I thought for sure Addiction's spring 2017 compacts featuring the work of Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) would be unattainable, as they were only available as a gift with purchase in Japan. Fortunately a seller I frequent was able to get both for me! I had heard of af Klint before and was intrigued by her work since I have a soft spot for colorful abstraction, but this collection made me admire it even more. I really have no idea how the collaboration came about as the description at Addiction's website is pretty vague: "We learned that a woman had painted these magnificent paintings at the beginning of the 20th century and wanted to know more about her." In any case I really enjoyed learning about af Klint and I hope you do too.

Much has been written about the artist, although that's a recent development due partially to the fact that af Klint stipulated that a group of her most significant paintings not be revealed to the public until 20 years after her death, fearing that they wouldn't be understood. In fact, it took even longer for her work to be recognized; it wasn't until a major exhibition in 1986 that her name was on the art history map, so to speak, and I'm guessing this was also due to the patriarchy at work. I don't want to spend much time reviewing her entire oeuvre, since I am not an expert and also because af Klint was a prolific artist, producing over 1,000 works (!) in her lifetime. I'll provide a brief bio and then focus on the paintings reproduced on the Addiction compacts. (Sources are linked throughout.)

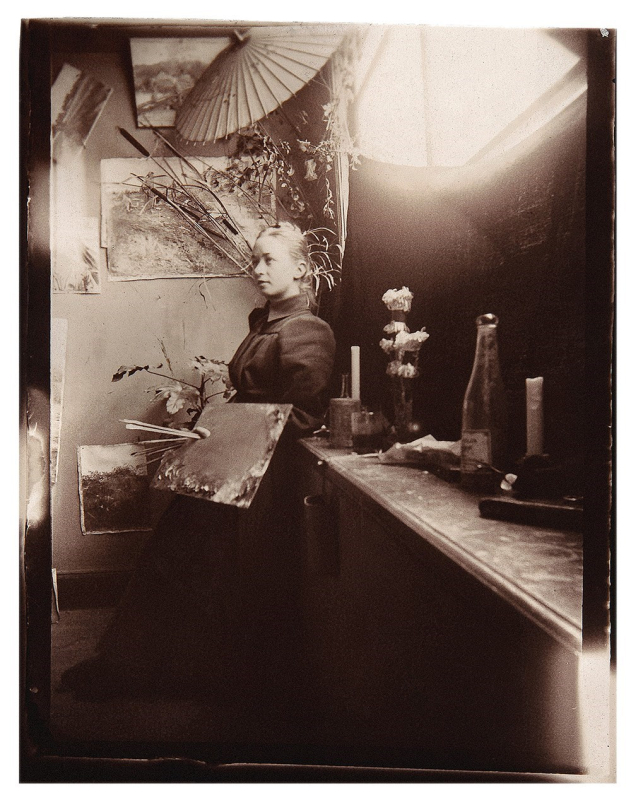

Af Klint was born in 1862 and entered the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 1882. This was a rarity for the time, as the art schools in most European countries allowed only men. While producing the usual landscapes, botanical and animal drawings – af Klint was a vegetarian and animal-lover who worked as a draughtswoman at a local veterinary school – she had started experimenting with abstract designs before she graduated in 1887. Af Klint, along with her contemporary Edward Munch (who, incidentally, once had a show in a gallery in the same building as her studio) were inspired by recent scientific developments involving phenomena unable to be perceived with the naked eye. Hettie Judah at The Independent explains: "This was a period in which the 'unseen' world exerted a growing fascination – not only the emotional, experiential world of the human spirit explored by Munch, but the discovery of physical forces and elementary particles that formed the known world on a microscopic level. In the late 1880s Heinrich Hertz proved the existence of electromagnetic waves: in 1895 Wilhelm Roentgen discovered X-rays. A vision of the world pulsing with forces and transmissions invisible to the naked eye was emerging." Af Klint's interest in abstraction was also influenced by her spirituality – having attended seances since the age of 17, she was greatly intrigued by the spiritual realm, and the death of her 10-year-old sister in 1880 only intensified her interest in the occult. In 1896 she formed a group with 4 other like-minded women artists and together called themselves The Five. Roughly 30 years before the Surrealists, these women tried their hand at automatic drawing and writing. Talk about being ahead of the times! During one session in either 1904 1905 af Klint was "commissioned" by Amaliel, one of several spirits she claimed communicated with her, to create an extensive collection that would become known as The Paintings for the Temple. In af Klint's words, the spirit guided her to "execute paintings on the astral plane" to represent the "immortal aspects of man." Completed between 1906 and 1915, the collection of 193 large-scale paintings were divided into several thematic series that "convey[ed] the unity of all existence beyond the fractured duality of the modern world. Different series within The Paintings for the Temple relate to the creation, man’s progress through life, evolution, and the human soul as divided into masculine and feminine halves striving for unity." It was this collection that af Klint stipulated could not be shown until 20 years after her death, a decision influenced by the opinion of a prominent Swiss philosopher who visited af Klint in 1908 and speculated it would be at least another 50 years until people understood her art.

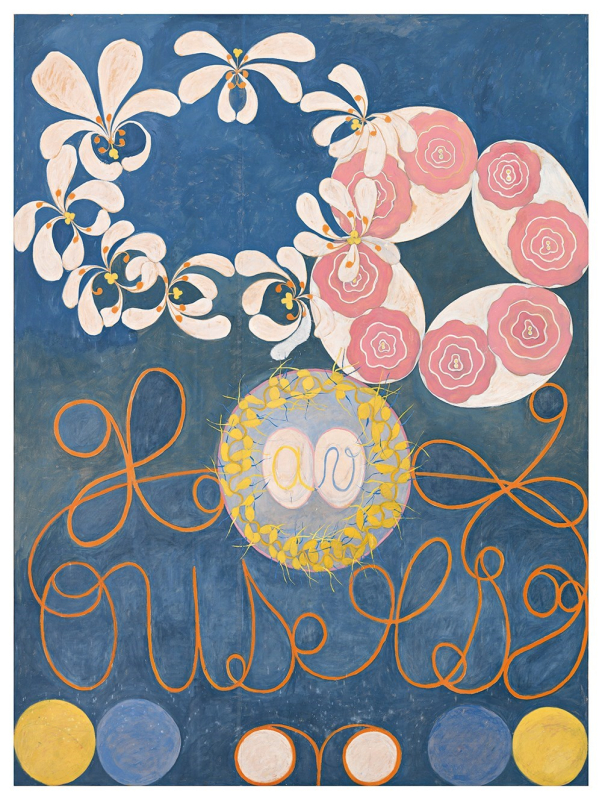

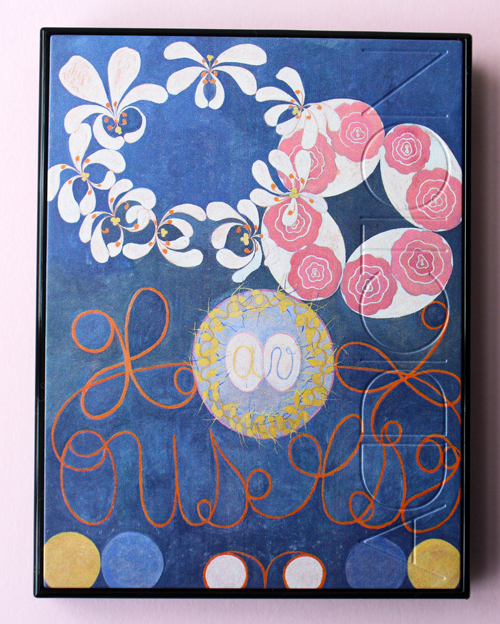

Anyway, The Ten Largest is the second series in the collection and was completed between August and December of 1907, quite a feat given their enormous size (10 feet tall) and af Klint's petite stature (5 feet). The Ten Largest traces the human life cycle in 4 stages – childhood, youth, adulthood, old age – and the two paintings chosen for the compacts are No. 1, Childhood, Group IV and No. 5, Adulthood, Group IV. Why Addiction selected these two in particular I don't know, but they do look lovely on the compacts.

Interestingly, af Klint noted that she wasn't all that aware of what she was painting, taking on the role of a receiver or medium. She explained, "The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brushstroke."

There's something so beautifully organic about these – they appear to be idealized representations of cells, flowers and other natural elements. I'll let the Royal Academy Magazine give a much better description: "Snail-shell spirals, concentric circles and zygote-like forms nestle amongst coiled fronds and splayed petals (she also produced intricate botanical drawings), all dancing against radiant tempera backgrounds from terracotta orange to faded lilac. Forms bulge, overlap, conjoin in what an eye informed by contemporary science might liken to celestial bodies or cell mitosis; they are extraordinary pictures, immense and ecstatic." The 26,000 pages (holy crap) of notebooks af Klint kept provide some clues as to the meaning of various colors and motifs. Blue and lilies symbolized femininity, yellow and roses stood for masculinity, and green was a universal color. The letter "U" designated the spiritual realm, while "W" denoted physical matter, and spirals symbolized evolution. This underscores that there was nothing passive about her process; in fact, she essentially studied her own work over the years, an example of which is a 1,200 page notebook that further analyzed the meaning of the images she had painted.

Here's the original so you can see how it's actually oriented – Addiction re-situated the paintings horizontally to better fit on the compacts.

(image from anothermag.com)

(image from anothermag.com)

(image from arteidolia.com)

(image from arteidolia.com)

Here are some of the eyeshadows. I have 4 of them but couldn't bear to take the plastic off, so I hope you'll forgive me for the tiny stock photos. I can absolutely see how the colors are inspired by af Klint. I guess they couldn't use the real names of the paintings, so some of them, like Flower Evolution, are merely reminiscent of af Klint's themes.

(images from addiction-beauty.com)

I'm really glad Addiction is helping to bring af Klint to a wider audience because for so long she didn't get the recognition she deserved. Five years before Kandinsky declared to have painted the first abstract work, af Klint was completing Primordial Chaos, the first collection in her monumental series. Some art critics claim that af Klint's paintings were merely diagrams of the spiritual world or depictions of scientific concepts we can't see, not true abstraction (or at least, a different form of the genre). That sounds plausible, but given that in 1970 the then-Director of Sweden's Moderna Museet turned down the offer of af Klint's entire estate because of her relationship to spiritualism and a more recent incident at MoMA in which af Klint's work was left out of an exhibition on early abstraction per the argument that it wasn't actually art, I'd say there's definitely sexism at work here. When you consider that Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich, etc. all drew inspiration from spiritualism and are heralded as the pioneers of abstraction, leaving af Klint out of the conversation seems blatantly sexist. When male artists borrowed spiritualist principles they were geniuses but when a woman did she was written off as a kook – not a real artist, just some crazy lady who happened to draw and paint a lot. Perhaps there's also an unconscious bias over the fact that af Klint subscribed to theosophy, an area of spiritualist belief that was founded by a woman and is notable for being the first European religious organization that actively welcomed women and allowed them to have senior positions. Additionally, the lack of renown could be the result of societal conditioning; women simply weren't encouraged to be at the forefront of art. Af Klint was no exception – as noted earlier, she worked largely in isolation and didn't participate in the avant-garde discussions going on in the rest of Europe. As Jennifer Higgie writes in Hilma af Klint: Painting the Unseen (p.16): "[…It's] irrefutable that although women artists were tolerated, they were rarely, if ever, encouraged to express the kind of radical ideas that marked their male contemporaries as innovators…even though af Klint was one of the earliest Western artists to wholeheartedly engage with abstraction, the most visible discussions of it as a viable new artistic language were conducted by men, all of whom were proficient at self-promotion." (Kandinsky was particularly known for puffing himself up.) In any case, I think these issues make it all the more important to acknowledge her work. Even if they're not "truly" abstract, af Klint's paintings are still vital to understanding the evolution of modern Western art. And when you consider the fact that she was producing these pieces in an atmosphere not exactly hospitable to women artists, it makes her accomplishments even more mind-boggling. Adrian Searle at The Guardian agrees: "Too often for it to be an accident, Af Klint had an innate sense of how to make a painting, often with no artistic models to turn to. Her best paintings are airy, their forms and geometries delivered with an evident pleasure and openness…The scale and frontality and freshness of her work still stand up, in a way that many Kandinskys don't. Yet looking at photographic portraits of the artist, we see a stern woman who was far from cosmopolitan, and in whom there are few outward signs of emancipation. For a woman to be an artist at all in Sweden in the early 20th century was difficult enough. To be an artist who believed as she did must have made matters even more difficult."

Anyway, I'm still trying to figure out how Addiction got the rights to use af Klint's work on the compacts. Having a collection inspired by an artist's work is one thing, but actual reproductions are trickier legally. There is a Hilma af Klint Foundation governed by her family members, so possibly they granted the rights to Addiction, but that would be a huge feat for the company to pull off since the guardians of af Klint's estate protect the use of her work rather fiercely. And of course there's the age-old question of whether a deceased artist would approve of their work being used this way. I really can't say in the case of Klint. On the one hand she seems like someone who wouldn't be interested in makeup – given that her life's work consisted of representing tremendously complex philosophical and spiritual ideas, she may have perceived cosmetics as frivolous. On the other hand, this may also mean she'd be okay with people enjoying her art in whatever format it appeared. Says Iris Müller-Westermann, Director of Moderna Museet Malmö, "This was really an artist who dared to think beyond her time, to step out of what was commonly accepted…she had visions about bigger contexts where it was not about making money or being very famous, but about doing something much more humble: trying to understand the world and who we are in it." Af Klint also seemed to believe that women should be equal, and part and parcel of equality is being able to express ourselves however we choose. I'm not able to paint on a canvas but I can get creative with makeup. I think af Klint would have appreciated that.

Overall I'm delighted with this collaboration. I am possibly the least spiritual person I know, but looking at af Klint's work I feel simultaneously curious about our place in the universe and incredibly at peace. I can only imagine how I'd react if I saw these in person; an anecdote from the blockbuster 2013 af Klint exhibition notes that many visitors cried when faced with af Klint's monumental works but couldn't explain why, something that's happened to me when standing in front of certain works of art. As for the Addiction collection, the colors and textures make me want to try to "paint the unseen" – just like af Klint but using my eyelids as a canvas!

What do you think? Had you heard of af Klint before now?

Wow, wow, WOW! Thanks for this! I was not familiar with Hilma af Klint (she wasn’t ever mentioned in my Women in Art classes in college) Her work and story are fantastic!

I agree with you that sexism probably played a part in the art world’s ignoring her, but her spiritualism probably did too. Male artists of the time who admitted inspiration from spirituality made sure to supersede it with their own analytical prowess – as much as I’d like to be inspired by Kandinsky’s “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”, I always find it woefully unsatisfying.

To admit that the spiritual side of life might be as powerful as some of us suspect it is – to risk being overpowered by it – and to act on it – is absolutely not in keeping with the “artist as sole creative genius” image that’s part of the art world.

But even if af Klint was the New Age Weirdo Chick of her community – I’m glad the paintings survived. I will be investigating her further!

Wow, wow, WOW! Thanks for this! I was not familiar with Hilma af Klint (she wasn’t ever mentioned in my Women in Art classes in college) Her work and story are fantastic!

I agree with you that sexism probably played a part in the art world’s ignoring her, but her spiritualism probably did too. Male artists of the time who admitted inspiration from spirituality made sure to supersede it with their own analytical prowess – as much as I’d like to be inspired by Kandinsky’s “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”, I always find it woefully unsatisfying.

To admit that the spiritual side of life might be as powerful as some of us suspect it is – to risk being overpowered by it – and to act on it – is absolutely not in keeping with the “artist as sole creative genius” image that’s part of the art world.

But even if af Klint was the New Age Weirdo Chick of her community – I’m glad the paintings survived. I will be investigating her further!

Hi Meli! Thanks so much for reading and for the thoughtful comments (as always). You raise some great points. And I do agree that even if she was a total nutjob, she was damn talented and I love her work.

Thanks so much again!!

Hi Meli! Thanks so much for reading and for the thoughtful comments (as always). You raise some great points. And I do agree that even if she was a total nutjob, she was damn talented and I love her work.

Thanks so much again!!