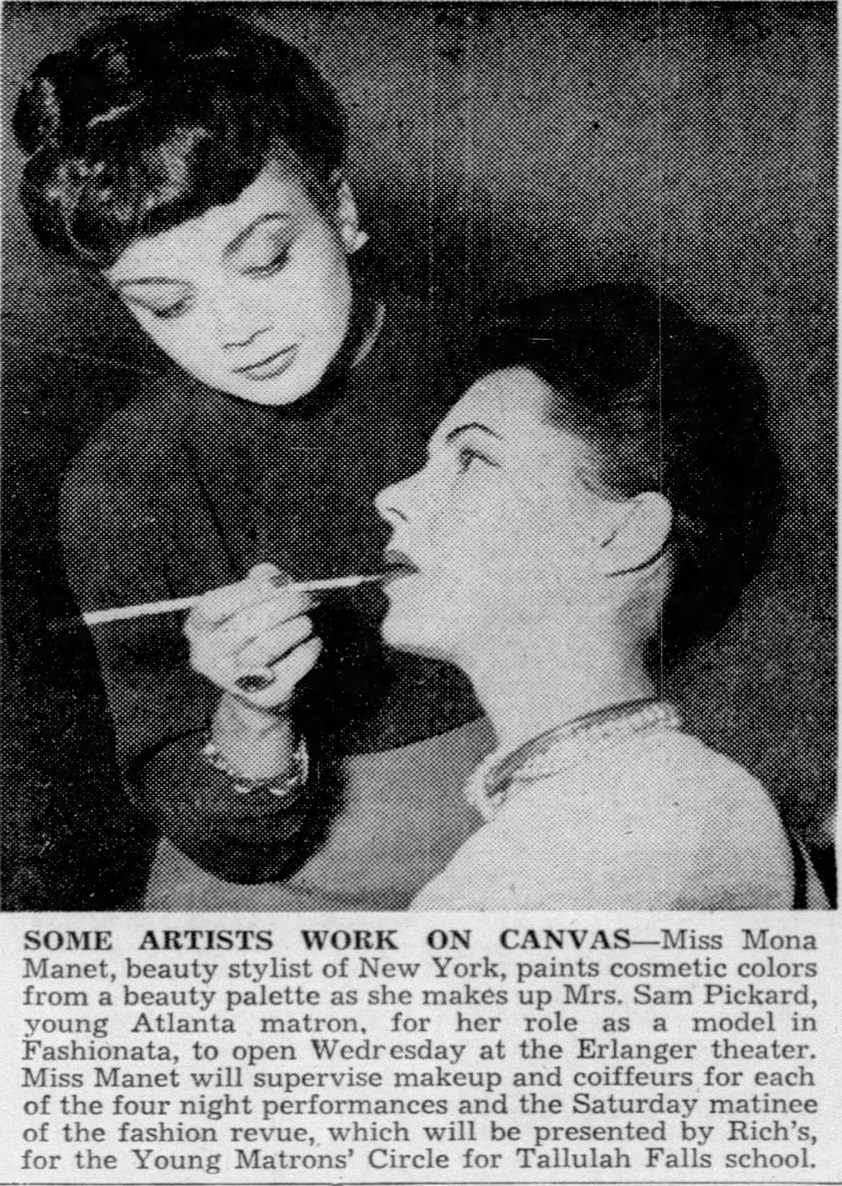

In December 2017 Obi posted a comic strip loosely based on his life as a millennial. This proved enormously popular – it was the most engagement he had ever received on his Instagram posts – and he began posting a new comic each Friday. “The comic strip parodies real life situations like dating, friendships, politics, etc. Even though I’m the main character in the strips, I’ve taken on the role as the ‘every man’ so that the comic strips is relatable to everyone who reads it. [The strips were just the everyday things that we go through [as] millennials…Whatever it is and kind of making it to where people can just resonate,” he explains.

It’s a gentle humor that doesn’t stray into corny “dad joke” territory. I’m not too up to date on my comics and cartoons, but Obi’s work seems to be a breath of fresh air in an age of sarcastic, “edgy” or even offensive animated series (South Park, Family Guy) or the nonsensical (Aqua Teen Hunger Force and other Adult Swim programming). While I’m partial to the likes of Archer and Metalocalypse, I also appreciate Bob’s Burgers and Home Movies, or comics such as the Far Side. A light-hearted, softer type of humor is not a bad thing!

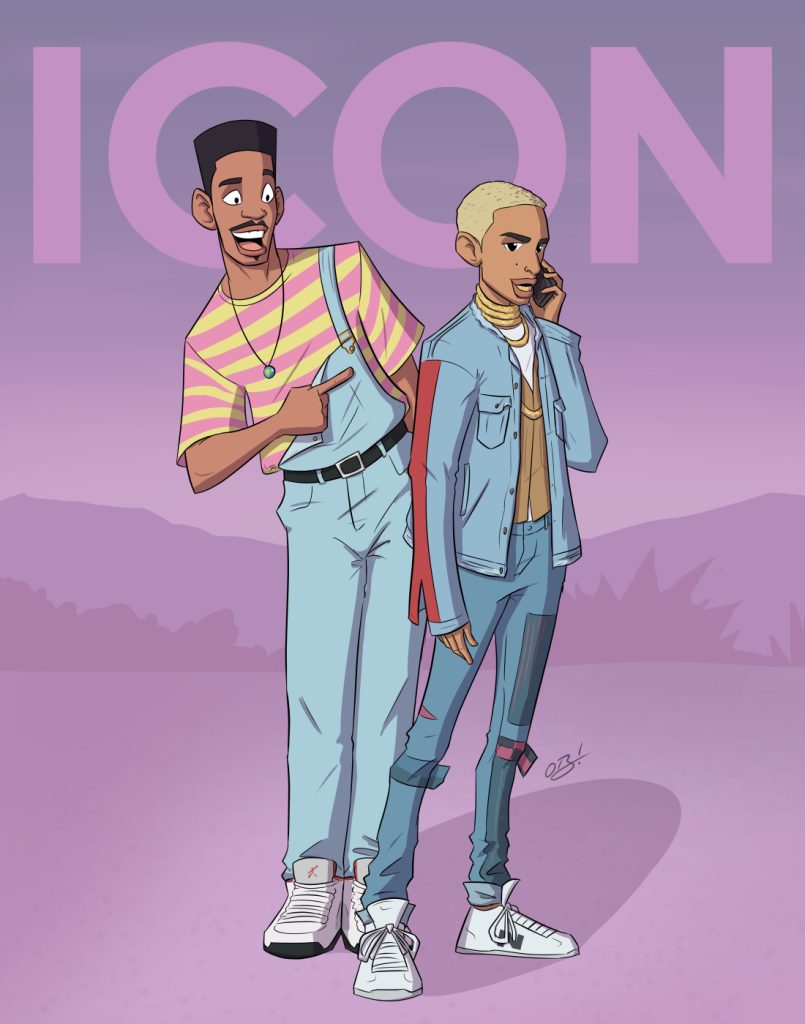

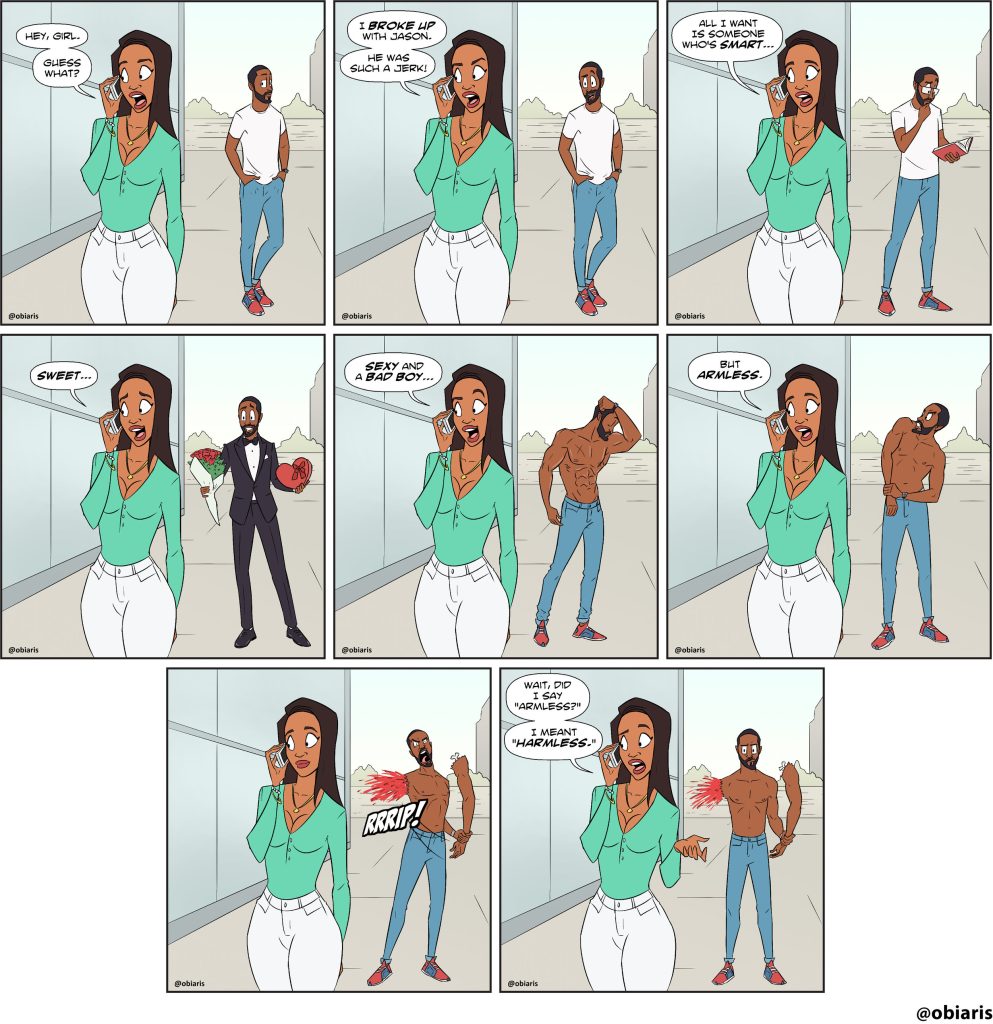

Obi continued with the comic but also drew Black pop cultural icons, athletes and other important figures. “There’s a lot of awesome things happening in the Black community, so I like to showcase that in my art,” he says. In 2018 Obi’s illustration of Childish Gambino from his “This Is America” video went viral, earning over 30,000 likes in 24 hours. Obi followed that up with another viral post featuring Will & Jaden Smith.

While these viral pieces may have led to the collaboration with Fenty and other opportunities, it was Obi’s “every man” comic that landed him his own animated series on HBO. The news was announced in early 2021, but it’s unclear as to when the show will actually debut. It will have the same vibe as his comic – a show about day-to-day life as a Black millennial man. Obi expands on his vision for the show as it pertains to race: “This cartoon is not just about me, it’s about society as a whole. It’s just kind of through the lens of a Black person. But it’s definitely a cartoon that everybody can watch…My biggest thing that I want to do when it comes to bringing diversity, especially with my Obi cartoon, is that I want to show the world that we live in as Black people, that’s not all about us getting shot by the police…we’re more than just victims all the time. I want to have four Black main characters who literally are just living life trying to make it in this world…OBI is the daily experiences we all can relate to, it’s just from the Black perspective. We always see us getting shot. We see slavery and racial injustice all the time. Sometimes we [Black people] need to escape from that. We’re more than the racial shit that happens to us. We have other things going on too. This cartoon will have moments where it does address being Black, but it’ll still have the comedy element to it. We’re more than our racial injustices…This show is about all the day-to-day, societal issues that go through as Black people that other races can relate to as well and laugh at with us.” This is a really important point that I think sometimes gets lost, especially in conversations regarding racial justice. Black people are more than their trauma and while it’s critical to acknowledge racism and work towards dismantling it, highlighting everyday life is also essential. Indeed, Obi rarely explores instances of racism, but when he does, it’s still done with the same humor.

(images from obiaris.com)

(images from obiaris.com)

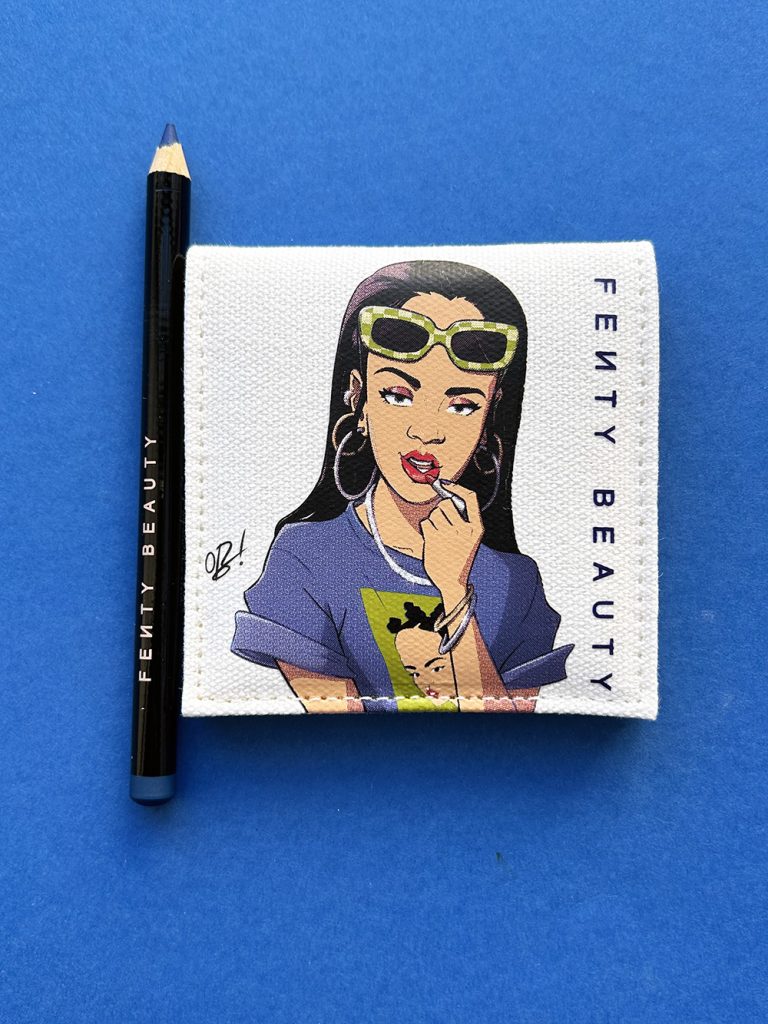

Now, time for the makeup! The Navy set consists of a zipped canvas bag, a refillable lipstick in a limited edition blue case, a navy blue eyeliner and a cute little mirror. The lipstick shade is MVP, a classic red. (As I didn’t want to break the seal on the refill I don’t have pictures of it, but hopefully the stock photo will show you how pretty it is.)

I spent a good hour searching for photos of Rihanna as she is shown on the set – one with her hair down, green patterned sunglasses perched on her forehead, and lots of jewelry – and the other depicting her with Bantu knots, a green fur coat, white tee and blue cargo pants. Then I watched Obi’s Instagram video about the set and realized that, being an artist, he used his imagination to create these images rather than blindly copying her actual outfits. As someone who does not have any sort of creative flair, it didn’t occur to me that this would be his process! Anyway, there are a few images of Rihanna that can be seen in the video.

The collection was generally well-received, and the retail price of $58 for the set was quite reasonable given that it was adorned with original artwork and the practicality of the items included. Everyone can use a makeup bag, mirror, navy eyeliner and red lipstick, no?

However, some Instagrammers took issue with the depiction of Rihanna’s forehead. Between Fenty Beauty’s account and Obi’s, there were roughly 100 comments accusing Obi of making her forehead too large.

Normally I don’t address meritless criticism such as this – I try to “ignore the haters” as they say – but the reason I’m bringing this up is because I am massively confused. I think her forehead appears totally normal-sized. And while marketing teams sometimes slip up and let mistakes happen, even major ones, I would think that if it really was out of proportion the set wouldn’t have been allowed to be sold and Obi would have had to go back to the drawing board, literally. Beauty brands, particularly celebrity lines, fiercely protect the images of their founders and must show their them in the best possible light at all times.

This is just one of many things I’d like to chat with the artist about! I would have emailed Obi for an interview as he seems incredibly down to earth and approachable, but the week between Christmas and New Year’s isn’t really the best time to reach out to people, so in the end I decided not to. I am still wondering how the collab came about, what the process was like working with the company, if he got to meet or interact with Rihanna at all, and why he chose the images he did as inspiration when creating the artwork for the set. I’d also like to hear what’s happening with his HBO show as I am eager to watch it, and, of course, if he ever purchased a Chanel bag for his mom.

What do you think of Obi’s work and the Navy collection? I really enjoyed it and hope to see more collabs with Black artists. As I’ve pointed out, the cosmetics industry is seriously lagging behind in this regard. I do have one regret, which is not entering Obi’s giveaway contest – he provided signed sets to 5 lucky winners. Obviously I’d love to have a set personally signed by the artist. 😊

Sources

Emerald Pellot, “Cartoonist Obi Arisukwu Is Bringing His Dream Animated Series to Life,” In the Know, March 16, 2021.

Niko Rose, “Obi Arisukwu on His Creative Journey, Project with HBO Max,” Blavity, September 30, 2021.

Sofiya Ballin, “Meet the Nigerian American Cartoonist Animating the Biggest moments in Black Popular Culture,” Okay Africa, November 8, 2018.

“Check Out Obi Arisukwu’s Artwork,” Voyage Houston, July 11, 2018.

Obi Aris Interview, Mint Mag, February 14, 2020.

Joann Njeri, Interview with Obi Arisukwu x Naija Comm, March 19, 2023.

These last two links seemed to have disappeared from the internet, alas.

https://www.sheenmagazine.com/cartoonist-obi-arisukwu-talks-starting-over-success-and-finding-the-funny-in-between/ – Oct. 16, 2018

https://knoonline.com/the-cartoon-life/ – Sept. 16, 2018

Hello! It’s been a while since anything has been posted at the blog. I just wanted to pop in and give a quick recap of my 72-hour voyage to the UK, where I presented “Makeup Design, Compulsory Beauty, and the Modern American Woman, 1920-1960” at the 32nd annual Women’s History Network conference at Royal Holloway University.

I had expected a virtual option, but upon learning there wasn’t one I had to make the very difficult decision to travel internationally for the first time in nearly a decade and traveling anywhere since February 2020. Between COVID anxiety, travel anxiety and my usual baseline state of “total basket case”, it was incredibly stressful and scary, but I didn’t want to miss the opportunity! Gotta build up that CV if I ever am really going to apply for PhD programs. 😉

Here’s the abstract: “From ‘automatic’ lipsticks and disposable face powder sheets to multi-use compacts and retractable brushes, the cosmetics industry introduced thousands of products during the first half of the 20th century to accommodate women’s rapidly changing lives. This paper will explore how certain makeup packaging reflected the fundamental shift in women’s daily activities, their relationship to beauty and their identity as modern women. I will highlight several key cosmetic artifacts that were specifically designed and marketed as more convenient alternatives to existing products. By allowing women to apply makeup faster or on-the-go, these objects were touted as cutting-edge, superior inventions that boasted freedom from time-consuming beauty routines and the hassle of cluttered vanities or purses, as well as the prevention of social faux pas. I will also examine how these artifacts embodied social expectations for women in terms of beauty and femininity. Novel makeup may have reduced the amount of time and labor women allocated to engaging in beauty practices; in doing so, however, these products tacitly encouraged women to adhere to beauty standards at all times. The modern woman could travel, work, participate in athletics, etc. but still was expected to maintain her appearance – thanks to new developments in makeup design.”

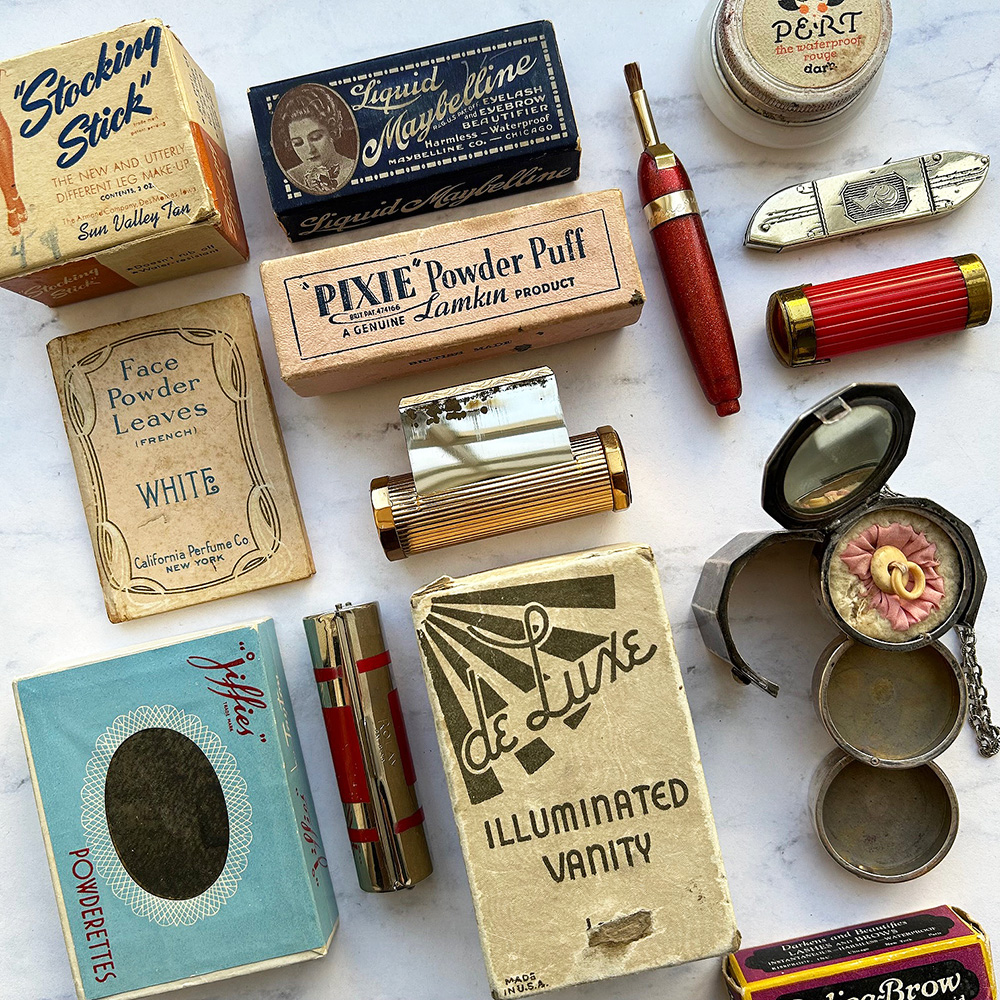

And here are some Makeup Museum objects that were featured in the presentation, along with some that fit the theme but not the 15-minute time limit – just couldn’t include everything.

Of course, some museum staff tagged along. We had a lovely tea at the hotel.

In addition to all my other neuroses, I have crippling social anxiety so I didn’t “network” as much as I could have, but I tried. Makeup Museum business cards made it into the hands of a few people. All in all, I think it went well and was worth the trip. I must give a shout-out to the wonderful Lucy Jane Santos, who posted the call for papers and kindly read through both the abstract and presentation – I would not have attended without her expertise and guidance! Oh, and if you’re interested in the topic, stay tuned for a post at the CHMSN Substack.

It's officially spring in the Northern hemisphere, but I still wanted to do a quick catch up on winter, which, for the purposes of this post was January-March.

It's officially spring in the Northern hemisphere, but I still wanted to do a quick catch up on winter, which, for the purposes of this post was January-March.

– So sad to have missed The Cult of Beauty exhibition at the Wellcome Collection, which closes on April 28. It features some truly amazing voices from the beauty arena, including Jill Burke (author of How To Be a Renaissance Woman) and Eszter Magyar (a.k.a. MakeupBrutalism.)

– Also bummed to have missed this exhibition on acrylic nails. Fortunately there's a book available!

– Dame Pat McGrath managed to break the internet with her porcelain doll-like makeup for Maison Margiela's spring 2024 haute couture show.

– There has been much discourse surrounding Sephora being overrun by tweens and their seemingly unquenchable thirst for…skincare?

– Out: "clean girl" makeup. In: the mob wife aesthetic.

– Could this be the oldest lipstick ever found? The jury is still out, but if it is in fact lipstick I'm enamored of the container.

– Don't forget to sign up for early access at the Black Beauty Archive!

– "Can skincare ever exist separately from harmful beauty ideals?" Enjoyed this piece over at Dazed, as I've been asking the same question for years but about makeup.

The random:

In '90s nostalgia, The Matrix and Office Space turned 25, while albums The Downward Spiral and Dookie turned 30.

So many amazing exhibitions in addition to the Cult of Beauty that I probably won't get to see: unicorns at the Perth Museum in Scotland, cute overload at Somerset House, bows at the museum at FIT, Barbie at the Design Museum, and Biba at the Fashion and Textile Museum – was dying reading this interview with brand founder Barbara Hulanicki about the makeup!

How are you? Are you glad winter's done?

2023 was a particularly quiet year on the blog and social media front due to some big projects! A book chapter, two grant proposals, two talks, and the website redesign meant I couldn't put out much content. I hope to remedy this in 2024, but I can't make any promises, especially as I'm writing another book chapter due in September, two more grant proposals, two papers and the website redesign is ongoing. Here's my attempt to prioritize projects this year. (Yes, I realize we're already 4 months in!)

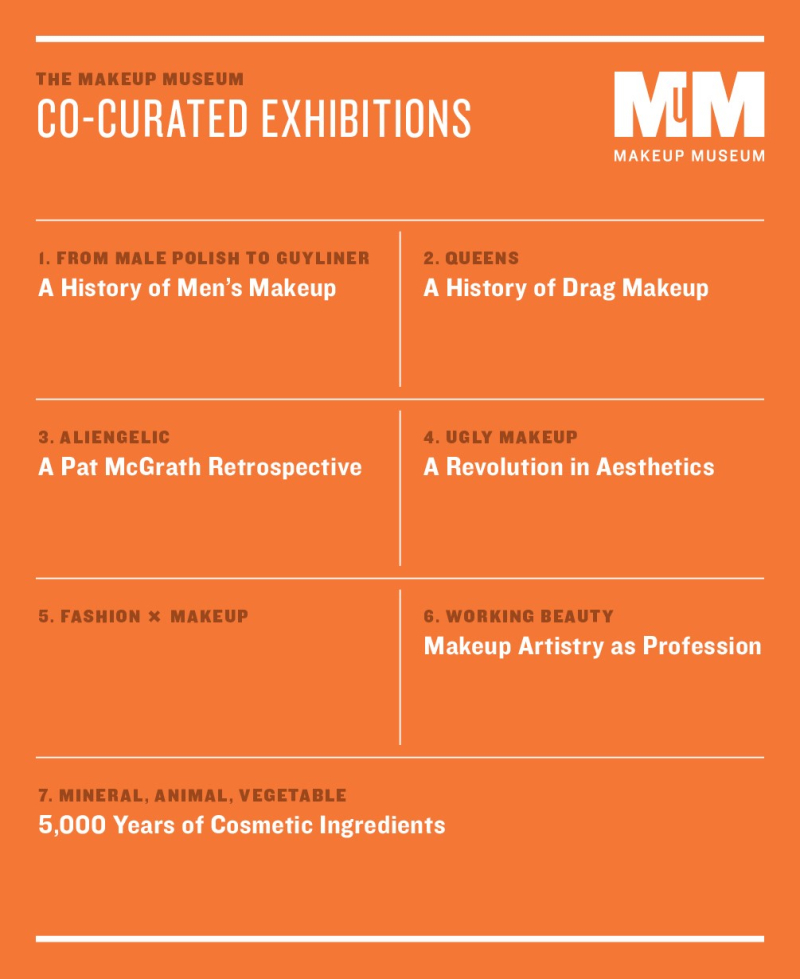

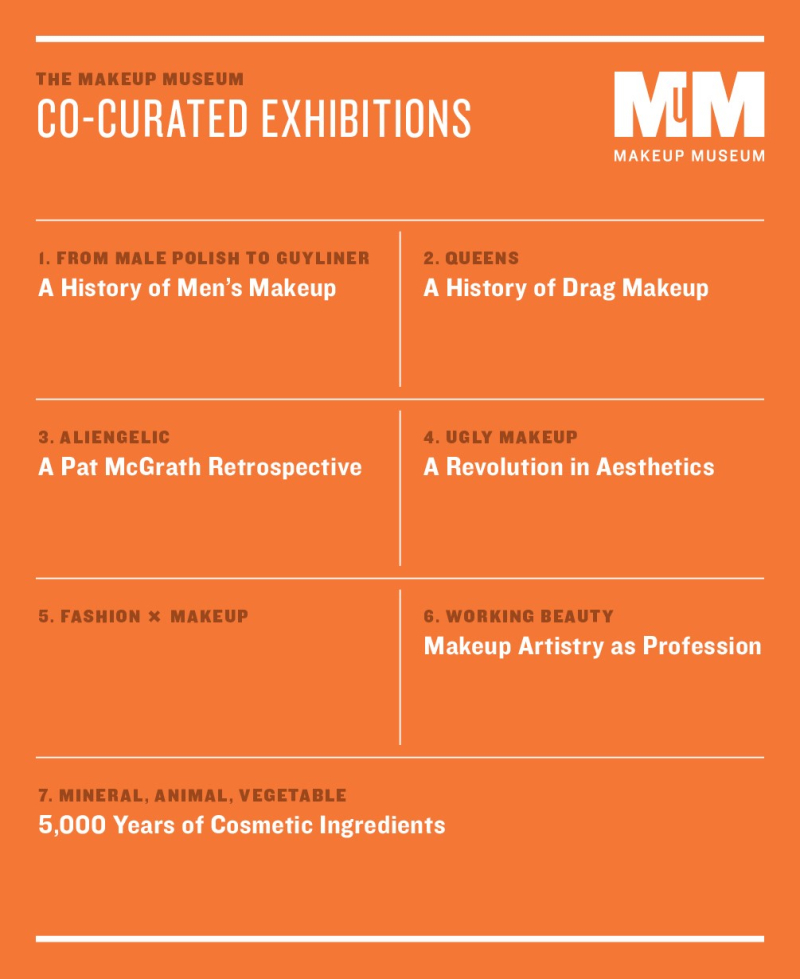

First up is the Museum's exhibition shortlist, the topics that I think are the most important and might be doable by myself. Following the same grouping as 2023, in addition to the shortlist, the second group consists of exhibitions that I think would have wide appeal but require co-curation, and the 3rd category is for lower priority topics, i.e. ones that are good but not quite as pressing as the shortlist. If the title has no notes next to it, that means the description and my thoughts on these haven't changed since previous years.

Priority:

- "Indies and Influencers: The Changing Makeup Landscape"

- "Youthquake: Teens and Makeup" – tweaked the title a bit from last year, and given all the hubbub around Sephora tweens as of late, the exhibition would include this age group as well.

- "Color History Through Cosmetics: Blue"

- "The Medium is the Message: Makeup as Art"

- "Flutter: A History of Eyelash Adornment" – So, this isn't a brand new topic as I mentioned it last year, but I did change around the working title and gave it a lot more consideration, and concluded that this most likely will be the next exhibition. There are so many different subtopics and areas to weave in, like when it was decided that long, dark lashes are beautiful, the dangers of lash tinting and false lashes, and moral considerations – lots of vintage lashes used human hair, which probably was not gathered in an ethical way. See also: mink eyelashes.

- "Ancient Allure: Egyptomania in Makeup"

- "Just Desserts: Sweet Tooth Revisited"

- "Beauty Marked in Your Eyes: A History of '90s Makeup" - It will be 10 years in the fall since I had this idea and not much progress, but I'm still not giving up!

- "Design is a Good Idea: Innovations in Cosmetics Design and Packaging"

- "Nothing to Hide: Makeup as Mask"

Here are the ones the Museum will need much help with.

- "From Male Polish to Guyliner: A History of Men's Makeup"

- "Queens: A History of Drag Makeup"

- "Aliengelic: A Pat McGrath Retrospective"

- "Ugly Makeup: A Revolution in Aesthetics"

- Fashion x Makeup (still haven't thought of a decent title!)

- "Working Beauty: Makeup Artistry as Profession"

- "Mineral, Animal, Vegetable: 5,000 Years of Cosmetic Ingredients"

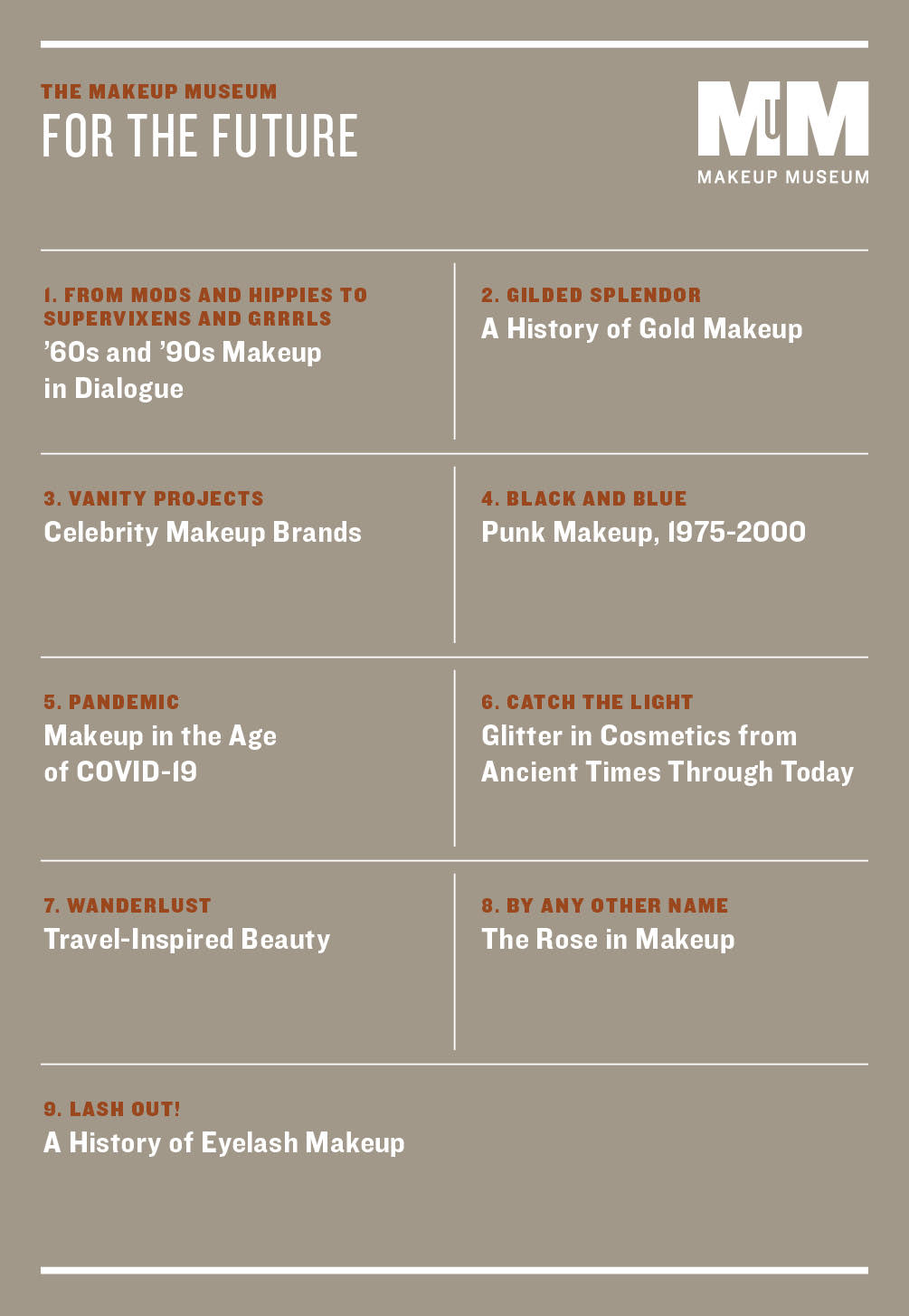

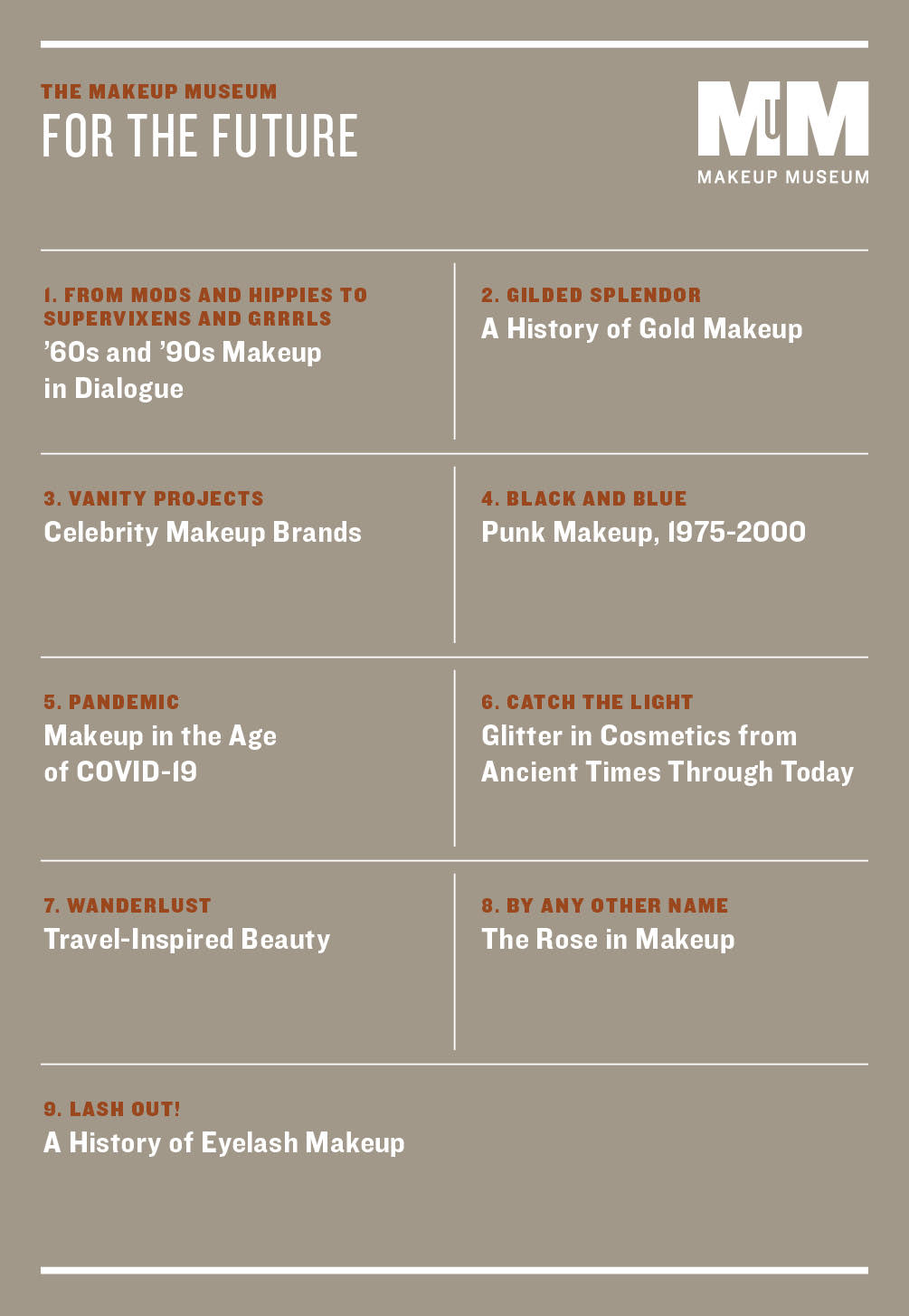

And the last set, which are things I'm still debating or that need to wait a bit.

- "From Mods and Hippies to Supervixens and Grrrls: '60s and '90s Makeup in Dialogue"

- "Gilded Splendor: A History of Gold Makeup"

- "Vanity Projects: Celebrity Makeup Brands"

- "Black and Blue: Punk Makeup, 1975-2000"

- "Pandemic: Makeup in the Age of COVID-19" – Sorry to everyone who thinks COVID is over, but it's not, so this is sadly remaining tabled.

- "Catch the Light: Glitter in Cosmetics from Ancient Times Through Today"

"Wanderlust: Travel-Inspired Beauty"

- "By Any Other Name: The Rose in Makeup"

Poor little neglected blog! I just can't seem to balance it with the bigger projects like papers and book chapters. I am aiming for at least 15 posts this year, but once again, I can't make any promises.

MM Musings (1-2): The next installment will be about problematic objects and how/if to display them. Museum accessibility and revisiting permanent collections and the issue of ethics in collecting are still up there too. I've also been dipping my toe into material culture and design history, so maybe something about the materiality of makeup objects.

Makeup as Muse (1): Oof. No Makeup as Muse in 2023. In addition to last year's shortlist of Janine Antoni, Rachel Lachowitz, Asa Jungnelius or Tomomi Nishizawa, I'm now looking at Anika Leila and Caroline Zurmely. I was also thinking that if the Museum should ever have a physical space, we could hold painting classes where people would bring in their expired makeup (or use some provided by me, LOL) and be their own Makeup as Muse. And of course I'd still love to do a whole exhibition on Makeup as Muse artists.

MM Mailbag (2): Again, none in 2023, so at least one this year would be helpful! Would also like to return to Dream Teams.

Vintage/brief histories (4-5): Mostly the same as the past two years, but more ideas popped up later in 2023, which are: oshiguma, Chinese beauty advertising of the 1920s and '30s, MCM design (had way too much fun with Art Deco last year!), the "multicultural" wars of the '90s, and histories of Femme Arsenal, Agnes Sorel, Xanadu by Faberge, Eddie Senz, Alo Cosmetics and Mona Manet Cosmetics. Really need to work on local (Baltimore/Maryland) beauty history too. And while I didn't get to it for this year's National Denim Day, I'd like to write something about makeup and healing from sexual assault (and while it's unrelated to the purpose of National Denim Day, there is a lot of denim-themed makeup.) To save you a click, here are some ideas from previous years: cosmetic practices of various Indigenous peoples, ear makeup, mouches and skin tone, true crime and makeup, a history of face gems, bindis, matching portraits on vintage compacts, the art of shibayama inlay, makeup for glasses wearers, spray (airbrush) makeup, Russian cosmetics during the communist era, guns and makeup, Riot Grrrl makeup, vices in makeup divided into 4 subjects (gambling/casinos, smoking/cigarettes, junk food and alcohol), dolls and makeup, histories of early modern powder applicators, setting sprays and color-changing cosmetics, copycats, profiles of some more obscure makeup artists from the '60s through the '90s, and histories of defunct brands (a slew of celebrity lines, Inoui ID, and revisit Stephane Marais), especially Black-owned brands like Marva Louis and Rose Morgan.

Continuations: Still need to finish up posts on Dorothy Gray's portrait series, Chinese makeup brands, and clothing and color coordination.

Topics to revisit (1-2): Mostly the same as 2022 and 2023 sadly, since I still did not tackle them: faux freckles, non-traditional lipstick shades, and a deeper dive into surrealism and makeup. I also need to do updates of both the mermaid exhibition and the Stila girls exhibition. 😉

Artist collabs (5): If you thought last year's list was overwhelming, it grew again in 2023. Additions include Aya Mobadeen for Bare Minerals, foxco for Clarins, Nicolas Lefeuvre for Shu Uemura, Elzbieta Radziwill for Sisley, the Eeni Edit for Ulta, Elizaveta Porodina for Addiction, and the Lancome Louvre collection. And already in 2024 there are a few: Margot Reverdy for Clé de Peau, Masaru Suzuki for Etvos, and Kerri Rosenthal for Bobbi Brown.

Book reviews (2-5): The list continues to be staggering. Take a peek at the Beauty Library and let me know what you'd like to see a review for.

Fashion: Off-White, Lauren Goodday for Prados, Marco Ribeiro for Pleasing, Sabyasachi and Shuting Qiu for Estée Lauder are the priorities, along with couple of vintage brands (Diane von Furstenberg, Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger, and Henry Rosenfeld).

Color Connections (1-2): Slowed down from 2023, but still keeping up with them!

Tabled for now: history of colored mascara, how makeup language has evolved (for example, why we typically say "blush" now instead of "rouge" for cheek color, the idea of makeup as jewelry, day and night makeup, wear-to-work makeup from the 1970s-90s, profiles of Halston, Calvin Klein and Nina Ricci brands, BIPOC salespeople and customers in MLM companies, and makeup ad illustrators.

New series: the Collector Chronicles. This would be a series of interviews with other makeup collectors and maybe it could be expand to include collectors whose interests fall outside of makeup. I've met so many fellow collectors online and would love to hear more about their collections!

Miscellaneous: Same as 2023, but adding a catch-up on Shu Uemura holiday collections.

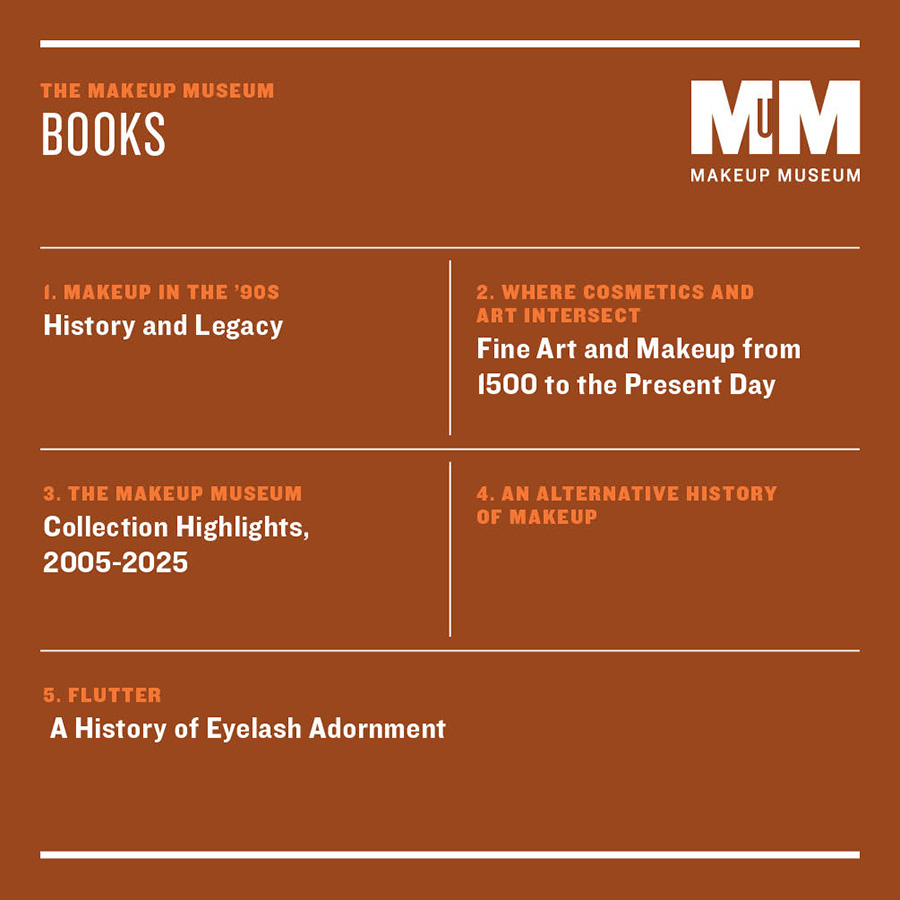

Books are the same as last year with one new idea: if there seems to be interest, I could see the Flutter exhibition becoming a book. I finally got around to reading Zahra Hankir's excellent Eyeliner: A Cultural History and I was really inspired! I think a history of eyelash adornment in a similar format could be useful too.

What exhibitions and blog posts do you want to see the most? And what do you think about lashes as the next exhibition topic?

It's roughly 6 months past the Makeup Museum's official anniversary back in August of 2023, but it's still technically the 15th year of the Museum's existence so I forged ahead with a small exhibition, the theme of which is the 15 most important objects in the current collection. I originally thought of doing my favorite objects, but let's face it, it would have just been all novelties, mermaids, artist collabs, and food-themed items. It was very hard to narrow down, as all the Museum's objects are important for one reason or another, but there is a good representation. All of them were chosen based on their historical, cultural or artistic significance. I was also sort of hoping it could serve as a prototype or precursor to a larger exhibition that would be expanded to include makeup styles and trends, along with other super important pieces that aren't yet in the Makeup Museum's collection – perhaps a global history of makeup in 100 objects? In any case, happy 15th to the little museum that could!

As with using electronic versions of the labels vs. taking photos of them attached to the shelves, I am puzzled as to why it took me 15 years to figure out it's much easier (and safer for the objects) to take photos when the pieces aren't on the shelves. I also figured I didn't need to re-take photos of objects that already have photos for blog posts or Instagram, so they all look a little different. Ah well. Here we go!

Top shelves, left to right.

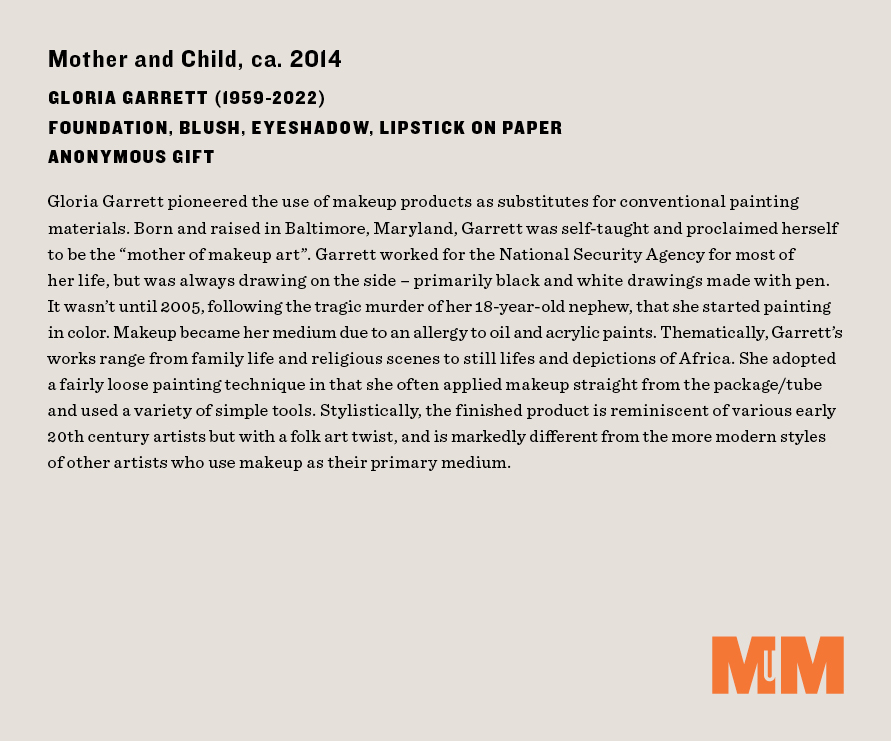

Mother and Child painting by Gloria Garrett:

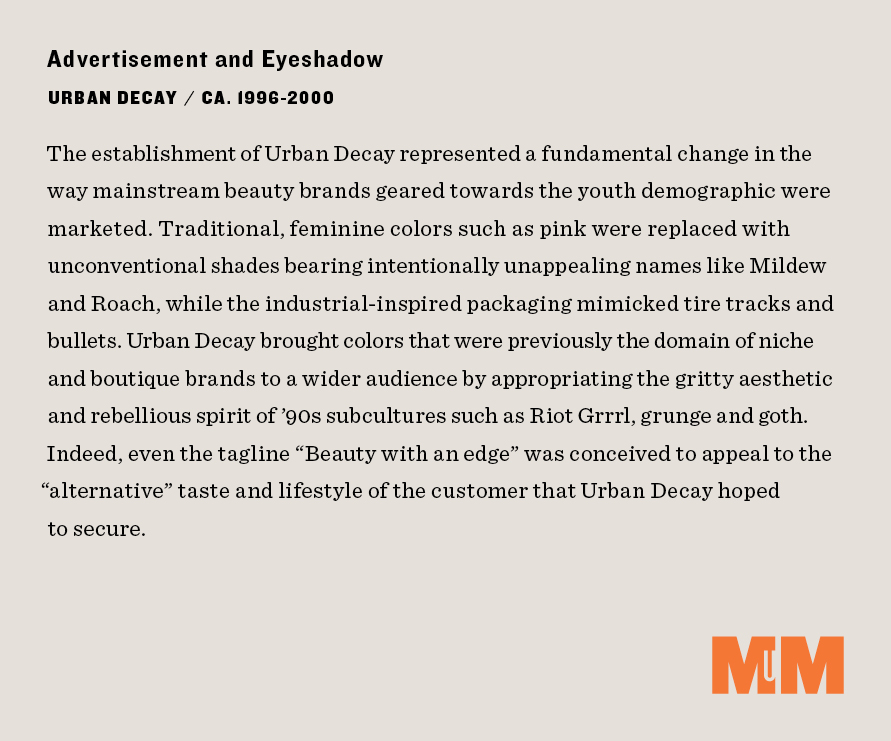

Urban Decay ad and eyeshadow:

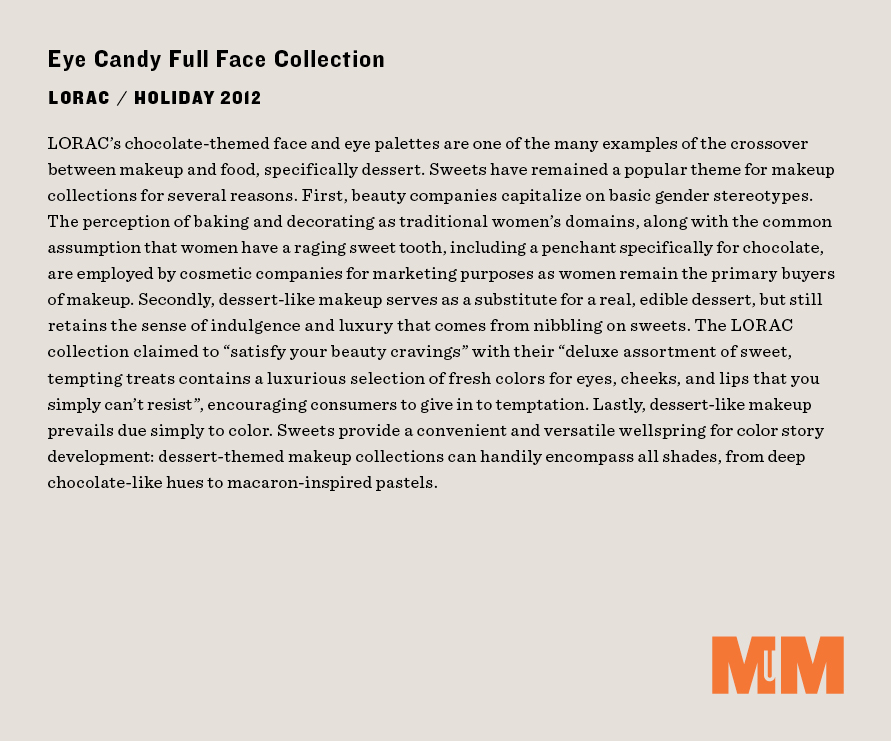

LORAC Eye Candy set – you might remember this from the Museum's 2013 Sweet Tooth exhibition:

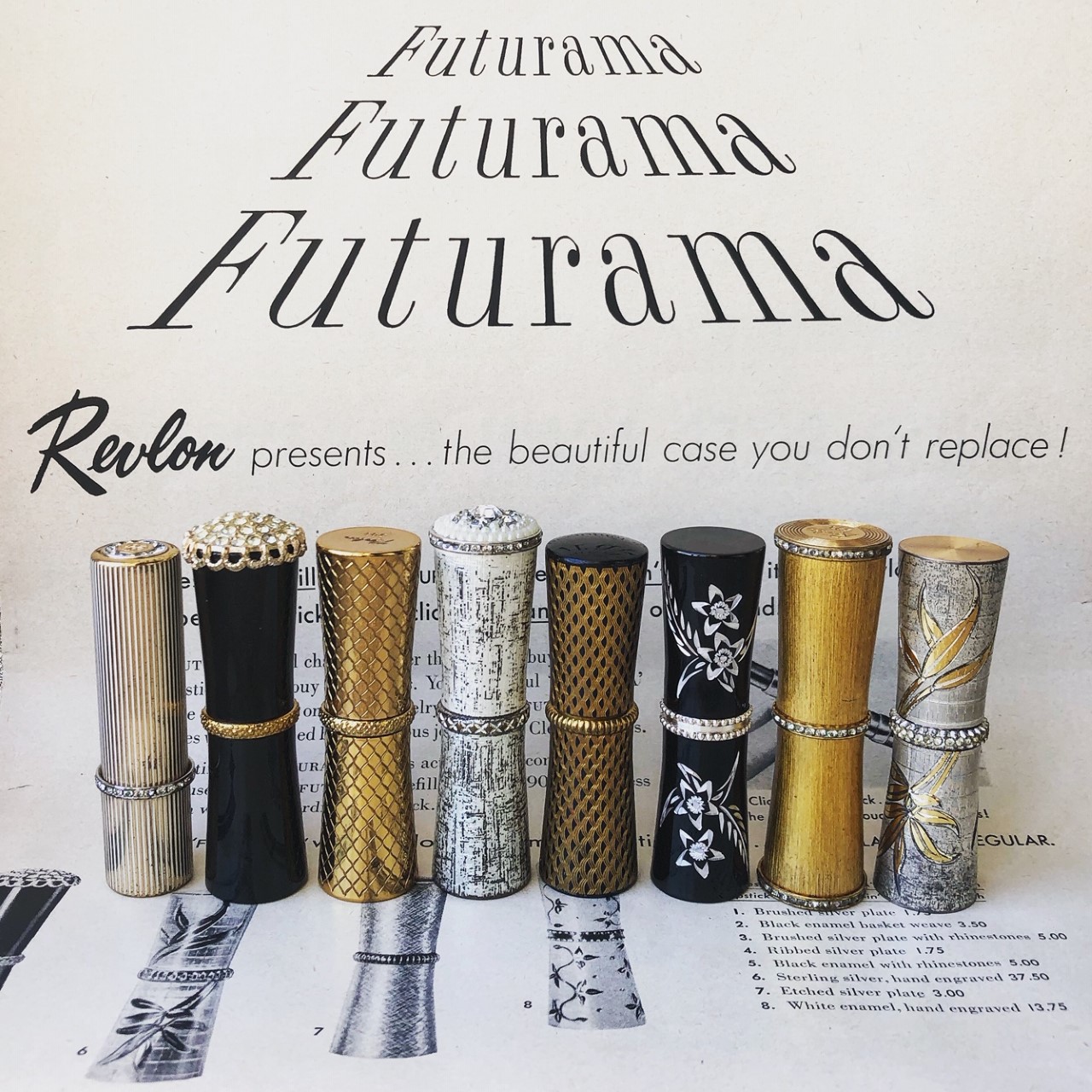

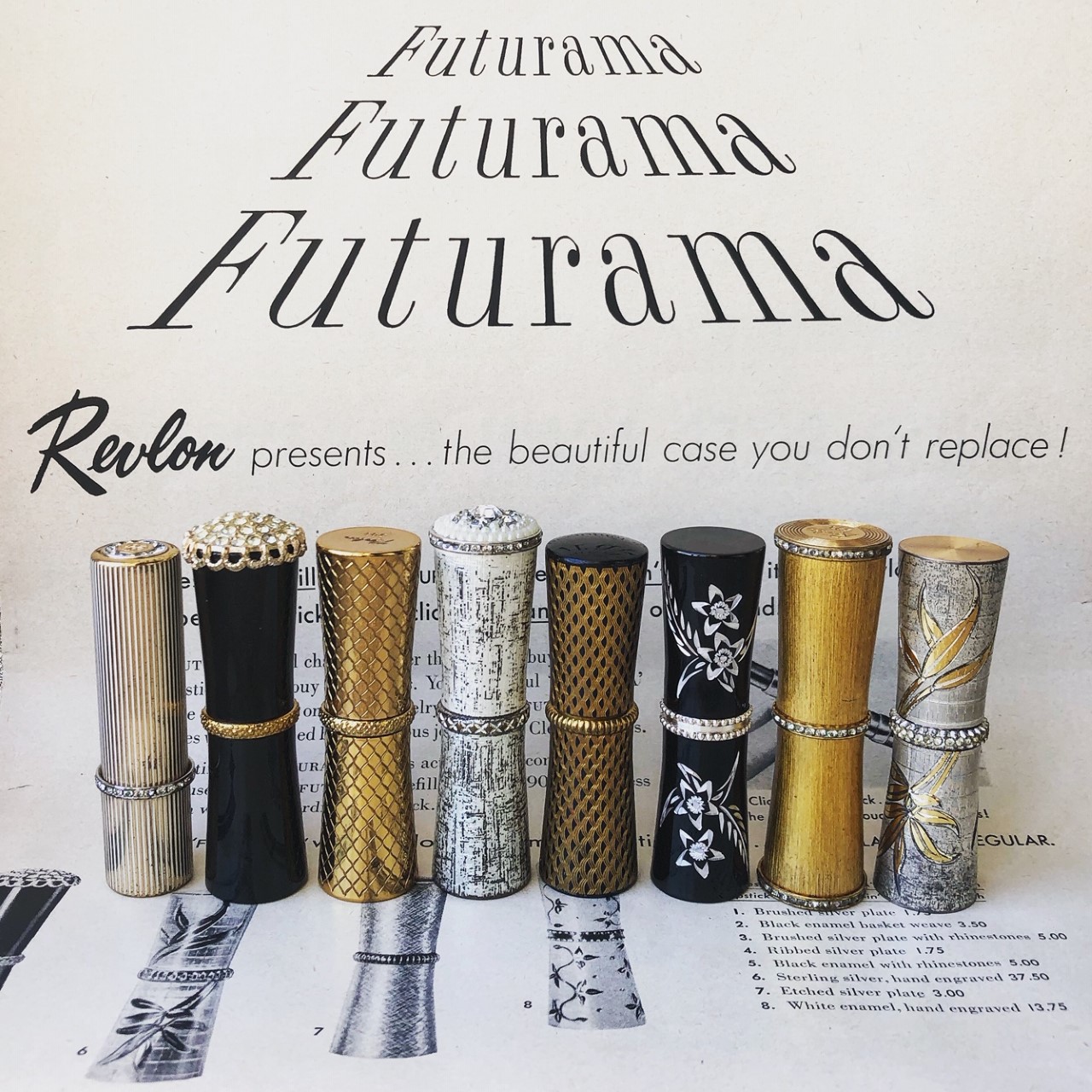

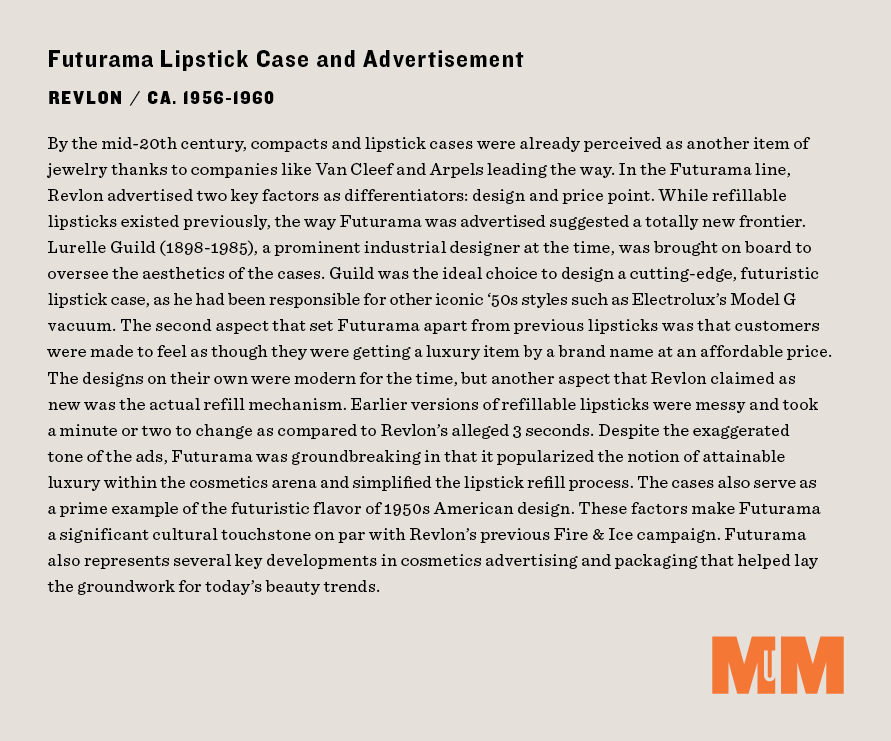

Revlon Futurama lipsticks:

Second row, left to right.

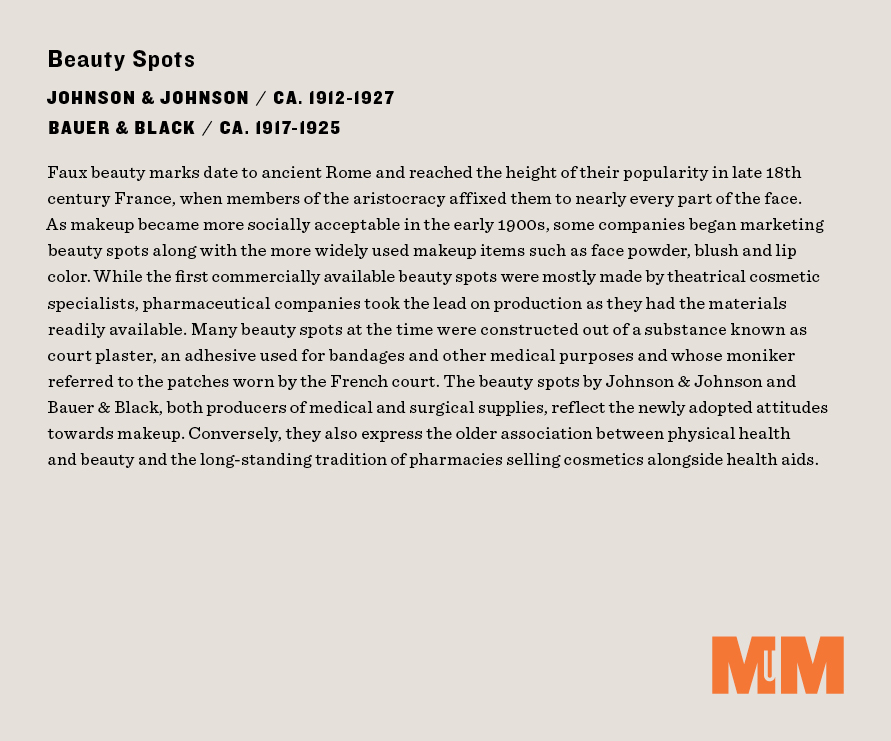

Beauty spots by Bauer & Black and Johnson & Johnson:

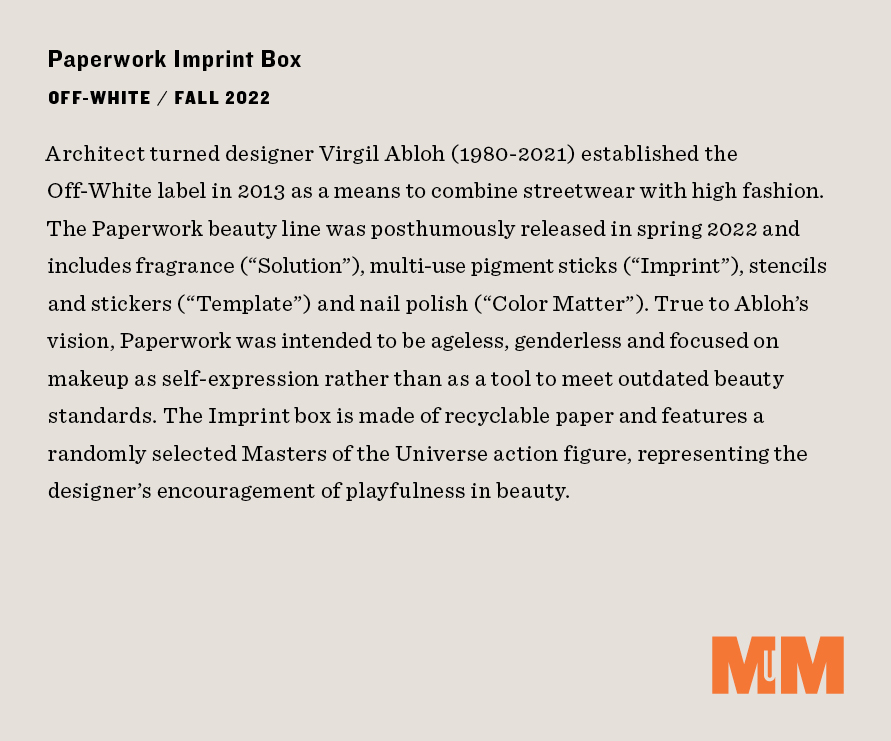

Off-White Paperwork Imprint Box…the box itself is absolutely ginormous so I just picked out a couple objects from it.

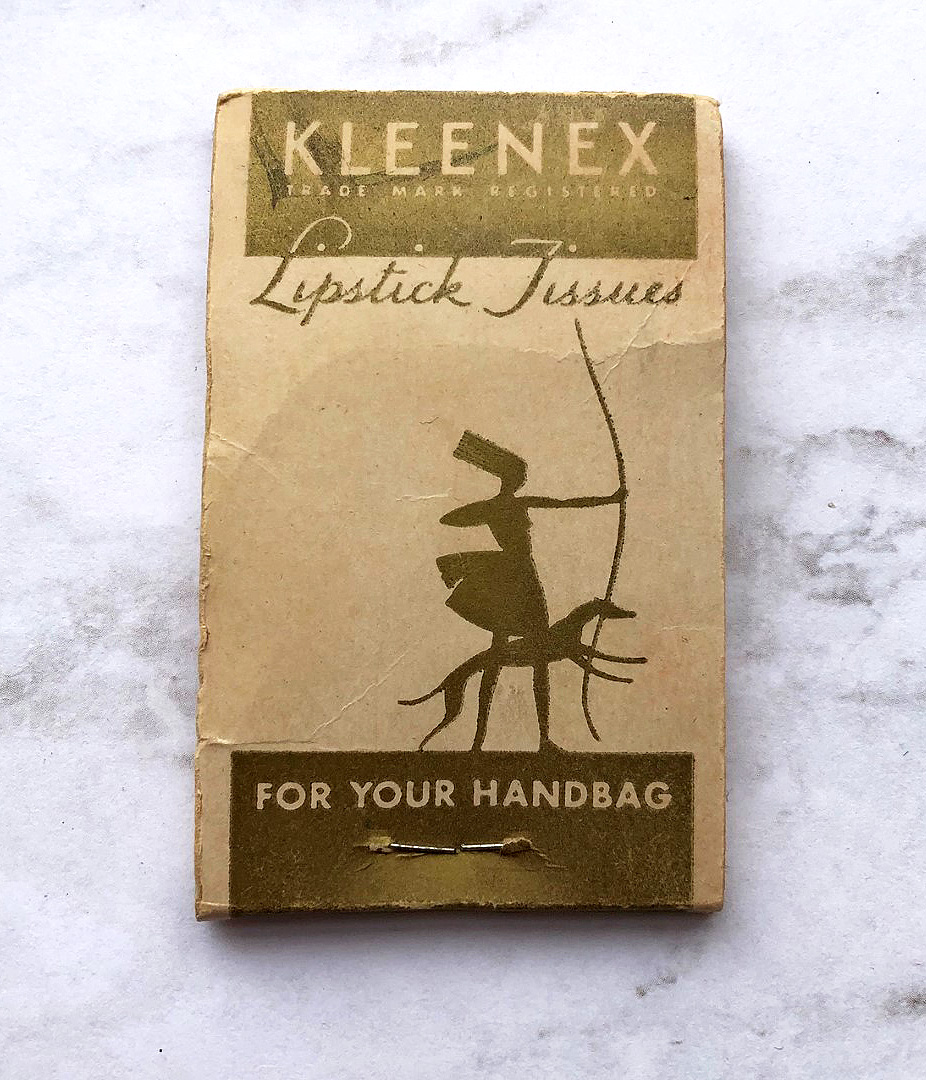

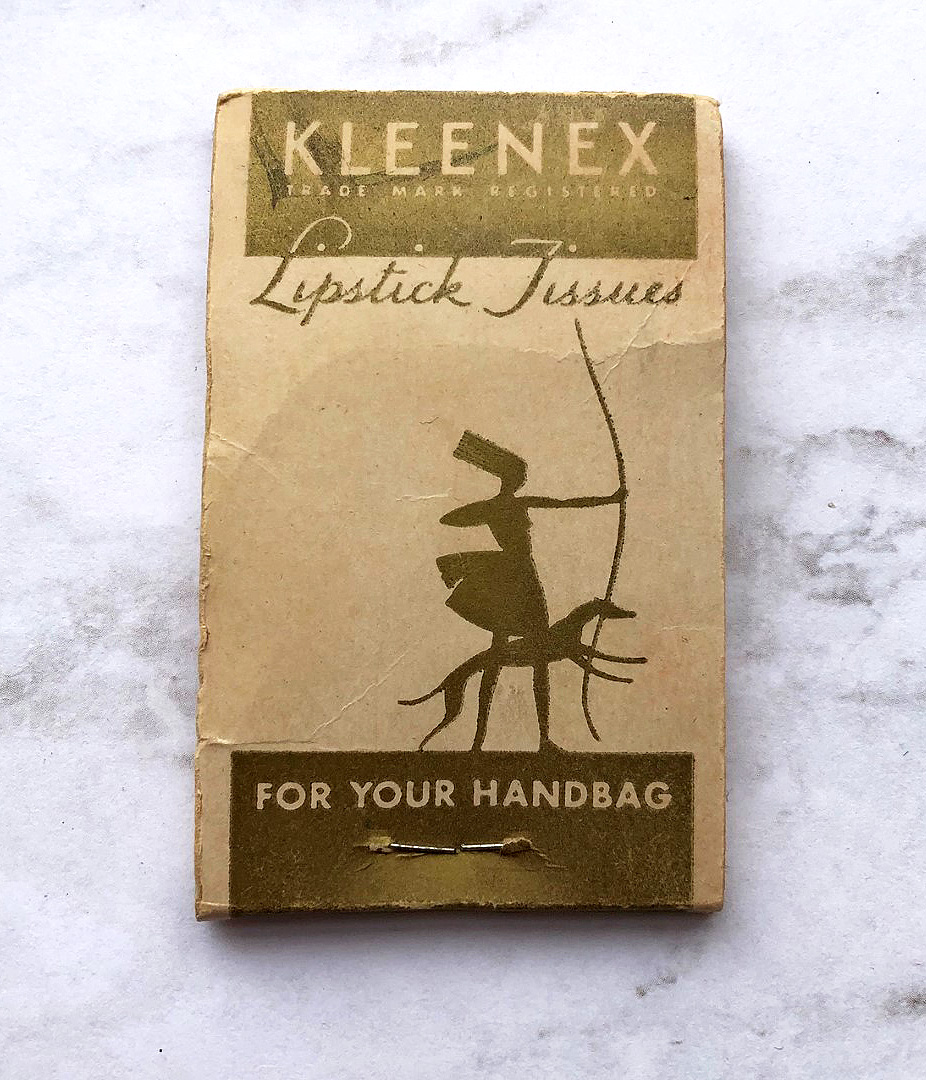

Lipstick tissues:

Kohl tube – this was a tricky one! I purchased it on eBay from a seller in India, but I suspect the lettering on the cap is Arabic, not Hindi, so I'm wondering if it really was made in India. I tried running it through Google Translate for images but the translation didn't make any sense. Update, 4/22/2024: Nadja, the brilliant genius behind the best art history podcast ever, kindly translated this! It is indeed Arabic and the word is simply "Arab". Also, there is an illustration of the exact same design on p. 144 of Jolanda Bos' Paint It Black: A Biography of Kohl Containers. That one is in the Musée du Quai Branly and has an accession date of 1982, so we know this design goes back at least to the early 1980s. The provenance for that one is listed as Jordan. All in all I'm guessing the fish-tail design is pretty common throughout the Middle East and India.

Third row, left to right:

Eihodo brush:

Helena Rubinstein Mascara-Matic:

Overton's face powders:

This was a bonus object – since there are 16 shelves I figured I'd throw it in. Behold, the palette that started it all, which also serves as a reminder to check out the Stila girls exhibition. 🙂

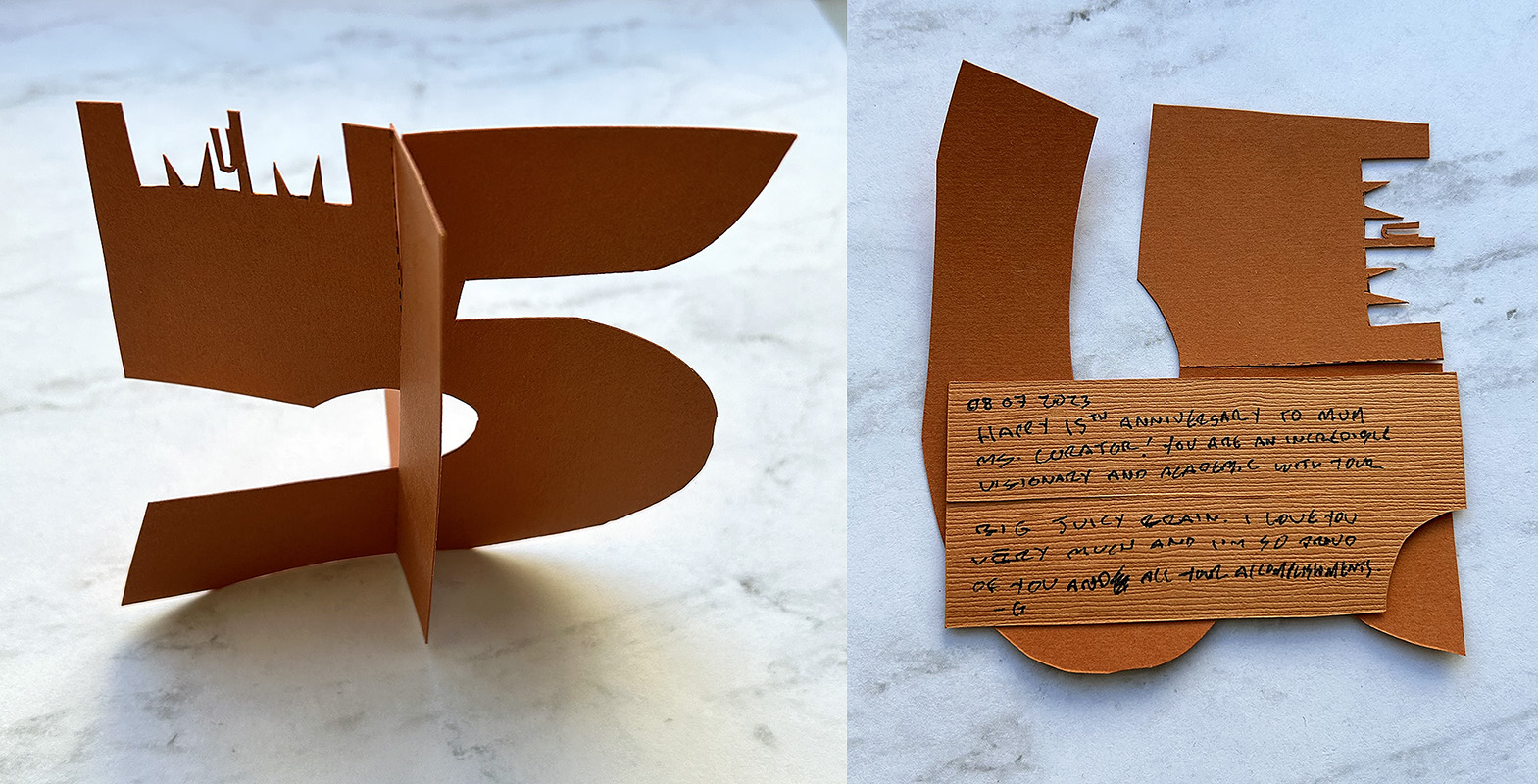

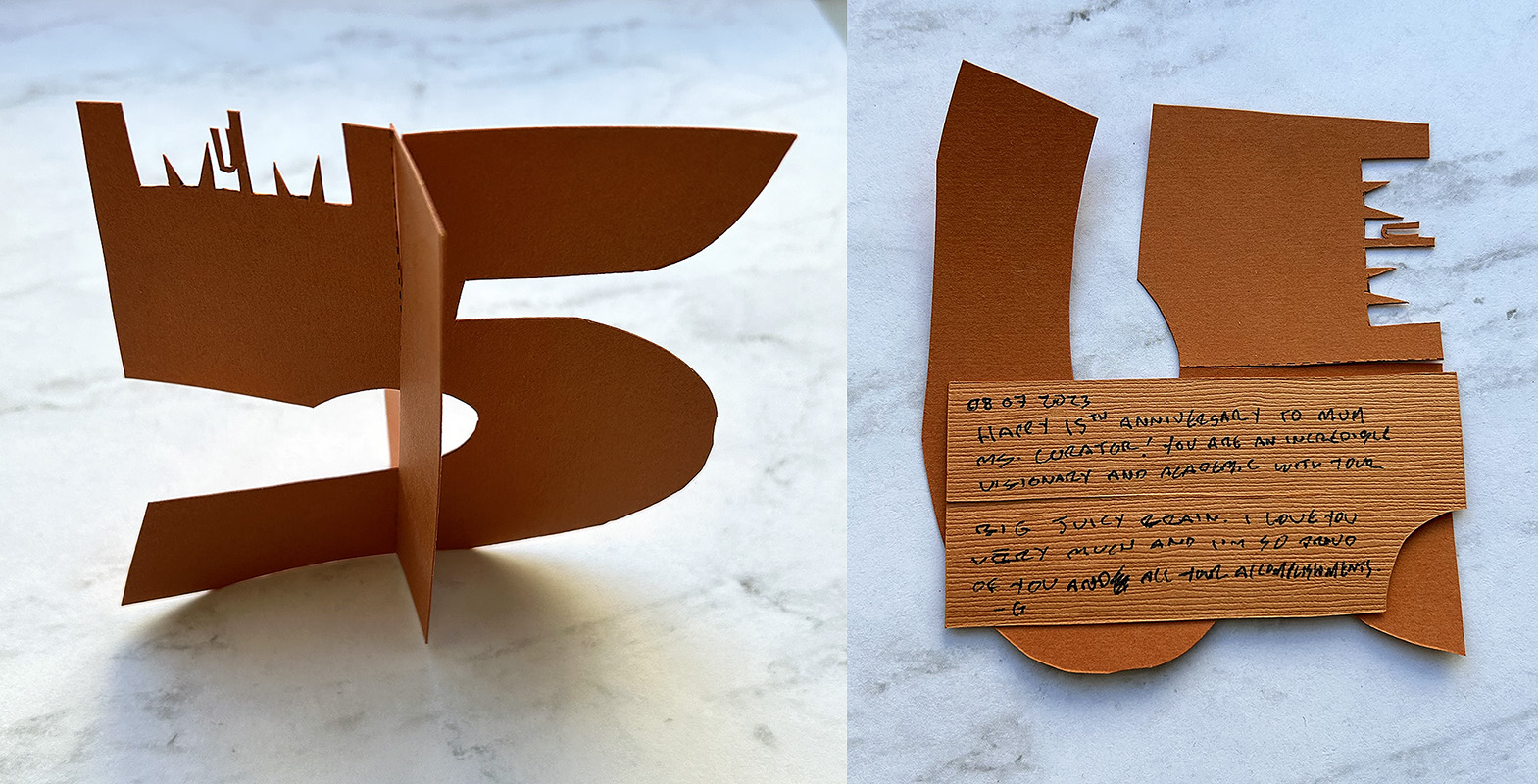

Plus, I had to show off the lovely card the husband made since it reflects all the support he's given me and the Museum since it started – he is a hugely important part of the Museum's history! It reads: "Happy 15th anniversary to MuM, Ms. Curator! You are an incredible visionary and academic with your big juicy brain. I love you very much and I'm so proud of you and all your accomplishments." Too sweet.

Bottom shelves, left to right.

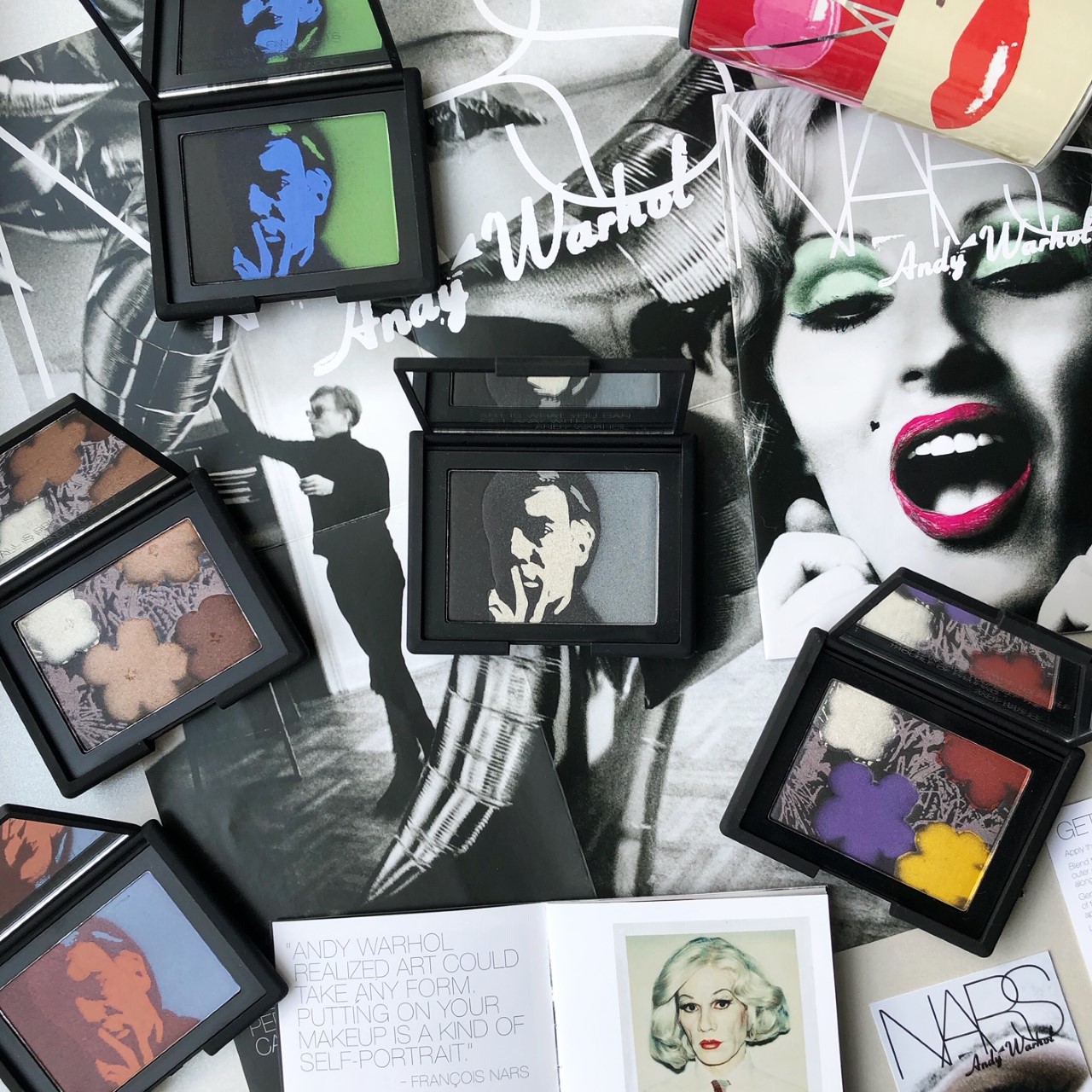

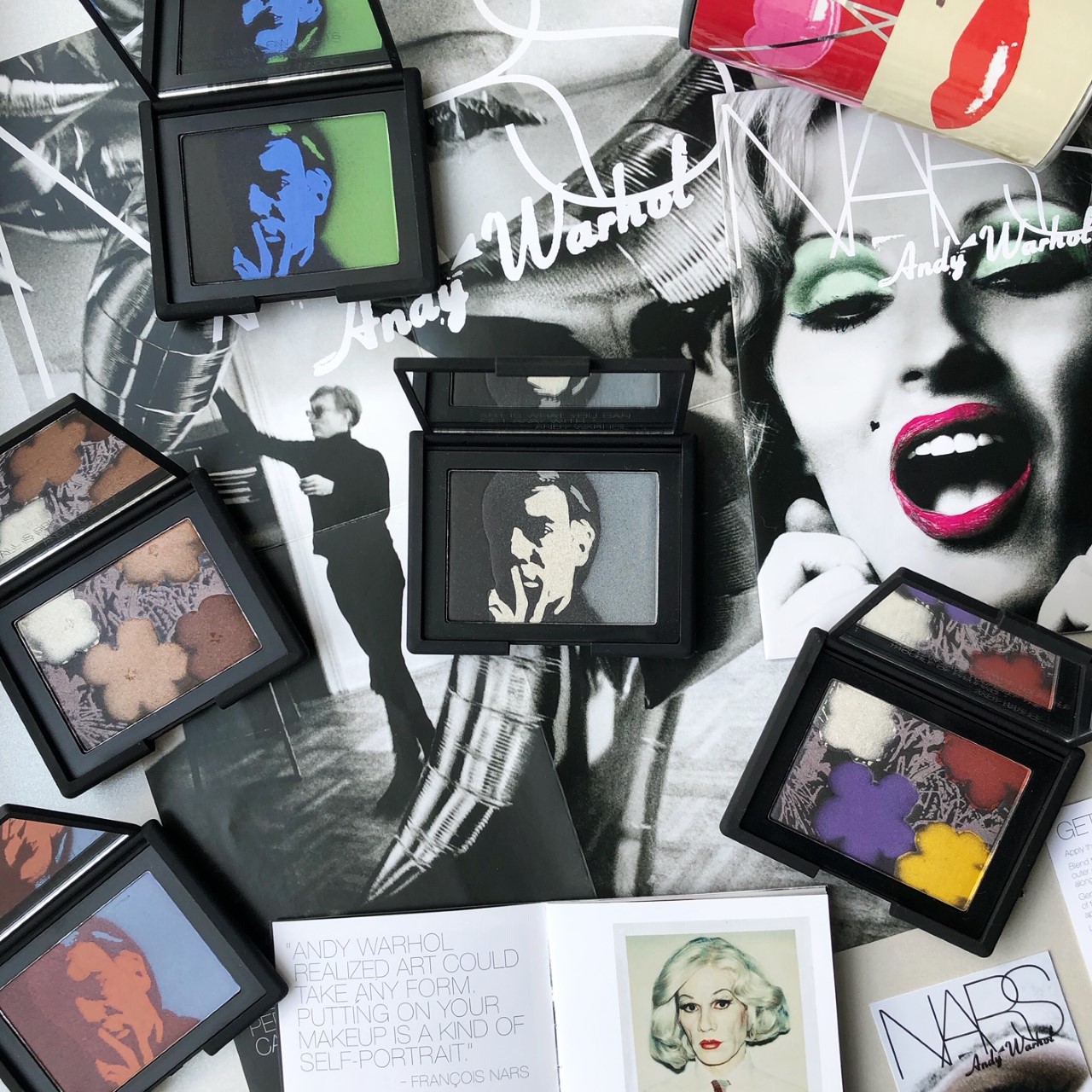

NARS Andy Warhol collection:

I thought long and hard about including these very problematic objects. Ultimately they made it in, not despite their overt racism but because of it. The next installment of MM Musings is going to tackle how, or even if, the Makeup Museum should display these sorts of pieces.

Etude House x BT21 palette and lip tints:

Beauty Palette compact, one of my personal favorites. And I know I mentioned all the photos are different, but these are particularly special – as you might have noticed, they are done by a professional! The Beauty Palette was one of 10 objects selected for test shots with the photographer I've hired. Professional photos are a critical part of collection digitization, so consider this a little sneak peek of the process.

In addition to an exhibition, this post also includes an informal history of the Makeup Museum as told by me, the founder and curator. 🙂

Very infrequently I get asked about the impetus for starting the Makeup Museum, so I thought I'd expand a bit on how it began. As stated in the About section of the website, the Makeup Museum was first envisioned as a coffee table book in the early 2000s. It was to be devoted to pretty or uniquely designed contemporary makeup. But I originally became interested in makeup packaging a few years before, in October 1999, when I spotted a cute Stila girl palette at Nordstrom. From then on I began collecting as much as I could afford. Two other factors contributed to this interest in packaging: meeting my husband in 2000, a graphic designer who showed me that everyday objects could be works of art; and the rise of embossed powders and artist collaborations. Up until the early 2000s, embossing wasn't widely used, and if it was, it was fairly crude and not the elaborate designs that came to be. Blogs and forums like Makeupalley.com, whose users often commented that some piece of makeup or another was "too pretty to use", made me think that there should be someone preserving these objects as art, and I loved artist collabs – it's an affordable way of owning a piece of their work, or at least a reproduction. I thought pretty makeup would be a perfect idea for a coffee table book, but the idea of getting it published was overwhelming, and a friend of mine told me to start a blog instead as blogs were at their peak in 2005-2006. As I was mulling that idea over, another hit me like a bolt of lightning: why shouldn't makeup have its own museum? I wasn't even thinking about vastness and importance of makeup history, only the aesthetics of current makeup packaging, but I thought that alone was worthy enough of its own museum. Plus, there really wasn't any specialized museum just for cosmetics in the U.S. Sure, fashion and design museums had a few vintage pieces and there were perfume museums, but nothing only for makeup. I wanted people to look at makeup differently, to see it in a way they hadn't before – not as a mere commodity but mini works of wearable art. I also was dismayed (as I still am now) that the vast majority of folks didn't see makeup as being worthy of a museum. I made it my mission to change their minds.

You can't tell me this isn't art! These all feature the work of women artists.

There was also a personal angle. At the time, I was heartbroken over not getting into doctoral programs and feeling quite lost professionally. I'll spare the sad details, but for a lot of reasons I was not able to carry out the career plan I had in college, which was to be an art history professor or museum curator. My thinking was that if academia and museums didn't want me, I'd start my own thing and have some kind of outlet that wasn't the mind-numbing tedium of administrative work, a.k.a. my day job. Like running a marathon, the Makeup Museum was admittedly set up mostly out of spite, a big ole middle finger to all the rejection I had endured. And it would be a place to both feed my brain and promote the idea of a museum as something other than walls and a static bunch of objects behind glass. Perhaps it was the topic of my Master's thesis that subconsciously inspired me too. Starting a museum with no real experience or resources was very much in the rebellious, DIY punk spirit of Riot Grrrl.

Can't believe it's been 20 years!

In September 2007 I registered the domain for the Museum – only for the dot org, since at the time, it was basically unheard of to register multiple domains for the same company or organization. I wanted it to be very clear the Museum was intended as a nonprofit, not a business or any other sort of entity, so the dot com, dot net, etc. were not registered (a decision that would prove absolutely disastrous over 10 years later.) I then spent nearly a year teaching myself HTML in an attempt to create an online museum, only to surrender in the summer of 2008 and implement the earlier idea of a blog. The three main blogging platforms were WordPress, Typepad and Google Blogger. I made what is in hindsight another unfortunate decision to go with Typepad. While it has served decently over the years, it would have saved so much time and money if the blog had been hosted at WordPress!

Over time, I started understanding the importance of vintage pieces and makeup history more generally. While I enjoyed pulling together seasonal exhibitions featuring newer items, they were lacking in a lot of respects: they weren't very complex and left out quite a bit of important history. The Museum was receiving inquiries on vintage objects and I felt as though an organization focused on makeup had a responsibility to include these in its collection. Social media was eye-opening as well in that the Instagram photos with the most likes were of vintage objects. In terms of research, I noticed so many disciplines (especially art history, my first love – I still try to keep up with the developments within the field) were getting "de-colonized" or going "beyond the canon", and I thought, wouldn't it be great if the Museum could do the same for makeup? While fantastic resources on basic makeup history exist, there is a significant lack of material on lesser known topics, and it seems much of makeup's history hasn't been written yet. I wanted to fill in the gaps, to tell stories about makeup that haven't been told before. This feeling definitely aligned with the Museum's original mission, which was to encourage people think about makeup differently. From about 2012 through 2018 the Makeup Museum experienced a slow evolution from a hobby dedicated to showcasing the newest and prettiest makeup to a more serious endeavor, one that shares an alternative account of makeup history and tackles current topics not covered in-depth elsewhere – but without losing sight of makeup's playful side. During this time I moved the materials for another hobby, making beaded jewelry, from the living room to offsite storage to make room for the Museum's ever-growing collection. While I don't remember the year, I do recall thinking that it was somehow symbolic: the Makeup Museum was no longer another past-time like beading, but a much bigger goal to which I would need to devote literally all of my time outside of work. To execute the vision I had in my head, I needed to give up some other things in my life and make it the highest priority. I have no regrets or resentment; I made that decision willingly. But it was going to be a lot tougher than I anticipated.

Stratton mermaid compact with one of my handmade necklaces

A major turning point came during a life-changing 36 hours in March of 2019. Between approximately 11am on March 17 and 8:30pm March 18, my world basically imploded. Once again I will spare the details, but the rest of 2019 was easily the worst time of my life to date. I was at a crossroads: should I keep going with the Museum or do I throw in the towel? It was the first time I seriously considered packing up the Museum for good. But for reasons I still can't totally explain (outside of my own stubbornness and again, rage/spite) I decided to stay with it. And not only keep going, but make the Museum the best it can be despite all the obstacles and lack of resources.

Around 15 months after those fateful March days in 2019, the U.S. experienced a major racial reckoning. I realized the total lack of diversity and inclusiveness was not at all what I had envisioned for the Makeup Museum, and with that, I began researching ways to alleviate this massive blind spot as much as I could. I also began paying more attention to the other negative aspects of makeup and its history. I don't think I ever shied away from it, but I felt taking a deeper dive into the problematic side of both makeup and museums was critical to the Museum's mission of education and its new focus on helping to effect social change.

In the past 5 years the Makeup Museum became an official nonprofit organization, was awarded a grant, and registered its name as a trademark. And soon there will be a brand new website complete with a digitized collection. I also co-founded an international network for academics and researchers whose work centers on cosmetics. I like to think these achievements help prove the Museum's legitimacy to the naysayers and firmly establish makeup's place as a field of study. For the Makeup Museum specifically, they demonstrate the ability to go from an escapist fantasy and repository for pretty things to a hybrid organization that combines education and exhibitions with activism. My biggest hopes are for the Makeup Museum to re-conceptualize the traditional museum model and lead the way in new academic areas for cosmetics. Ultimately, I would love for the Museum to be a showcase for exhibitions and a soundly researched and comprehensive permanent collection, but also a gallery where makeup artists and other visual creatives can display their work, a research institute, a community center where people can engage in workshops and discussions about makeup, and a space for activism. I also dream of a "beauty pantry" of sorts, where people in need can come and take whatever they want. This post is long enough so I'll expand on these ideas later. 😉

If you're still reading, thank you for joining me on this journey through the Makeup Museum's evolution and I hope you enjoyed the 15th anniversary exhibition!

I was trying in vain to catch up on some beauty news many moons ago and came across this article at Who What Wear – yet another on the history of red lipstick. There were a lot of things that bothered me about it, but the number one offense was the doubling down on the myth of Elizabeth Arden handing out lipstick to suffragettes during a 1912 march in New York City. After recognizing this claim’s veracity was murky at best, the article’s author stated, “I wanted to know more, so I went straight to the source: Elizabeth Arden, the very same global beauty brand founded by the namesake cosmetics maven.” A brand can certainly be used as a source, provided there are legitimate historical records that serve as evidence for their claims. However, in this piece there were many statements made by Janet Curmi, VP of global education and development at Elizabeth Arden, without anything to back them up. “On November 9, 1912, 20,000 women took to the streets of New York to advocate for the right to vote. Elizabeth Arden, a dedicated suffragette herself, opened the doors of her New York spa to hand out her Venetian Lip Paste and Venetian Arden Lip Pencil, before joining the suffragettes marching down Fifth Avenue as a sign of solidarity. The most striking sight was the bold red color on the women’s lips.” The accompanying photo shows suffragettes marching at the May 4, 1912 event (not November)…with nary a one wearing visible lip color. Just for funsies I reviewed some news coverage on the November march.* As with the May march, they describe quite a few details, including the exact route and the women’s clothing, but lipstick is not among any of them.

I am very interested to know where Curmi got this information. Arden wasn’t, in fact, particularly known as a “dedicated suffragist.” The legend of her providing lipsticks to marching suffragettes goes back to at least 1999 and names the May 4 rally (see Lucy Jane Santos’s outstanding effort to unravel its history, along with my findings), so November 9 appears to be a new twist on the mythos. Another addition is the reference to Venetian Lip Paste and Pencil specifically being given to suffragettes. As far as I can tell, no particular products were mentioned in the Arden suffragette story until 2021, when author Louise Claire Johnson published a book entitled Behind the Red Door: How Elizabeth Arden’s Legacy Inspired My Coming-of-Age Story in the Beauty Industry. Johnson states that Arden provided Venetian Lip Paste and pencil to the crowds at the November march, but does not cite an exact source: “However, six months later, on November 9, 1012, Elizabeth could no longer sit idly by in silence. Shuttering the salon for the day, she took to the streets and joined 20,000 women, double the size of the previous parade, and advocated for the right to vote. The most striking sight was the bold red color on the women’s lips, as they vibrantly spoke their truth. Elizabeth weaved among the masses handing out her Venetian Lip Paste and Venetian Arden lip pencil in deep red – the original ‘lip kit’. In history, it is often the slightest gestures that become revolutionary. The red lip kits were small, yet mighty weapons – a red pout in place of a middle finger against the patriarchy. Red lips were still considered illicit and immoral, so the women wore them in unison as a rebellious emblem of emancipation. Makeup was no longer a sign of sin but of sovereignty.” (p. 63-64)