I was compiling trivia focused on the topic of makeup-fashion collabs to put on Instagram a little while ago, and as with artist collabs, I quickly saw just how few were with Black designers. Even worse is that I realized the Museum was missing one of the two official collabs with Black designers there have been (which, again, like artist collabs is unacceptable and needs to change.) Estée Lauder teamed up with Nigerian-born, London-based designer Duro Olowu in the summer 2019, which coincided with the tremendous grief I was experiencing as a result of my dad's stroke earlier that year and the loss of my parents' home that August. Needless to say the collection slipped by my radar. Fortunately I was able to track down 2 of the 4 pieces and I hope I find the rest eventually.

I was compiling trivia focused on the topic of makeup-fashion collabs to put on Instagram a little while ago, and as with artist collabs, I quickly saw just how few were with Black designers. Even worse is that I realized the Museum was missing one of the two official collabs with Black designers there have been (which, again, like artist collabs is unacceptable and needs to change.) Estée Lauder teamed up with Nigerian-born, London-based designer Duro Olowu in the summer 2019, which coincided with the tremendous grief I was experiencing as a result of my dad's stroke earlier that year and the loss of my parents' home that August. Needless to say the collection slipped by my radar. Fortunately I was able to track down 2 of the 4 pieces and I hope I find the rest eventually.

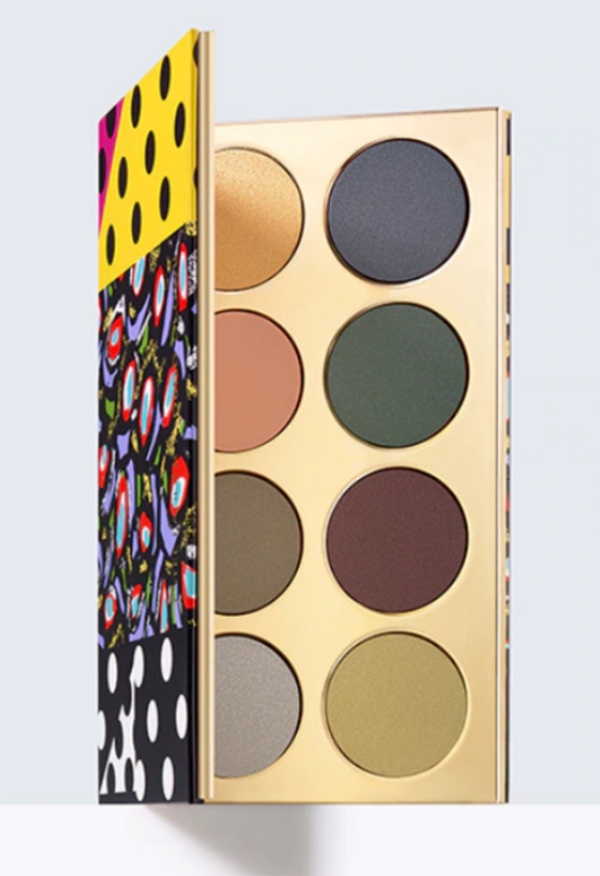

The collection consisted of two palettes (one for more casual daytime wear and the other for evening), and two lipsticks in neutral and red shades. Two makeup looks were modeled by Anok Yai, a Cairo-born model of Sudanese descent. She became the face of Estée Lauder in 2018 and is, in her own words, "obsessed with makeup".

The packaging borrows prints from Olowu's fall 2016 and 2017 collections. Anok also modeled a dress made by Olowu for the collab.

(images from vogue.com)

(images from vogue.com)

According to Essence, Olowu had always been a fan of Estée Lauder and was thrilled when they approached him to collaborate. Originally he was responsible only for the packaging, but that quickly shifted to choosing the makeup shades as well. Olowu wanted to create something for everyone. "If you’re a man, you really can’t quite imagine what it takes to decide on the right shade for your skin, especially in this world we live in with women of different ages, ethnicities and skin shades. I really thought long and hard about that and tried to bring that into the mix. It was a really great learning experience for me," he says. Olowu infused the collection with his signature ability to harmonize seemingly disparate themes. "My aesthetic is about mixing things that wouldn't normally be mixed together," he told British Vogue. "The idea is that the woman who wears this makeup looks like herself, but also who she wants to be. She's worldly, cosmopolitan and international. The collection is representative of all types of beauty – it's a global approach. That's what we wanted to create."

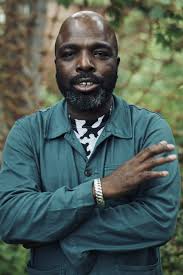

So who is Duro Olowu? Born in Lagos to a Jamaican mother and Nigerian father who had met and lived in England previously, Olowu was used to spending the summers there to see his mother's family and visiting Geneva for his father's business trips. Olowu attended school in England as a teenager and earned a law degree from the University of Kent at Canterbury before making the switch to fashion design. With this background, it's no wonder a he arrived at his trademark cosmopolitan aesthetic. The designer explains: "I would spend my time browsing in the Kings Road, Kensington Market and Hyper Hyper and going to clubs like the Wag, the Mud Club and warehouse parties. I managed to do very creative things in an important period of style and music in London, and I wanted to experience all the aspects of that time. From New Romantics to Leigh Bowery, punk and reggae, all mixed in. I read up on fashion from Vionnet and Saint Laurent to Fiorucci and knew all about that…I was particularly inspired by certain designers when I was young. Yves Saint Laurent, Stephen Burrows, Azzedine Alaïa, Madame Grès, and Walter Albini and Issey Miyake. My mother wore Rive Gauche when I was growing up, often mixing it with pieces of traditional Nigerian clothing and other pieces picked up on holidays abroad. I felt that these designers bought so many very different elements of culture and style into the realm of their work. The beauty of women was very inspiring to me, as were my parents, who loved clothes."

(image from vogue.com)

In 2004 Olowu launched his own label with a single dress that mixed pieces of vintage couture fabrics and new ones with his own prints on a loose-fitting, Empire-waisted silhouette. The "Duro dress," as it came to be known, was an instant hit among both fashionistas and critics and put Olowu on the international fashion map. Soon the designer was dressing the likes of powerful women such as Michelle Obama. "I'm just amazed by how women can do so much regardless of natural or imposed obstacles, and I feel that it's my duty to make sure they look good and feel comfortable doing it…whether I'm initially inspired by Eileen Gray, Miriam Makeba, Pauline Black, or Amrita Sher-Gil, I always end up designing for women of all ages and ethnicities, women whose way of life and work I respect. Then I hope that the clothes I've come to, with them as inspiration, would be of interest to them…I want to make women feel confident in an effortless way," he says.

(image from cnn.com)

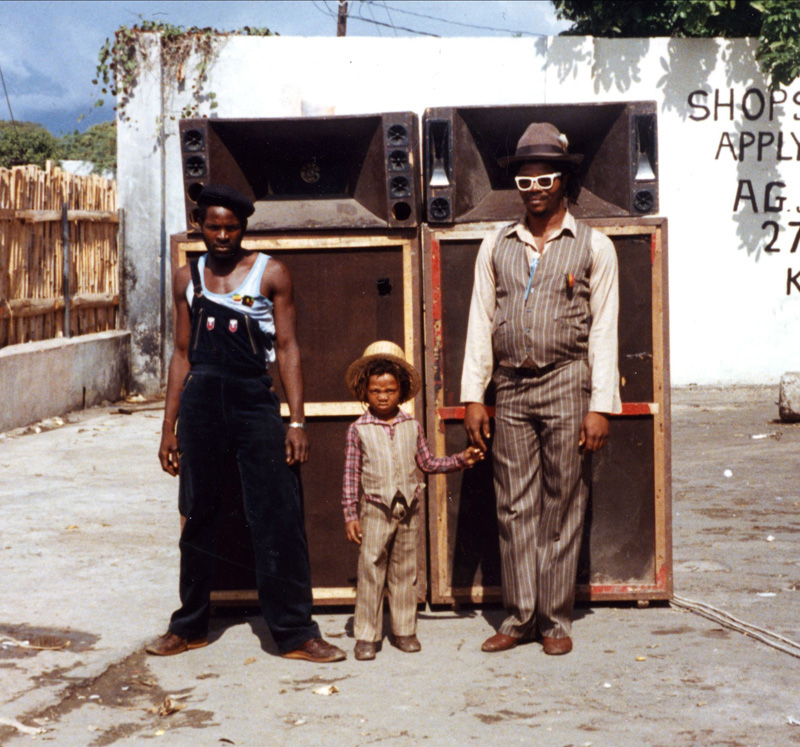

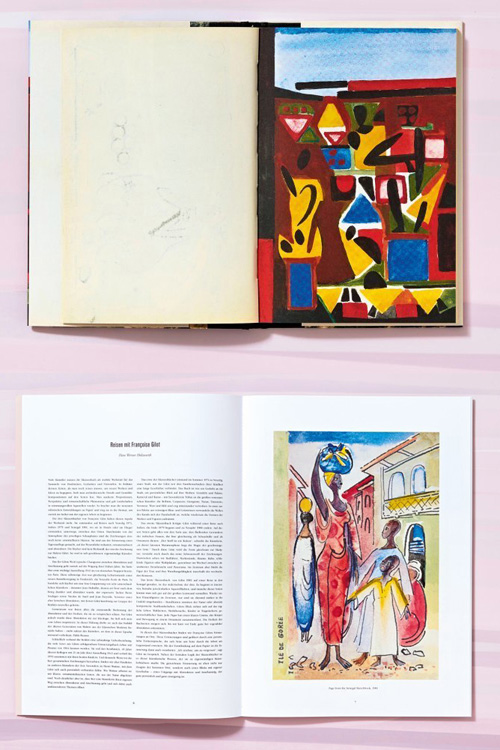

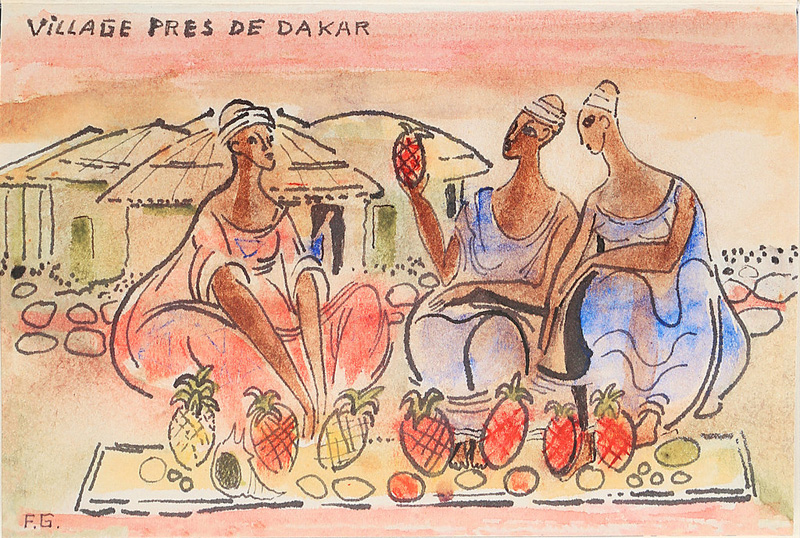

Says fashion writer Chioma Nnadi, Olowu's art history knowledge is "astonishing", and it informs his designs along with his personal background. "My prints are inspired by my Nigerian, Jamaican, and British backgrounds, as well as my love of art. Over the years, I have developed a curatorial and enthusiastic knowledge of historic and contemporary fabrics and textiles from all over the world. The mixing and draping of printed fabrics and textiles is something I have been exposed to all my life in the places I have lived or on my travels. It has been a signature of my womenswear collections from the very beginning and remains an integral part of my work. Fabrics always tell a story, and, when mixed well, exude the kind of joie de vivre and allure I am constantly inspired by…The color palettes of my prints are often by inspired art and artists, including Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Henri Matisse, Alma Thomas, Robert Rauschenberg, Alice Neel, Chris Ofili, Édouard Vuillard, El Anatsui, Lee Krasner and Toyin Ojih Odutola." I can absolutely see these influences in his color schemes, but what's even more impressive is how Olowu imbues his collections with the spirits of his current muses without directly referencing them and creates a whole new aesthetic in the process. For example, for his spring 2020 collection he was inspired by photographer Beth Lesser's images of Jamaican dancehalls in the '80s as well as sketches by Picasso's lover Francoise Gilot. As Nnadi points out, the former can be seen in the wide leg pants and some of the dresses' ruffled hems, while Gilot's are embodied by the drapey, flowing silhouettes and softer floral prints. I'm blown away by how Olowu combines and reinterprets the vibes of these two totally different bodies of work while also adding his own style to the mix.

(images from vogue.com)

(images from vogue.com)

(images from lostinburanism.tumblr.com and timeline.com)

(images from lostinburanism.tumblr.com and timeline.com)

(image from caughtbytheriver.net)

(images from vogue.com)

(images from vogue.com)

(images from taschen.com)

(image from nytimes.com)

(image from nytimes.com)

While his clothing is wonderful, it's Olowu's curatorial experience I find most extraordinary. In 2008 Olowu married Thelma Golden, Director and Chief Curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, which further intensified his appreciation of art across all mediums. He curated his first exhibition in 2012 at New York's Salon 94 Freemans, followed by two more in 2014 and 2016. All were so well-received by the public and critics alike that the exhibition catalogs had to be reprinted after repeatedly selling out. Olowu's most recent exhibition, Seeing Chicago, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) is one of the most innovative and unique curatorial endeavors I have ever laid eyes on. Comprised of 367 (!) works from all different eras ranging from painting and photography to crafts and books, the pieces are arranged salon-style to enhance the dialogue between them. Olowu's love for Chicago grew out of his long-term partnership with the boutique Ikram. "I first came here because I've been working with Ikram, a fantastic store, for about 16 years…I was just amazed at the unique nature of the Chicago mindset. They're not followers; they do their own thing, and they're very proud of what is within their city, without showing off. And in that way I felt that sometimes you overlook actually what is there and how amazing it is." From there he gathered objects he felt best represented the diversity and character of the city. "I wanted to show old school, curious collecting from the '60s, '70s, and '80s, along with community and philanthropic collecting, in a forward-thinking way," Olowu tells CR Fashion Book. "It was intuitive how it came together—the variety of having Matisse, Louise Bourgeois, and Glenn Ligon in the same space with Rashid Johnson, Martin Puryear, and Lorna Simpson. I did not purposefully seek any of the art—the artwork itself called me." I love the idea of art or objects "calling" – it happens to me when organizing the Museum's exhibitions, although sometimes I'm driven by certain words or phrases that just keep sticking in my head.

Instead of arranging artwork into neat categories, Olowu takes an unexpected and refreshing approach that still makes sense thematically. Explains MCA (soon to be Guggenheim) curator Naomi Beckwith, "I don't think we realize that when we go to museums, oftentimes the work that we see in one specific gallery or in one show is usually like for like. That is to say that all the works in African sculpture are in the African galleries. All the works by French painters of the late 19th century are in another gallery by themselves. All the pottery from Asia is either in the Asian gallery or in the decorative arts gallery. We began to separate things out in ways that feel logical, but what it doesn't often allow is for things across cultures to speak to each other, or things across time periods to live with each other. Duro kind of ignored those basic art historical claims and just asked us to realize the affinities that art may have, across the country, across the world, across time."

The colors of the walls and pedestals reflect the color palette used by Amanda Williams in her iconic Color(ed) Theory series, in which she painted structures slated for demolition in Chicago's Englewood neighborhood and named each to represent an aspect of Black consumer culture. By using these colors for the exhibition decor, Olowu connects the objects both to each other and to Chicago's history.

"Both as a fashion designer and as a curator, [Duro is] interested in bringing cultures and cultural objects together in an exchange and in a conversation that allows things to speak to each other in an equal plain, without hierarchy, without a sense that one thing is superior to another, or better than another, or that one culture, one geography, one place or one history should supersede another," continues Beckwith. "And really the question for his practice is, how do we allow all this to live together, in a kind of egalitarian beauty? And you'll see that happening in the exhibition." This is a far less elitist approach to curation that we typically don't see in major art museums. Underscoring this more democratic methodology was the display of outsider art alongside canonical names like Kerry James Marshall and Jean Arp. "He’s not making big distinctions between self-taught and academically trained artists. He’s looking at furniture as much as sculpture, at craft as much as painting. We're at a moment in art history when we're seeing deep dissatisfaction with the standard narratives," notes Beckwith.

The last room presents a group of mannequins observing the art, meant as stand-ins of fellow museum visitors. While they're dressed in Olowu's designs, they're intended to emphasize his community-minded approach towards art and curation. "They are looking at the art, and at you…there is a relationship between the eye and the heart, outside of genres and contexts. One of the joys of art is that it can bring people together—through diversity and unification, all divisions are gone," he says.

(images from crfashionbook.com)

(images from crfashionbook.com)

In short, Duro Olowu was meant to be a curator, more so than a fashion designer, and I hope he pursues curation full-time. I love his clothes, but I find his exhibitions even more inspiring. My spirits are also buoyed up by the fact that his shows have been generally well-received without him having any formal curatorial training. I would dearly love to have him curate an exhibition for the Museum, although since he doesn't consider fashion to be art, he probably wouldn't consider makeup worthy of curation either. Plus, his style may be very difficult to translate to cosmetics. As Jessica Baran points out in Art Forum, Olowu's aesthetic can veer into commercial territory. "[At] its worst the display method mirrored the style of luxe domestic decor and retail store design (in fact, Olowu’s first curatorial endeavors were seen as extensions of his London boutique, which is organized similarly). Full of surface seductions 'Duro Olowu: Seeing Chicago' masked with its immersive pleasure its myriad contradictions, many of which are mirrored by fashion itself: a global industry blinkered by its own excesses, situated somewhere between haute merch and popular necessity, expressive art and practical consumability." You know I despise any museums in which makeup is presented as something to buy rather than appreciate – it's something I've been even more mindful of since I interviewed an exhibition designer so many years ago – but I think I could channel Olowu's vision and put together a broadly focused show in his style that celebrates the diversity of makeup and its history without it seeming like retail. The ideas are flying fast and furious now so I better go so I can jot them down. 😉

What do you think of the Estée Lauder collection and Olowu's fashion/curation?