"It never dawned on me not to do something because I was a woman…I thought nothing of approaching men like Vincent Bendix, the airplane manufacturer for whom the transcontinental air race was named, to explain my position: 'I can fly as well as any man entered in that race.' I didn't see it as being boastful so much as speaking the truth. I learned through hard work and hard living that if I didn't speak the truth about myself, no one else would fill in the missing pieces." – Jacqueline Cochran

As with Tommy Lewis and Richard Hudnut, I found a very interesting piece of makeup history completely by chance. I was thinking how cool it would be to see some mid-century modern designers' work on makeup packaging, i.e. Alexander Girard, Charley Harper and Paul Rand. On a whim I typed in "Paul Rand makeup" into Google (I think I was under the impression that I could somehow will makeup packaging with his work into being if I just believed hard enough) and lo and behold, a bunch of ads he had designed for a brand called Jacqueline Cochran Cosmetics popped up. I had never heard of it so I searched for just Cochran's name…and was mighty confused by the results.

Jacqueline Cochran (1906?-1980) was a pioneer of aviation in the 20th century, a.k.a. an aviatrix (don't you just love that word?! So bad-ass!) A contemporary of Amelia Earhart, Cochran set world records for flying from the '30s through the '60s, including:

- The first woman to enter the famous Bendrix race in 1935, and the first to win in 1938

- The first woman to fly a bomber across the Atlantic in 1941

- The first woman civilian to earn the Distinguished Service Medal for serving as the director of the Women's Air Force Service Pilots (WASPs) and training women pilots in WWII

- The first woman to break the sound barrier in 1953

- The first living woman to be inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame in 1971

- Held more speed, distance and altitude records than any pilot in history at the time of her death.

Further along in my search I discovered that this amazing woman was, in fact, the same Jacqueline Cochran as the one behind the cosmetics line. While I don't wish to diminish her accomplishments as a pilot, obviously I'm more interested in telling the story of her makeup company. As we'll see, Cochran may never have gotten into flying if it wasn't for her interest in cosmetics.

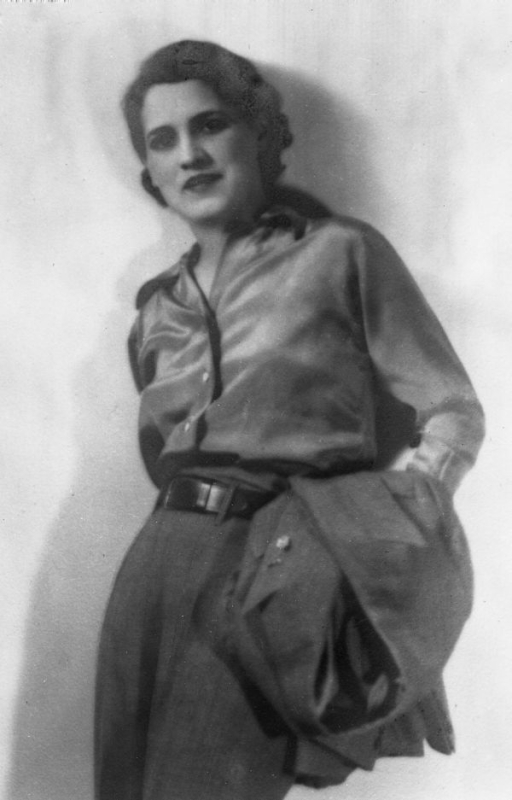

It seems like I'm sharing too much of Cochran's early life, but I promise it's relevant! Jackie Cochran (original name Bessie Lee Pittman1) was born an orphan around 1906 in Florida. The exact year is unknown because she didn't have a birth certificate. Adopted by an impoverished foster family, Cochran worked throughout basically her entire childhood. When I say "impoverished" I don't mean the family couldn't afford multiple cars; I mean they literally didn't know when or if their next meal would come, and the children's clothing consisted of flour sacks stitched together. In 1914 the family relocated to Columbus, Georgia to work at a cotton mill, children included. At the age of 14 she experienced her first foray into the beauty industry by taking on the role of "beauty operator" at a local salon, learning how to operate the perming machines and dyeing clients' hair. A traveling salesman for a perm machine knocked on the door one day and offered her a job as an operator in Montgomery, Alabama, and off she went. (I can't even imagine going to a strange town with not a penny in my pocket and knowing nearly zero people, especially at 15.) One of her regular customers suggested she go to nursing school despite the fact that Cochran only had a third-grade education. After deciding nursing wasn't the career for her, Cochran moved to New York and landed a job at Antoine's, a high-end salon located within Saks department store. I'm astonished at how hard Cochran had to work just to survive, and though sheer grit and fierce will to succeed, she was able to make a slightly better life for herself as a teenager than as a child. (You really need to read her autobiography, which is where I'm getting most of this information2 – the courage and determination she had were mind-blowing, yet she presents it in a very matter-of-fact manner, not in any sort of bragging or "woe is me" way. When a group of school girls asked why she was so ambitious, she straightforwardly replied, "poverty and hunger").

(image from floridamemory.com)

(image from floridamemory.com)

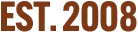

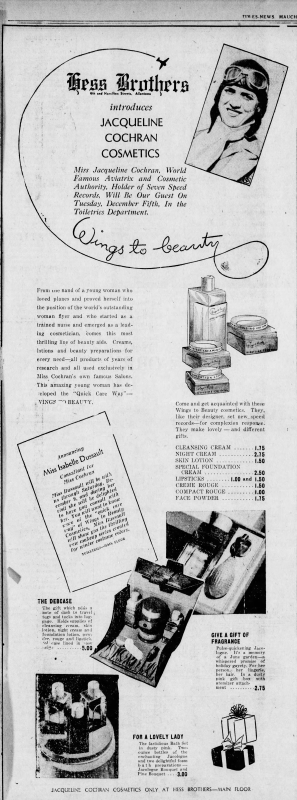

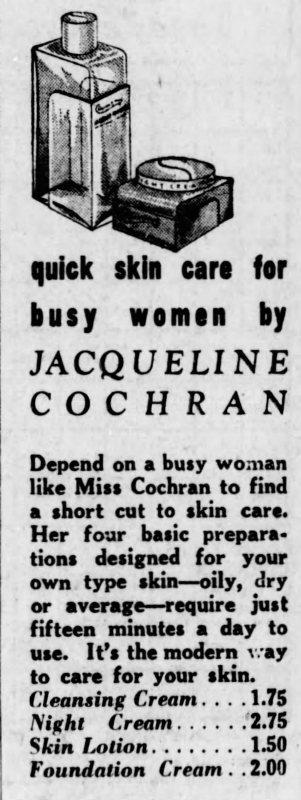

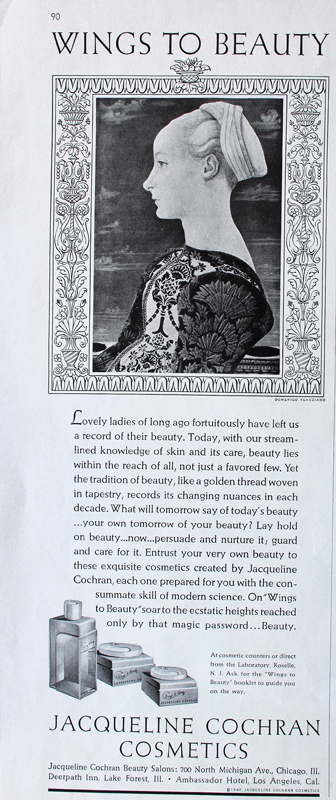

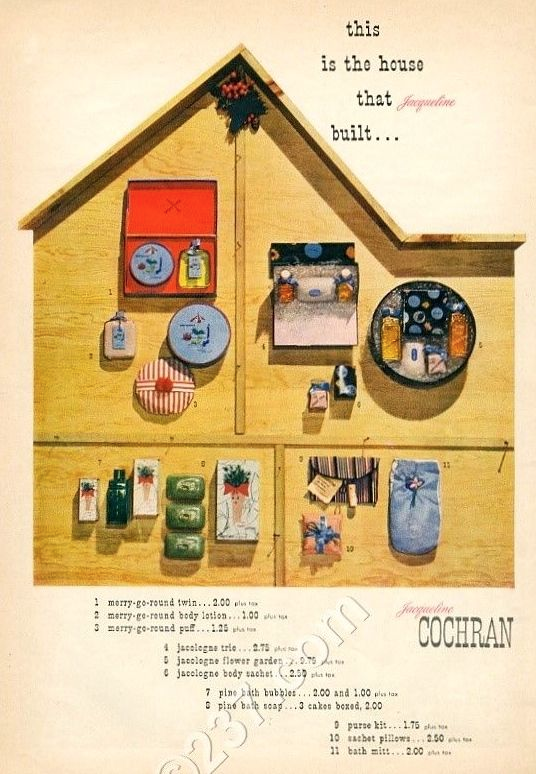

It was at a party in 1932 where she met her future husband, millionaire lawyer and businessman Floyd Odlum. Cochran was completely unaware of his background (and wealth) at the time, but was immediately attracted to him. The party's host introduced them, and during their chat, Cochran mentioned her desire to get out of the salon. "I've been thinking about leaving Antoine's to go on the road selling cosmetics for a manufacturer…the shop can be so confining and the customers so frustrating and what I really love to do is travel. I want to be out in the air." To which Odlum replied, "If you're going to cover the kind of territory you need to cover in order to make money in this kind of economic climate, you'll need wings. Get your pilot's license" (p. 57). And with that, Cochran took flying lessons and earned her pilot's license in a mere 3 weeks – setting records right from the start of her aviation career. In 1935 she officially established her eponymous line, which was meant for a more active woman who wanted to have adventures but also look polished while doing so. (Not that women need to look polished, or even require makeup to look polished, of course.) The brand's use of "wings to beauty" and claim that a full beauty routine takes just a few minutes a day suggest that it was a brand intended for the busy go-getter, perhaps even an early version of athleisure beauty. Indeed, both the ads and Cochran's own words in a 1938 interview demonstrate a no-nonsense, time-saving approach to beauty – ever practical, she skipped blush while flying. Says the article, "Mandarin fingernails and artificial eyelashes are ceiling zero to [Cochran]. 'You get pale at high altitudes,' she explains. So rouge just stands out in one big spot.' Likes an eye cream to 'keep my eyelids from drying'. There's a foundation cream with an oil base. 'Your skin gets dry in high altitudes.' Then lipstick and powder. That's all. In summer, she likes a grease make-up – foundation cream that makes you look all bright and shiny and is worn without any powder. 'Just a touch of paste rouge and your lipstick. It's young-looking and very attractive with sports clothes.'" I think Cochran definitely would be a fan of athleisure makeup today, as she seemed to prefer a minimal, fresh-faced look.

(image from hprints.com)

Some more of her musings on makeup: "I'm feminine but I can't say that I was ever a feminist…I refused to get out of the plane [after a crash in Bucharest] until I had removed my flying suit and used my cosmetics kit. That was feminine and it was natural for me. It gave me the pick-me-up I needed and I wasn't ashamed to do it. I didn't want to be a man. I just wanted to fly" (p. 20). Though she says otherwise, Cochran's actions most definitely paint a feminist picture. I'm seeing her reapplication of makeup following a crash as more of a coping technique and less "I need to look pretty". As we'll see, however, later advertising for the brand took a decidedly ageist turn.3

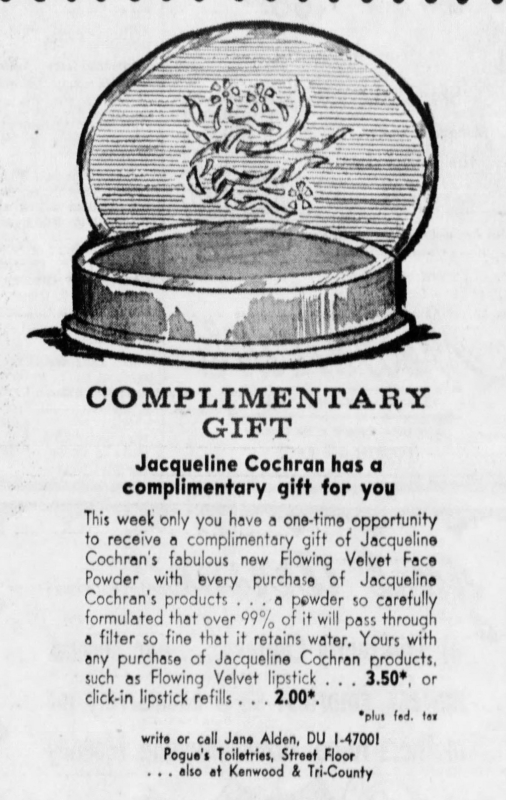

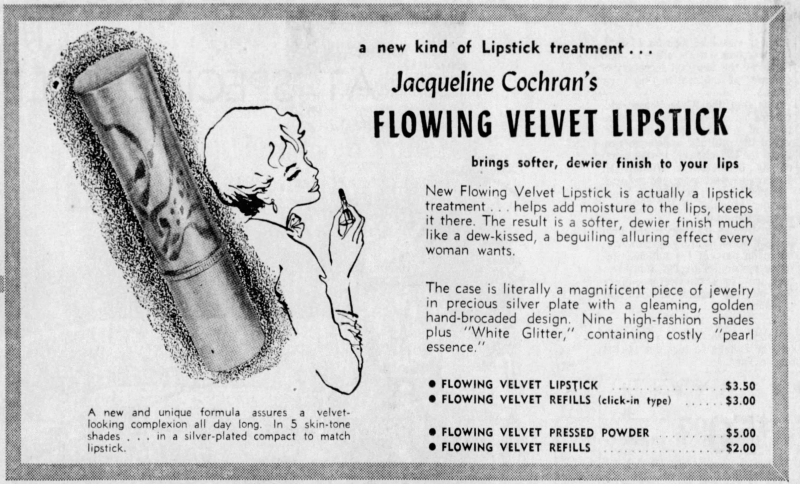

The brand was also a reflection of Cochran's unstoppable determination and desire to innovate. "I wanted no part of other people's products because I was crazy enough then to think I could do better…when I first set about to develop a greaseless night cream, I was told that a greaseless lubricant was clearly impossible. I knew they were wrong and I never recognized the word impossible. My most successful cream, Flowing Velvet, is the result of my stubbornness" (p. 119). Flowing Velvet was possibly the first moisturizer on the market intended to replenish the skin in high altitudes and extreme travel distances – i.e. long flights. It was introduced around 1942 and the line expanded in the '50s to include face powder and lipstick. Sadly, the advertising greatly contradicts Cochran's own words, as it seems to be geared towards ancient ladies over the age of 20 (!) trying to regain their youthful glow.

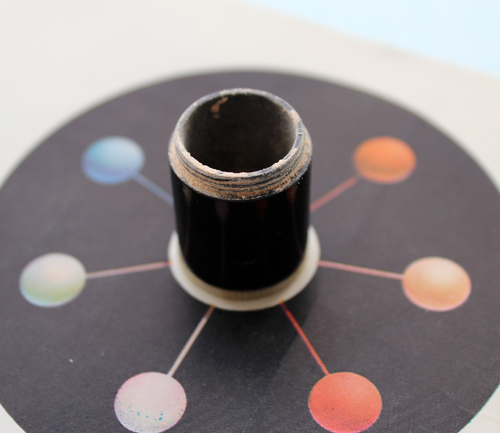

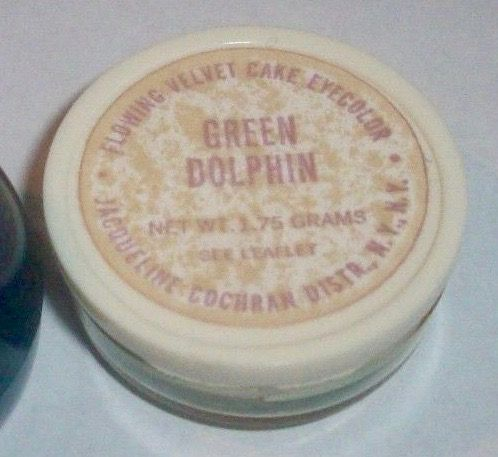

I couldn't locate a jar of the famous cream, but I did scrounge up a powder refill from the early '60s.

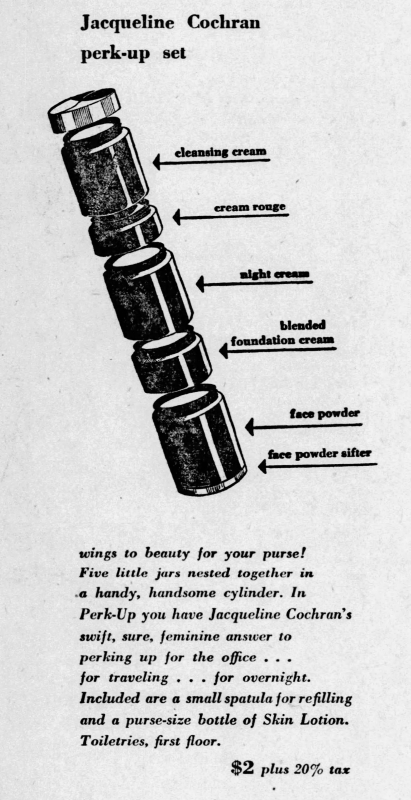

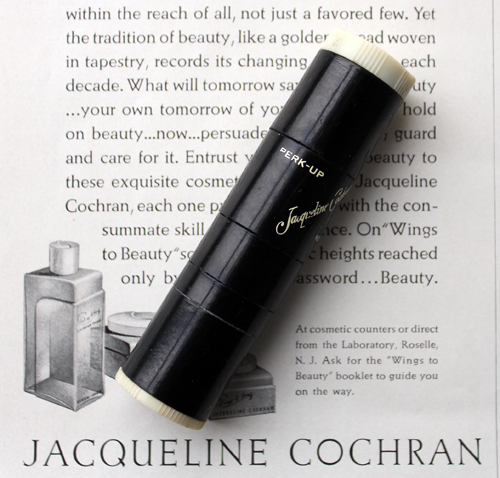

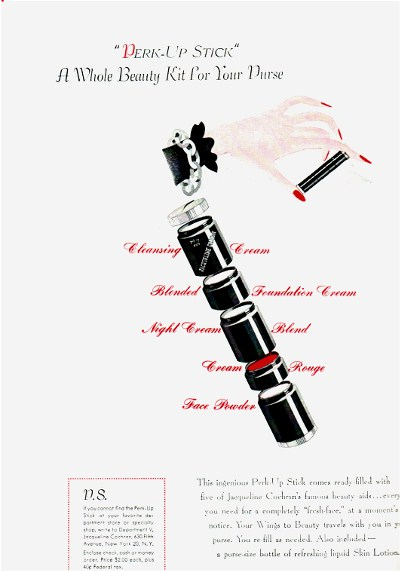

One of the most unique products Cochran came up with was the "perk-up stick", which contained 5 beauty products in a tiny cylinder for on-the-go usage. "I was proud of what we used to the Jacqueline Cochran 'Perk-Up' cylinder. I would take one on all my trips, on all my races. It was a three-and-a-half inch stick that came apart into five separate compartments for weekends or trips. It would fit anywhere and it had everything" (p. 119).

(image from Blue Velvet Vintage)

I was fortunate enough to snag one of these for the Museum.

I've taken most of it apart so you can see what it looks like. I couldn't get some of the compartments open and didn't want to break it, but all of the ones I did open still had product left.

At one point it had a sifter for the powder so that it didn't spill out when you opened the compartment.

The Perk-Up Stick also came with a little spatula so you could refill it as needed and hygienically apply everything. While the concept seems genius (seriously, why aren't companies now coming up with things like this?!) one must remember that products in the first half of the 20th century were generally smaller and more streamlined – no big huge honkin' palettes back then. And refillable packaging was way more common. In thinking about the lovely compacts I've collected over the years, I'm remembering that people didn't throw them out, they just popped in a refill. Still, the Perk-Up stick is unlike anything I've seen, contemporary or vintage. As the author of Blue Velvet Vintage notes, the closest thing we have today to the Perk-Up Stick are stackable jars.

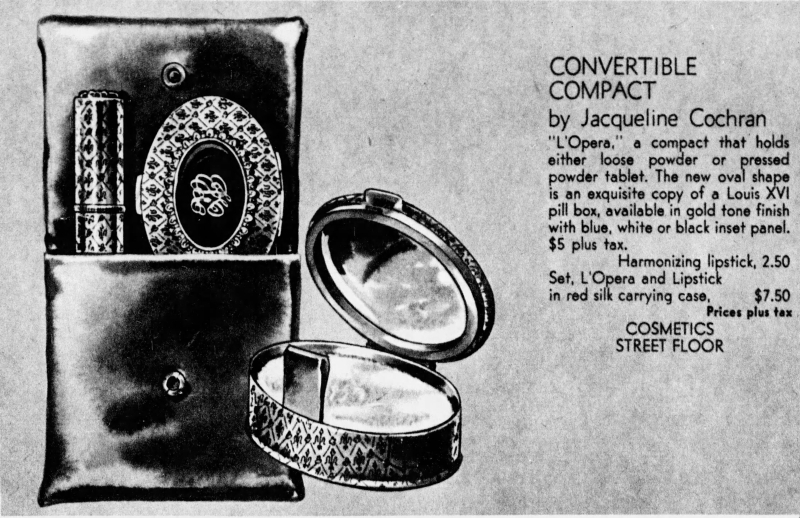

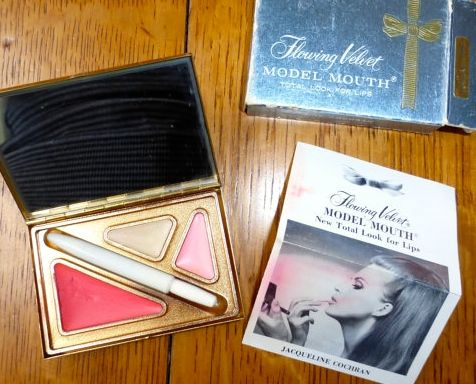

I also purchased one more piece from the early '60s. However, the photo below is not mine, for you see, I bought not one but TWO of these compacts, yet ended up with none. I bought one in late February, only for USPS to claim it had been delivered when it had not…and then a few weeks later when it still didn't resurface, I found another floating around on Ebay and bought it to replace the lost one. Despite being from a totally different seller in a completely different part of the country, somehow USPS lost the replacement as well. How they managed to do that I have no idea – perhaps this compact is cursed. There are others available for sale but they're not in as good condition as the ones I purchased, and at this point I'm not willing to invest any more money into it. Nevertheless it would have been a nice piece to have in the collection.

(image from pinterest)

(image from pinterest)

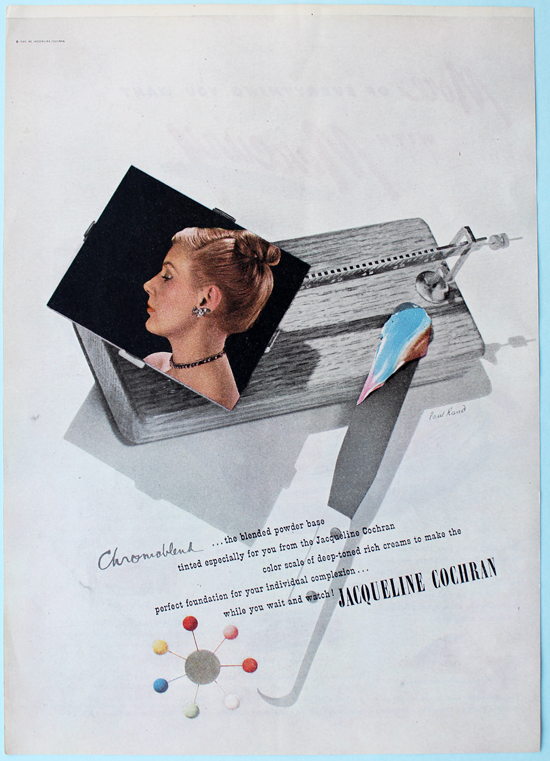

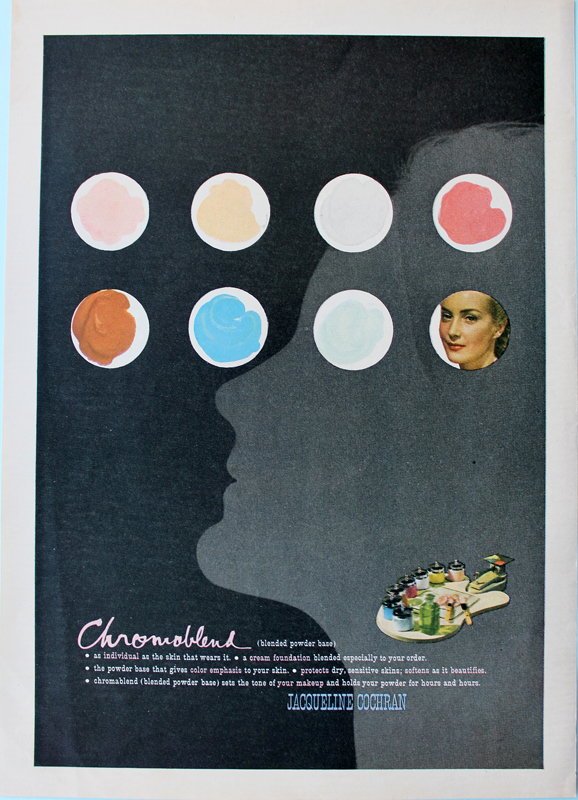

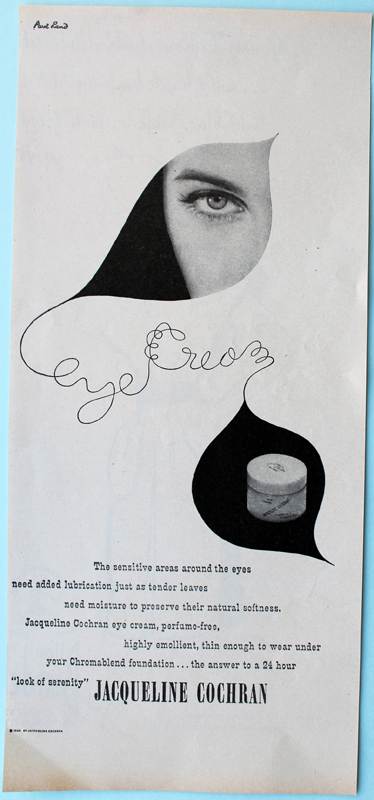

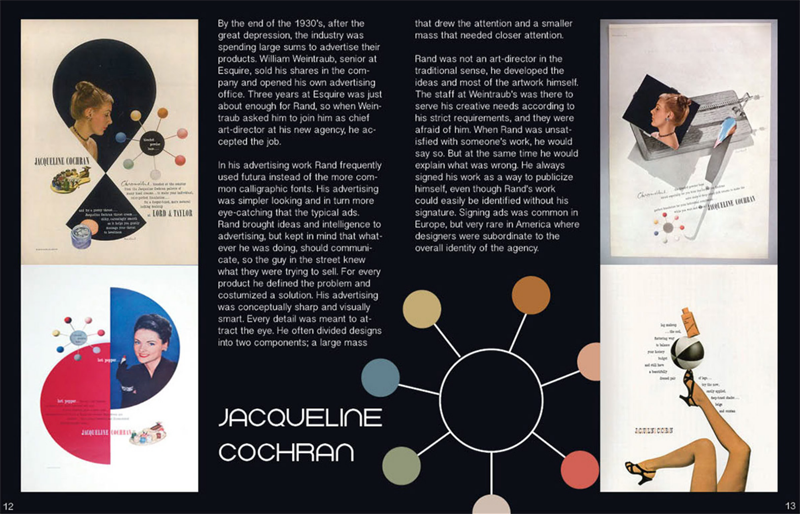

As for the Paul Rand ads, despite reading almost as much as I could find on Cochran, I'm still not clear on how the partnership with Rand started. I do know that I'm in love with the ads.

As this exhibition catalogue shows, I'm missing a few more of his ads, alas.

(image from amulhall015.portfolio.com)

(image from amulhall015.portfolio.com)

(image from pinterest)

(image from pinterest)

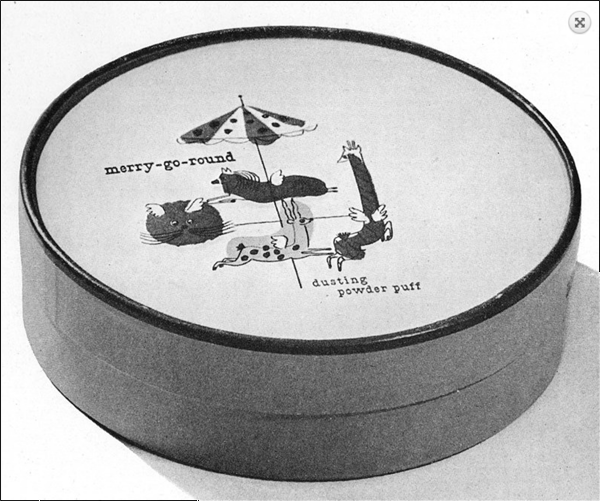

Obviously I'd give my eye teeth for this crazy powder!

(images from paul-rand.com)

(images from paul-rand.com)

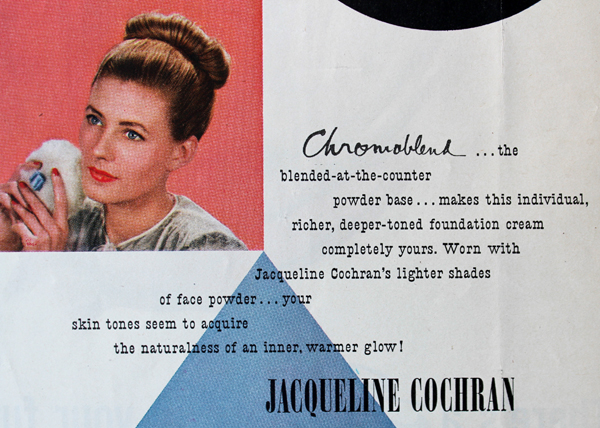

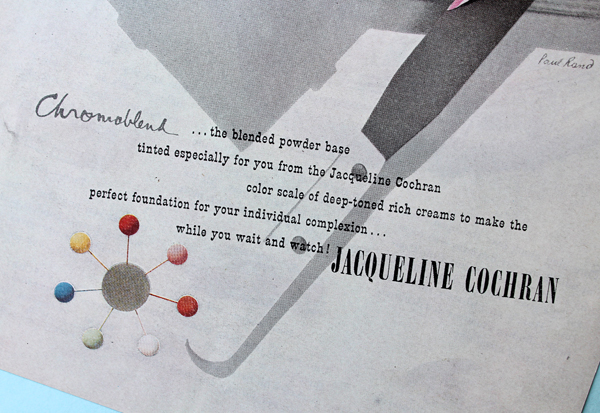

One observation I had in looking at these was that as heavily as the Chromoblend powder was marketed throughout the '40s – given the abundance of ads I'm imagining this was one of the pillars of the line in addition to Flowing Velvet – I couldn't find any jars to actually buy. I'm wondering if custom blend face powder king Charles of the Ritz was too stiff a competition. Did Cochran launch her own custom face powder as a way of thumbing her nose at his company and trying to prove that, once and for all, her product was superior? While it's unclear which Charles she was referring to, Cochran recalls her meeting with him less than fondly. "What an irritating snob of a man Mr. Charles was. I made the interview worse by insisting outright that I was an expert at everything. He didn't believe me. I didn't look old enough to be expert at anything, he said. We were two big egos out to prove who is bigger, better. In fact, I told Charles of the Ritz that not only was I good, I was probably better than he was. That amused him for a minute, but he was not so amused when I wanted fifty percent commission on every customer I had in his salon…it makes me smile to think that the cosmetics company I would found several years later, Jacqueline Cochran Cosmetics, still competes with Charles of the Ritz" (p. 55).

The overall concept of going to a counter and having custom face powder blended is remarkably similar.

The use of the spatula in this ad and the idea of making custom powder "while you wait and watch" is also nearly identical to Charles of the Ritz's ads.

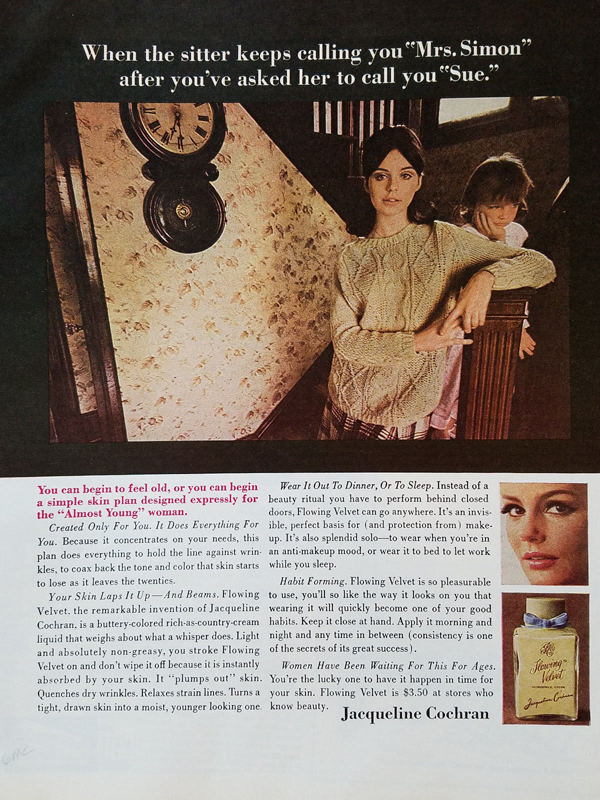

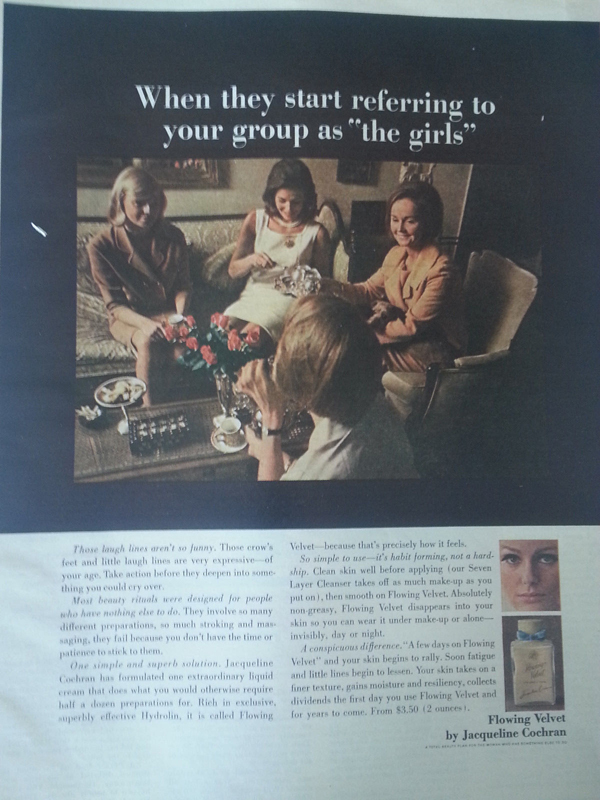

So what happened to Jacqueline Cochran Cosmetics after its heyday in the '40s and '50s? Cochran sold the company in 1963 to American Cyanamid Co. It was then formally acquired by Shulton, a subsidiary of American Cyanamid, in 1965. Unfortunately the ageism continued to run rampant in ads throughout the '60s.

At least they were still touting a speedy beauty routine for women who don't have much time to devote to skincare. Then again, sitting around and drinking tea doesn't exactly scream "busy". Like, they couldn't have shown a woman on her way to work or engaged in a sport of some kind?

(images from ebay)

(images from ebay)

But making women terrified of aging must have been effective, since the Flowing Velvet line was popular enough to continue expanding to include eye makeup and lip gloss.

(image from pinterest)

(image from pinterest)

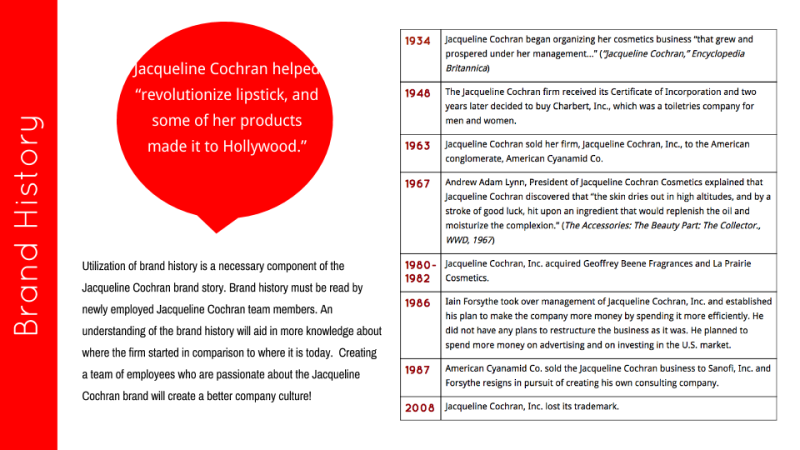

Unfortunately I'm not really sure of the brand's trajectory after the '60s. The timeline below suggests that Jacqueline Cochran Cosmetics is long gone, but also was part of a recent re-branding effort. So maybe there are plans to revive the line?

(image from behance.net)

(image from behance.net)

In any case, while the later advertising left something to be desired, you had to give Cochran credit for setting world flying records while simultaneously managing a multi-million dollar cosmetics company that at one point had over 700 employees. She also made good on the originally intended purpose of her pilot's license: after the war ended, Cochran flew an average of 90,000 miles a year to sell her line in various locales. For Cochran, the beauty industry allowed her to both get out of poverty and provide women with a sense of well-being (ageist advertising aside). "In a beauty shop the customers always came in looking for a lift. And unless I really screwed up, they left with that lift. I could give them that. I could give them hope along with a new hairdo. My skills as a beautician had bought me a one-way ticket out of poverty, and I'd never forgotten it. I was always proud of my profession" (pp. 46 and 57).

Had you ever heard of Jacqueline Cochran? What do you think of her and her line? It was pretty eye-opening for me – I think I should Google the other mid-century artists I mentioned and see what rabbit holes I can fall into. 🙂

1 Interestingly, Cochran's autobiography completely leaves out how her got her surname. Apparently she married Robert Cochran in 1920 at the age of 14, had a son a year later (who died at the age of 4 in 1925), and divorced Cochran in 1927. She selected the name Jacqueline on a whim while working at Antoine's. In the book there is no mention of her first husband; instead, she claims she chose the name from a phone book. "I went to the first phone book I could find, ran my finger down a list of names, and decided on Cochran. It had the right ring to it. It sounded like me. My foster family's name wasn't really mine anyway…I wanted to break from them in name. I had my own life, a new one. What better way to begin than with my own name. Cochran. Why the hell not?" (p. 49)

2 In addition to the staggering amount of information online, there are also several official biographies of Cochran. I chose the autobiography because I wanted to hear her story in her own words and get a sense of her personality.

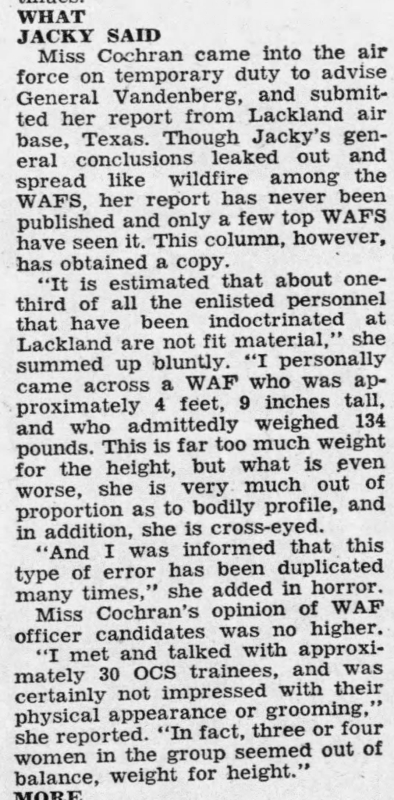

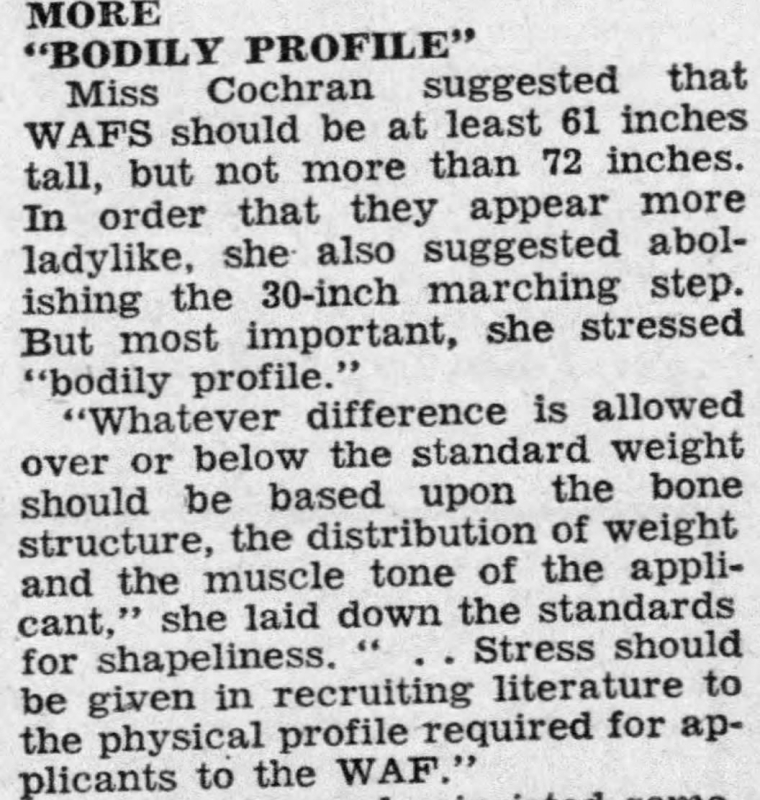

3 It seems highly unlikely that Cochran was directing the ad copy for her line, so I can't fault her too much for that, as distasteful as it is. However, a bit of gossip that appeared in a 1951 newspaper article makes me think that Cochran wasn't the feminist hero we'd like her to be. I've included a few excerpts in which Cochran basically says "no fatties allowed" in the Air Force's women's pilot program. Yikes.