Welcome to the first of many, many, many artist collaborations this holiday season! I'm kicking them off with an unexpected collaboration between Urban Decay and artist Patrick Nagel. If you were an '80s child and/or had an older sibling who was into Duran Duran, Nagel's work might look familiar.

Here they are individually with their original artwork and open, in case you're not a crazy collector like me and want to actually use the palettes. 🙂

Patrick Nagel (1945-1984) was born in Dayton, Ohio and raised in Orange County, California. I'll just let his official website provide the rest of his bio: "After returning from his tour in Viet Nam, he studied fine art at Chouinard Art Institute and California State University, Fullerton where he received his BA in 1969 in painting and graphic design. He then taught at Art Center College of Design while simultaneously establishing himself as a freelance designer and illustrator with memorable ads for Ballantine Scotch, IBM and covers for Harper’s magazine. In the mid-70’s he began illustrating stories for Playboy magazine, bringing instant exposure and a large appreciative audience to his work. His years working with Playboy established him as the heir apparent to 50’s pin-up artist Alberto Vargas and gave Nagel the subject matter that he would continue to use to illustrate the newly liberated woman." And this is where I start rambling about Nagel's depictions of women so you're in a for a long, possibly boring ride. I simply don't think I can look at his work without debating some critics' premise that Nagel loved women.

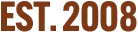

To get better informed on the matter, I purchased The Artist Who Loved Women by Rob Frankel, in which he uses Nagel's personal life to come to the conclusion that the women he painted were strong, fierce, powerful ladies in their own right. However, there are A LOT of details from Nagel's biography that lead to me to believe otherwise.1 The sticky notes in the photo below demonstrate all the instances where I found Nagel to be less than the champion of women he's perceived as in this book, along with where I take issue with Frankel's stance.

Why are Nagel's images of women so striking? Well, according to the author, their beauty is only important as it relates to the male gaze; their power comes from whether they're perceived as attractive by men. "There is one special moment in every man's life…it's that heart-stopping moment when he first beholds an incredibly special woman…her hair flows, her eyes sparkle, and she moves with liquid grace. She is everything he imagined his perfect woman to be…it wasn't the woman in the piece [of Nagel's art that the author purchased.] It was Patrick Nagel's ability to convey that special moment every man experiences – or hopes to experience – about the woman of his dreams. The Nagel Woman has no distractions; she is fully and completely dedicated to fulfilling her role as Nagel's ideal woman." (p. 15-16; 101). I mean, really? So apparently Nagel's depictions of women aren't actually about them at all, only (heterosexual) men's reaction to them. With this stance, it seems Nagel believed that women weren't worth painting unless they were able to capture his and other men's imagination – a female viewer doesn't fit into the equation at all, making it seem as though his images are merely eye candy for straight men rather than a representation of women who are beautiful and interesting in their own right.

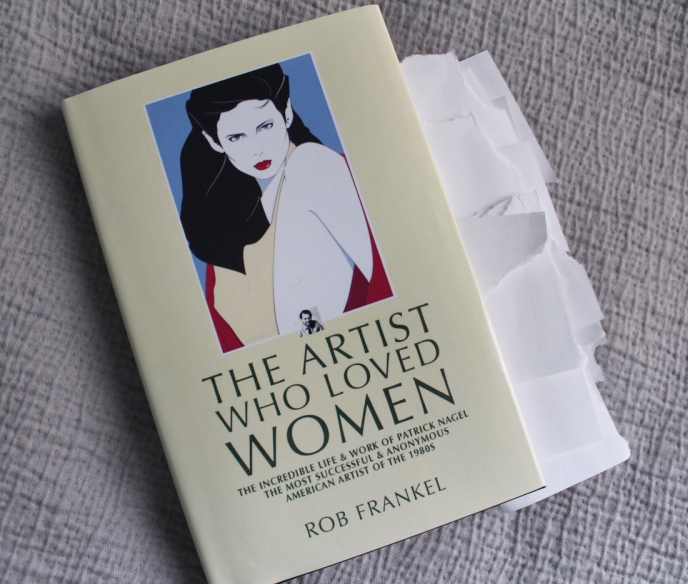

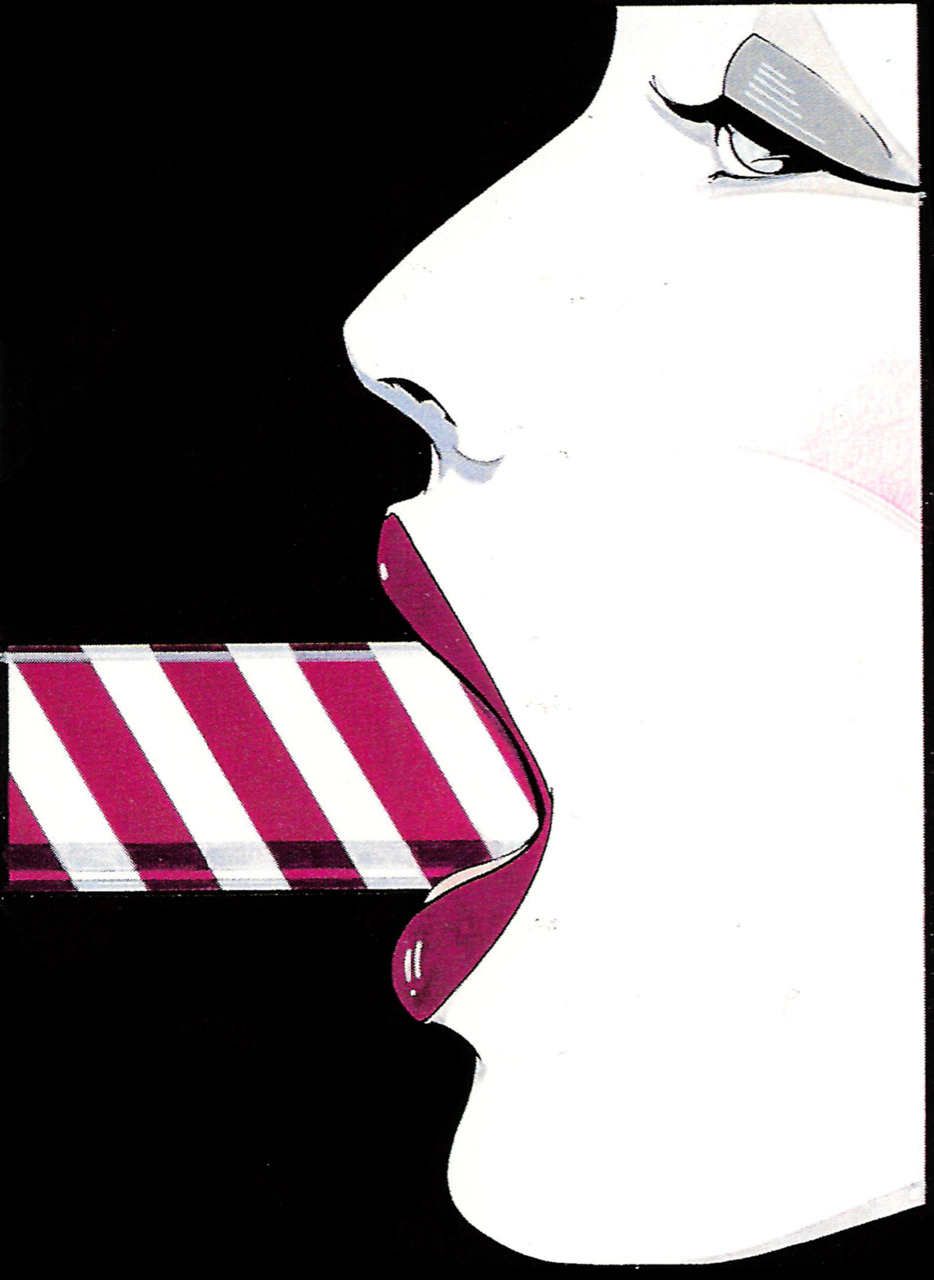

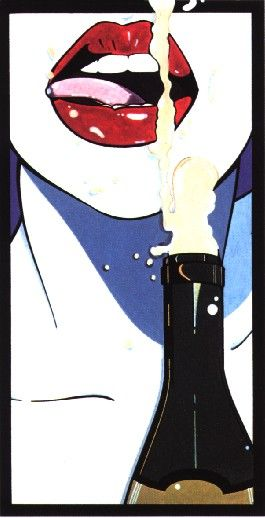

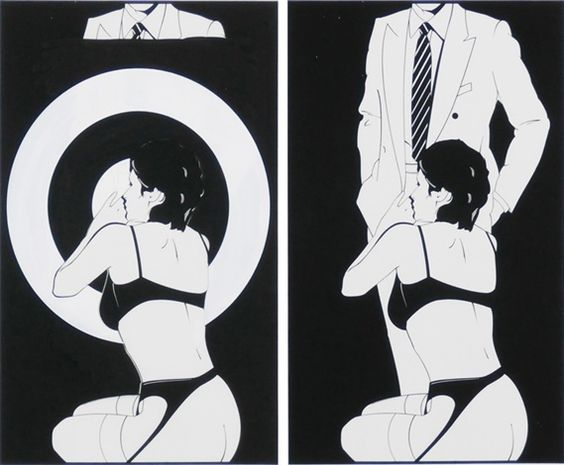

Secondly, I question whether anyone who contributes to Playboy in any capacity – Hugh Hefner (who, incidentally, held the largest private collection of Nagel's art and who also claimed to "love women") can rot in hell as far as I'm concerned – truly believes women are human beings and not objects whose value is determined by their ability to attract men.2 Insists Nagel's friend and assistant Barry Haun, "Often he would get out and buy the models outfits, usually bringing in makeup and hair stylists, too. The sessions were always very professional. You could tell that he loved women, being drawn more to their sensual qualities rather than to their overt sexuality." Uh-huh. I'll just leave these Playboy images here.

I don't see any "overt sexuality". Nope, not at all. *eyeroll*

(images from pinterest)

Based on another quote shared by Nagel's rather unscrupulous manager, Karl Bornstein3, I'm inclined to think the artist may even have been a bit judgmental of the women he drew. "The mystery of women was very important to him, and he held women in the highest esteem. But he said once, 'I don't think I want to know these women too well. They never come out in the sunlight. They just stay up late and smoke and drink a lot.'" This is rich coming from a man for whom cigarettes, candy, coffee, Pepsi, aversion to exercise and staying up all night summed up his lifestyle.4

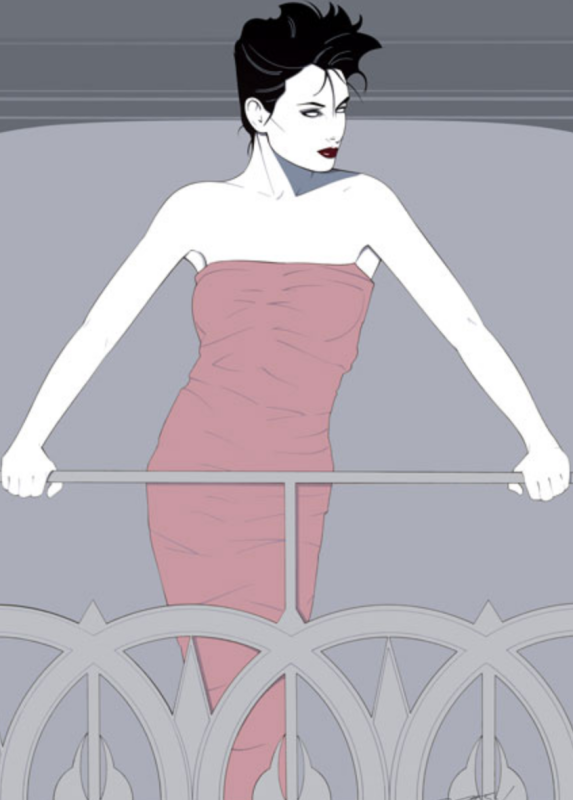

Having said all this, while Nagel's images for Playboy aren't screaming feminism to me, others from the '80s do seem to be more positive in the depiction of women. Perhaps the above quote could be construed as Nagel almost being intimidated by these fierce and fashionable ladies. And if we can separate the Playboy pieces along with Nagel's personal relationships and perception of women from the rest of his oeuvre, perhaps these women can be viewed in a very different light. Elena G. Millie, former curator of the poster collection at the Library of Congress, has this to say about Nagel's women: "She is elegant and sophisticated, exuding an air of mysterious enticement. She is capable, alluring and graceful, but also aloof and distant. You will never know this woman, though she stares out of the Nagel frame straight at you, compelling you to become involved, challenging you to an intense confrontation…His women of the seventies are shown as softer, more pliable, and more innocent than his stronger, harsher, more self-assured women of the eighties." Adds the author of the blog '80s Autopsy, "They didn’t need your approval — you needed theirs. Regardless of how long you stared at them, they remained unknowable – and unattainable." I'm inclined to side more with these interpretations than Frankel's.5

No matter what side you take regarding Nagel's women, it's undeniable that his work both captured and defined '80s style. While Nagel's work is totally different visually from that of his contemporary Antonio Lopez, both artists contributed enormously to the overall look we associate with the decade. As for Nagel's own artistic style, two distinct elements came into play: Japanese woodblock prints and posters from the late 1800s/early 1900s. (Remember that Nagel studied both art history and graphic design, and also did commercial posters for clients more PG than Playboy.) Millie explains, "Like some of the old print masters (Toulouse-Lautrec and Bonnard, for example), Nagel was influenced by the Japanese woodblock print, with figures silhouetted against a neutral background, with strong areas of black and white, and with bold line and unusual angels of view. He handled colors with rare originality and freedom; he forced perspective from flat, two-dimensional images; and he kept simplifying, working to get more across with fewer elements. His simple and precise imagery is also reminiscent of the art-deco style of the 1920s and 1930s- its sharp linear treatment, geometric simplicity, and stylization of form yield images that are formal yet decorative." I've chosen a couple images where I think the ukiyo-e, poster and Art Deco influences are strongest.

(images from patricknagel.com)

(images from patricknagel.com)

In terms of process, Nagel first made drawings from photos he selected, then created paintings from those. "His preliminary drawings for these designs are the exact antithesis of the final paintings. They are light, airy, ragged, and free. They are composed by line, but not confined by line. He would submit images for the client to choose from, subtly suggesting the product in the artwork. After the choice had been made, Nagel would then work up the finished painting, choosing the colors and lettering himself. He sometimes used as many as twenty-two colors per image…He felt that his drawings took him as far as he had to go with a design, yet his finished paintings are amazingly powerful images, rich with color and artfully imaginative. Finally, he would give the finished painting, along with a black line drawing, to the silk-screen printer for execution."

Now that I've done my due diligence in examining the content, style and process behind Nagel's work, let's get back to the Urban Decay collab. I really have no idea why the company decided to put this artist on their lipstick palettes. Obviously the licensing wasn't difficult to come by, as using Nagel's work for commercial purposes was, I'm guessing, another side effect of the mismanagement of his estate.6 This leads to the age-old question of whether a deceased artist would approve of their work being used to sell everything from makeup to t-shirts. Even though it's a question that can never be answered, I always like to explore this issue. It's hard to say in Nagel's case. On the one hand I think he would have been flattered to collaborate with Urban Decay, a brand which always prided itself on catering to badass women everywhere. If we interpret Nagel's art as being depictions of strong, powerful, DGAF women, the Urban Decay brand is a perfect fit. But based on what I read in his biography, I'm wondering whether Nagel might have been opposed to his art appearing on items marketed mostly to women – I get the sense that he would have approved his images for more traditionally masculine pursuits, like beer packaging or car advertising, since, as his biographer claims, the beauty of the women Nagel painted were solely for men's enjoyment. Along those lines, I bet Nagel wouldn't have been happy to see unlicensed prints and knock-offs being used at many a cheesy '80s beauty salon.

Anyway, while we can't answer that question or why Urban Decay chose to partner with Nagel, it's still an interesting collaboration. My enthusiasm was a little deflated upon reading Nagel's biography, but I'm choosing to go with my gut reaction upon first laying eyes on these palettes (i.e. before I knew anything about Nagel) which was that they represent some of the most quintessentially '80s art and were simply a celebration of fashionable women. Ignorance is bliss.

What do you think?

1 Other salient points to consider:

- Early in his career, Nagel abandoned his wife of 10 years and their infant daughter to pursue a more "glamorous" lifestyle in L.A., where he then married a fashion model several years younger. As she grew up, Nagel allowed his daughter a 2 week-long visit to his home in L.A. every summer, but never permitted her to call him "dad". Sounds like a real peach. There's nothing wrong with not wanting a traditional lifestyle with kids, but maybe you should figure that out before you marry someone you're not happy with and, you know, have kids with that person.

- There's one particular anecdote about Nagel, that, if true, made my skin crawl – apparently he was chatting up a young lady at a party and proceeded to balance 2 full martini glasses on her cleavage. The author, of course, thinks this is both funny and charming – heck, the Nagel quote that Frankel chose for the book's introduction was "Martinis are like breasts. More than two is too many." Like, you couldn't have found a quote about Nagel's thoughts on art? Ugh.

- Frankel notes that Nagel would never accept anything less than what he perceived to be the "ideal" woman (and actually defends the artist): "To his few confidantes, Nagel related that he had no desire, no personal capability to be with anyone other than a 'perfect woman'. He openly – some would say cruelly – admitted that he could never stay with a woman who suffered any kind of debilitating disease, such as breast cancer. Like all men, Nagel had an idealized notion of what women meant to him which some might casually dismiss as objectification. In Nagel's case, however, it would be more accurately described as deification. To Patrick, women were divine and divinity tolerated no imperfection" (p.100). LOL, nope.

- Frankel also notes that there are "no women, living or dead" who mentioned Nagel sexually harassed them (p. 96). Throughout the book Frankel relentlessly points out that Nagel was, by all accounts, very courteous and professional. So great. Just because no one has come forward doesn't mean Nagel didn't harass them, and even if he really wasn't a creep, why does the author insist on giving him a cookie for it?

2 Just to be clear, I have no issue with female nudity or expressions of women's sexuality…but I do take issue when rampant exploitation of women is involved, which is the case with Playboy.

3 Bornstein was painted in a particularly negative light in Nagel's biography. I'm not sure how much of it is true, but apparently he was quite the "womanizer" (read: sexual predator) and exceptionally money-hungry, the latter of which caused him to colossally mis-manage Nagel's work after his untimely death.

4 At the age of 38, Nagel died suddenly of a massive heart attack after participating in an "aerobics-thon" at a charity event for one of his models. The autopsy showed that Nagel had a congenital heart defect which was the official cause, but I'm guessing his attempt at exercise after shunning it for his entire life may have been a trigger.

5 Frankel peppered Nagel's biography with remarks that were not exactly women-friendly, so I'm really trying not to agree with his point of view on Nagel's women. Frankly, both he and Nagel come off as tremendous douches. Among Frankel's greatest hits: "Party girls are not known for their financial acumen" (p. 108) – um, ever hear of Paris Hilton or the Kardashians? These "party girls" know exactly what they're doing when it comes to business; people who don't approve of Playboy are "prudes and shut-ins" (p. 244); and the last straw was Frankel's "where are they now" conclusion in which he gives a one-sentence follow up on those who figured prominently in Nagel's life. Surprise surprise, he saved what I'm assuming he thinks is the best for last: "Hugh Hefner is, was, and will forever be Hugh Hefner" (p. 279). Barf.

6 About the only useful thing in the biography were the last few chapters, which describe in detail the unraveling of Nagel's legacy due to both the greed of his manager and the fact that he did not have a will. There was a lot of legal and business jargon, but the gist is that Bornstein was chiefly responsible for the eventual devaluing and unlicensed reproductions of Nagel's work. This was aggravated by the lack of a will for Nagel, which most likely would have stipulated trademark and copyright guidelines – without those, it was essentially a free-for-all for anyone wanting to make money off his work. Things didn't go through the proper channels, and most of Nagel's art ended up being illegally reproduced.